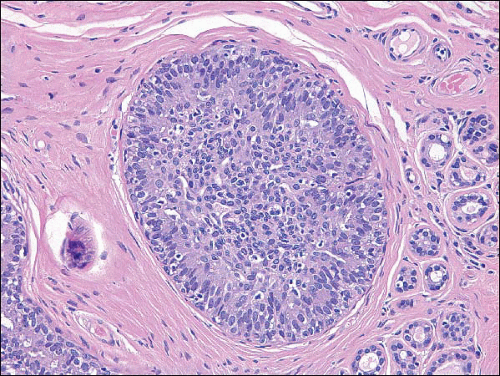

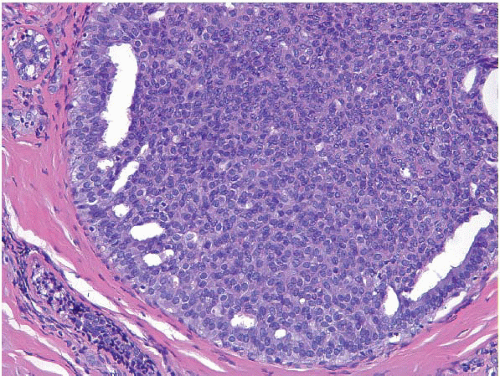

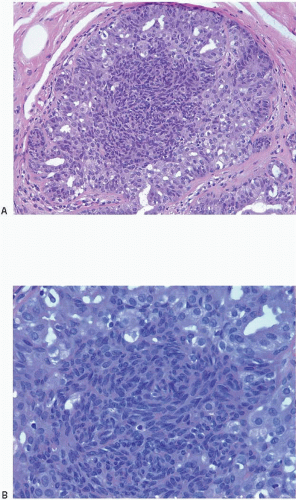

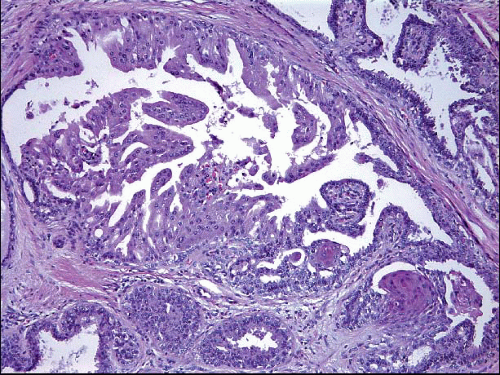

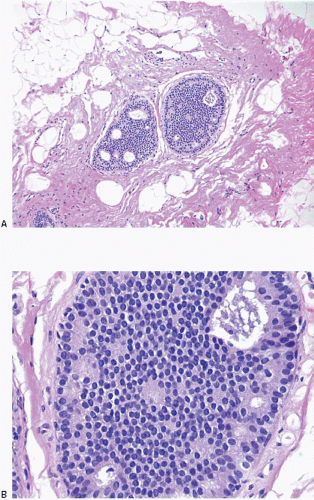

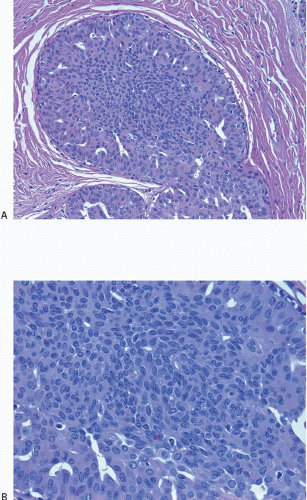

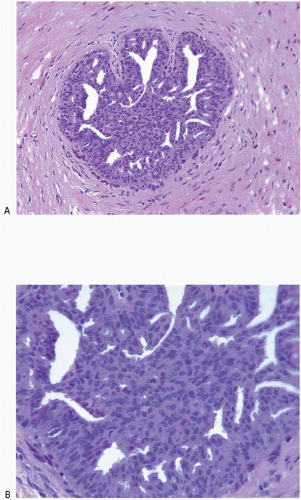

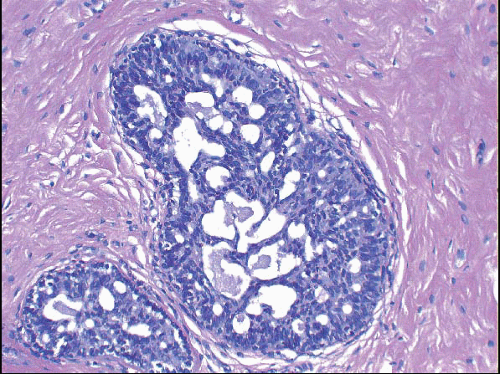

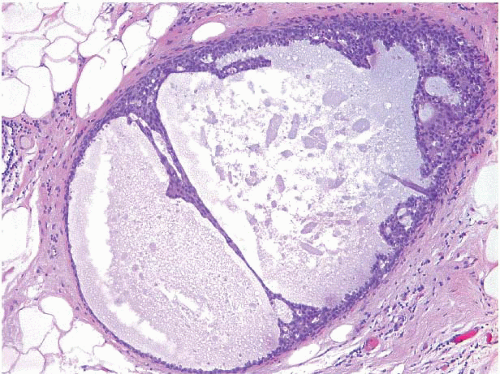

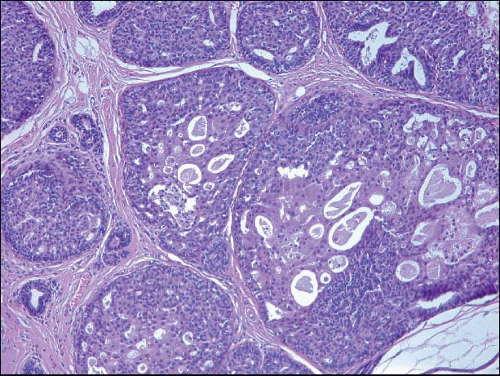

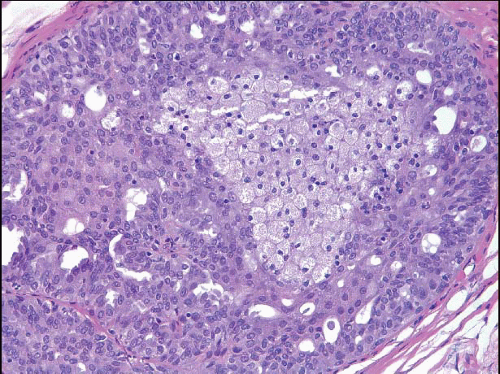

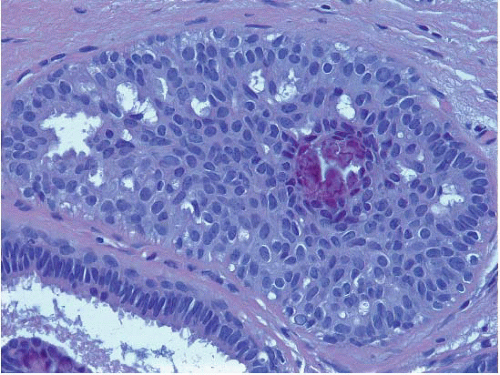

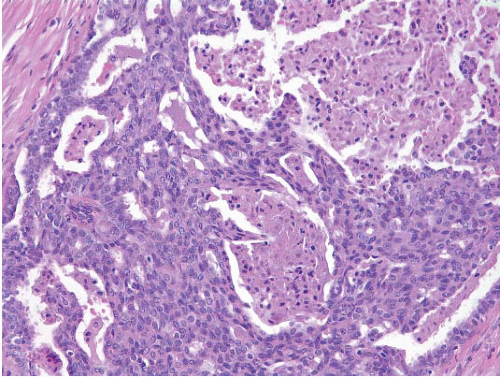

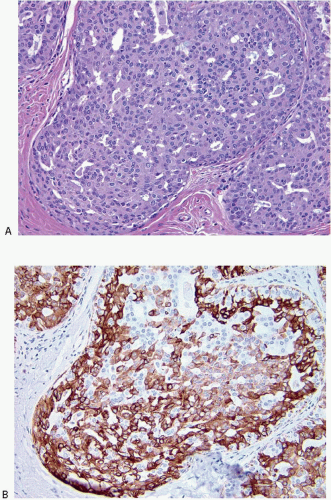

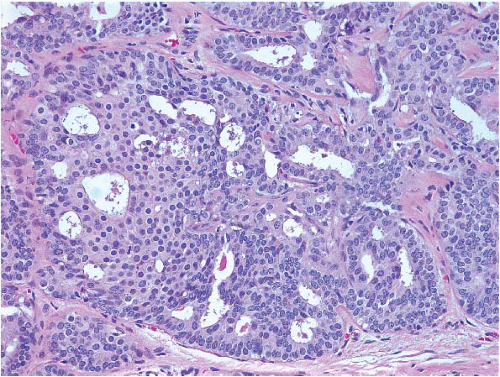

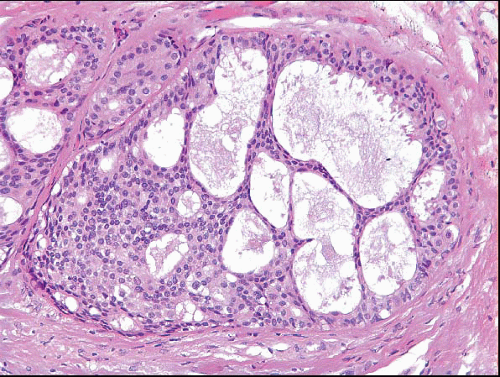

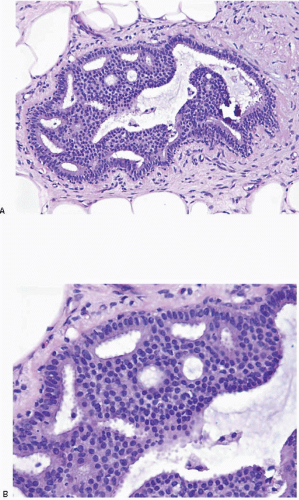

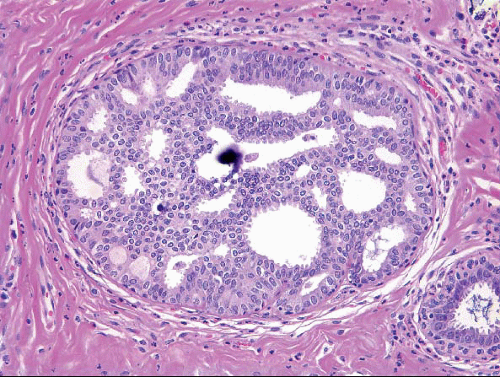

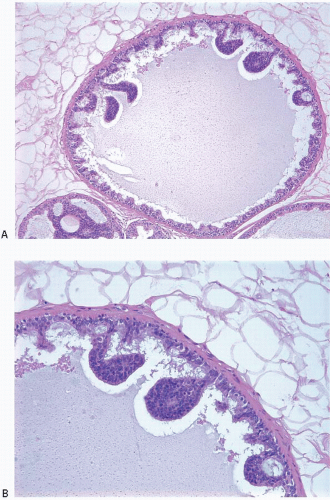

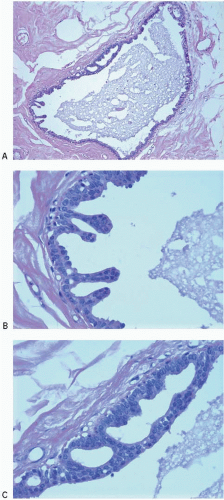

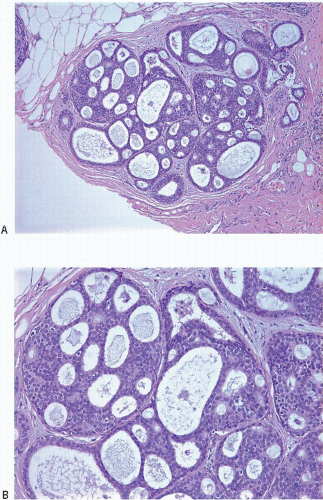

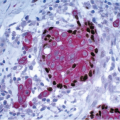

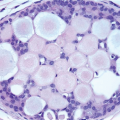

Also known as hyperplasia of the usual type, UDH is a benign epithelial proliferation characterized by a tendency for the proliferating epithelial cells to bridge across and often fill and distend the involved spaces. Mild forms show epithelial proliferation two to four cell layers thick, but these do not appear to be associated with the same increase in breast cancer risk seen with the more florid examples of UDH.

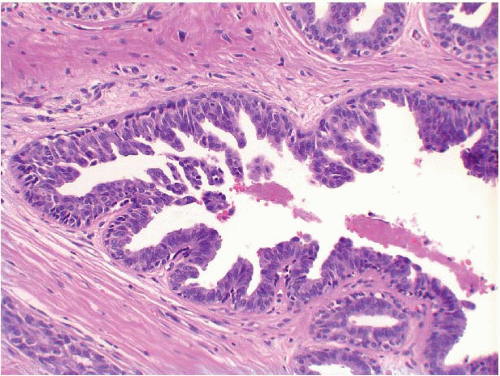

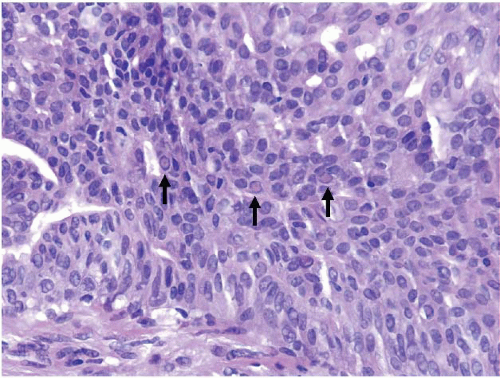

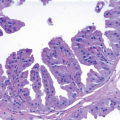

The proliferation in UDH may have a solid, fenestrated, or micropapillary architecture. If lumens are present within the proliferation, they are irregular and variable in size and shape, often slit-like, and frequently

arranged around the periphery. When epithelial bridges are present, they appear stretched or twisted and commonly show central attenuation. Micropapillary projections, if present, are typically tuft-like or elongated and tapering, resembling the pattern of hyperplasia seen in gynecomastia. The cells comprising UDH are cytologically benign; vary in size, shape, and orientation; are arranged in a haphazard pattern; and have poorly defined borders that may result in a syncytial appearance. The cells do not polarize around lumens within the proliferation. In some instances, there is prominent streaming or swirling of the cells. The nuclei vary in size, shape, and contour and may show overlapping. Nuclear grooves and intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions may be evident. These architectural and cytologic features of UDH are illustrated in

Figs. 3.1,

3.2,

3.3,

3.4,

3.5,

3.6,

3.7,

3.8 and

3.9 and

e-Figs. 3.1,

3.2,

3.3,

3.4,

3.5,

3.6,

3.7 and

3.8. Multiple cell types (including metaplastic cells with apocrine or, less often, squamous features) may be present (

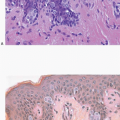

Figs. 3.10 and

3.11,

e-Figs. 3.9 and

3.10). Foamy histiocytes (

Fig. 3.12), as well as calcifications (

Fig. 3.13), may be seen in association with the proliferating epithelial cells. Rarely, foci of necrosis are present (

Fig. 3.14,

e-Fig. 3.11). Alterations in the surrounding stroma, such as fibroblastic proliferation, elastosis, and mononuclear cell infiltrates, are uncommon. The key features of UDH are summarized in

Table 3.1.

Immunophenotype and Genetics

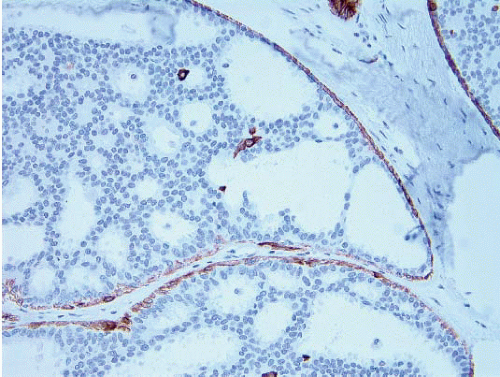

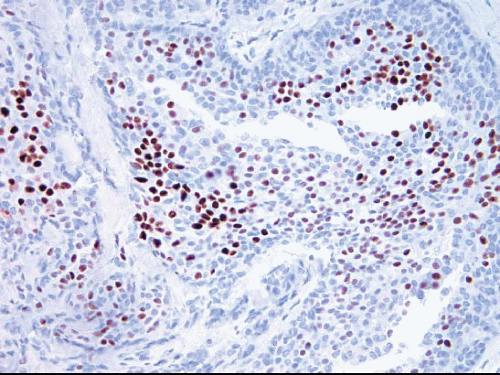

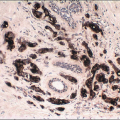

The cells comprising UDH show variable expression of estrogen receptor (ER) (

Fig. 3.15) as well as a low proliferation rate.

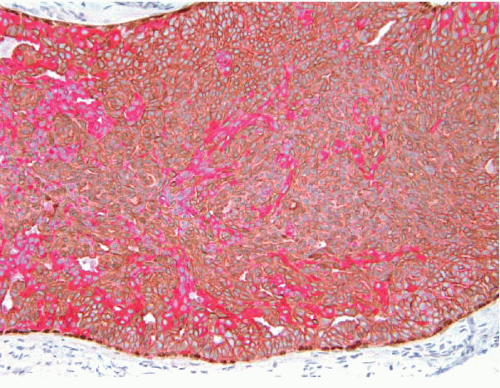

2 A mosaic pattern of expression of high-molecular-weight cytokeratins (CKs) as demonstrated with antibodies to CK5/6 is a characteristic feature (

Fig. 3.16,

e-Fig. 3.12).

3 The use of immunostain cocktails composed of antibodies to both low-molecular-weight (luminal) and high-molecular-weight (basal) CKs further highlights the heterogeneity of the cell population in UDH (

Fig. 3.17).

While a subset of UDH lesions show chromosomal losses and gains, most studies have found no consistent genetic alterations in these lesions. Moreover, UDH lesions share few genetic abnormalities with ADH, DCIS, or invasive breast cancer. This has led to the view that most UDH lesions do not represent direct cancer precursors, but rather are markers of a generalized increase in breast cancer risk.

4,

5

Clinical Course and Prognosis

UDH is associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in the risk of breast cancer, and the subsequent cancer may occur in either breast.

6,

7 This risk is slightly higher among women with UDH who have a positive family history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative.

8,

9 There are at present no prognostic factors or biomarkers that permit the identification of patients with UDH who are more likely to develop invasive breast cancer.