Chapter 1

Introduction to geriatric emergency medicine

Demographics

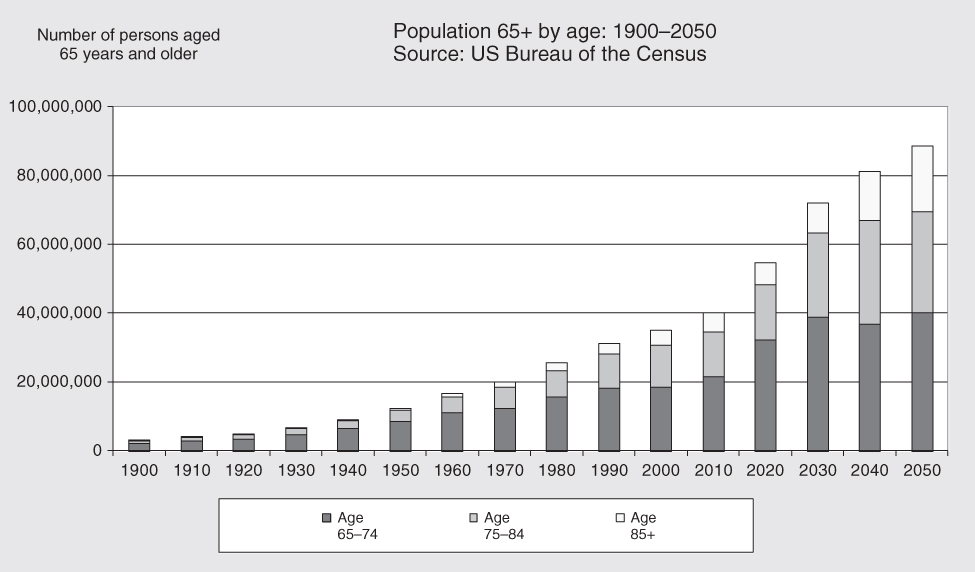

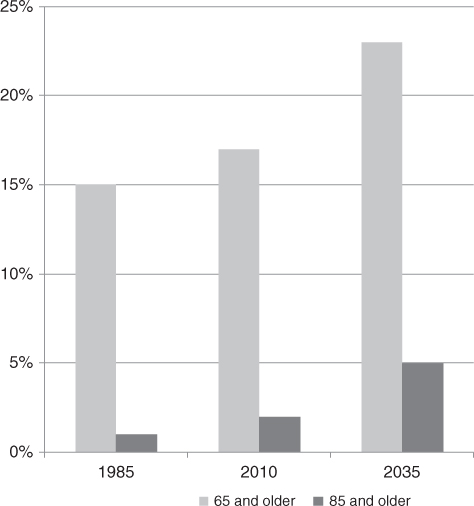

Population ageing is an international phenomenon, in terms of both the increasing number of people reaching old age and the rise in median age. Between 2000 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years of age will double from about 11% to 22%, with the absolute number of people aged over 60 years expected to increase from 605 million to 2 billion over the same period (1). The number of people aged 80 years or older will have almost quadrupled to 395 million between 2000 and 2050 (1) (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). An ageing population brings potential benefits but also imposes particular challenges, particularly a growing demand for health and social care services. Whilst many people are staying healthy and active into old age, the number of older people who are reliant on care or have multiple health problems is increasing.

Figure 1.1 Projections of the population by age and sex for the United States: 2010–2050 (NP2008-T12), Population Division, US Census Bureau; Release Date: August 14, 2008.

Figure 1.2 Percentage of older people in the United Kingdom 1985, 2010, 2035.

Source: Office for National Statistics, National Records of Scotland, Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.

Over 65% of patients admitted to hospital are over 65 years old in the United Kingdom (UK) and many have complex medical conditions (2). In the United States (US), 19.6 million emergency department visits were made by patients aged over 65 in 2009–2010 (3). Those aged 65 years and older are twice as likely to be admitted than those under 65, rising to over 10 times more likely in those aged 85 and above (4).

Emergency department attendance as an older patient is associated with adverse outcomes, including an increased rate of subsequent (separate) hospitalisation, increased re-attendance to the ED, increased rate of functional decline and reduced capacity for independent living (5).

Emergency presentations

Illnesses in the older patient presenting to the ED are more likely to be of a higher acuity compared to younger patients. They are more likely to arrive by ambulance, they are more likely to be acutely unwell even when they appear stable on initial evaluation, and they are more likely to require immediate critical care.

Older patients often present with non-specific problems including the classic ‘geriatric giants’: falls, delirium, immobility and incontinence. These presenting complaints are often representative of multi-factorial disorders including underlying illness and comorbidity that require consideration of a broad differential; the assessment of these older patients requires skilful history and examination.

Frailty at the front door

The presentation of frail patients to the ED and acute medical unit (AMU) is attracting increasing interest. These patients have previously not been a priority and have fallen through gaps in an environment designed to treat condition-specific problems rather than address the more complex issues which can present in a patient who is ‘frail’. Mortality rates of frail older patients presenting to EDs and AMUs is high and as such, this condition must be addressed by emergency physicians and acute physicians.

A large study on frail adults who were discharged from the ED showed they have a poorer 30-day outcome that non-frail patients, with between 10% and 45% (depending on level of frailty) increased risk of hospitalisation, nursing home admission and death (6). Studies such as these make the recognition and diagnosis of frailty early in an acute illness episode imperative so that interventions can be planned and initiated.

A recent international consensus on the definition of physical frailty defines it as, ‘a medical syndrome with multiple causes and contributors that is characterised by diminished strength, endurance, and reduced physiologic function that increases an individual’s vulnerability to increased dependency and/or death’ (7).

The definitive diagnosis of frailty is usually made by a geriatrician and can be based on any number of well-validated models of frailty; two of the most well-known theoretical concepts of frailty are the frailty phenotype (Fried) (Box 1.1) and the frailty index (Rockwood).

In the ED or AMU setting, the frailty phenotype may be more appropriate as it can be applied at first contact; the frailty index is a deficit accumulation model that has many strengths but does require comprehensive medical and functional assessment before it can be applied.

There are several rapid screening tests that are aimed at helping acute care physicians to objectively identify frail patients early in their admission and target early interventions to help prevent deterioration in health or increased dependency (Table 1.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree