Small lymphocytic lymphoma/ chronic lymphocytic leukemia

B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma

Hairy cell leukemia

Splenic B–cell lymphoma/leukemia unclassifiable a

Splenic red pulp small B–cell lymphoma a

Hairy cell leukemia–variant a

Lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma

Waldenström macroglobulinemia

Heavy chain diseases

Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma

Pediatric nodal marginal zone lymphoma a

Follicular lymphoma

Pediatric follicular lymphoma a

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma

Follicular lymphoma, hairy cell leukaemia and mantle cell lymphoma are mainly diagnosed in the age between 50 and 69 years. Over half of the patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, immunoproliferative diseases, plasma cell neoplasms, and B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia are 70 years or older [5].

Although the incidence of lymphoid neoplasms decreased at the rate of 1 % per year among males during 1992–2001, there was an increase of follicular lymphoma at 1.8 % per year in senior people at the same time [6]. Marginal zone lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma also increased in number in this time period, but to a lesser extent, being most likely due to improved diagnostic tools in these entities [6].

In general, advanced age is associated with an inferior prognosis and shorter survival in lymphoma, particularly beyond the age of 50 [3]. This also holds true for indolent lymphoma, but not to that extent observed in patients with precursor cell neoplasms, classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma or Burkitt lymphoma [3].

The precise mechanisms, underlying the high incidence of indolent lymphomas in elderly patients, are not known. Of note, e.g. monoclonal gammopathy of unknown origin, which may precede to multiple myeloma, is rare in younger people, but occurs in 5.3 % of the population at ≥70 years old and in 7.5 % among those 85 years of age or older [7]. In a similar way, monoclonal B-lymphocytosis, which may precede to chronic lymphocytic leukemia is also associated with advanced age [8].

Age Associated Variants of Indolent Lymphomas

Usually, most indolent lymphomas are diagnosed beyond 50 years of age. However, in follicular lymphoma, a “pediatric” variant is described which occurs in patients under 40 years [9]. This variant is often localized (stage I), has a high proliferation rate (Ki-67 >30 %) and lacks a BCL2 rearrangement. This particular subset, which is otherwise morphologically not different form the “adult form”, is highly indolent and does not progress or relapse. On the other hand, younger patient with typical BCL2 rearranged and advanced follicular lymphoma have an outcome comparable to elderly patients. In a similar way, the pediatric nodal marginal zone lymphoma (nMZL) was included as a provisory entity into the WHO classification. There is a male predominance (rate 20: 1) and as in pediatric FL, the disease is localized (usually head and neck lymph nodes), asymptomatic and extremely indolent [10].

Whereas pediatric FL and nMZL seem to be distinct entities with biological and clinical characteristics setting them apart from the variants at the advanced age, there are not much data about biologic differences within the age groups from 60 to 79 years versus ≥80 years of age. In general, patients ≥80 years old have a poorer performance status (PS 2–4 in 37 % in contrast to 20 % in patients between 60 and 79 years), more often B symptoms and renal failure, resulting in a slightly poorer age-adjusted International Prognostic Index (IPI) [11]. Most other risk factors are distributed equally.

The Best Starting Point for Treatment

It is generally accepted, that a careful “watch and wait” strategy is standard of care – even in younger patients – until clinical symptoms (e.g. fever, night sweat, loss in weight, local compression or hematopoietic failure) occur (Table 8.2). This approach is supported by a randomized study of the “British National Lymphoma Investigation”(BNLI) [12], providing data with a median observation time of 16 years: 309 patients were randomized either to chlorambucil or a watch and wait strategy. There was no survival benefit for one of the patient groups. Moreover, 20 % of patients did not receive any chemotherapy during the observation time. Particularly in elderly patients, this approach is appropriate since only 40 % of the patients older than 70 years required systemic treatment. A second randomized study, comparing prednimustine, interferon-γ and “watch and wait”, also did not show any survival benefit for immediate treatment [13].

Table 8.2

International criteria for treatment start in follicular lymphoma

GELF criteria [13] |

|---|

One or more of the following criteria: |

Tumor > 7 cm in diameter |

3 nodes in 3 distinct areas each > 3 cm in diameter |

Symptomatic spleen enlargement |

Organ compression |

Ascites or pleura effusion |

Presence of systemic symptoms |

No leukemia |

No peripheral blood cytopenia |

Since more effective and importantly less toxic treatments than chlorambucil were established in the last two decades, the value of “watch and wait” is still under discussion. Particularly the monoclonal antibody rituximab, which targets CD20 – positive B – cell lymphoma cells, provides a non – toxic treatment option which is effective as monotherapy in indolent lymphomas [14]. The combination of anti-lymphoma activity with a favourable toxicity profile makes this compound highly attractive for the group of elderly patients. In a recent clinical trial of the BNLI, “watch and wait” was randomized against a monotherapy with rituximab (4 weeks induction, or 4 weeks followed by a maintenance therapy every 2 months over 2 years). The time to initiation of a new chemotherapy was much longer in the rituximab arm compared to “watch and wait”. As expected, there was no significant survival benefit in all three arms after a median observation time of 3 years. In a recent non – randomized study, there was no significant difference in the freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) between patients with low tumor burden treated either with watch and wait or rituximab monotherapy [15]. Thus, although rituximab single agent therapy is effective and well tolerated first line, there are no data showing that immediate treatment with rituximab is superior to the traditional watch & wait approach. In conclusion “watch and wait” remains the most useful and cost-effective strategy, particularly in elderly patients.

Diagnostic Standards

Since therapy is guided by clinical symptoms particularly in elderly patients, medical history and physical examination is very important to guide the management of patients with indolent lymphoma. Standard laboratory analysis should contain blood count and hemogram, as well as lactate dehydrogenase. At initial diagnosis, serum immunoglobulins, immunofixation, ß2-microglobulin and serologic evaluation of HIV-, HBV- and HCV- status are recommended. Imaging studies can be used conservatively, in many cases ultrasound and conventional chest X-ray is adequate, particularly in asymptomatic patients. The intervals of examinations widely vary depending on the clinical course of the disease (every 3 months after diagnosis up to 6 months in stable patients).

Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients

Since indolent lymphomas are usually generalized at diagnosis, systemic treatment is generally preferred over local radiotherapy. However, in rare cases of localized involvement, involved-field radiotherapy is considered as standard of care according to international guidelines [16] offering the chance for a cure from lymphoma. Due to the long-term side effects of radiotherapy and the improved outcome in indolent lymphoma with systemic treatment, there may be a paradigm change in the next years, favouring mild non-toxic treatment such as rituximab single agent therapy over radiotherapy. In the prospective LYMPHOCARE registry, patients treated with systemic treatment had a significant longer progression free survival than patients with radiotherapy; there was no significant difference between patients with involved field irradiation and “watch and wait” [17]. Patients which refused radiotherapy had also an excellent long term outcome [18].

In contrast to other indolent lymphomas, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma is often localized, therefore radiotherapy is considered as standard in many cases. However, since these lymphomas have an excellent prognosis in most cases, e.g. can be successfully treated by eradication of a bacterial trigger or by treatment of an autoimmune condition, it is reasonable to abstain from radiotherapy in many elderly patients: an example for this is the localized extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the stomach, which persists 12 months after antibacterial eradication therapy and has an excellent long – term outcome even without radiotherapy [19]. Finally, rituximab monotherapy can replace local radiotherapy in patients with need of treatment at least in several subsets of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma [20, 21]. Thus, in particular in elderly patients a watch & wait strategy or rituximab single agent might be considered as an alternative to radiotherapy. On the other hand, radiotherapy may be a useful treatment option in elderly patients with advanced and relapsed indolent lymphoma. A low-dose involved field irradiation (2 × 2 Gy in 4 doses, in 2 days) often provides an excellent long – term control of tumor bulk, otherwise causing local complications, and may be an ideal option for elderly patients [22].

Systemic Treatment in Elderly Patients

In the last decades, the treatment goals in younger patients with indolent lymphoma changed from supportive treatment in order to control symptoms to induction of a complete (molecular) remission as a surrogate marker for the longest progression free survival possible. Although in elderly or frail patients, the control of symptoms is still the main objective of treatment, high response rates and long progression free survival can also be achieved in this often co-morbid patient population, using new targeted treatment strategies.

An example of a targeted treatment strategy, which has dramatically changed the perspective of many patients with different types of B-cell lymphomas is the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody Rituximab: rituximab monotherapy induces high response rate in relapsed patients (46 %) and even higher in untreated patients (67 %), which are in need of treatment [23]. The event-free survival differs from 13 months in pretreated up to 33 months in treatment naïve patients [24]. Therefore, rituximab monotherapy is an attractive treatment option in elderly patients. However, it is not approved as monotherapy in first line treatment, and may be insufficient in patients with tumor bulk or need for rapid remission. Nevertheless, rituximab monotherapy is the preferred first-line treatment in elderly patients not qualifying for chemoimmunotherapy according to the NCCN guidelines in North America [25].

In medically fit patients the standard approach is to combine rituximab with conventional cytostatic drugs. The most frequently used regimen in North America is R-CVP (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine and Prednisolone) and R-CHOP (additionally Doxorubicin), whereas in Europe R-CHOP but also increasingly R – Bendamustine belongs to the most popular regimens. In elderly patients, the use of R-CHOP is limited by the neurotoxicity of vincristine, the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicine and a higher rate of febrile neutropenias. In elderly patients, qualifying for immunochemotherapy alternative schedules are more appropriate such as R – Bendamustine, R-MCP (Rituximab Mitoxantrone, Chlorambucil, Prednisolone) or R-Chlorambucil. R-MCP has shown an excellent progression free survival in patients with indolent lymphoma, but is stem cell toxic. Therefore, it is particularly appropriate for elderly patients, which are not eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation [26]. In two recent randomized clinical trials R-CVP was inferior to R-CHOP, so that R-CHOP is a valid treatment option in elderly fit patients. In the same trials fludarabine containing regimens showed a higher toxicity compared to the other arms [27, 28]. This is in line with the results of randomized clinical trials reporting a higher toxicity and survival disadvantage in elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma [29] or chronic lymphocytic leukemia [30]. Therefore, fludarabine containing combinations (e.g. R-FC rituximab-fludarabine- cyclophosphamide or R-FM rituximab-fludarabine-mitoxantrone) should be applied with caution in elderly patients, particularly in patients with a compromised renal function.

Bendamustin was first synthesized in 1963 in East Germany and available not before 1990 in Western countries. In a randomized clinical trial, R-Bendamustin was compared with standard R-CHOP. Although initially designed to shown non-inferiority of R – Bendamustine compared to R-CHOP, this study surprisingly demonstrated a higher response rate and a impressive longer progression free survival (69.5 versus 31.2 months, hazard ratio 0.58, 95 % CI 0.44–0.74; p < 0.001) for R – Bendamustine [31, 32]. Since Bendamustin has less toxic side-effects (e.g. no alopecia, less neutropenia and febrile neutropenia), it can probably be considered as one of the most acceptable chemoimmunotherapies in elderly patients, at least in the “go-go” and parts of the “slow-go” subgroup.

Another appealing concept in the treatment of B – cell lymphomas is radioimmunotherapy, exploiting the high radiosensitivity of lymphomas and minimizing non – targeted irradiation. In this line the conjugation of a ß-emitting radioactive particle to a monoclonal antibody against B-cell antigens provides an elegant way to deliver radiation to B – cell lymphoma cells. 90Yttrium-ibritumomab (Zevalin®) and 131I-Tositumomab (Bexxar®), which link 90yttrium or 131iodine to an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, are approved in Europe and U.S., respectively. Both drugs are applied as a single infusion treatment and have few non-hematologic side effects. Due to the prolonged myelosuppression which occurs between 4 and 8 weeks after treatment, a close surveillance of the patients is necessary during this period. Despite single application, the remission rates are high – between 74 % in relapsed patients [33] and 95 % in first line patients [34]. Therefore radioimmunotherapy can be considered as an alternative to multiple cycles of chemoimmunotherapy in elderly patients. In the FIT trial consolidation with Zevalin® after a chemotherapy induction provided very high remission rates, even in patients who were treated before with well – tolerable treatments like oral chlorambucil [35]. Another option to improve or at least stabilize treatment outcome of initial induction treatment is a maintenance therapy with Rituximab, which was shown to improve duration of response after immunochemotherapy both in first line and in relapse without major toxicities in large randomized clinical trials. In the meanwhile Rituximab maintenance was approved for follicular lymphoma after chemotherapy induction, characterizing this approach as a highly attractive option to keep elderly patients with follicular lymphoma in remission [36].

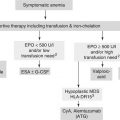

In the group of frail patients (“no-go”), there are still few data available. If in the opinion of the threating physician a chemoimmunotherapy is not feasible, rituximab monotherapy or radioimmunotherapy is recommended at least according the NCCN guidelines [25]. Another option may be the oral alkylating drugs – like chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide or trofosfamide providing control of symptoms in many cases and an objective response rate between 36 % in chlorambucil [37] and 49 % in trofosfamide [38]. However, the combination of oral chlorambucil with rituximab, which may be tolerable in many frail patients, can improve the complete response rate up to 89 % including a 63 % complete response rate in previously untreated patients [39]. In order to control symptoms in very ill patients, low dose prednisolone or dexamethason, low dose irradiation and best supportive care may be appropriate. Table 8.3 summarizes the different treatment options according to the fitness of the patient (Table 8.3).

Table 8.3

Current recommendations for patients falling into different ‘fitness categories’

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree