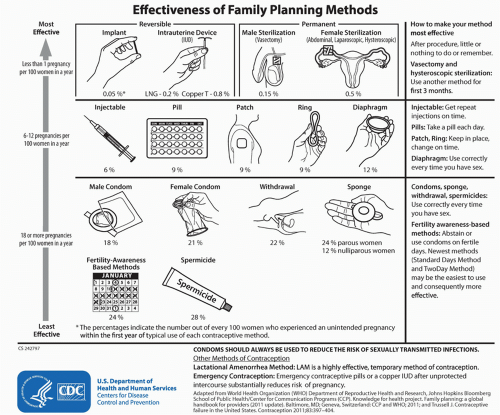

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) is an umbrella term for provider-inserted methods, which once placed provide superior protection against unintended pregnancy. LARCs, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and progestin contraceptive implants, have a major advantage over other birth control methods as they minimize problems with adherence and maximize continuation rates. Family planning experts have recommended LARCs as a first-line contraceptive for women of all ages, including adolescents and nulliparous young women, since 2007. However, LARCs continue to be an underutilized method of contraception despite a long history of efficacy, safety, and ease of use for women of all ages. Fewer than 1 in 10 young women less than 25 years of age take advantage of these easy-to-use, extremely effective methods. Providers, and patients, who wish to avoid early or unintended pregnancy, can benefit from improved counseling on the option of these LARC devices.

TYPES

Long-acting reversible contraception includes a variety of “set and forget” methods of contraception. These forgettable contraceptives are typically provider-inserted devices that last over many years, but, once removed, are quickly and completely reversible, offering women a flexible and responsive means of family planning. LARCs offer adolescents and younger women a means of contraception that is as effective as more permanent sterilization procedures, but keeps a young woman’s future reproductive options fully intact without sparing efficacy. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) women are at high risk for early and unintended pregnancy. Therefore, LARCs have been recommended as a top-tier method for teens since 2007.

1Because LARCs are functionally user independent, typical and perfect use failure rates are essentially the same, eliminating problems with adherence and misuse

(Fig. 44.1). Additionally, LARC users demonstrate consistently higher continuation rates than short-acting methods across all ages. At present, there are four Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved devices in the US, with many more options available internationally. Two FDA-approved IUDs include levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine system (LNG-IUD, Mirena, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, 2000) and CuT380A IUD (CU-IUD, Paragard, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, 1984). Both have been in use and well studied for over 20 years. In 2013, the FDA approved an additional LNG device, Skylar (Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals) onto the US market. The etonorgestrel (ENG) progesterone-only implant (formerly Implanon, now Nexplanon, Merck Pharmaceuticals) was FDA-approved in 2006, and is another inserted device that is placed in the subdermal tissues of the nondominant upper arm. All four methods can be safely used in teens and nulliparous young adults, and should be considered first-line options for young women wanting to avoid unintended pregnancy. While use of LARCs is increasing in the US, and in particular among younger women, providers miss opportunities for educating, counseling, and recommending these options as the most effective methods of contraception for AYA women.

2

MECHANISM

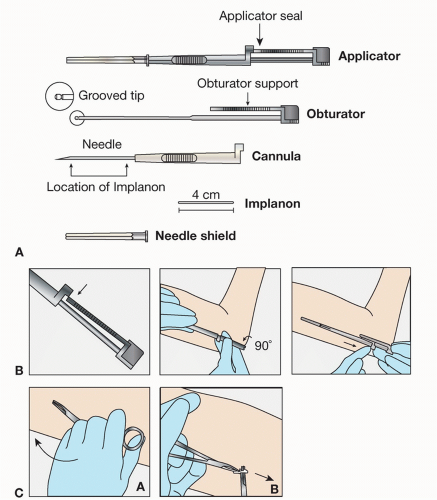

The ENG is a single 4 cm by 2 mm flexible ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer rod that is inserted subdermally

(Fig. 44.2). The newer ENG device, Nexplanon, has an improved inserter that limits the placement depth, and prevents deep or intramuscular insertions. Nexplanon contains 15 mg barium sulfate, making it radiopaque and easier to detect with x-ray, especially important for verifying location during the removal procedure. ENG’s active ingredient is 68 mg ENG, which is slowly released over 3 years. Peak serum ENG concentrations reach 800 pg/mL, with a gradual decrease to less than 200 pg/mL by year 3. As with other progesterone contraceptive methods, ENG inhibits ovulation, thickens cervical mucous, and thins the endometrial lining. Its overall pearl index is estimated at 0.38%, indicating a less than 1% failure rate.

3 While FDA approved its use for 3 years, there are indications that the ENG has demonstrated effectiveness (0 pregnancies) for up to 4 years.

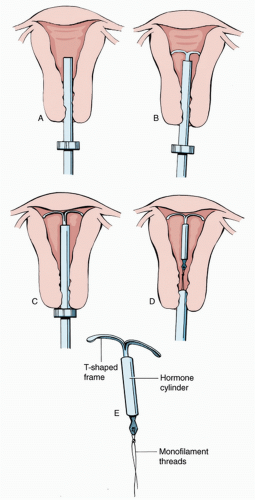

4 LN-IUDs are approved for 3 (Skylar) to 5 years (Mirena) of use

(Fig. 44.3). As with the ENG device, Mirena seems to have excellent efficacy for up to year seven. Similarly, the CU-IUD (Paragard) is approved for 10 years, but additional efficacy has been demonstrated up to 12 years or longer.

5IUDs are not abortifacients and do not interrupt an implanted pregnancy. IUDs do not work by suppressing endogenous estrogen and progesterone hormone production; thus, ovulation may continue. In general, IUDs are toxic to sperm and oocytes; gametes are rendered inactive or ineffective, and do not fertilize or form viable embryos.

6 CU-IUDS create an intrauterine sterile foreign body reaction with cytotoxic inflammatory mediators destroying sperm and ova, inhibiting motility, disconnecting head-tail, inhibiting acrosomal enzyme and capacitation, impairing penetration of the zona pellucida, and with increased local prostaglandin levels,

additionally impairing ova fertilizability. The LNG-IUD creates thick impenetrable mucous, a thin atrophic lining, inflammatory effects, and impaired tubal motility. The CU-IUD T-shaped polyethylene frame is wrapped in copper wire and contains barium sulfate in the stem to render it radiopaque. Copper ions act as a functional spermicide, which both renders gametes inactive and creates an environment unsuitable for fertilization. With a pearl index of 0.8 and estimated 100% efficacy as an emergency contraception (EC) method, CU-IUD is an extremely effective FDA-approved method of contraception for all ages.

6LNG, like its copper counterpart, is a nonsystemic hormonal method, creating a local intrauterine environment hostile to gametes and fertilization. The larger (32 mm × 32 mm) T-shaped polyethylene Mirena contains 52 mg LNG, which is slow released at a rate of 20 mg per day over 5 years, with an overall pearl index of 0.7%. By year 5, the daily progestin dose decreases by 50%, but the device has demonstrated effectiveness up to 7 years.

7 LNG is released directly into the uterine body for largely paracrine rather than systemic effects. Serum progestin levels are about half that of ENG implant users and one-tenth of oral LNG users.

8 The smaller (28 mm × 30 mm) Skylar IUD contains 13.5 mg LNG with a release rate of 14 µg/day and decline to 5 µg/day after 3 years. Ovulation may be suppressed in some women, but is not the main mechanism of action, with between 45% and 75% of women ovulating on the 52 mg device, and almost all women ovulating on the lower-dose LNG-IUD. Ovulation on the lower-dose LNG-IUD may result in less amenorrhea and more regular menses, which can be a desired effect for some women.

8These “set it and forget it,” long-acting, completely and immediately reversible forms of birth control offer patients improved adherence and greater likelihood of continuation over time, making LARC an ideal form of contraception for AYAs, and all-age women wishing to delay or prevent unwanted pregnancy and parenthood. The less than 1% failure rate for LARCs remains the same across both younger and older age groups, while women younger than age 21 years have twice the risk of contraceptive failure, as they use more short-acting methods compared to their older peers.

9 As the inherent characteristics of inserted methods

eliminate problems with misuse and adherence, method initiation and continuation become the critical elements in promoting their usefulness for pregnancy prevention in younger populations.

Despite many years of accrued safety and efficacy data, LARC initiation rates continue to be remarkably low in the relatively resource-rich setting as the US. Data published in 2010, and again in 2012 indicate that less than 1 in 10 women will have ever used a LARC method.

2,

10 Despite low overall uptake, LARC use is trending upward in all US women, increasing from 2.4% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009.

2 Older teens, aged 15 to 19, are less likely to use LARC (4.5%) than young adults, aged 20 to 24 (8.3%). Of LARC use in young women, IUDs predominate with the ENG implant comprising only 0.5% use in the adolescent age group.

11 Users of all ages report the confidence in efficacy and no interruption during the act of sex as important reasons for choosing LARCs, with high levels of user satisfaction reported across studies.

12

Issues Affecting Efficacy—Initiation

Despite proven safety, efficacy, ease of use, and improved adherence, low rates of initiation limit LARC usefulness in US AYA sexually active populations.

2,

9,

13 Young women are more likely to ever use LARC with the following associated characteristics:

Women less likely to use LARCs (and IUDs) include those with:

lower education;

external locus of control;

foreign language; and

sex outside of marriage (≥4 sexual partners, widowed, divorced, or separated).

Socioeconomic status as a predictive factor for LARC use varies across studies. A history of an adolescent pregnancy was associated with ever use of injected depot medroxyprogesterone (DMPA), but not IUD.

10As in cases of other health-related decisions, provider recommendation and confidence is among the reasons women select IUDs and ENG. Family planning experts have promoted LARCs as a first-line method of contraception for women of all ages for many years.

1 Despite excellent efficacy and safety profiles, many providers still do not recommend LARC use in AYAs. A 2012 study of pediatricians, nurse practitioners, social workers, and health educators in

New York City school-based health centers showed that only 55% of respondents were likely to recommend an IUD.

14 Only 77% believed that IUDs were safe for adolescents, with decreasing rates of provider confidence and recommendation associated with recent sexually transmitted infections (STIs), remote pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), nonmonogamous relationship, or nulliparity, all representing patient characteristics that are no longer contraindications to IUD insertion. In this study, over half of the professionals were also biased in believing that time required for counseling about LARC would be more excessive than for short-acting methods.

In addition to improving provider knowledge, confidence, and recommendations, another barrier to effective youth contraception is point of access at the facility level. Youth-oriented contraceptive programs may improve LARC uptake by offering improved inserter competence and accessibility, flexible hours, and open appointments, with additional social networking and education outreach in the community.

9 Youth-friendly programs have included facilities such as Planned Parenthood and Title X, and other specialty reproductive health-focused programs demonstrated increased rates of LARC use in younger women. Facility obstacles for LARC use in younger patients include device and insertion cost, inconvenience of clinic appointment and hours, provider misconceptions and lack of recommendation, and limited support and training for time of visit and in-clinic LARC insertion.

Both health systems and providers have ample room to improve access and offer evidence-based, patient-centered counseling, eliminating outdated and inaccurate information, in order to improve LARC initiation and continuation

(Table 44.1). Medical costs associated with LARC contraceptive use are far superior to other forms of shorter-acting hormonal contraception.

15Insert methods are safe, relatively painless, and simple procedures that are well tolerated in outpatient settings. Side effects are limited, with satisfaction levels consistently higher in LARC than short-acting method users. While LARCs clearly offer superior first-line contraception, providers must balance evidence and enthusiasm with patient autonomy and patient-centered care. Determining each young woman’s family planning needs and goals requires a contraceptive plan responsive to lifestyle, avoiding undesired side effects. To counsel adequately, providers must keep an open mind, as well as actively listen and engage adolescents to form and assume ownership of their own contraceptive planning and outcomes.

Initiation—Balancing Risk of Pregnancy with Quick Start

Initiation of LARC contraceptives need not be hindered or delayed depending on patient history and attitudes about pregnancy.

16,

17,

18 FDA Pharmaceutical Inspectorate indicates that LARC methods

should only be inserted within 5 days of last menstrual period (LMP), with a negative pregnancy test, and reasonable certainty that the patient is not pregnant. Family planning experts offer more flexible guidelines for starting LARCs as long as there is a reasonable certainty that the AYA is not pregnant. Determining potential for very early pregnancy that may not be detectable by urine human choriogonadotropic hormone testing includes inquiring about date or time of last unprotected sex (i.e., sex without birth control or a condom). If coitus occurred within 5 days, EC may be offered (see

Chapter 41). If unprotected sex occurred more than 14 days prior, and the pregnancy test is negative, providers may confidently insert both ENG and IUDs. Patients who are starting LARC after the 5-day window of the LMP should be strongly encouraged to use backup protection or abstain from intercourse for 7 days while the method takes effect.

If there is some possibility of fertilization and/or early implantation, some family planning experts have three options: