Abstract

Owing to improved treatment and survival of persons with brain and spinal cord tumors, the rehabilitation community has demonstrated an increasing interest in inpatient rehabilitation outcomes in this population. The studies available show that patients with brain and spinal cord tumors make functional gains in inpatient rehabilitation with high rates of discharge to the community. When compared with their noncancer counterparts with similar impairments, persons with brain and spinal cord tumors tend to have shorter lengths of stay and higher rates of acute transfers. Furthermore, although more studies are needed, current research indicates that inpatient rehabilitation is correlated with improved quality of life and survival. This chapter reviews the current literature on this topic.

Keywords

Acute transfer, Brain tumor, Discharge to community, Functional independence measure (FIM), Inpatient rehabilitation, Karnofsky performance status (KPS), Length of stay, Quality of life, Spinal cord tumor, Survival

Introduction

Inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with brain and spinal cord tumors plays a distinctive role in their cancer care continuums. This chapter focuses on inpatient rehabilitation outcomes in such patients with respect to function, length of stay (LOS), discharge to community, acute transfers, quality of life (QoL), and survivorship. The management and treatment of brain and spinal cord tumors as well as impairments and complications commonly affecting these patients are covered elsewhere in this book.

Rehabilitation of patients with brain and spinal cord tumors undoubtedly presents a unique challenge, as a result of the medical and therapeutic complexities associated with these cancer diagnoses. There are a broad range of associated impairments which include but are not limited to cognitive and/or communication deficits, dysphagia, aphasia, hemiplegia, paraplegia, tetraplegia, spasticity, contractures, pressure ulcers, and neurogenic bowel and bladder.

Inpatient rehabilitation of noncancer patients with stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), or spinal cord injury (SCI), who may present with some of the abovementioned impairments, has been well established. Intuitively, the same rehabilitation principles should be applied to patients with brain and spinal cord tumors. However, the key differences between patients with brain and spinal cord tumors and their noncancer counterparts are the uncertainties associated with cancer, which include prognosis, progressive functional decline, medical complexity, and concomitant chemotherapy or radiation, to name a few. These, in addition to financial considerations, likely explain why such cancer patients may be less likely to be admitted to acute inpatient rehabilitation.

In order to assess the value of inpatient rehabilitation for patients with brain and spinal cord tumors, as well as their candidacy for it, it is pivotal to evaluate the functional improvements made in inpatient rehabilitation as well as other outcomes such as LOS, discharge to community, acute transfer rate, QoL, and survivorship. It has been suggested that selection of patients for inpatient rehabilitation is often based on prognosis for survival and anticipated functional outcome on discharge.

Evidently, patients with brain and spinal cord tumors do benefit from inpatient rehabilitation. Patients with brain tumors show improved functional scores that are maintained after discharge. These improvements are achieved regardless of tumor type, lesion, and presence of metastasis. Additionally, patients with brain tumors make similar functional gains to stroke and TBI patients, despite shorter LOSs. Similarly, patients with spinal cord tumors have been found to have improved Functional Independence Measure ( FIM) scores, as well as improved mood, QoL, and survival after inpatient rehabilitation. Such promising results warrant the attention of providers to admitting and selecting brain and spinal cord cancer patients to acute inpatient rehabilitation when appropriate.

Description of Outcome Measures

Functional Independence Measure (FIM): The FIM is an 18-item, clinician-reported scale that assesses function in six areas including self-care, continence, mobility, transfers, communication, and cognition. Each of the 18 items is graded on a scale of 1–7 based on level of independence in that item (1 = total assistance required, 7 = complete independence). FIM scores can be measured at admission to and discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. The difference between the admission and discharge scores constitutes the FIM change or FIM gain. FIM efficiency refers to the rate of FIM change with time.

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS): A clinician-reported scale that rates patients’ global performance status on a scale of 0–100, scored in intervals of 10. A score of 0 signifies death, while a score of 100 indicates normal function with no evidence of disease.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status: A clinician-reported scale comparable to the KPS, scored from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating “Fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction,” and 5 indicating death.

Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM): A validated and sensitive tool used to detect functional improvements in traumatic and nontraumatic SCI. It has been suggested as a more optimal tool to assess functional outcomes in patients with spinal cord tumors as opposed to the FIM.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain (FACT: BR): A 54-item scale used to assess QoL in patient with brain tumor using Likert scales. The tool assesses QoL components, including physical, social, emotional, and functional well being, in addition to other considerations.

Outcomes: Brain Tumor

Functional Outcomes

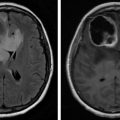

Several studies have shown improvement in functional status in patients with brain tumors who undergo inpatient rehabilitation. Marciniak et al. showed that patients with both primary and metastatic tumor types improved functionally after inpatient rehabilitation, with comparable total FIM change (motor and cognitive) and equivalent FIM efficiencies across all tumor groups. Similarly, Tang et al. showed that patients with brain metastasis, glioblastoma multiforme, and other brain tumors made functional gains from inpatient rehabilitation admission to discharge.

In a study that prospectively evaluated 10 patients with brain tumors, Huang et al. showed significant functional gains as measured by the FIM, the disability rating scale (DRS), and the KPS score. FIM and DRS scores improved from admission to discharge to 3-month follow-up, whereas KPS scores only showed significant improvement from admission to 3-month follow-up. Their study shows that functional gains are sustained at 3 months and suggests that the KPS may not be useful in detecting more subtle changes.

A more recent, larger study examined the effect of inpatient rehabilitation on functional outcomes in 100 patients who underwent surgical resection after newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. The study showed that 93.7% of patients had improvement in functional status from admission to discharge, with the largest gains in mobility, self-care, communication/social cognition, and sphincter control. Additionally, 22% of the patients were deemed to be “high responders” who improved a minimum of two levels of independence based on FIM scores from admission to discharge.

Comparing Functional Outcomes in Relationship to Other Factors

Several studies have attempted to further characterize the functional gains made by patients with brain tumors in inpatient rehabilitation with regard to tumor type, tumor recurrence, and concomitant therapy.

Marciniak et al. did note a difference in motor FIM gains across tumor types (lowest gains in meningioma and astrocytoma compared with metastasis and “other”); however, such differences were deemed secondary to differing LOSs. Similarly, a retrospective review of charts comparing 21 patients with low-grade astrocytoma with 21 patients with high-grade astrocytoma by Fu et al. showed that while both groups made functional gains, the patients with high-grade astrocytoma had higher total FIM gains (21.7 vs. 13), but again likely secondary to longer LOS (13 vs. 9 days). FIM efficiencies were comparable in the two groups. Thus it appears that patients with more advanced tumors such as metastatic tumors and high-grade astrocytomas had higher FIM gains, but likely due to longer LOS.

With regard to tumor recurrence, Marciniak et al. showed that patients with recurrence had lower FIM motor gains and FIM efficiencies compared with those patients undergoing rehabilitation after initial tumor diagnosis.

With respect to concomitant treatment, Marciniak et al. also found that patients receiving concomitant radiotherapy had greater motor FIM efficiency scores, thought likely due to tumor shrinkage. However, the authors also note that patients who received radiotherapy tended to not have tumor recurrence. In contrast, Tang et al. showed that concomitant treatment with chemotherapy or radiation was not a predictor of FIM gain.

Length of Stay

Several studies between 1998 and 2006 show that brain tumor patients undergoing inpatient rehabilitation have LOSs between 18 and 25 days. A later study by Fu et al. showed even shorter LOS in high- and low-grade astrocytoma patients (13 days vs. 9 days, respectively).

Discharge Home

Patients with brain tumors show relatively high rates of discharge home after inpatient rehabilitation, with most studies reporting rates between 80% and 92%. Tang et al. showed slightly lower rates of 76%, 72%, and 70% in glioblastoma, metastatic tumors, and other tumors, respectively.

Acute Transfer

While most studies have not measured the rate of acute transfers as a primary outcome, several have reported it. Marciniak et al. showed an acute transfer rate of 25%. Several have compared such rates with that of the rate of acute transfer in TBI and stroke patients as in the following sections.

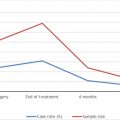

Quality of Life

Poor functional status has been linked to poor QoL in cancer survivors, including patients with brain tumors. To date, few studies have specifically examined the correlation between inpatient rehabilitation functional and QoL outcomes in patients with brain tumors. In one study, Huang et al. used the FACT-BR measure to assess QoL in a prospective study of 10 patients with brain tumors. They found insignificant improvement in scores from admission to discharge, with significant improvement between admission and 1-month follow-up and admission and 3-month follow-up. This was deemed likely to the fact that patients only perceived improvement in QoL when they were able to reintegrate back into their home and community environments. Of note, functional levels on the three scales measured (FIM, DRS, KPS) did not correlate with FACT-BR scores, which the authors note is similar to the results in three prior studies. Similarly, Kim et al. found insignificant improvements in QoL (using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30) in 25 brain tumor patients undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. As in Huang’s study, the authors felt that longer follow-up was necessary to evaluate the effect of inpatient rehabilitation on QoL.

Survival

Inherent to cancer rehabilitation as a whole is the question of survival and prognosis as it pertains to function. The study by Tang et al. showed that positive prognosis was associated with high FIM gain, low dexamethasone dose, and lack of organ metastasis in patients with brain metastasis. In patients with glioblastoma, low admission dexamethasone dose and high FIM gain indicated better survival prognosis.

Roberts et al. also examined survival time in their study of patients with glioblastoma multiforme who underwent inpatient rehabilitation. They reported a median survival time of 14.3 months in patients who underwent inpatient rehabilitation versus 17.9 months in patients who did not undergo inpatient rehabilitation; however, this was not statistically significant after adjustment for confounders (age, extent of resection, and KPS score). They concluded that the lack of survival difference in the two groups may be clinically relevant in the sense that the patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation had lower KPS scores than those who did not require inpatient rehabilitation, presumably due to worse overall clinical condition and potentially worse prognosis. They thus argue that inpatient rehabilitation may have “level[ed] the survival prognosis” for these patients with initial lower function. Namely, inpatient rehabilitation provided a survival benefit to these patients. Additionally, this study noted that “mobility responders” or patients with FIM mobility gains trended toward longer survival.

Comparison to TBI and Stroke

As the neurologic impairments in patients with brain tumors are similar to those in stroke and TBI, several studies have compared outcomes in patients with brain tumors to those in patients with TBI and stroke, as inpatient rehabilitation in these groups is well established.

O’Dell et al. retrospectively compared outcomes after inpatient rehabilitation in patients with brain tumors with those in a group of case-matched patients with TBI. They found that although the absolute FIM gains were higher in the TBI group, FIM efficiencies were comparable, likely due to the shorter LOS in the brain tumor group (18 days vs. 22 days). Also, there was a trend toward higher gains in patients with diagnosis of meningioma, lesions in the left hemisphere (thought due to generally poorer outcomes in right-sided lesions, due to neglect), and those not receiving concomitant radiotherapy. Discharge home rates were comparable in the two groups (82.5% in the brain tumor group vs. 92.5% in the TBI group). The rate of acute transfer in the brain tumor group was 7.5% versus 0% in the TBI group.

Huang et al. also compared patients with brain tumor to those with TBI and found no significant difference with regard to total admission and discharge FIMs or FIM efficiencies. Admission cognitive FIM was lower in the TBI group. As in O’Dell’s study, FIM change was higher in the TBI group. The tumor group had lower LOSs and greater discharge to the community—TBI patients were more likely to be discharged to institutionalized settings (26% vs. 13.4%). It is thought that patients with brain tumors may have better family support hence increased rates of discharge home. In contrast to O’Dell’s study, side of lesion did not result in differences in the rehabilitation LOS. Bilgin et al. more recently performed a similar study comparing patients with TBI and brain tumor, using lesion side and gender as matching criteria. They found that patients with TBI had initial lower functional status but displayed better functional recovery than patients with brain tumor. As in Huang’s study, lesion side had no effect on functional outcome in either group.

Similarly Huang et al. retrospectively compared outcomes in patients with brain tumors to those in stroke patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation. They reported no significant difference between the two groups with regard to total admission FIM, total discharge FIM, total FIM change, or FIM efficiency. However, stroke patients did experience greater change in ADL-FIM scores from admission to discharge as compared with their counterparts with brain tumors. On the other hand, patients with brain tumors had higher motor FIM scores. There were no significant differences in cognitive FIM between the two groups. With regard to LOS, the brain tumor group had significantly shorter LOS than the stroke group (25 days vs. 34 days). Discharge to the community was greater than 85% in both groups. Additionally, LOS for patients with right-sided stroke was an average of 10 days longer than in patients with right-sided tumor. Also, the right-sided stroke group experienced higher rates of ADL-FIM change than their right-sided tumor counterparts.

In another study, Greenberg et al. compared rehabilitation outcomes in patients with brain tumors (meningiomas and gliomas) who survived craniotomy to those with stroke. They found similar functional outcomes in all groups tested, with shorter LOS in patients with brain tumor (24 days for the meningioma group, 23 days for the glioma group, 75.4 days for the stroke group). FIM efficiency was found to be lower (although not statistically significant) in the stroke group likely secondary to increased LOS.

Finally, Bartolo et al. compared 75 patients with brain tumor (meningioma and glioblastoma) status post neurosurgery (rehabilitation started within 2 weeks of surgery) with a control group of 75 matched stroke patients. They found improvement in function across both groups. Subgroup analysis showed that patients with meningioma had significantly higher FIM motor and ADL gains as compared with patients with glioblastoma or stroke. These differences were thought to be secondary to the benign nature of meningiomas as compared with glioblastomas. With regard to the stroke group, the differences were thought to be due to the ischemic or hemorrhagic nature of brain damage as opposed to the “space-occupying” nature of meningiomas. Overall they show that early rehabilitation after surgery is key.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree