Chapter 7

Infection and sepsis

Introduction

At least 1 in 10 deaths in the older population are caused by infectious disease. Susceptibility to infection increases due to changes in the immune system, exposure to pathogens in hospitals and care institutions, frailty and decreased physiological reserve. Infection often presents with a change in mental and functional status rather than signs of localised infection. This diagnostic challenge sometimes necessitates empirical treatment, because delayed antibiotic therapy is associated with a higher risk of systemic sepsis, multi-organ dysfunction and death. However, inappropriate antibiotics in the older adult are associated with drug side effects, drug interactions, antibiotic resistance and Clostridium difficile infection.

Background

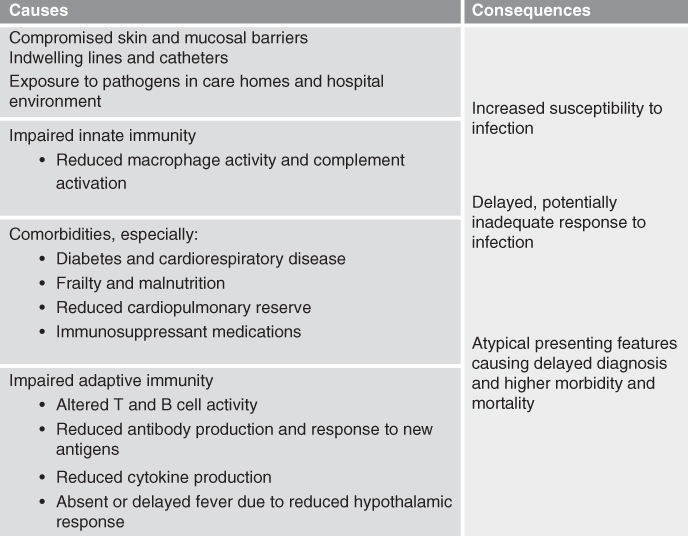

Immunosenescence describes the changes in the ageing immune system that contribute to an increased risk of infection (Figure 7.1). These changes lead to atypical presenting signs and symptoms, delayed or absent fever, delayed or absent rise in inflammatory markers such as white cell count (WCC) or CRP (C-reactive protein) and reduced effectiveness of treatment (1). Impaired adaptive immunity predisposes to the reactivation of tuberculosis or herpes zoster. Vaccination may be less effective in the older adult due to impaired ability to respond to foreign antigens.

Figure 7.1 Immunosenescence in the older person.

Specific causes of infection

The commonest infections in the older person are urinary tract infections, pneumonia and cellulitis, and these will be addressed specifically in this chapter.

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

UTI is the most frequent infection in the older adult. It is also the commonest hospital-acquired infection, often associated with urinary catheters (2). A number of factors predispose to the development of UTI in the older adult (Box 7.1). UTI may be mistakenly diagnosed in 40% of hospitalised older patients (3), due to the high incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Lower urinary tract infections

Lower urinary tract infections include infection of the bladder (cystitis) or prostate (prostatitis).

Upper urinary tract infections

Upper urinary tract infections affect the kidneys (pyelonephritis) or ureters and are more often associated with systemic illness.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria refers to a positive urine culture in a patient without symptoms suggestive of UTI. It represents colonization of the urinary tract rather than infection and occurs in approximately 20% of women and 10% of men over 80, rising to 40–50% of older adults in care institutions (5). Asymptomatic bacteriuria is a risk factor for subsequent development of a UTI, but there is no evidence that prophylactic treatment with antibiotics is of benefit.

An attempt must be made to distinguish asymptomatic bacteriuria from active infection in the older patient, to avoid the complications of unnecessary antibiotic therapy.

Older adults who are hospitalised or in care homes, in particular those with indwelling urinary catheters, are more prone to UTIs from pseudomonas, gram-positive organisms and antibiotic-resistant bacteria including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia Coli. Fungal infections with candida species may also occur.

Respiratory tract infections

Respiratory tract infections are the seventh leading cause of death in the United States (7). Risk factors include increasing age, alcohol excess, chronic respiratory or cardiac disease, reduced mobility and neuromuscular weakness. Residents of long-term care facilities are at particularly high risk.

Pneumonia is the presence of symptoms and signs consistent with acute lower respiratory tract infection, in association with new consolidation visible on chest radiograph (8).

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the commonest cause of community-acquired pneumonia, accounting for over 50% of cases in the older person (9). Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and respiratory viruses make up the majority of other cases. Gram-negative bacilli predominate in patients in hospital and care homes, and in those with comorbid respiratory disease and recent antibiotic use. Patients at risk of aspirating oropharyngeal or gastric contents due to swallowing difficulties, reduced conscious level (commonly seen in the context of delirium or stroke) or impaired mobility may develop pneumonia due to anaerobes or gram-negative organisms.

Influenza is a contagious viral respiratory tract infection caused by influenza A, B or C virus. Outbreaks of influenza are common in care homes and hospitals during the winter months. Most infected persons experience a self-limiting febrile illness with myalgia, headache and fatigue. However, in the older adult, it is frequently complicated by superimposed bacterial infection, often Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae or H. influenzae, leading to higher morbidity and mortality (10).

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is an infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. It commonly affects the lower leg in the older patient, where chronic ulcers, tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) and other wounds can provide a route of entry for bacteria. The majority of cases are caused by Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. In the presence of chronic ulceration or pressure sores, organisms such as MRSA and Pseudomonas may be involved.

Initial assessment

Sepsis

Sepsis is defined as the presence (probable or confirmed) of infection together with one or more systemic manifestations of infection such as tachycardia, tachypnoea, altered temperature or raised WCC or CRP (11).

Assessment of the older patient with potential sepsis should begin with a rapid survey with the aim of identifying any life-threatening features requiring immediate intervention (Box 7.2). In addition, it is important to determine the patient’s goals of care promptly so that the patient does not receive unwanted or inappropriate treatments (Chapter 3).

In suspected sepsis, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given urgently, following blood cultures if possible. In the presence of severe sepsis, each hour delay in administration of effective antibiotics increases mortality (11). In suspected influenza, anti-viral agents should be given within the first 48 hours of the illness to those over 65 years old, and have been shown to reduce severity and duration of the illness (13). Local guidance on antibiotic choice and anti-viral therapy should be referred to.

A more detailed history and examination can take place following the primary assessment and initial treatment.

History

Infection in older adults may present with delirium, falls and reduced mobility, fatigue, vomiting, anorexia and lethargy, rather than specific complaints.

It is important to identify medications in the drug history which may interact with planned antibiotic therapy, particularly those with a narrow therapeutic window such as warfarin, digoxin or phenytoin.

In suspected urinary tract infection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree