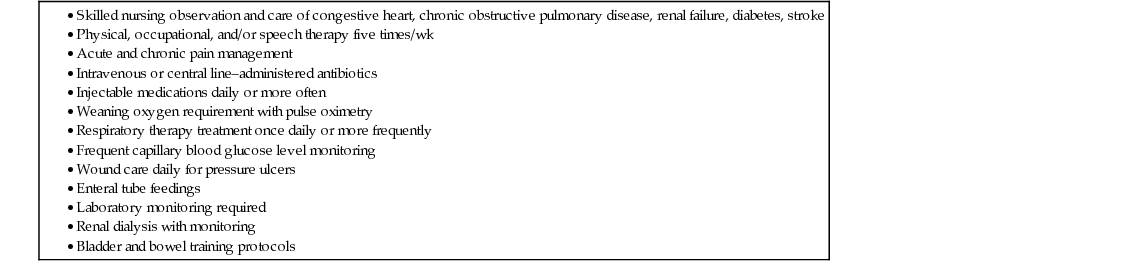

Joseph G. Ouslander The purpose of this chapter is to give readers a brief perspective on institutional long-term care (LTC) in the United States. The focus will be on assisted living facilities (ALFs) and nursing homes (NHs). In the United States, NHs are also commonly referred to as nursing facilities and skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). For ALFs, most states use the term assisted living, but some use residential care or other similar terminology. Other types of LTC facilities exist, and some care for younger patients but, given the focus of this text, the care of the geriatric population in ALFs and NHs will be highlighted. ALFs and NHs provide health, social, and recreational services to chronically ill people who, for medical, functional, psychological, and/or social reasons, choose not to live in their own homes. Most ALFs and NHs are for-profit businesses and operate independently of each other. However, in many areas of the United States, there are campuses with independent living units, an ALF, and a NH in close proximity, and home care services are also commonly available. In these continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs), individuals pay an up-front entry fee (or purchase a unit) and live the rest of their lives on the campus, guaranteed a higher level of care when they need it. Because of the community nature and resulting high quality of care common in CCRCs, this is becoming an increasingly popular choice for older adults who can afford it. There are several fundamental differences between U.S. ALFs and NHs (Table 125-1). First, ALFs are generally more like senior housing based on a social model, as opposed to the predominant health care focus of NHs. Although ALFs care for relatively well and functionally impaired older adults, and many have dementia units, the level of functional disability in NHs is generally higher, and medical acuity is higher in NHs that have a high volume of patients admitted immediately after an inpatient hospital stay (referred to subsequently as postacute care). NHs also care for medically complex and disabled younger people, a population that comprises 10% to 15% of the NH population. Thus, the availability of licensed nurses is highly variable in ALFs, whereas a minimum number are required in NHs. Similarly, physicians are not required or frequently present in ALFs, but NHs are required to have a medical director, and those admitted to NHs are required to be certified for this level of care and have a primary care physician of record. Residents of ALFs generally go to a physician’s offices for their primary care, although some ALFs have established clinics, and physicians and other health care professionals can provide services on site. ALFs generally have limited access to on-site pharmacy services and diagnostic testing, whereas NHs are required to have pharmacy consultants, generally have ready access to medications through an on-site or contracted pharmacy, and have ready availability of a variety of diagnostic tests (e.g., blood work, electrocardiography, x-rays and, in some cases, other imaging procedures). ALFs are generally smaller and vary in size more than NHs; the average bed capacity of a NH is close to 100 beds, and some are much larger. State and federal regulations that oversee care in ALFs are generally less stringent than those in NHs. NHs are subject to an extensive code of federal regulations related to safety and clinical care. Finally, care is paid for very differently in the ALF versus the NH setting, as will be discussed. TABLE 125-1 Characteristics of Assisted Living Facilities (ALFs) and Nursing Homes (NHs) Close to 95% > 65 yr, most with impairments in instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs) and some with impairment of basic ADLs Many ALFs have dementia units 85% to 90% > 65 yr, almost all with impairments in basic ADLs Population is heterogeneous depending on characteristics and goals of care (short vs. long stayers; see Figure 125-1) Almost all private pay In some states, Medicaid will support ALF care for the poor. Medicare will pay for home care for a temporary period of time after an acute illness. Medicare will pay for up to 100 days of skilled care after acute illness for patients who meet specific criteria. Medicaid pays for close to two thirds of care in U.S. NHs. The remainder is private pay. Key staff are residential care coordinators and aides. Availability of licensed nurses variable Other clinical staff usually not on site Availability of registered nurses and licensed practical nurses mandated at specific levels Most hands-on care provided by certified nursing assistants Other interdisciplinary team members usually on site (e.g., social worker, rehabilitation therapists, etc.) Physicians usually not present on site No requirement for medical director Physicians and physician extenders (NPs, PAs) usually present > once/wk Medical director required Despite the growth of community-based, long-term care programs that strive to maintain older adults in their own homes, the need for institutional LTC continues to grow in the United States. This is in large part because of the increasing longevity and corresponding functional disability among those who live to extreme old age, decreasing number and geographic proximity of children (especially daughters, who provide the most support to functionally impaired older Americans and who are increasingly joining the work force, thus limiting their caregiving abilities), and economic factors. Although the number of NHs has stayed the same or decreased slightly over the last decade, the number of ALFs has grown substantially, and care for many functionally impaired older adults who would have previously been admitted to NHs. Economic factors are also critical in determining the need for institutional LTC, and are very different in countries with a national health program combined with more ready availability of in-home social support. Thus, to understand the role of institutional LTC in the U.S, one must understand how LTC is financed. Health care for older Americans is funded in one of four basic ways: (1) private health insurance; (2) Medicare; (3) Medicaid; and (4) out-of-pocket expenditures. Although many insurance companies sell long-term care policies, private insurance still plays a relatively small role in paying for LTC at the present time. Medicare is a federally administered health insurance program for those aged 65 years or older and for a smaller number of younger people who are severely medically disabled and/or who have end-stage renal disease requiring renal replacement therapy. The vast majority of older Americans qualify for basic Medicare coverage by contributions that they or a spouse have made during their working years. Most older Americans still incorrectly believe that Medicare will pay for LTC. It is not until they or a relative needs LTC services that reality sets in. Less than 10% of overall Medicare expenditures go to LTC. Medicare does not pay for in-home support for assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) on an ongoing basis and does not pay for care in an ALF. Medicare will pay for time-limited skilled services (nursing, rehabilitation therapy) at home or in an ALF after a hospitalization for people who are home-bound. Medicare will also pay for up to 100 days of care in a NH after an acute illness (20 days are fully covered, and thereafter there is a substantial co-payment), but only in certain situations. To qualify for Medicare reimbursement, admission to the NH must follow a 3-day stay in an acute-care hospital, and the patient must require continuous skilled nursing care and/or active rehabilitation with carefully documented potential and progress to achieve a lower level of care. This so-called 3-day rule is highly controversial and incentivizes hospitalizing older people so that they can receive the Medicare benefit for postacute care. This rule is waived for some types of managed care programs (see later). Patients recovering from surgery, hip fracture, or stroke with good rehabilitation potential, patients with unstable medical conditions (e.g., those requiring intravenous medications), and patients with multiple chronic illnesses who have become deconditioned in the hospital resulting in new functional disability are examples of patients who will qualify for Medicare coverage for postacute care in an NH (Table 125-2). However, the average coverage period is approximately 25 days because patients have reached their maximum medical and rehabilitative benefits, and Medicare will no longer pay for their care. Patients with dementia and other chronic functional disabilities, on the other hand, are viewed as requiring custodial institutional LTC and do not qualify for Medicare coverage. TABLE 125-2 Characteristics of Short-Stay Postacute Patients in Nursing Homes Thus, the vast majority (>60%) of funding for institutional LTC comes from out-of-pocket expenditures or Medicaid. Medicaid is a state-administered medical welfare program for the poor; one has to have very limited income and assets to qualify, and benefits vary among the 50 states. This has created a phenomenon termed spend down—older Americans must spend down their assets to pay for institutional and noninstitutional LTC until they become poor enough to qualify for Medicaid, which will then cover LTC costs. Because private pay rates for most LTC facilities are in the range of $4,000 to $10,000/month (and in some cases higher), spend down occurs relatively quickly for most older Americans who enter an institutional LTC setting. In many areas of the United States, the growth of managed capitated systems of care is also substantially affecting LTC. Nationally, approximately one third of older Americans have opted into a Medicare Advantage plan, which is a managed capitated program administered by an insurance company. In these managed capitated systems of care (previously known as a health maintenance organization [HMO]), the insurance company receives a fixed rate for a Medicare beneficiary each month. One of the main ways of saving money in this system is to reduce the number of acute hospitals days. As a result, patients in these health plans are being discharged rapidly from acute hospitals into NHs while still subacutely ill. In addition, because in most capitated systems there is no 3-day acute hospital requirement for Medicare reimbursement of postacute care in a NH, some acutely ill patients may completely bypass the acute hospital. For example, patients in a Medicare Advantage program with deep vein thrombosis or mild pneumonia or cellulitis requiring intravenous antibiotics may be directly admitted to a NH, without an acute hospital stay. These economic incentives are driving the growth of a higher level of skilled care in NHs and are resulting in an unmet need for more highly trained nurses and physicians in this setting. ALFs are a growing entity in the continuum of LTC in the United States. In 2011 to 2012, there were over 700,000 residents of over 22,000 ALFs and similar residential facilities. Almost 80% of ALFs are owned and operated by a for-profit business. Most ALFs have a 25-bed capacity or less, about one third have 26 to 100 beds, and about 5% have more than 100 beds. ALFs are residential units that can provide additional services to residents, including meal preparation, laundry, housekeeping, incontinence care, and medication management. The vast majority of ALF residents need assistance with several instrumental ADLS and with at least one basic ADL. In general, the more assistance a resident needs, the higher the monthly payment. Older adults needing skilled nursing care, intensive rehabilitation, and/or who have complex multimorbidity and functional impairments generally require placement in a NH. Many ALFs have, however, adopted an aging in place philosophy, which has led to many very impaired individuals continuing to live in an ALF. Many also have locked dementia units. This has in turn created concerns over safety issues and quality of care. Preventable and treatable conditions may not be optimally identified, evaluated, and managed in the ALF setting.1–3 Most ALFs are managed by a full-time care coordinator and a number of nursing assistants. ALFs may have one or more licensed nurses present during daytime hours or who are available on-call for emergencies. Because ALFs do not receive Medicare funding, they are outside the purview and regulation of federal laws and are regulated in varying degrees on a state-by-state basis. The vast majority of ALFs do not have on-site medical oversight by a physician or a so-called physician extender (e.g., nurse practitioner [NP], physician’s assistant [PA]). Medical care is provided by a resident’s primary care physician and, usually, transportation to and from the physician’s office must be arranged. Although ALF costs are on average substantially less than NH care, this cost remains unaffordable to many low- and moderate-income older adults. Medicare does not pay for care in an ALF unless the resident qualifies for an episode of skilled care after an acute illness. In this situation, a home health agency can come into the ALF and provide nursing and rehabilitation therapy on a temporary basis. Medicaid only pays for ALF care on a limited basis and only in some states. Thus, ALF care is an out-of-pocket personal expense for older adults choosing to live in this setting.

Institutional Long-Term Care in the United States

Overview

Characteristics

Assisted Living Facilities

Nursing Homes

Model of care

Residential with supportive services

Nursing, rehabilitative, and medical care

Residents

Payment for care

Size

Most <25 beds, about one third have 26-100 beds, only 5% have >100 beds

Average size is 100 beds; one third larger than 100 beds

Ownership

About 80% are for profit.

About two-thirds for profit

Staff

Availability of clinical services

On-site diagnostic testing and pharmacy services uncommon

Most, especially in urban areas have on-site availability of diagnostic testing and pharmacy services.

Medical care

Regulations

Federal regulations not as stringent as for nursing homes; state regulations vary considerably

Subject to extensive code of federal regulations focused on safety, environment, and clinical care

Financing of Long-Term Care

Assisted Living Facilities

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Institutional Long-Term Care in the United States

125