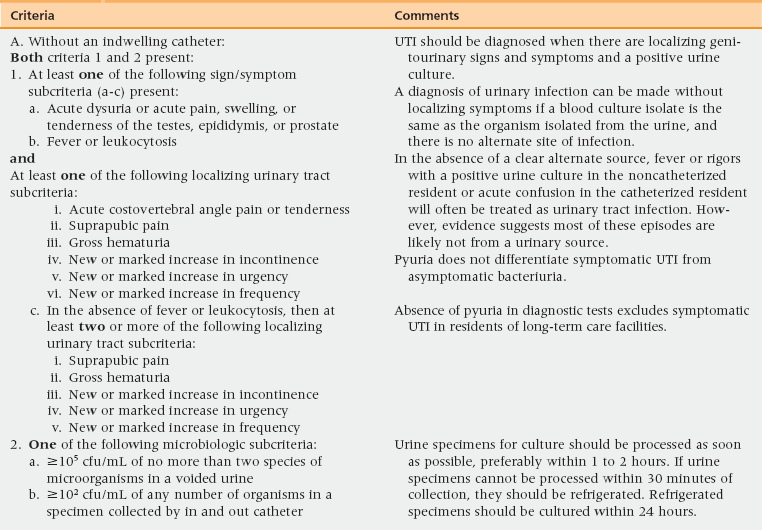

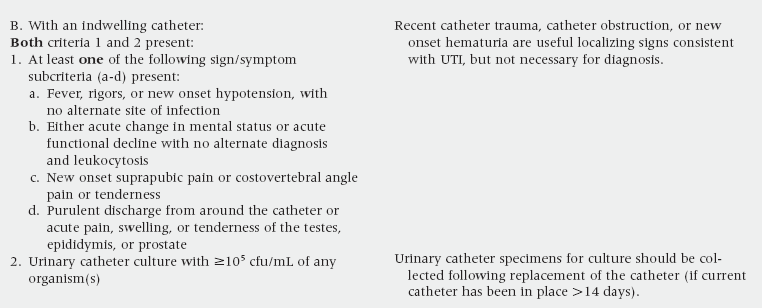

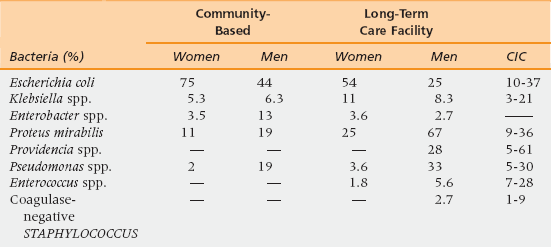

49 General Pathophysiology and Risk Factors General Principles of Diagnosis, Assessment, and Management Lower Respiratory Tract Infection (LRTI) Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI) Gastrointestinal (GI) Infection Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Recognize the most common causes of infection in older adults. • Understand how the causes of infections in older adults vary with the place of acquisition. • Understand how the clinical presentation of infection differs with increasing age. • Understand how to manage, treat, and prevent the most common infectious syndromes found in the older adult. Despite medical advances, infection remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the aged. When considering causes of infection in older adults, it is important to know where the infection was acquired, what infections are most common in those settings, and what microorganisms cause those infections. Urinary tract infection (UTI), lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), and skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) are the most common infectious syndromes seen among older adults regardless of whether the infection was acquired in the community, in a nursing home, or in a hospital. Bloodstream infections (BSI) are reported more frequently among older adults who are in hospital, whereas a wider variety of gastrointestinal (GI) infections are found among community-dwelling elderly and nursing home residents. Overall rates of infection in nursing homes and hospitals are similar, but those in chronic care settings are generally thought to be less severe.1–5 Delayed recognition that an older patient is infected can result in delayed treatment. As a consequence, the elderly are more likely to die from their infections; their mortality is twofold to twentyfold higher than in young adults.6–9 Why the elderly are at increased risk of infection with poor outcome is a complex question. Predisposing risk factors for infection include immunosenescence, frailty with impaired functional status, increased prevalence of predisposing comorbid illnesses, exposure to pathogens within institutional settings, and complications of medical treatment.10 Changes in the immune system are found with normal aging. However, all aspects of the immune system of the older adult are not necessarily affected or depressed to the same degree. The most prominent impact of age is seen on the acquired or adaptive immune system. The adaptive immune system recognizes new infections through generation of specific T-lymphocytes and antibody-producing B-lymphocytes. Age-related defects have been described predominantly in T-cells. Other acquired conditions in the elderly, such as malnutrition, can contribute to further decline in T-cell function. T-cells are important for host defenses against pathogens that can reside within cells. Antibody production is essential to facilitate uptake and killing of encapsulated bacteria by phagocytic cells (Box 49-1). Neoplasms seen with increasing frequency in older adults can contribute to depressed antibody production and function. Defects in antibody response may explain why some responses to vaccinations and outcomes from infections are often poor in the aged.11 Recognition that the older patient has an infection may be delayed in part because his or her symptoms and signs of infection are atypical. Clinicians may also ascribe complaints or abnormal physical findings or complaints to preexisting illnesses and not consider infection as the cause. In addition, cognitively impaired older adults may not be able to perceive symptoms of infection or communicate them to their healthcare provider.12,13 The febrile response may be blunted or the onset delayed. Furthermore, appropriate increases in body temperature of 2° F or 1° C diagnostic of fever may not be recognized because the normal temperatures of older adults are lower at baseline. In addition, other markers of inflammation such as leukocytosis may be lacking. In one study, 48% of infected older adults were afebrile and 58% did not demonstrate significant leukocytosis. Because of a lack of an inflammatory response, more than half of older adults may not have localizing symptoms of infection, and focal findings for infection may be minimal or absent on physical examination.13–24 Many older adults take medications with antiinflammatory effects, such as aspirin, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, corticosteroids, cytokine inhibitors, and antineoplastic agents that may further cloud the interpretation of the patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory findings. Therefore, it is not surprising that the diagnosis of infection is often missed or delayed in the elderly. Therefore, it is essential to consider infection in the older patient even if typical signs and symptoms are absent.12–24 Diagnosis of infection in older adults is further compromised by limited access to laboratory and diagnostic procedures in some settings. There is also a lack of diagnostic algorithms that have been specifically validated for use in the elderly. Recently, the McGeer Criteria were updated following a rigorous systematic review of the scientific literature related to the diagnosis of infectious syndromes in older adults.25 Although these criteria are intended for the retrospective detection of infections acquired in nursing-home residents, they may provide a useful evidence-based conceptual framework for the clinician who is trying to diagnose infections in the elderly (Tables 49-1 to 49-4). TABLE 49-1 Criteria For Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) cfu/mL, colony forming units per microliter. Adapted from Stone ND, Ashraf MS, Calder J, et al. and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology Long-Term Care Special Interest Group. Definitions of infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities: Revisiting the McGeer criteria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:965-77. The following sections discuss a few aspects of the general diagnostic approach that have been shown to be of potential use in the assessment for infection in older adults.13–29 An acute change in the ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADLs) has been shown to be predictive of infection 77% of the time in nursing home residents. Acute change in functional status is a simple and potentially important clue that infection might be present.12,13 A temperature of 101° F or higher is a highly specific indication of infection, but many older adults will not achieve this definition for fever. Alternative definitions for fever have been recommended as more sensitive means to detect infection in older adults. It has been shown that a fever threshold of 100° F or higher detects 70% of infections in nursing home residents with a specificity of 90%. Other definitions of fever in the elderly include a 2.4° F increase over baseline temperature or higher than 99° F orally or 99.5° F rectally.13,25 Dehydration may accompany fever and suggest possible infection in this population. Nonspecific findings of decreased oral intake, dry mucous membranes, or furrowed tongue could be important clues that fever and infection are present.13,27–29 The Confusion Assessment Method can be performed rapidly to differentiate delirium from other chronic psychiatric conditions with high interobserver reliability, high sensitivity (>94%), and high specificity (90%-100%) (see Chapter 16).13,25,26 A complete blood count is one laboratory test that has been shown to be highly predictive of infection in older adults. Presence of leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and left shift may be useful if present when evaluating the elderly patient with suspected infection (neutrophilia is present with >14,000 leukocytes/mm3; left shift is present with >6% bands or ≥1500 bands/mm3).13,24,25 The decision to start antibiotic therapy should be based on the patient’s clinical condition. All patients with possible infection do not require urgent treatment. If urgent treatment is needed, then the choice of antibiotic should be based on the most likely clinical syndrome, the common organisms causing that condition, and knowledge of local antibiotic resistance patterns. Decision algorithms for when to begin treatment have been developed for nursing home residents (Table 49-5).30–32 TABLE 49-5 Minimum Criteria for the Initiation of Antibiotics in Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities Adapted from Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term-care facilities: Results of a consensus conference. Infection Control Hosp Epidemiology 2001;22:120-4. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, costovertebral angle. *Fever is defined as a single temperature of >100° F (>37.9° C) or >2.4° F (>1.5° C) unless otherwise stated. **Delirium is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. ***Does not include nonbacterial infections (herpes), deep tissue, or bone infection; noninfectious causes such as burns, thromboembolic disease, and gout can be mistaken for skin/soft tissue infection. The optimum route of antibiotic administration may be influenced by the severity of the patient’s clinical condition and access to health care resources. Intravenous or intramuscular therapy may be preferred in the patient with an ileus in whom absorption of an oral antibiotic is not guaranteed. If intravenous therapy is preferred, broad-spectrum penicillins plus a beta-lactase inhibitor, second generation cephalosporins, and carbapenems generally treat a variety of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative bacilli including methicillin-susceptible staphylococci (MSSA) and penicillin-susceptible enterococci. Penicillins cannot be given intramuscularly and many of the beta-lactam antibiotics are limited by their frequent dosing intervals. If the patient is penicillin-allergic or if antibiotic resistance is a concern, combination therapy with several antibiotics may be necessary. In the past, we could assume that antimicrobial-resistant bacteria were found primarily in health care settings where antibiotic use is most intense. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (DRSP), and multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli are still found primarily in hospitals, nursing homes, and in patients recently discharged from those facilities. However, emergence of community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) and multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections in healthy older people has become an increasing problem. Some strains of gram-negative bacilli, particularly Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, have become increasingly resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics because of the production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases. These strains are typically resistant to all third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins (ceftazidime and cefepime), extended-spectrum penicillins (piperacillin), monobactams (aztreonam), and many other antibiotic classes (quinolones, sulfonamides). Dependence on the carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem) as the last resort to treat severe gram-negative infections is greatly threatened by the emergence of carbapenemase-producing strains.33–37 Because of increasing antibiotic-resistant strains in hospitals, nursing homes, and in the community, it is imperative that providers ask themselves if patients with positive cultures, particularly for MRSA, VRE, or ESBL-positive bacteria have significant symptoms and signs of infection that warrant antimicrobial therapy rather than observation. In general, treatment of asymptomatic colonization with these bacteria will not permanently eradicate the organism, prevent infections, or improve patient outcomes. UTI is the most common infection seen in older adults in the community, nursing home, or hospital. Overdiagnosis is common. Many clinicians erroneously assume that only a positive urinalysis and culture are required for diagnosis. It is well established that significant but asymptomatic bacteriuria (≥105 colony-forming units [cfu] per mL) increases with age and debility.25,38–43 Urinary obstruction and stasis can also occur as a consequence of normal aging and local or systemic comorbid disease. In males, prostatic hypertrophy that occurs with normal aging can lead to obstruction, urinary stasis, and increased frequency of UTI. Neoplasms and stones that occur with increasing age may lead to obstruction and infection throughout the urinary tract. Cystocele, cerebrovascular accident, and diabetic neuropathy may impair bladder emptying and encourage the development of urinary stasis and bacteriuria.44,45 A major dilemma for clinicians is differentiating UTI from asymptomatic bacteriuria. Presence of significant pyuria (≥10 white blood cells per low-power field) in older adults is not a useful indicator of urinary tract infection. A significant proportion of asymptomatic older adults (30%) will have significant and persistent pyuria. Pyuria can be found in conditions such as nephrolithiasis and primary diseases of bowel found adjacent to the urinary tract such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and intraabdominal abscess. Absence of pyuria is useful, however. A negative urinalysis for pyuria is 99% predictive that bacteriuria, and hence UTI, is not present. Alternate diagnoses should be pursued.43–45 The diagnosis of UTI rests principally on patient history of symptoms and physical signs referable to the urinary tract (see Table 49-1).25 The symptoms and signs must be new or worsening of chronic symptoms. Symptoms of lower UTI or cystitis include suprapubic pain, dysuria, frequency, and urgency. Flank pain and fever are more typical of upper tract infection or pyelonephritis. Odiferous or cloudy urine indicate the presence of metabolites, urine concentration, crystals, and sediment and are not useful indicators for the presence of a UTI.44,45 Even in the cognitively impaired nursing home resident, physical signs referable to the urinary tract can be helpful especially if they resolve with treatment. Reproducible pain over the external genitalia (in a male), bladder, or flanks in the presence of significant bacteriuria and pyuria provides presumptive evidence that a UTI is present. In nursing homes, only 10% of fevers are caused by a urinary source. As a result, fever associated with change in mental status is rarely the result of a UTI and another cause should be sought. Special consideration might be given to patients with urinary catheters; 50% who have fever will have secondary bacteremia with the same organism present in urine.25,44–49 If an older adult has significant bacteriuria, pyuria, and symptoms, then treatment for UTI is appropriate. However, treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria does not permanently eradicate the organism and, with rare exception, no benefit of treatment for the older adult has been demonstrated in terms of improved well-being, relief of chronic symptoms, or survival. Change to One exception is the treatment of patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria who undergo a prostatic resection; postoperative bacteremia is substantially reduced in that population. Otherwise, treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is a major cause of inappropriate antibiotic use and emergence of antibiotic resistance. Education of clinicians regarding the importance of this problem poses a major challenge for antimicrobial stewardship programs.25,43 Predictability of the infecting organism and its response to treatment relates in part to gender, general health, and anatomy of the genitourinary tract. Many postmenopausal women have had a history of UTI throughout their lives that responds predictably to empiric treatment directed against Escherichia coli (uncomplicated UTI) (Table 49-6). Uncomplicated UTI requires that the woman be healthy without diabetes and immunosuppression. In addition, there are not functional or anatomic abnormalities of the urinary tract or the need for catheter use. An uncomplicated UTI cannot be nosocomially acquired.44,45,50 TABLE 49-6 Bacterial Etiologies Vary with Residence among Older Adults with Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) CIC, Chronic indwelling catheter. Adapted from Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection. In: Yoshikawa TT, Rajagopalan S, editors. Antibiotic therapy for geriatric patients. New York: Taylor & Francis Group; 2006, p. 487-501; and Nicolle LE. In: Yoshikawa TT, Norman DC, editors. Infectious diseases in the aging: A clinical handbook. 2nd ed. New York: Humana Press; 2009, p. 165-180. Women with an uncomplicated cystitis do not necessarily require culture prior to initiation of treatment unless they have symptoms of pyelonephritis, they have recurrence of symptoms, or if local antibiotic resistance is a concern (Table 49-7). Otherwise, the optimum antibiotic treatment of urinary symptoms in older adults should be based on culture results and antimicrobial susceptibilities. In the event that symptoms are severe with impending sepsis, then empiric antibiotic choices can be initiated based on local epidemiology data and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Use of nitrofurantoin may be limited in older adults because of contraindications in patients with renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <40 cc/min). Fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin are not indicated for pyelonephritis. The duration of treatment for cystitis and pyelonephritis is dependent on the antibiotic chosen (see Table 49-7).50 TABLE 49-7 Treatment of Woman with Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) IV, Intravenous; TMP/SMZ DS, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double-strength. *Avoid if early pyelonephritis suspected. Adapted from Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:e103-20. Topical estrogen use may reduce recurrent episodes of UTI in healthy older women by normalizing vaginal pH and restoring normal flora. Cranberry juice may reduce significant bacteriuria in older women by inhibiting binding of gram-negative bacilli to uroepithelial cells. Prophylaxis with postcoital or once-daily low doses of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, quinolones, or nitrofurantoin may be considered on older women as well as younger women with uncomplicated and recurrent UTI.44,45 For the remainder of the elderly with UTI symptoms who have abnormal urinary tract anatomy, require a urinary device, or are exposed to antibiotic-resistant pathogens in hospitals and nursing homes (complicated UTI), appropriate management requires obtaining a urine sample for culture and antimicrobial susceptibilities because their infecting organisms and treatment responses are not predictable (see Table 49-6). Most of these patients have reinfection with a new organism rather than relapse with the same organism.44–46 By definition, when UTIs in men occur, they have a complicated UTI because urinary tract abnormalities or catheter use is invariably present. In contrast with uncomplicated UTI in healthy older women, bacteriuria in healthy men is most commonly the result of not only E. coli, but also of Proteus mirabilis and enterococci. In hospitalized elderly patients with complicated UTI, E. coli is still the predominant pathogen, but Pseudomonas aeruginosa occurs with increasing frequency, followed by Candida albicans and other antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Chronic catheter-use has been associated with infections resulting from Providencia stuartii and coagulase-negative staphylococci. True polymicrobial infection can occur in elderly institutionalized patients even in the absence of an indwelling catheter.44–46 In the clinically stable patient, therapy can be withheld until culture results are known. When the diagnosis of UTI is uncertain, empiric antibiotic use may obscure the true diagnosis. Empiric treatment of complicated UTI should be based on the place of acquisition and primarily directed against gram-negative bacilli. For patients with complicated UTI, therapy must be reevaluated once culture and antimicrobial susceptibilities are available given the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance within and outside health care settings.44,45 Duration is based on response to symptoms and predisposing factors. For patients with short-term catheters in whom the catheter is removed and there are no upper tract symptoms, 3 days of antibiotic treatment may be sufficient. Some recommend 5 to 7 days if the patient is not severely ill and the clinical response is prompt. Longer therapy of 10 to 14 days is recommended for a delayed response (Box 49-2). If there is a relapse of symptomatic bacteriuria, a longer course of antibiotics may be needed to eradicate a chronic bacterial prostatic focus. Use of antimicrobial agents that penetrate prostatic tissue (quinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin) is required for 6 to 12 weeks.44–46 Management of patients who do not have symptoms localized to the urinary tract or cannot report them present a particular problem, particularly in nursing homes. Febrile nursing home residents that meet criteria for fever and delirium could receive empiric therapy with close reevaluation. For a patient with frequent and transient episodes of mental status that do not meet criteria for delirium, a trial of intravenous fluids to treat dehydration and promote urinary tract flushing could be considered. Alternatively, a trial of empiric antibiotics could be started, but stopped at 72 hours if the evaluation is negative for urinary abnormalities, the patient does not improve on empiric therapy, or another diagnosis becomes evident. UTI can be excluded if improvement is seen but the bacterial isolates found are not susceptible to empiric antibiotic choices. Treatment of bacteriuria related to chronic indwelling urinary devices should be considered only when typical symptoms are present or fever is present without another focus evident. A randomized trial found that nursing homes that used this algorithm had similar outcomes and reduced antibiotic use compared with nursing homes that were randomized to usual care.30,31,46 Follow-up samples of urine for culture should be obtained only if symptoms of infection persist or recur to verify if a secondary infection with a new organism resistant to therapy has emerged during treatment. In addition, ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) should be considered if fever or bacteriuria fails to improve on appropriate therapy or if the patient has recurrent UTI to rule out the presence of obstruction or abscess. Surgical or pharmacologic relief of obstruction or stasis may be effective, particularly if the patient has relapsing episodes of UTI with the same organism.44,45 Indications for urinary catheter use and alternative means of toileting should be reviewed, especially if incontinence and convenience are the only indications. Intermittent urethral catheterization may be associated with fewer infections. Routine catheter changes or irrigation with antimicrobial agents is not effective in preventing infection. Suppressive antibiotics can reduce the frequency of recurrent UTIs in spinal cord patients with chronic catheters, but resistance rapidly emerges.46 Pneumonia and bronchitis are common causes of hospitalization among older adults. They comprise the second most common cause of infection in nursing homes; rates of pneumonia range from 33 to 114 cases per 1000 residents per year or 0.3 to 2.5 episodes per 1000 days of resident care.51–54 Despite advances in antibiotics, vaccines, and other treatments, LRTI remains one of the top ten causes of death in older adults.51–54 Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a problem in the United States; approximately 15,000 cases of illness are diagnosed each year and a disproportionate number of infections are found among the elderly. Most cases of TB disease occur in community-dwelling elderly persons, but nursing home residents are at greatest risk for poor outcomes.55,56 Risk factors for LRTIs are particularly common in older adults either because of the consequences of aging, acquired conditions, or treatment of those illnesses. Microaspiration and inhalation of potential oral flora pathogens is an everyday occurrence. Multiple host defenses reduce the likelihood that pneumonia will develop in the normal host. Pathogens are contained by respiratory tract mucus, local inflammatory responses, and secretory antibodies. Pathogens are removed by expectoration of sputum through the actions of ciliated respiratory epithelium and cough reflexes. Swallowed pathogens are killed by gastric acid.51–54,57 Handling respiratory secretions appropriately is a major barrier to the development of pneumonia. Common neurologic and psychiatric conditions or sedating medications can impair recognition that aspiration is occurring or result in a swallowing disorder.51–54 Achlorhydria may result as a consequence of aging itself or from the use of medications that neutralize or block the production of stomach acid. Age-related declines in lung elasticity, respiratory musculature, and kyphosis contribute to diminished cough reflexes. Common conditions such as obstructive airways disease, emphysema, bronchiectasis, and presence of neoplasms can also reduce mucociliary clearance.51–54 Normal aging, age-associated conditions, and their treatments also result in changes in oropharyngeal flora. Alterations in oropharyngeal environment allow the flora to change from predominantly gram-positive cocci to carriage with gram-negative bacilli.51–54,58 Older adults also have more exposure to pathogens that cause respiratory disease through more frequent interactions with health care settings.58 Acquisition of respiratory pathogens via inhalation of droplets (influenza) or airborne pathogens (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) is less common. Older adults generally acquired asymptomatic latent TB infection (LTBI) when they were young and the infection was prevalent. Aging and conditions that lead to waning cell-mediated immunity increase the likelihood that reactivation of symptomatic TB disease will occur.55,56

Infectious diseases

General prevalence and impact

General pathophysiology and risk factors

General principles of diagnosis, assessment, and management

General symptoms

Changes in functional status

General signs and laboratory findings

Fever

Dehydration

Delirium

Complete blood count

Management

Empiric therapy versus culture-based treatment

Urinary Tract Infection

Categories

Minimum Criteria

Fever*

No catheter

One or more of the following: new or worsening urgency, frequency, suprapubic pain, gross hematuria, CVA tenderness, urinary incontinence

Fever

Chronic indwelling catheter

New CVA tenderness and rigors without cause or new onset delirium**

Respiratory Tract Infection

Categories

Minimum Criteria

High fever

>102° F (>38.9° C)

Respiratory rate >25 breaths/minute or productive cough

Fever

≤102° F (≤38.9° C)

Cough plus one of the following: tachycardia >100 beats/minute, delirium, rigors, respiratory rate >25 breaths/minute

Afebrile

COPD

New or increased cough and purulent sputum production

Afebrile

No COPD

New cough with purulent sputum and one of the following: respiratory rate >25 breaths/minute or delirium

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection

Categories

Minimum Criteria

Applies to intact skin, devices, or ulcers

Fever or new or increasing redness, tenderness, warmth or swelling at the affected site***

Fever/Focus Unknown

Minimum Criteria

Fever and one of the following: new onset delirium or rigors

Antibiotic resistance

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Prevalence and impact

Pathophysiology and risk factors

Differential diagnosis, assessment, and management

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Symptomatic UTI

Management and treatment

Asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Uncomplicated UTI.

Cystitis

Pyelonephritis

Able to tolerate medication

Absence of:

Obtain a urine culture

Hospitalized—give IV dose initially

First-Line Oral Treatment Options

First-Line Oral Treatment Options

Nitrofurantoin 100 mg bid × 5 days*

TMP/SMZ DS bid × 3 days

(avoid if prior UTI in 3 months, or 20% resistance to sulfas in the community)

Fosfomycin 3 gm single dose*

(lower efficacy)

Pivmecillinam 400 mg bid × 5 days*

(lower efficacy)

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid × 7 days

Levofloxacin 750 mg qd × 7 days

TMP/SMZ DS bid × 14 days

Beta-lactam 10-14 days (less efficacious)

Quinolones

Complicated UTI.

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI)

Prevalence and impact

Pathophysiology and risk factors

Infectious diseases