Upper GI bleeding

Peptic ulcer disease

Gastritis

Esophageal/gastric varices

Mallory-Weiss tear

Boerhaave’s syndrome

Malignancy

Lower GI bleeding

Diverticulosis

Angiodysplasia

Malignancy

Inflammatory bowel disease

Colitis (ischemic or infectious)

Hemorrhoids

Anal fissure

Solitary rectal ulcer

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Upper GI bleeding is characterized as bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz including the stomach, duodenum, and esophagus. Patients with upper GI bleeding may present with symptoms such as hematemesis (vomiting of fresh, bright red blood, coffee ground emesis) or melena (passage of black or tarry stools). It may also be occult and present with hemoccult positive stools or as a microcytic anemia. Symptoms of upper GI bleeding may include lightheadedness, orthostatic hypotension, and syncope related to blood loss and hypovolemia. Bleeding from the foregut is estimated to be five times more common that lower GI bleeding [11]. The mortality rate for hemorrhage from the upper GI tract has also been shown to increase with aging [6].

The most common sources of hemorrhage in the elderly are peptic ulcer disease and gastropathy which together account for between 55 and 80 % of patients presenting to the emergency department [12]. Esophagitis and esophageal/gastric varices account for the remaining sources of bleeding. Less common etiologies of hemorrhage include esophageal tears due to Boerhaave’s syndrome or Mallory-Weiss syndrome, duodenal diverticula, Dieulafoy’s lesion, angiodysplasia, hemobilia, aortoenteric fistulae, and neoplasms. History should focus on prior diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease, treatment for Helicobacter Pylori, smoking, alcohol use, previous abdominal surgeries, and steroid use. Liver disease is another key risk factor and may suggest variceal bleeding. Elderly critically ill patients are at increased risk for development of stress gastritis with mechanical ventilation, traumatic brain injury, major burn wound, or trauma injury all being known risk factors. Confounding factors include the use of anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, and recent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS).

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Intestinal bleeding from a source distal to the ligament of Treitz is considered to be a lower GI bleed. While lower GI bleeding is less common than upper GI bleeding in the general population, the incidence of lower GI hemorrhage is higher in the elderly. It is important to remember that one of the most common sources of blood per rectum is actually the upper GI tract, and therefore, upper GI bleeding should always be considered first and investigated as the source. Nearly 80 % of patients presenting with a lower GI hemorrhage will stop bleeding without intervention, however, the recurrence rate can be as high as 25 % [13].

The most common cause of lower GI bleeding is diverticulosis of the colon which is usually characterized by abrupt onset of painless hematochezia. Angiodysplasia is also a common cause of painless bleeding from the anus, especially in the elderly. It accounts for up to 30 % of lower GI bleeding in patients over the age of 65 years. A less common source is a colonic neoplasm where ulceration of the mucosal surface by the tumor results in bleeding. Bleeding from colonic neoplasms is often more subtle than diverticular bleeding and may lead to slow blood loss over a prolonged period of time. Less common etiologies include infectious colitis, mesenteric ischemia, and inflammatory bowel disease [14].

Obtaining a detailed history of the events related to the bleeding episode is crucial and should include the color and quantity of blood passed. Patients should be queried regarding any previous history of colon malignancy, diverticulosis, and personal or family history of inflammatory bowel disease. Anorectal bleeding should also be considered and may be characterized by bright red bleeding from hemorrhoids, a solitary rectal ulcer, or anal fissures.

Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Rarely, the source of hemorrhage is not identified by either colonoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and is then referred to as obscure GI bleeding. In these situations, the etiology of the bleeding may be from a small bowel source or may originate from a source in the upper GI tract or colon that was not visualized during prior diagnostic attempts. While obscure GI bleeding is less common than a defined upper or lower GI source, this cause of bleeding is often challenging to diagnose and treat and may lead to ongoing blood loss with prolonged hospital stays.

Diagnosis

Endoscopy

Endoscopy, including EGD and colonoscopy, is the diagnostic test of choice and may also allow for therapeutic intervention. EGD is safe and effective in the elderly population and has been reported to allow for a diagnosis in over 90 % of patients [7]. Colonoscopy and EGD generally require conscious sedation to ensure patient comfort and to allow for the technical completion of the study. Sedation is generally well tolerated in the elderly patient. A randomized controlled trial of geriatric patients comparing the use of midazolam versus saline for sedation during EGD found that treatment with midazolam increased the probability that patients would successfully tolerate the exam with no significant increase in the number of hypotensive episodes [15]. However, this study did find a significantly higher incidence of desaturation in geriatric patients sedated with midazolam, which is in agreement with previous studies [16]. Elderly patients may also be at increased risk of aspiration during upper endoscopy procedures and tolerate such events poorly due to underlying lack of physiologic reserve. Lastly, patients older than 80 years have been shown to have a greater risk of colon perforation during colonoscopy [17].

Angiography

Angiography is another useful modality in the diagnosis of GI bleeding. Angiography allows for localization of the bleeding source when the rate is as low as 0.5 ml/min. Diagnostic angiography is safe and well tolerated with risks including puncture site complications such as bleeding, hematoma, and pseudoaneurysm. There is also risk of acute kidney injury associated with the administration of iodinated intravenous contrast [18]. In addition to its diagnostic capabilities, angiography also possesses the added benefit of potential therapeutic intervention. Catheter-based interventions including vasopressin injection and angioembolization will be discussed later in this chapter.

Nuclear Medicine

Nuclear scintigraphy can be used to identify the source of intestinal bleeding and involves Tc-99m-labeled red blood cells or technetium-99m (Tc-99m) sulfur colloid. Radiolabeled red blood cells maintain their activity for longer periods of time compared to injection of Tc-99m sulfur colloid, allowing for serial imaging, and may give better results when used to diagnose lower GI bleeding. Nuclear scintigraphy is safe, noninvasive, and an accurate method of localizing the source of GI bleeding [19]. The benefits of this imaging technique for detecting GI bleeding include its sensitivity for very slow bleeding, with the ability to detect bleeding rates as low as 0.1 ml/min and its noninvasiveness [20].

Computed Tomographic Scanning

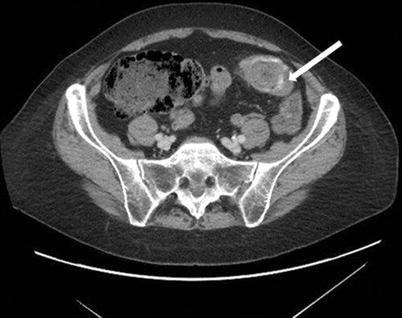

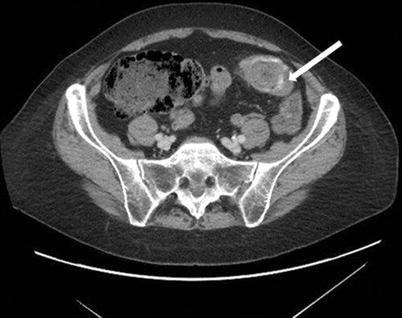

Contrast-enhanced multidetector-row helical computed tomography (MDCT) scanning is a newer technology which can be used to identify the area of intestinal blood loss. This technique of CT scan allows images to be obtained during the arterial phase of contrast administration which allows identification of contrast extravasation into the bowel lumen (Fig. 15.1). Areas concerning on the arterial phase can be further investigated using delayed images to assess for residual contrast, or pooling of contrast, which further supports the presence of active arterial bleeding. As with angiography, MDCT appears to be most effective in detecting active or symptomatic bleeding, however unlike angiography, MDCT has been reported to detect bleeding rates as low as 0.4 ml/min, similar to those for nuclear scintigraphy [6]. It also has the advantage of being noninvasive, widely available, avoids the risks associated with arterial puncture required for conventional angiography, and has the added benefit of identifying extraluminal pathology or causes of hemorrhage. However, MDCT is associated with complications related to the use of intravenous contrast administration and radiation exposure [19]. Using MDCT to diagnose the source of bleeding may be an efficient method to facilitate directed interventions via either endoscopy or angiography [21].

Fig. 15.1

Lower GI bleeding diagnosed by contrast-enhanced computed tomographic (CT) scan. The arrow indicates area of active arterial extravasation seen in the descending colon

CT Enterography

As the technology of CT scanning improves the sensitivity of imaging with the advent of multidetector imaging systems with 64 channels has improved image resolution and introduced more applications for the use of CT scans in the diagnosis of GI bleeding. CT enterography utilizes orally delivered, neutral contrast material which improves the visualization of pathology within the lumen of the intestine. The protocols require the oral administration of contrast in several doses at 20-min intervals in order to distend the lumen of the intestine. With the neutral background provided by the enterally delivered contrast material, active hemorrhage can be visualized and localized more easily than traditional CT scanning protocols. The large volume of oral contrast required to perform CT enterography does place elderly patients at risk of aspiration. CT enteroclysis is another option which delivers contrast enterally at a continuous rate via a nasojejunal tube which is placed under fluoroscopic guidance, potentially decreasing the risk of vomiting, reflux, and aspiration [22].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to diagnosis the cause of GI bleeding continues to evolve, however, it is currently considered to be experimental for localizing the source. However, its use in the evaluation of obscure GI bleeding has shown a diagnostic yield of only 40 % with improved localization of pathology in the distal small bowel compared to the proximal small bowel [23]. MRI enterography has a low-diagnostic yield for identifying intraluminal small bowel bleeding sources causing occult GI bleed, however, this imaging has been shown to identify extraintestinal pathology which may aid in the diagnosis of the cause of hemorrhage [24]. Further studies are needed to define the role of MRI in the diagnosis of occult GI bleeding; however, it may be an adjunctive diagnostic test to consider in patients with bleeding sources not localized by other, more traditional imaging techniques.

Capsule Endoscopy

Improvements in technology have allowed for the more widespread use of capsule endoscopy to aid in the diagnosis of obscure GI bleeding. The capsule, which is the size of a large pill, is swallowed and advances the length of the GI tract through peristalsis. Capsule endoscopy is especially useful in identifying the etiology of small bowel blood loss with imaging completed to the cecum in nearly 75 % of cases [25]. This technology is purely diagnostic with a yield near 50 % but unfortunately does not allow for intervention [26–28]. Clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of capsule endoscopy for obscure GI bleeding have shown a diagnostic yield between 30 and 68 % with angiodysplasia the most common diagnosis [29–31]. The test is well tolerated and safe, with retained capsule representing the most significant risk associated with this procedure [32, 33].

Management

Initial Evaluation

As with any acute illness associated with blood loss, the initial assessment of GI bleeding should include evaluation of the airway, breathing, and circulation. The patient should be evaluated in the appropriate level of care with frequent monitoring of vital signs. With significant hemorrhage, patients should have two large bore IV’s placed for transfusion of blood or IV fluids as needed. The primary treatment goals in patients presenting with a major intestinal bleed include adequate resuscitation, localization and/or diagnosis of the cause of hemorrhage, and control of the bleeding source with endoscopy, angiography, or surgery. A nasogastric tube may be placed and saline lavage performed to give some insight as to whether the bleeding is originating from an upper GI source. A Foley catheter should be placed to monitor urine output and assess the response to fluid resuscitation. If the index of suspicion is high for an upper GI source of bleeding, high dose proton pump inhibitor infusion therapy should be initiated.

Aspiration Risk in Elderly

Elderly patients who are hospitalized with GI bleeding have been shown to experience complications early in their hospital course, frequently within 96 h of admission [34]. Among the most frequent complications are pneumonia and aspiration [12]. Therefore, airway protection and pulmonary toilet are of significant importance during the resuscitation and hospitalization of patients presenting with GI bleeding.

All patients should be administered supplemental oxygen and the head of bed should remain elevated at all times. Supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula is an important adjunct at the time of endoscopy as it has been shown to prevent hypoxemia, oxygen desaturation, and cardiac arrhythmias [35]. Consideration should be given to early, prophylactic intubation in order to secure the airway and limit the risk of aspiration. This is especially true in patients undergoing endoscopy who will be receiving conscious sedation. Elderly patients generally require lower doses of sedative medications during endoscopic procedures compared to their younger counterparts [36]. However, older patients may experience an unexpected respiratory arrest that may necessitate emergent endotracheal intubation further increasing the risk of aspiration. Paradoxic reactions to conscious sedation which may result in altered mental status are also more frequent in the elderly making endoscopic interventions difficult [6]. Current guidelines from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommend heightened attention to the dose and effects of standard sedatives used during endoscopic procedures on the elderly and emphasize the importance of lower initial doses of sedatives with more gradual titration [37].

Fluid Resuscitation

Normal saline and lactated ringers are the most common resuscitation fluids used in the treatment of hypovolemic shock. Studies comparing the use of normal saline and lactated ringers in patients with acute hemorrhage show equivalent outcomes [17, 38]. There is a theoretical risk of hyperkalemia with the use of lactated ringers which may be exacerbated in patients with acute kidney injury or chronic renal insufficiency seen in many elderly patients. Resuscitation with colloids has theoretical benefits over crystalloid resuscitation due to its ability to restore intravascular volume more efficiently due to the higher oncotic pressure resulting in decreased losses into the extravascular space. This may be beneficial in elderly patients as colloid resuscitation may allow for lower total infusion volume required to restore intravascular volume. Unfortunately, several studies have compared crystalloid versus colloid resuscitation showing no statistical benefit with colloid resuscitation [39, 40]. A large randomized controlled trial compared 3,497 patients who received 4 % albumin to 3,500 patients receiving normal saline [15]. This study found no significant difference in mortality, need for renal replacement therapy, or hospital length of stay suggesting no benefit in the use of colloid resuscitation compared to crystalloid resuscitation.

Recent research from the trauma population suggests that early transfusion of blood products may be beneficial in patients with acute hemorrhage. Not only does early transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) appear to be superior to crystalloid resuscitation in patients with hemorrhage, but the transfusion of other blood components may be beneficial as well. Studies suggest that transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelets in addition to PRBCs may decrease mortality [13]. The optimal transfusion strategy appears to be a 1:1 ratio of FFP to PRBCs [19]. Studies also suggest that increasing the ratio of platelets to PRBCs may be beneficial as well [41].

Medications

Elderly patients who are diagnosed with GI bleeding should be queried regarding their current medication regimen with particular focus on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Laboratory studies including complete blood count, PT/INR, and PTT should be measured to diagnose any derangements in the clotting cascade. Classical measures of coagulopathy may not address all coagulation abnormalities and thus may fail to correctly diagnose coagulopathy. The classical measures fail to measure platelet dysfunction due to medications or fibrinolysis. Limitations of these traditional laboratory measures of coagulopathy have led to increased interest in the use of alternative measures of coagulation, clot strength, and fibrinolysis. Thromboelastography (TEG) and thromboelastometry (TEM) are an established method for measuring the viscoelastic properties of blood for hemostasis testing [3, 14, 23]. TEG and TEM have the benefit of providing detailed information on clot formation and clot strength and provide results more rapidly than conventional measures of coagulation.

Treatment with fresh frozen plasma is a common method used to reverse anticoagulation in patients taking Coumadin. FFP is effective; however, it takes time to transfuse and may require the infusion of large volumes of fluid in order to correct the INR. In elderly patients who are actively bleeding, strategies need to be considered that more rapidly correct the coagulopathy and prevent large volume infusions that may be problematic in patients with comorbid disease such as congestive heart failure. Pharmacologic agents such as factor VIIa and prothrombin complex should be considered as they result in rapid correction of the clotting abnormality and require minimal volume infusion.

Recombinant factor VIIa has traditionally been used as a treatment for uncontrolled bleeding in patients with hemophilia. It has been used to treat GI bleeding in patients with liver disease and in the treatment of trauma-induced coagulopathy [22, 24]. Randomized controlled trials have failed to show improvements in mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute upper intestinal hemorrhage compared with placebo [42, 43]. There are case reports which suggest that recombinant factor VIIa may be a useful strategy in elderly patients with GI hemorrhage who are poor candidates for aggressive intervention, however, further randomized controlled trials will be need to define its role in treating acute bleeding from the GI tract the elderly [44]. There are concerns regarding increased thromboembolic complications, particularly those affecting the arterial circulation, associated with the use of Factor VIIa. Therefore, while the use of Factor VIIa may be a useful strategy to quickly reverse coagulopathy in patients, its risks and benefits must be weighed carefully.

Several studies have compared the use of prothrombin complex to FFP and vitamin K for reversal of coagulopathy following injury or in anticipation of an invasive procedure. These studies have concluded that prothrombin complex corrected the INR more quickly and effectively than the combination of FFP and vitamin K. Coagulation was normalized 30 min after administration of prothrombin complex. Treatment with prothrombin complex is generally safe; however, the reversal of coagulopathy is not as durable as that achieved with vitamin K. Further studies are needed to better define the role of prothrombin complex in the treatment of elderly patients with GI bleeding, but it should be part of the armamentarium in the treatment of the exsanguinating patient.

Patients on antiplatelet medications such as clopidogrel (Plavix), and to a lesser degree aspirin, experience alterations in the platelet function that may cause coagulopathy which contributes to ongoing bleeding. Point of care testing is available to determine the degree of platelet inhibition caused by clopidogrel, which can vary significantly among patients [34]. Treatment with platelet transfusion can be considered in bleeding patients with pharmacologically induced platelet inhibition despite normal platelet counts.

While Coumadin therapy prolongs the INR, which allows for a quantification of the clotting abnormality, newer antithrombotic medications may not cause any changes in basic laboratory measures even when therapeutically anticoagulated. Medications such as dabigatran (Pradaxa) and other new direct thrombin inhibitors have effects that cannot be measured by conventional clinical laboratory assays, and TEG and TEM are required to detect their effects. Currently, the therapeutic effect of these agents cannot be reversed with conventional interventions such as FFP, platelet infusion, or recombinant factor VIIa making management of patients difficult. Dabigatran can only be removed by hemodialysis which is difficult to perform in patients with ongoing hemorrhage [35].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree