and Paul Telfer2

(1)

Department of Haematology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

(2)

Department of Haematology, Royal London Hospital, London, UK

Introduction

Infection is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in SCD. This is partly due to loss of the normal protective function of the spleen, which contributes to the control of invasive infection by removing foreign particles and damaged blood cells from the circulation. Splenic function is also necessary for generating a normal immunoglobulin response to some infections. Hyposplenia in infants is associated with a deficiency in the IgM response to encapsulated bacteria which further increases the risk of invasive infection. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitides, Hemophilus influenzae type b, salmonella species and gram negative enteric organisms can all cause serious systemic infection. Prior to the introduction of pneumococcal prophylaxis, invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) was the most common cause of death in SCD. Infection can progress rapidly causing shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation and adrenal hemorrhage. Children below the age of 2 with HbSS are at highest risk of overwhelming IPD.

There is also an increased risk of gram negative bacterial infection affecting the urinary tract and biliary system, as well as non-typhi salmonella infection causing generalized sepsis and osteomyelitis. These are described in more detail in the Chapters 8, 9 and 12 which cover the relevant organs and systems. Acute chest syndrome and other acute vaso-occlusive crises can be provoked by viral infections of the respiratory tract and ‘atypical’ organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae.

Malaria

Carriers of sickle cell (HbAS) are protected against severe, life-threatening falciparum malaria because intra-erythrocytic HbS impairs parasitic invasion of erythrocytes, inhibits multiplication of parasites and enhances parasitic clearance in the spleen. This resistance to malaria is not apparent in HbSS or other sickle genotypes, and malarial infection in SCD is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. In malarial-endemic countries, children with SCD who present with severe anemia may have co-existent malaria. Long-term malarial prophylaxis has been shown to decrease the rate of severe anemia, sickle crises and to reduce mortality. Patients with SCD travelling to countries where there is a risk of malaria should be advised to take anti-malarial prophylaxis following the current standard recommendations for drug therapy applicable to the part of the world where they are travelling.

Invasive Pneumococcal Disease (IPD)

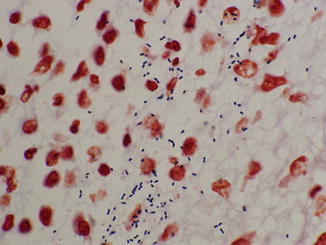

Pneumococcus is another name for the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae. The infections included in the term IPD are pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia. Another common site for pneumococcal infection is the middle ear (otitis media), though this is not classified as IPD. Asymptomatic carriage of pneumococcus in the throat and nasopharynx is common in infants, but does not usually result in IPD. It is important to make a definitive microbiological diagnosis of pneumococcal infection, but this can be difficult in practice. Sputum is often unobtainable in the early stages of pneumococcal pneumonia, and it is challenging to obtain positive cultures from sputum, blood or cerebrospinal fluid because of the need for special culture conditions and meticulous laboratory technique. Sometimes the infection is diagnosed on post-mortem tissue by gram stain (Figure 12.1). Other microbiological techniques include assay for urinary pneumococcal antigen (which is not specific to IPD and may also be positive with nasopharyngeal carriage in infants) and bacterial 16s ribosomal DNA analysis of samples from otherwise sterile sites, including cerebrospinal fluid.