A 21-year-old male student, HB, was referred to the Diabetic Clinic of his local hospital. He had been feeling unwell for about 4 weeks, noticing a marked increase in thirst, passage of large volumes of urine both during the day and at night. He felt generally tired and unwell and had lost about 6 kg in weight over the preceding month. Physical examination was normal. A diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes was made on the basis of a random blood glucose of 25 mmol/L and the presence of glucose and ketones in the urine. HB was started on insulin therapy and subsequently managed with a ‘basal-bolus’ regimen, taking an injection of short-acting insulin 30 minutes before meals and intermediate-acting insulin at bedtime. His symptoms improved over the next few weeks and he attended the clinic for dietary advice and education about testing his own blood glucose, managing hypoglycaemic attacks and monitoring for complications.

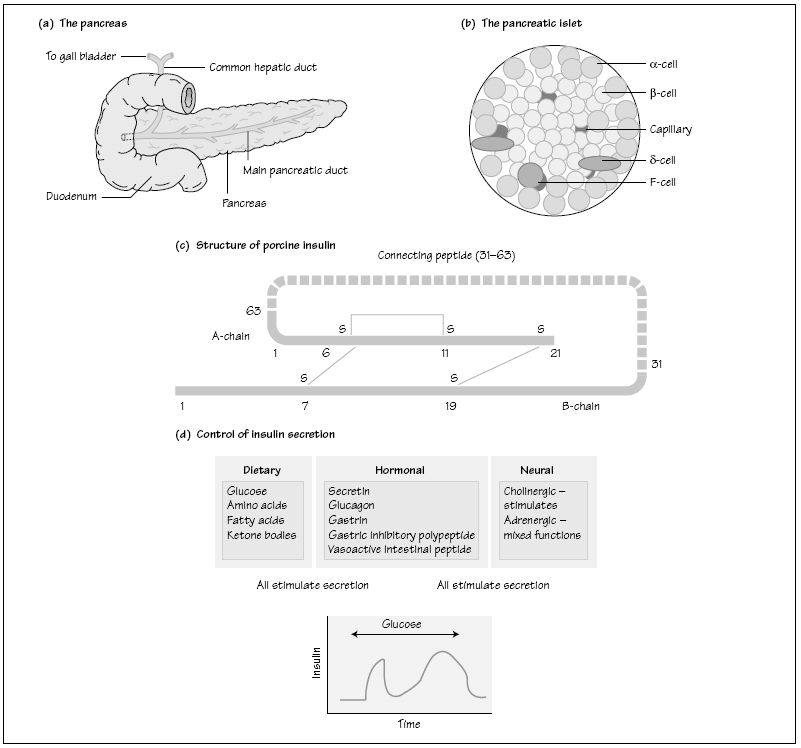

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition causing destruction of the pancreatic β cells (see below). Treatment of Type 1 DM is with insulin, administered as subcutaneous injections by the patient. Therapy is tailored to the individual patient and is commonly given as biphasic insulin containing short and intermediate acting insulins and administered twice daily or as a ‘basal-bolus’ regimen with intermediate insulin given at bedtime supplemented by short-acting insulin before meals. Patients monitor their blood glucose concentrations using capillary blood glucose testing strips and a portable glucometer.

Glycated haemoglobin reflects diabetic control over a period of weeks to months, reflecting erythrocyte lifespan (120 days) and is used to assess glycaemic control in patients with diabetes. The most commonly reported fraction is haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which is increased in diabetes by covalent bonding of glucose. The rate of formation of HbA1c is directly proportional to blood glucose concentrations.

The pancreas lies closely adjacent to the duodenum (Fig. 38a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree