1 Introduction to Complementary Medicine in Oncology

1 Introduction to Complementary Medicine in Oncology

Introduction

Introduction

New developments of complementary medicine in oncology have emerged out of a general disappointment with the results of more traditional treatment options. Despite innovative approaches toward tumor destruction, including surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, cancer mortality rates have not been reduced in the United States or other industrialized countries in the past twenty years. The age-adjusted mortality rates have even increased by about 6 %. Notable treatment success has only been achieved in rare cancers (such as leukemia, lymphomas, and testicular carcinoma) (3).

Global analyses conducted independently by Abel (1) and Moss (16) dampened the optimism associated with chemotherapy for advanced carcinomas, especially when “responses” (temporary tumor shrinkages) are used as a measure of therapeutic success.

These authors urged the medical establishment to think about new therapeutic strategies. While conventional oncology still promoted the application of high-dose chemotherapy, which can only be survived through measures of intensive clinical care, some less toxic complementary approaches underwent scientific and clinical trials.

The effectiveness of high-dose chemotherapy of epithelial tumors (e. g., breast cancer) still remains to be proved (15). The use of chemotherapy for advanced tumors does not result in significant survival outcomes (1, 16). A statement made by the drug administration in Germany, about unconventional alternatives with respect to aggressive tumor treatment, should be mentioned: “The practice of drug therapy as the main pillar of treatment offered in medicine by all industrialized nations is based on the scientific acknowledgement of certain laws (drug-receptor interactions, dose-response relationships, demonstrated effects on the disturbed regulation of biochemical and psycho-physiological processes) and on the testing of these medicines according to internationally accepted clinical-pharmacological and biometric methods.” (7)

The consistent application of this statement should result in an ethical consensus and lead to the following set of requirements:

• Scientific study and evaluation (proof of efficacy) of all therapeutic concepts

• Limitation to diagnostics and therapeutics with proved efficacy and their inclusion into health insurance plans

• Development of a comprehensive plan for adequate prevention, prophylaxis, diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up of cancer

While the importance of tumor prevention has moved into the forefront of public consciousness, due to intense awareness campaigns by the cancer societies of various nations, the areas that include diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up need to catch up. Widespread passive follow-up ought to be replaced with an active treatment plan tailored to the respective indications of the patient’s disease. In order to reach this goal, oncologists should aim to expand on proved complementary medicinal approaches and optimize the timing of therapy. Particularly the induction of immune suppression (11, 13), the surgery-induced spread of metastases (10), as well as the impairment of quality of life (9, 13) due to the use of traditional therapies can be compensated by a timely combination with complementary medicinal approaches.

Overview of Methods

Overview of Methods

Complementary medicine should primarily be seen as an addition or enhancement of current standard treatment options in oncology. It is to be differentiated from “alternative medicine,” which seeks to find replacements for conventional toxic approaches. Although complementary and alternative medicines are grouped together in the popular acronym “CAM,” they are in fact quite different in their aims. Since many alternative treatments are still poorly documented, equating the two could lead to a misguided and undeserved rejection of all complementary medicine.

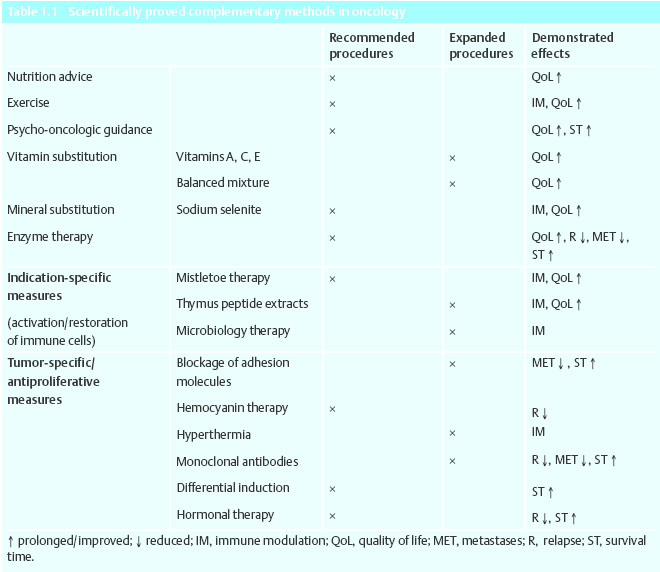

That many of the methods discussed in this book can complement standard treatment has been proved in clinical trials that have shown an increase in the quality of life, as well as in total survival time. Biometrically secured and prospectively randomized data are presented for these approaches, for the most part from placebo-controlled clinical trials and cohort trials according to Good Epidemiological Practice (GEP), which will be described shortly (Table 1.1).

Nutrition Advice

The National Cancer Institute of the United States attributes about 35 % of all types of cancer to malnutrition (5, 17). The potential for prevention of cancer is thus large, and general nutrition guidelines for primary and secondary prevention are of much value (according to the German Society of Nutrition [DGE] and the American Institute for Cancer Research).

Once cancer becomes apparent, success of therapy, or the healing process, is decisively determined by the patient’s nutritional state. Fundamentally, a specific advisory for the patient’s optimized nutrition is of great importance at this point, since malnutrition and cachexia can have a significant effect on the quality and duration of life. Malnutrition increases cancer mortality by about 30% (17), and cachexia worsens the prognosis of disease significantly, since it is associated with reduced response to treatment, more complications, and therefore prolonged hospitalization.

Exercise, Physical Activity

Focused gymnastics, moderate exercise (of longer duration), or physical activity has proved beneficial in the prevention and follow-up of cancer (2, 21). This has led to:

• Improvement in bodily functions, including regeneration of previous abilities (for example, restitution of shoulder-arm-joint mobility after cancer-destructive therapy for breast cancer).

• Activation/modulation of hormones and immune system responses and positive influence on mood, sensitivity to pain and quality of life through the release of neuropeptides (e.g., β-endorphins).

• Result in psychological stabilization through social contacts (sense of belonging to a team or group).

Psycho-Oncological Support

Psychotherapeutic measures should be an integral part of any immediate treatment or rehabilitation of today’s cancer patient. It is widely known that handicaps may lead to psychosomatic diseases and that these can be relieved or even cured with appropriate psychological aid or therapeutic modalities.

In addition, psychotherapeutic measures are indicated for dealing with disease in the following types of problems and symptoms:

• Emotional disturbances, such as fear and depression

• Conflicts within a relationship or family

• Impairment in social behavior

• Social withdrawal tendencies

• Psychological impairment with physical decline and deterioration

• Problems in accepting the disease

• Discrepancies between therapeutic expectancy and actual treatment options

• Inadequate behavior toward disease

Substitution of Essential Minerals and Vitamins

The cancer patient has an increased requirement for essential micronutrients that are rarely adequately supplied even through a wholesome and balanced diet. This especially holds true before or during tumor-destructive therapy, since the need for micronutrients in these phases is increased due to side effects such as reduced appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and perspiration.

It has been demonstrated that a deficit in micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) results in a reduced tolerance of current standard cancer therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree