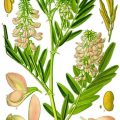

Fig. 2.1

A tentative holistic model of first trimester symptoms and third trimester eating habits

Food-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) values may reflect exposure to specific antigens. The immune system does not recognize food antigens by a strong specificity, as is the case of IgE, but rather by an approach of similarity, reacting to food clusters that can reflect different eating habits of different populations. The excessive and recurrent intake of similar food clusters and the excessive production of corresponding antibodies could start a cause-effect reaction and an increase of inflammatory mediators. This mechanism, together with possible disease evolution, offers the very opportunity to avoid or to modulate the activation of inflammatory response.

2.2 Hormones and Cytokines Cross Talk

If in the past pregnancy was seen exclusively as a process to bring offspring to a stage of maturity sufficient for survival, similar to an incubation process, pregnancy is today interpreted as a complex process that determines the environment of the first stages of development and programs the genomic unfolding of fetal metabolism and its future health in adulthood.

The interaction between the mother and embryo begins with the implantation of blastocyst. The prerequisite of successful implantation depends on achieving appropriate embryo development to the blastocyst stage and at the same time the development of an endometrium that is receptive to the embryo. Implantation is a very intricate process, which is controlled by a number of complex molecules like hormones, cytokines, and growth factors and their cross talk. A network of these molecules plays a crucial role in preparing receptive endometrium and blastocyst [1]. Viviparity has many evolutionary advantages but brings in the problem of the semi-allogeneic fetus having to coexist with the mother for the duration of pregnancy. In species with hemochorial placentation, such as the human species, this problem is particularly evident as fetal trophoblast cells are extensively intermingled with maternal tissue and are directly exposed to maternal blood. Fascinating adaptations on both the fetal side and maternal side have allowed for this interaction to be redirected away from an immune rejection response, not only toward immune tolerance but, in fact, toward actively supporting reproductive success [2]. The implantation of the blastocyst is the result of a balance between inflammation and immune tolerance (Table 2.1). Inflammation-like responses are already induced by sperm and are necessary, or at least beneficial, for implantation [3]. Prominent roles for proinflammatory cytokines in implantation and decidualization have been attributed, for example, to IL-1, IL-6, and IL-11 [1, 4, 5], whereas TNF-alpha seems to have the opposite function in restricting the number of implantation sites. If progesterone is essential for pregnancy maintenance, Erlebacher et al. describe that TNF-alpha-induced inflammation has been shown to inhibit progesterone production in mouse ovaries [6] as well as TNF-alpha-receptor knockout mice have an increased fertility [7] (Fig. 2.2).

Cytokines | Effect on implantation of blastocyst | Description |

|---|---|---|

IL-1 | + | IL-1 stimulates endometrial IL-6 protein production, regulating the activity of this interleukin |

IL-6 | + | The crucial role of IL-6 during implantation is defined using IL-6-deficient mice, which show reduced implantation sites and reduced fertility. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), a member of IL-6 family, is secreted from the uterus, and it is regarded as an important factor in both adhesive and invasive phases of implantation due to its anchoring effect on the trophoblast |

IL-11 | + | The lacking of the receptor of IL-11 brings female mice to infertility for a defective uterine response to implantation |

TNF-alpha | – | TNF-alpha restricts the number of implantation sites, and TNF-alpha-induced inflammation has been shown to inhibit progesterone production in mouse ovaries, and TNF-alpha-receptor knockout mice have an increased fertility |

Fig. 2.2

Pregnancy expresses a balance between tolerance and inflammation with a intertalk between mother and offspring during pregnancy and breastfeeding until weaning. This process determines the environment of the first stages of development and programs the genomic unfolding of fetal metabolism and its future health in adulthood

2.3 A Balance Between Inflammation and Immune Tolerance

In a pregnancy that progresses normally, maternal adaptation to pregnancy occurs, resulting in the maintenance of fetal immune tolerance. The tolerance in pregnancy is the result of a complex network of changes that interest both the innate immune system with the rise of a new decidual natural killer population and adaptive immune system with the generation of CD4+ T reg and CD8+ T suppressor cells which together direct the production of cytokines and immunoglobulin with the aim of inducing tolerance in the maternal immune system. This successful adaptation is reflected by a well-developed immune system and a healthy child after birth [8, 9]. Adverse effects of maternal immune adaptation to pregnancy may result from or be aggravated by exogenous or endogenous threats [10]. Endogenous threats may include low amounts of maternal progesterone [11] and higher maternal age [12], whereas exogenous ones may include stress perception, infections [13] and possibly vitamin D deficiency [14], and last but not least nutritional habits. These threats may result in a failure to maintain fetal immune tolerance and may lead to pregnancy complications, such as infertility, fetal loss, preterm labor, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, and poor fetal development. These complications may adversely affect children’s health and compromise their immunity later in life.

2.4 An Evolutionary Perspective

For a better understanding of how the environment and in particular the diet of pregnant women can influence the process of immune tolerance, it is useful to look at these complex phenomena from an evolutionary perspective. Common symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and cravings in pregnancy could also be interpreted from an evolutionary point of view. Sherman et al. find great support in the hypothesis that normal levels of nausea and vomiting in the first trimester of pregnancy (excluding hyperemesis) protect pregnant women and their embryos from harmful substances in food, particularly pathogenic microorganisms in meat products and toxins in strong-tasting plants [15]. Likewise the cravings in the last trimester of gestation might represent the evolutionary necessity of exposing the fetus to an increasing number of antigens raising immune contact with the outside world so as to provide immune imprinting.

As a matter of fact, recent studies have shown that food-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) values may reflect exposure to a specific antigen [16, 17]. For the fetus, the immune knowledge of the outside world is achieved through the IgG produced by the mother. IgG antibodies cross the placental barrier, and colostrum and breast milk as well are rich in maternal IgG (Fig. 2.2).

IgG antibodies and in particular IgG4 are strictly connected to immune tolerance to food antigens. Protective antibodies have the capacity to modulate the response by preventing allergen binding to surface-bound IgE or inhibiting dendritic cell maturation [18]. IgG4 antibodies differ functionally from other IgG subclasses in their anti-inflammatory activity, which includes a poor ability to induce complement and cell activation because of low affinity for C1q and Fc receptors. In addition, these antibodies do not precipitate antigens owing to their ability to bind different antigens in different places [19].

IgG may be responsible for a process of attenuation of the immune response, but at the same time this class of immunoglobulins is also able to activate inflammatory processes. Studies with mouse models demonstrate two pathways of systemic anaphylaxis and activation of immune response: a classic pathway mediated by IgE, FcεRI, mast cells, histamine, and platelet-activating factor (PAF) and an alternative pathway mediated by total IgG, FcγRIII, macrophages, and PAF [20]. The importance of the alternative pathway in humans is discussed, but human IgG, IgG receptors, macrophages, mediators, and their receptors have appropriate properties to support this pathway if enough IgG and antigens are present [21].

According to this model, an excess of IgG may be responsible for the activation of an immune response even in pregnant women, altering the balance of immune tolerance to the fetus, which is a very delicate process. IgG antibodies express a previous immune contact with food. The production of IgG is linked to the “knowledge” of food and the delicate immune balance that allows alien food antigens to land on the gastrointestinal mucosa, the largest external surface of our body, two hundred times wider than our skin, to be accepted by the cross talk with the immune system and the microbiota. The excessive production of antibodies and the excessive and recurrent intake of food corresponding to these antibodies could overrun this balance and cause a reaction and an increase of inflammatory mediators (Fig. 2.2).

Western supermarket-to-fridge diet is prone to cause this unbalance: excess of refined carbohydrates, excess of long-chain saturated omega-6 fatty acids, excess of cholesterol, excess of proteins from red meat and dairy products, low insufficient consumptions of veggies and fruit, absence or poor consumption of freshly prepared food, absent or insufficient consumption of natural antioxidants and anti-inflammatory spices, iterative quasi-constant food items in the diet, and absence of seasonality in food consumption. All these factors conjure to determine excessive clusters of antibodies against food antigen clusters in parallel with unbalanced composition of the microbiota devoid of natural prebiotic (fibers) environment, whose role might even be overturned from an anti-inflammatory partner of dendritic cells of the intestinal mucosa into an aggressive bunch of proinflammatory bacteria.

2.5 BAFF and PAF, Two Cytokines at the Root of Maternal and Fetal Health

One of the main effectors of the inflammatory pathway supported by an excess of IgG is PAF (platelet-activating factor, also known as PAF-acether or AGEPC (acetyl-glyceryl-ether-phosphorylcholine)). PAF is a potent phospholipid activator and mediator of many immune functions, including platelet aggregation and degranulation, inflammation, and anaphylaxis. It is also active in vascular permeability, the oxidative processes, and chemotaxis.

In the chain of activation of the inflammatory response to IgG for food, it is essential to mention a second proinflammatory cytokine, called BAFF (B-cell-activating factor). BAFF and PAF have already been linked in nonatopic subjects to food reactions [22], and many studies suggest that BAFF could probably be one of the cornerstones of IgG pathway of immune reaction to food. A recent observational study by our group found a highly significant correlation between PAF and BAFF values in all three trimesters of pregnancy [23] in nonobese pregnant women with uneventful pregnancies. BAFF is a member of the TNF superfamily and an important regulator of peripheral B-cell survival and immunoglobulin class-switch recombination.

These properties of PAF and BAFF probably allow the use of any of these two molecules as a marker of inflammation in pregnancy and as a marker of the role of the IgG pathway in immune reaction. These findings are part of a larger research on immune system adaptation in pregnancy and their relation with the production of specific IgG for food, the enteric immune system, and the accelerated inflammation in pregnancy of women at risk of metabolic syndrome.

The excessive production of IgG associated with unbalanced nutrition may eventually generate an increase in low-grade inflammation through the activation of a pathway that involves IgG, PAF, and BAFF, probably. Future investigations should study the possible risks of immune response of the mother against the placenta. These changes in the levels of maternal inflammation may have an influence on the long-term health of the offspring. As mentioned previously, the increased levels of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha reduce the maternal capacity to tolerate the trophoblast invasion and the production of progesterone and its effectiveness in the maintenance of pregnancy.

2.6 The Connection Between IgG for Food and Inflammation

A brief summary of a recent work conducted by our group could help sketch the connection between IgG and inflammatory responses [24, 25]. Specific IgG antibodies against 44 common food antigens were measured in sera of 11,488 Italian patients self-selected for gastrointestinal symptoms related to food reaction. Allergies, that is, IgE-mediated reactions, were not included.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree