16.1 Introduction

Breast-feeding has always been acknowledged as the optimal way to feed an infant, although recommendations regarding practices have changed as more information has become available. Many early studies on the beneficial effects of breast-feeding were seriously flawed in terms of study design, as well as in the definition of breast-feeding. This led to debate as to whether breast-feeding was advantageous in industrialized countries, where hygiene conditions significantly reduced the incidence of infectious diseases. The discovery that the advantages of breast-feeding are dose related has led to more thorough definitions of breast-feeding patterns and better controlled studies. In 1991, a joint meeting of international World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) representatives culminated in the Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding, defining optimal infant feeding as exclusive breast-feeding from birth to 4–6 months, and continued into the second year of life, with appropriate complementary foods added at about 6 months. Subsequently, the WHO convened an Expert Panel meeting which reviewed over 3000 research papers and concluded that as a population recommendation, 6 months was the optimum age for exclusive breastfeeding. This was then adopted as a World Health Assembly Resolution in May 2001.

Recent evidence has shown that the benefits of breast-feeding over formula feeding are also obvious even in developed countries where there is presumably good access to clean water and sufficient resources to make up formula safely.

- In the UK, low birth weight (LBW) infants in particular have been found to benefit from breast milk, where formula feeding has been found to increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis by a factor of at least six-fold.

- In Scotland, long-term benefits for children 7 years of age, who were exclusively breast-fed for at least 15 weeks from birth, included a significantly reduced probability of ever having a respiratory infection or wheeze, and a lower systolic blood pressure.

- Swedish infants who were formula fed have been found to have significantly higher risk of otitis media in the first year of life compared with predominantly breast-fed infants.

- Swedish preschool infants who were breast-fed for less than 13 weeks were found to have a significantly increased risk of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis, the risk decreasing with every additional week of exclusive breast-feeding.

- In America, formula-fed infants faced double the risk of diarrheal disease and 19% more otitis media in the first year of life, compared with fully breastfed infants.

- Not only does breast-feeding influence health in infancy and early childhood, but it also appears to have long-term benefits, reducing the incidence of asthma in 6-year-old children from Australia.

It is now becoming clear that not all breast-feeding is equal in terms of health outcomes in the infant and that exclusive breast-feeding carries significant advantages over mixed breast-feeding. There are examples of this from around the world.

- In the Gambia, children who were given prelacteal feeds were 3.38 times more likely to die.

- Similarly, in Peru, infant mortality was associated with mixed breast-feeding as well as with never having been breast-fed.

- In Latin America, it has been estimated that 13.9% of all infant deaths could be prevented by exclusive breast-feeding, translating into 52 000 preventable deaths for that area.

This chapter discusses the importance of breastfeeding, reviews trends of infant feeding in different countries over the past century, particularly in relation to socioeconomic status and includes the challenges to optimum breast-feeding. Consideration will be given to breast-feeding difficulties and in particular the issues around breast-feeding by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected women. Finally, infant feeding after 6 months will be discussed, as well as the importance of monitoring the child’s growth in the first few years.

16.2 Role and importance of breast-feeding

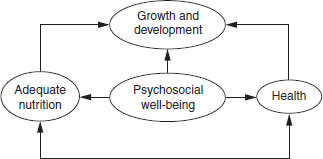

The goal of good nutrition is adequate growth and development. It is well known that this depends not only on adequate dietary intake but also on psychosocial well-being and health (Figure 16.1). Breast-feeding is thus a unique practice, which offers not only adequate nutrient and energy intake, but also psychosocial care through bonding with the mother and health through the immunological properties of breast milk. Breastfeeding in the first 6 months is the one time when infants of rich and poor mothers are on equal footing, as mentioned by James Grant, a past director of UNICEF (Box 16.1).

Several factors affect lactation in a positive and a negative way. These include environmental, psychological and pharmacological factors, and are summarized in Table 16.1.

Advantages of breast-feeding

Human milk is constituted to provide all of the infant’s nutrient requirements for a period of about 6 months, except if the mother is severely malnourished. The composition of the milk changes in line with the infant’s requirements.

Figure 16.1 Adapted UNICEF framework describing the interdependence of nutrition, psychosocial well-being and health to promote the growth and development of a child.

The presence of antibodies and macrophages in the colostrum and breast milk confers protection against certain infections (Table 16.2). Immunity against enteral, and to a lesser extent parenteral infections, is derived from the antibodies. As a result it is uncommon for a fully breast-fed infant to contract infective diarrhea or necrotizing enterocolitis. Respiratory and ear infections also occur less frequently in breast-fed babies.

The incidence of allergies in infants who are breast-fed is decreased compared with those who have been fed cow’s milk. The delayed introduction of foreign proteins may also be beneficial in reducing the chances of developing autoimmune reactions such as occur in the development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Table 16.1 Factors affecting lactation

| Favorable | Unfavorable | |

| Environment | Calm, relaxed | Noisy, stressful |

| Frequency of feeds | Frequent | Infrequent |

| Breast contents | Engorged | |

| Emotional state | Relaxed | Anxious |

| Physical state | Comfortable | Pain, tense |

| Drugs | Metoclopramide | Estrogen |

| Oxytocin (sublingual) | Testosterone | |

| Bromocriptine | ||

| Sedatives (large doses) |

The incidence of sudden infant death syndrome is lower in breast-fed babies, although the reason for this is not clear.

Breast milk is hygienic, inexpensive, convenient and readily available for the infant. It requires no preparation or sterilization. These factors are likely to outweigh the possible disadvantages of restricted activities or temporary unemployment for the mother and therefore need serious consideration. Breast-feeding is less expensive than any substitute, even if the mother has to eat slightly more. An additional factor to consider is that the breast-fed infant’s ration does not have to be shared by other members of the family.

One study found that significantly higher scores for cognitive development were associated with breast-fed children compared with those who were formula fed. This effect was sustained until 15 years of age and those breast-fed for the longest showed the most difference. (see Chapter 15). Breast-feeding strengthens the psychological bonding process between mother and child. There is anecdotal evidence that this is especially important in the later development of the child’s personality and in the socialization of the child. Ovulation is suppressed by demand breast-feeding. Decreased fertility due to lactational amenorrhea, associated with regular continued breast-feeding, differs between individual women, but may continue for 12 months or longer. This should not be considered a reliable method of contraception, as 3–7% of breast-feeding women do become pregnant. The relative risks of disease in formula-fed infants are summarized in Table 16.3.

Table 16.2 Immune factors in breast milk

| Immune factor | Functions |

| B-lymphocytes | Give rise to antibodies targeted at specific microbes |

| Macrophages | Kill microbes in the infant’s gut; produce lysozyme; activate other components of the immune system |

| Neutrophils | Ingest bacteria in the infant’s gut |

| T-lymphocytes | Kill infected cells, send chemical messages to mobilize other defences |

| Immunoglobulin A antibodies | Bind to microbes in the infant’s gut, preventing them from passing through the mucosa |

| B12 binding protein | Binds B12, preventing use by bacteria for growth |

| Bifidus factor | Promotes growth of Lactobacillus bifidus |

| Fatty acids | Disrupt membranes surrounding certain viruses, destroying them |

| Fibronectin | Increases antimicrobial activity of macrophages; facilitates repair of damaged tissues |

| Gamma-interferon | Enhances antimicrobial activity of immune cells |

| Hormones and epithelial growth factor | Stimulate epithelial maturation, reducing vulnerability to microorganisms |

| Lactoferrin | Binds iron, reducing availability for bacteria |

| Lysozyme | Kills bacteria by disrupting cell walls |

| Mucins | Adhere to bacteria and viruses, preventing attachment to mucosa |

| Oligosaccharides | Adhere to microorganisms, preventing attachment to mucosa |

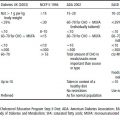

Table 16.3 Relative risks of disease in formula-fed infants highlighted by individual studies

| Diarrhea | In Brazil, formula-fed infants are 14.2 times more likely to die from diarrhea than breast-fed babies |

| Ear infection | Formula-fed infants have twice the number of ear infections of exclusively breast-fed infants |

| Bacterial infections | In the USA, formula-fed infants are 10 times more likely to be admitted to hospital for any bacterial infection, and four times more likely to have meningitis |

| Cancer | Formula-fed infants are twice as likely to develop cancer by 15 years of age compared with breast-fed infants |

| Sudden infant death syndrome | Formula-fed infants are almost three times more likely to die from sudden infant death syndrome than breast-fed infants |

| Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | These diseases are more common in formula-fed infants |

| Eyesight | Formula-fed infants have poorer vision at 4 and 36 months compared with breast-fed infants |

| Pneumonia | In Brazil, infants fed only formula milk were 3.9 times more likely to die from pneumonia than breast-fed infants |

| Urinary tract infections | Formula-fed infants are five times more likely to contract urinary tract infections than breast-fed infants |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | Infants born at 30 weeks of gestation, who are formula fed, are 20 times more likely to develop necrotizing enterocolitis |

| Diabetes | Infants who are formula fed before 2 months of age are twice as likely to develop diabetes |

| Celiac disease | Formula-fed infants show accelerated development of celiac disease |

| Dental caries | Children who have been formula fed have more dental caries than breast-fed children |

| Cognitive development | Formula-fed infants show lower scores on mental ability tests |

Table 16.4 Relative risks of not breast-feeding for the mother highlighted by individual studies

| Breast cancer | Women who have not breast-fed for at least 3 months have double the risk of developing premenopausal breast cancer |

| Child spacing | Formula feeding increases the risk of a second pregnancy, which adversely affects the mother’s health |

| Ovarian cancer | Women who have not breast-fed for at least 2 months per child have a 25% increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer |

| Osteoporosis | The risk of hip fracture is doubled in women over 65 if they have never breast-fed |

Breast and ovarian cancer occurs less frequently in women who have breast-fed. The relative risks of not breast-feeding to the mother are summarized in Table 16.4.

Researchers have not always used the same definitions of breast-feeding, making comparisons of different studies difficult. To standardize research, and thereby obtain a better understanding of the benefits of breast-feeding, the definitions now used are summarized in Box 16.2.

Secular trends in infant feeding

In the 1920s, breast-feeding rates began to decline rapidly in industrialized countries, from approximately 50–70% of newborns breast-feeding on discharge from hospital, to the 1970s, where only 10–25% of newborns were breast-fed in the first week of life. This decline was associated with the increased availability of infant formulas, the aggressive marketing of replacement formula and the introduction of many conveniences associated with formula feeding. Since the 1970s, there have been many programs aimed at increasing the rate of breast-feeding.

At the beginning of the decline, disadvantaged mothers were more likely to breast-feed than advantaged mothers. Advantaged mothers, with a higher educational level, led the decline, but subsequently also led the upward trend. The increase in breast-feeding among disadvantaged women has been much slower. In the USA, the mother least likely to breast-feed is a young African–American, with no college education, living in a rural area, who has an LBW infant: possibly the infant who would most benefit from breast-feeding. Similar findings from the UK, where inner-city mothers, with less than 18 years of education, delivering at the hospital with the regional neonatal high-care unit, experienced the sharpest decline in breast-feeding between 1979 and 1988. In the Philippines, delivering in a hospital was associated with a significantly lower incidence of breast-feeding.

Wide differences exist in breastfeeding initiation and duration both between and within developed countries. For example, in Europe, rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months vary from as much as 46% in Austria and 42% in Sweden to 21% in the UK and 10% in Germany. However, it should be noted that data on exclusive breast-feeding are scarce and unavailable in many countries. Reliable surveillance systems across Europe using a common harmonized methodology need to be developed. In addition to this intercountry variability in breast-feeding rates, wide within-country differences exist. A strong relationship between duration of breast-feeding and socioeconomic status has been shown, with a pattern of shorter duration of breastfeeding among lower social classes. For example, in the UK 48% of women from the highest social class were still breast-feeding at 6 months compared with just 22% from the lowest social class.

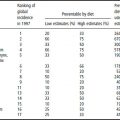

Because of this association between breast-feeding (initiation and duration) and social class, it is important when examining the relationship between breastfeeding and childhood morbidity that social class is controlled for in the analyses. This is generally done through stratification of the data or through the use of multivariate analysis. While most studies correct for social status, few studies actually represent the differences in morbidity for different socioeconomic levels. An example of this may be seen in a study examining the impact of breast-feeding on admission for pneumonia during the postneonatal period in Brazil. The study found that infants who were not being breast-fed were 17 times more likely than those being breast-fed to be admitted to hospital for pneumonia. Since social class was associated both with the outcome (admission to hospital for pneumonia) and the variable of interest (feeding method) it was controlled for in this multivariate analysis. Table 16.5 outlines the risk for admission to hospital for pneumonia according to socioeconomic status (defined in this study by economic status). The higher social classes (professionals and owners of large businesses) had the lowest risk for admisssion to hospital, while the lowest category of social class (unemployed/casual workers) had the highest risk for hospital admission.

Table 16.5 Risk of hospitalization for pneumonia according to socioeconomic status in Brazil

| Social class represented by employment | Odds ratio |

| Professionals large business owners | 0.2 |

| Small business owners and shopkeepers | 1.49 |

| Nonmanual, regularly employed | 1 |

| Manual, regularly employed | 1.78 |

| Unemployed/casual workers | 3.5 |

Reproduced from Cesar (1999) with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group. The lower the odds ratio, the less protective effect breast-feeding has on the risk of diarrhea.

In developing countries, the effect of socioeconomic status is reversed. More affluent mothers with a higher level of education are less likely to breast-feed. An inverse relationship has been found between maternal education and the mean duration of breast-feeding. Again, a strong inverse relationship was found between births attended by health-care workers and mean duration of breast-feeding.

While breast-feeding rates are increasing in many developed countries, the decline in breast-feeding is still obvious in the developing countries, especially in urbanized areas. Various scenarios operate to perpetuate this situation. Artificial feeding is regarded as a status symbol by many, partly because of the marketing of breast-milk substitutes, and partly because replacement feeding has been commonly practiced by affluent women. Working mothers frequently have to leave their babies in the care of others and institute cessation of breast-feeding very early. This is often due to a lack of, or inadequate facilities at their place of work which, if available, would allow mothers to continue to breast-feed. Many of these mothers are unaware of how to maintain lactation.

16.3 Barriers to successful breast-feeding

Many unsubstantiated beliefs and attitudes about breast-feeding mean that mothers may not choose to breast-feed exclusively in the first 6 months. Common reasons why mothers do not breast-feed exclusively include:

- mother’s unfounded fear that the milk is insufficient and/or of poor quality

- delay in initiating breast-feeding, and discarding colostrum

- poor breast-feeding technique

- mistaken belief that infants become thirsty and need extra fluid

- lack of support from the health services

- marketing of breast-milk substitutes.

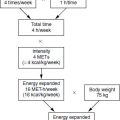

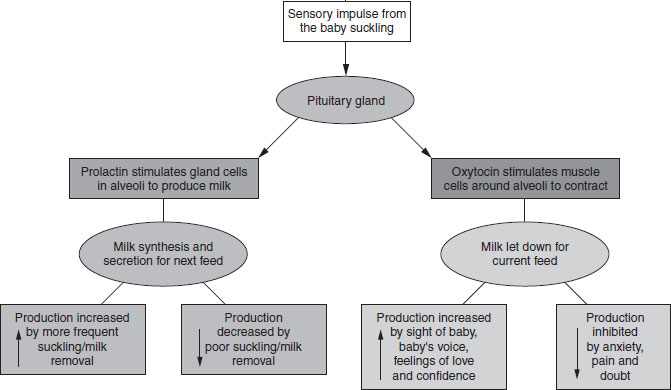

Figure 16.2 Hormonal control of lactation.

Mother’s unfounded fear that the milk is insufficient and/or of poor quality

This can be linked to the appearance of the foremilk, which is thin and watery. The mother needs to understand that changes in milk composition occur with suckling. The foremilk is thin and watery, but high in protein and antibodies. The foremilk will satisfy the infant’s thirst, while the hindmilk, rich in fat, will satisfy the infant’s hunger.

Breast-milk quantity can be kept up by frequent suckling at the breast. Hormonal control of breast-milk production is represented in Figure 16.2. Breast-milk production cannot be increased by dietary changes. The relatively small stools of the breast-fed infant are due to the minimal amount of indigestible material present in the milk and the stools of exclusively breast-fed infants are normally loose and yellow. The mother should be reassured and supported to continue breast-feeding as long as the infant is gaining at least 500 g per month, appears satisfied and passes a normal amount of urine (approximately six to eight wet nappies per day or a wet nappy after each feed, provided the infant does not receive any fluid other than breast milk).

Delay in initiating breast-feeding, and discarding colostrum

In many developing communities traditional beliefs are firmly entrenched and colostrum may be regarded as poisonous, or it may be felt that affliction or bewitchment can occur through breast milk. Such traditional beliefs have to be handled tactfully and with discretion. Mothers who initiate breast-feeding early are more likely to breast-feed exclusively, and breast-feed for longer.

Poor breast-feeding technique

Breast-feeding is a learned art. Both mother and infant need to learn how to breast-feed successfully. If the infant is not well attached or appropriately positioned, the mother is likely to experience nipple pain, nipple fissures, and possibly engorgement and mastitis as the infant may not effectively remove milk from the breast. This is likely to lead to cessation of breast-feeding.

The 10 points for successful breast-feeding are summarized in Box 16.3. For comfortable, relaxed breastfeeding, the mother should lean on a backrest and hold the baby securely in her arms. The infant should face the mother, with the infant’s whole body turned towards the mother, and the buttocks should be well supported. Head and body should be straight. The infant should be brought up to the mother’s breast. For the infant to be well attached, the mouth should be wide open, with more areola visible above the mouth than below, the lower lip should be turned out and the infant’s chin should be touching the breast (Figure 16.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree