Incontinence: Introduction

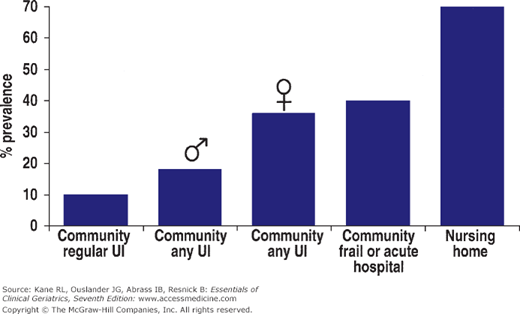

Incontinence is a common, bothersome, and potentially disabling condition in the geriatric population. It is defined as the involuntary loss of urine or stool in sufficient amount or frequency to constitute a social and/or health problem. Figure 8-1 illustrates the prevalence of urinary incontinence across various settings. The prevalence depends on the definition used. Incontinence ranges in severity from occasional episodes of dribbling small amounts of urine to continuous urinary incontinence with concomitant fecal incontinence.

Approximately one in three women and 15% to 20% of men older than age 65 years have some degree of urinary incontinence. Between 5% and 10% of community-dwelling older adults have incontinence more often than weekly and/or use a pad for protection from urinary accidents. The prevalence is as high as 60% to 80% in many nursing homes, where residents often have both urinary and stool incontinence. In both community and institutional settings, incontinence is associated with both impaired mobility and poor cognition.

Physical health, psychological well-being, social status, and the costs of health care can all be adversely affected by incontinence (Table 8–1). Urinary incontinence is curable or controllable in many geriatric patients, especially those who have adequate mobility and mental functioning. Even when it is not curable, incontinence can always be managed in a manner that keeps people comfortable, makes life easier for caregivers, and minimizes the costs of caring for the condition and its complications.

Physical health Skin irritation and breakdown Recurrent urinary tract infections Falls (especially with nighttime incontinence) Psychological health Isolation Depression Dependency Social consequences Stress on family, friends, and caregivers Predisposition to institutionalization Economic costs Supplies (padding, catheters, etc.) Laundry Labor (nurses, housekeepers) Management of complications |

Despite some change in the social perception of incontinence because of television advertisements and public media and educational efforts, many older people are embarrassed and frustrated by their incontinence and either deny it or do not discuss it with a health professional. It is therefore essential that specific questions about incontinence be included in periodic assessments and that incontinence be noted as a problem when it is detected in institutional settings. Examples of such questions include the following:

- “Do you have trouble with your bladder?”

- “Do you ever lose urine when you don’t want to?”

- “Do you ever wear padding to protect yourself in case you lose urine?”

This chapter briefly reviews the pathophysiology of geriatric incontinence and provides detailed information on the evaluation and management of this condition. Although most of the chapter focuses on urinary incontinence, some of the pathophysiology also applies to fecal incontinence, which is briefly addressed at the end of the chapter.

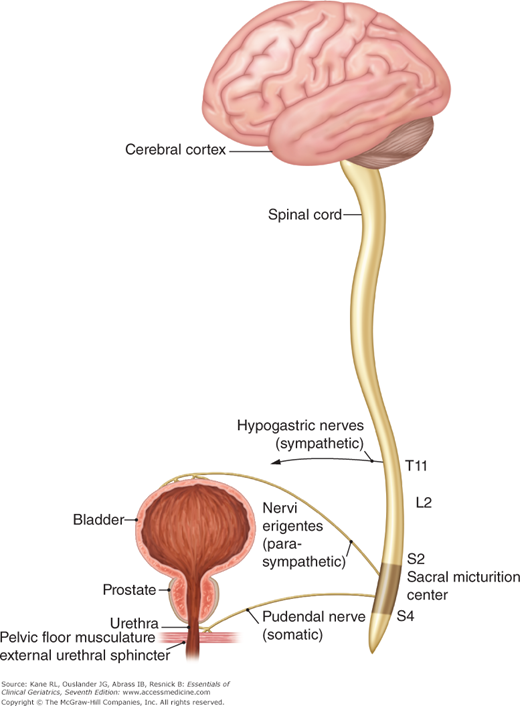

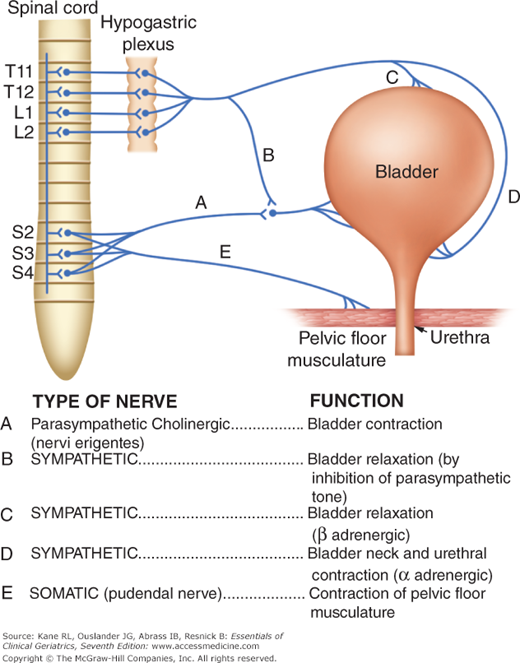

Normal Urination

Continence requires effective functioning of the lower urinary tract, adequate cognitive and physical functioning, motivation, and an appropriate environment (Table 8–2). Thus, the pathophysiology of geriatric incontinence can relate to the anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract as well as to functional, psychological, and environmental factors. Several anatomic components participate in normal urination (Fig. 8-2). Urination is influenced by reflexes centered in the sacral micturition center. Afferent pathways (via somatic and autonomic nerves) carry information on bladder volume to the spinal cord as the bladder fills. Motor output is adjusted accordingly (Fig. 8-3). Thus, as the bladder fills, sympathetic tone closes the bladder neck, relaxes the dome of the bladder, and inhibits parasympathetic tone; somatic innervation maintains tone in the pelvic floor musculature (including striated muscle around the urethra). When urination occurs, sympathetic and somatic tones diminish, and parasympathetic cholinergically mediated impulses cause the bladder to contract. All these processes are under the influence of higher centers in the brain stem, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum.

Effective lower urinary tract function Storage Accommodation by bladder of increasing volumes of urine under low pressure Closed bladder outlet Appropriate sensation of bladder fullness Absence of involuntary bladder contractions Emptying Bladder capable of contraction Lack of anatomic obstruction to urine flow Coordinated lowering of outlet resistance with bladder contractions Adequate mobility and dexterity to use toilet or toilet substitute and to manage clothing Adequate cognitive function to recognize toileting needs and to find a toilet or toilet substitute Motivation to be continent Absence of environmental and iatrogenic barriers such as inaccessible toilets or toilet substitutes, unavailable caregivers, or drug side effects |

This is a simplified description of a very complex process, and the neurophysiology of urination remains incompletely understood. The cerebral cortex exerts a predominantly inhibitory influence, and the brain stem facilitates urination. Thus, loss of the central cortical inhibiting influences over the sacral micturition center from diseases such as dementia, stroke, and parkinsonism can cause incontinence. Disorders of the brain stem and suprasacral spinal cord can interfere with the coordination of bladder contractions and lowering of urethral resistance, and interruptions of the sacral innervation can cause impaired bladder contraction and problems with continence.

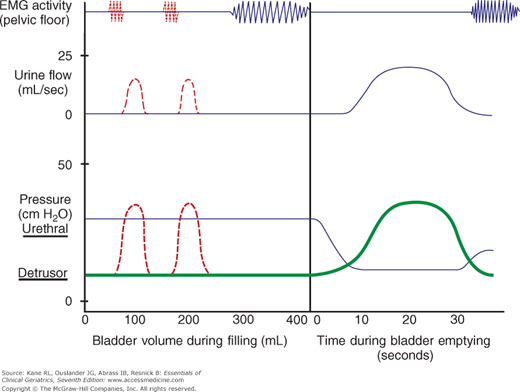

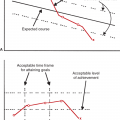

Normal urination is a dynamic process, requiring the coordination of several physiological processes. Figure 8-4 depicts a simplified schematic diagram of the pressure–volume relationships in the lower urinary tract, similar to measurements made in urodynamic studies. Under normal circumstances, as the bladder fills, bladder pressure remains low (eg, <15 cm H2O). The first urge to void is variable but generally occurs between 150 and 300 mL, and normal bladder capacity is 300 to 600 mL. When normal urination is initiated, true detrusor pressure (bladder pressure minus intra-abdominal pressure) increases, urethral resistance decreases, and urine flow occurs when detrusor pressure exceeds urethral resistance. If at any time during bladder filling total intravesicular pressure (which includes intra-abdominal pressure) exceeds outlet resistance, urinary leakage will occur. This will happen if, for example, intra-abdominal pressure rises without a rise in true detrusor pressure when someone with low outlet or urethral sphincter weakness coughs or sneezes. This would be defined as genuine stress incontinence in urodynamic terminology. Alternatively, the bladder can contract involuntarily and cause urinary leakage.

Figure 8-4

Simplified schematic of the dynamic function of the lower urinary tract during bladder filling (left) and emptying (right). As the bladder fills, true detrusor pressure (thick line at bottom) remains low (<15 cm H2O) and does not exceed urethral resistance pressure (thin line at bottom). As the bladder fills to capacity (generally 300-600 mL), pelvic floor and sphincter activity increase as measured by electromyography (EMG). Involuntary detrusor contractions (illustrated by dashed lines) occur commonly among incontinent geriatric patients (see text). They may be accompanied by increased EMG activity in attempts to prevent leakage (dashed lines at top). If detrusor pressure exceeds urethral pressure during an involuntary contraction, as shown, urine will flow. During bladder emptying, detrusor pressure rises, urethral pressure falls, and EMG activity ceases in order for normal urine flow to occur (right side of figure).

Causes and Types of Incontinence

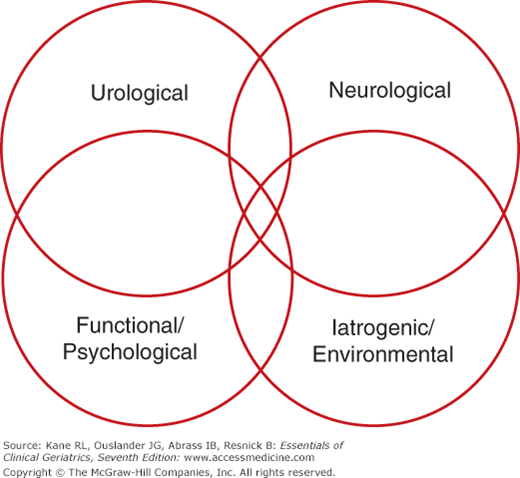

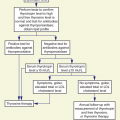

There are four basic categories of causes for geriatric urinary incontinence (Fig. 8-5). Determining the cause(s) is essential to proper management. It is important to distinguish between urological and neurological disorders that cause incontinence and other problems (such as diminished mobility and/or mental function, inaccessible toilets, and psychological problems) that can cause or contribute to the condition. As is the case for a number of other common geriatric problems discussed in this text, multiple disorders often interact to cause urinary incontinence, as depicted in Figure 8-5.

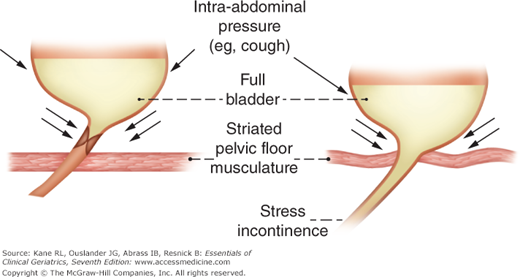

Aging alone does not cause urinary incontinence. Several age-related changes can, however, contribute to its development. In general, with age, bladder capacity declines, residual urine increases, and involuntary bladder contractions become more common. Aging is also associated with a decline in bladder outlet and urethral resistance pressure in women. This decline is related to diminished estrogen influence and laxity of pelvic floor structures associated with prior childbirths, surgeries, and deconditioned muscles, which predisposes to the development of stress incontinence (Fig. 8-6). Decreased estrogen can also cause atrophic vaginitis and urethritis, which can, in turn, cause symptoms of dysuria and urgency and predispose to the development of urinary infection and urgency incontinence. In men, prostatic enlargement is associated with decreased urine flow rates and involuntary bladder contractions and can lead to urgency and/or overflow types of incontinence (discussed later). Aging is also associated with abnormalities of arginine vasopressin (AVP) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) levels. Lack of the normal diurnal rhythm of AVP secretion and increased levels of ANP may contribute to nocturnal polyuria and predispose many older people to nighttime incontinence.

Figure 8-6

Simplified schematic depicting age-associated changes in pelvic floor muscle, bladder, and urethra–vesicle position, predisposing to stress incontinence. Normally (left), the bladder and outlet remain anatomically inside the intra-abdominal cavity, and rises in pressure contribute to bladder outlet closure. Age-associated changes (eg, estrogen deficiency, surgeries, childbirth) can weaken the structures maintaining bladder position (right); in this situation, increases in intra-abdominal pressure can cause urine loss (stress incontinence).

Numerous potentially reversible conditions and medications may cause or contribute to geriatric incontinence (Tables 8-3 and 8-4). The term acute incontinence refers to those situations when the incontinence is of sudden onset, usually related to an acute illness or an iatrogenic problem, and subsides once the illness or medication problem has been resolved (this has also been termed transient incontinence). Persistent incontinence refers to incontinence that is unrelated to an acute illness and persists over time.

Condition | Management |

|---|---|

Conditions affecting the lower urinary tract | |

Urinary tract infection (symptomatic with frequency, urgency, dysuria, etc.) | Antimicrobial therapy |

Atrophic vaginitis/urethritis | Topical estrogen |

Stool impaction | Disimpaction; appropriate use of stool softeners, bulk-forming agents, and laxatives if necessary; implement high fiber intake, adequate mobility, and fluid intake (see Table 8–21) |

Drug side effect (see Table 8–4) | Discontinue or change therapy if clinically appropriate. Dosage reduction or modification (eg, flexible scheduling of rapid-acting diuretics) may also help |

Increased urine production | |

Metabolic (hyperglycemia, hypercalcemia) | Better control of diabetes mellitus Therapy for hypercalcemia depends on underlying cause |

Excess fluid intake | Reduction in intake of diuretic fluids (eg, caffeinated beverages) |

Volume overload | Support stockings |

Venous insufficiency with edema | Leg elevation Sodium restriction Diuretic therapy |

Congestive heart failure | Medical therapy |

Impaired ability or willingness to reach a toilet | |

Delirium | Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause(s) |

Chronic illness, injury, or restraint that interferes with mobility | Regular toileting Use of toilet substitutes Environmental alterations (eg, bedside commode, urinal) Remove restraints if possible |

Psychological | Appropriate nonpharmacologic and/or pharmacologic treatment |

Type of medication | Potential effects on incontinence |

|---|---|

Diuretics | Polyuria, frequency, urgency |

Anticholinergics | Urinary retention, overflow incontinence, stool impaction |

Psychotropics | |

Tricyclic antidepressants | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

Antipsychotics | Anticholinergic actions, sedation, immobility |

Sedative-hypnotics | Sedation, delirium, immobility, muscle relaxation |

Narcotic analgesics | Urinary retention, fecal impaction, sedation, delirium |

α-Adrenergic blockers | Urethral relaxation |

α-Adrenergic agonists | Urinary retention |

Cholinesterase inhibitors | Urinary frequency, urgency |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Cough precipitating stress incontinence |

β-Adrenergic agonists | Urinary retention |

Calcium channel blockers | Urinary retention, edema (nocturia) |

Gabapentin, pregabalin, glitazones | Edema (nocturia) |

Alcohol | Polyuria, frequency, urgency, sedation, delirium, immobility |

Caffeine | Polyuria, bladder irritation |

Potentially reversible conditions can play a role in both acute and persistent incontinence. A search for these factors should be undertaken in all incontinent geriatric patients. The causes of acute and reversible forms of urinary incontinence can be remembered by the mnemonic DRIP (Table 8–5).

Many older persons, because of urinary frequency and urgency, especially when they are limited in mobility, carefully arrange their schedules (and may even limit social activities) in order to be close to a toilet. Thus, any acute illness can precipitate incontinence by disrupting this delicate balance. Hospitalization with its attendant environmental barriers (eg, bed rails, poorly lit rooms) and the immobility that often accompanies acute illnesses can precipitate acute incontinence. Incontinence in these situations is likely to resolve with resolution of the underlying acute illness and hospitalization. Hospital-acquired urinary incontinence can often be prevented. Unless an indwelling or external catheter is necessary during an acute illness to record urine output accurately, this type of incontinence should be managed by environmental manipulation, scheduled toileting, appropriate use of toilet substitutes (eg, urinals, bedside commodes, pads), and careful attention to skin care. Fecal impaction is a common problem in both acutely and chronically ill geriatric patients. Large impactions may cause mechanical obstruction of the bladder outlet in women and may stimulate involuntary bladder contractions induced by sensory input related to rectal distention. Relief of fecal impaction can improve and sometimes resolve the urinary incontinence.

Urinary retention with overflow incontinence should be considered in any patient who suddenly develops urinary incontinence. Immobility, anticholinergic and narcotic drugs, and fecal impaction can all precipitate urinary retention and overflow incontinence in geriatric patients. In addition, this condition may be a manifestation of an underlying acute process causing spinal cord compression.

Any acute inflammatory condition in the lower urinary tract that causes frequency and urgency can precipitate incontinence. Treatment of acute cystitis, atrophic vaginitis, or urethritis can restore continence.

Conditions that cause polyuria, including hyperglycemia and hypercalcemia, as well as diuretics (especially the rapid-acting loop diuretics), can precipitate acute incontinence. Some older people drink excessive amounts of fluids, and others ingest a large amount of caffeine without understanding the effects it can have on the bladder. Patients with volume-expanded states, such as congestive heart failure and lower extremity venous insufficiency, may have polyuria at night, which can contribute to nocturia and nocturnal incontinence.

As in the case of many other conditions discussed throughout this text, a wide variety of medications can play a role in the development of incontinence in elderly patients via several different mechanisms (see Table 8–4). Whether the incontinence is acute or persistent, the potential role of these medications in causing or contributing to patients’ incontinence should be considered. When feasible, stopping the medication, switching to an alternative, or modifying the dosage schedule can be helpful in restoring continence.

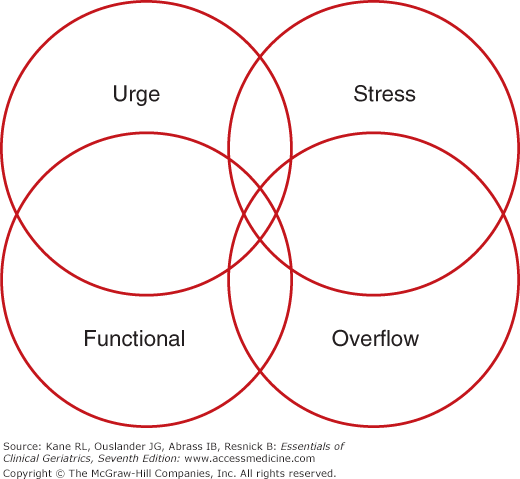

Persistent forms of incontinence can be classified clinically into four basic types. As depicted in Figure 8-7, an individual patient may have more than one type simultaneously. Although this classification does not include all the neurophysiological abnormalities associated with incontinence, it is helpful in approaching the clinical assessment and treatment of incontinence in the geriatric population.

Incontinence can result from one or a combination of the two basic abnormalities in lower genitourinary tract function: (1) failure to store urine, caused by an overactive or poorly compliant bladder or by diminished outflow resistance; and/or (2) failure to empty the bladder, caused by a poorly contractile bladder or by increased outflow resistance. Table 8–6 shows the clinical definitions and common causes of persistent urinary incontinence.

Types | Definition | Common causes |

|---|---|---|

Stress | Involuntary loss of urine (usually small amounts) with increases in intra-abdominal pressure (eg, cough, laugh, exercise) | Weakness of pelvic floor musculature and urethral hypermobility Bladder outlet or urethral sphincter weakness |

Urge | Leakage of urine (variable but often larger volumes) because of inability to delay voiding after sensation of bladder fullness is perceived | Detrusor overactivity, isolated or associated with one or more of the following: Local genitourinary condition such as tumors, stones, diverticula, or outflow obstruction Central nervous system disorders such as stroke, dementia, parkinsonism, spinal cord injury |

Overflow (incontinence associated with incomplete bladder emptying) | Symptoms are variable and nonspecific Classic “overflow” incontinence involves leakage of urine (usually small amounts) resulting from mechanical forces on an overdistended bladder | Anatomic obstruction by prostate, stricture, cystocele A contractile bladder associated with diabetes mellitus or spinal cord injury Neurogenic (detrusor-sphincter dyssynergy), associated with multiple sclerosis and other suprasacral spinal cord lesions |

Functional | Urinary incontinence associated with inability to toilet because of impairment of cognitive and/or physical functioning, psychological unwillingness, or environmental barriers | Severe dementia and other neurological disorders Psychological factors such as depression and hostility |

Stress incontinence is common in older women, especially in ambulatory settings. It may be infrequent and involve very small amounts of urine and need no specific treatment in women who are not bothered by it. On the other hand, it may be so severe and bothersome that it necessitates surgical correction. It is most often associated with weakened supporting tissues (of the pelvic floor) and consequent hypermobility of the bladder outlet and urethra caused by lack of estrogen and/or previous vaginal deliveries or surgery (see Fig. 8-6). Obesity and chronic coughing can exacerbate this condition. Women who have had previous vaginal repair and/or surgical bladder neck suspension may develop a weak urethra (intrinsic sphincter deficiency [ISD]). These women generally present with severe incontinence and symptoms of urinary loss with any activity. This condition should be suspected during office evaluation if a woman loses urine involuntarily with coughing in the supine position during a pelvic examination when her bladder is relatively empty. In general, women with ISD are less responsive to nonsurgical treatment but may benefit from periurethral injections or a surgical sling procedure. Stress incontinence is unusual in men but can occur after transurethral surgery and/or radiation therapy for lower urinary tract malignancy when the anatomic sphincters are damaged.

Urgency incontinence can be caused by a variety of lower genitourinary and neurological disorders (see Table 8–6). Patients with urgency incontinence typically present with irritating symptoms of an overactive bladder, including frequency (voiding more than every 2 hours), urgency, and nocturia (two or more voids during usual sleeping hours). Urgency incontinence is most often, but not always, associated with involuntary bladder contractions on urodynamic testing (see Fig. 8-4). Some patients have a poorly compliant bladder without involuntary contractions (eg, as a result of radiation or interstitial cystitis, both relatively unusual conditions).

Other patients have symptoms of urgency incontinence but do not exhibit involuntary bladder contractions on urodynamic testing. Some patients with neurological disorders have involuntary bladder contractions on urodynamic testing but do not have urgency and are incontinent without any warning symptoms. These patients are generally treated as if they had urgency incontinence if they empty their bladders and do not have other correctable genitourinary pathology. A subgroup of older incontinent patients with an overactive bladder also have impaired bladder contractility—emptying less than one-third of their bladder volume with involuntary contractions on urodynamic testing (Resnick and Yalla, 1987; Elbadawi, Yalla, and Resnick, 1993). This condition has been termed detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility (DHIC). Patients with DHIC may present with symptoms that are not typical of urge incontinence and may strain to complete voiding. These patients may be challenging to manage because of their incomplete bladder emptying (Taylor and Kuchel, 2006).

Some older patients suffer from an overactive bladder but are not incontinent. The hallmark symptom of overactive bladder is urinary urgency. Patients with overactive bladder usually also complain of urinary frequency (more than eight voids in 24 hours) and nocturia (awakening from sleep to void). Overactive bladder symptoms are common in the elderly; approximately 30% of women and 40% of men age 75 and older admit to these symptoms, most of whom also have urgency incontinence. The conditions that contribute to symptoms of overactive bladder as well as the diagnostic evaluation and management of this symptom complex are the same as for urgency incontinence (Ouslander, 2004).

Incontinence associated with incomplete bladder emptying can result from anatomic or neurogenic outflow obstruction, a hypotonic or acontractile bladder, or both. The most common causes include prostatic enlargement, diabetic neuropathic bladder, and urethral stricture. Low spinal cord injury and anatomic obstruction in females (caused by pelvic prolapse and urethral distortion) are less common causes of overflow incontinence. Several types of drugs can also contribute to this type of persistent incontinence (see Table 8–4). Some patients with suprasacral spinal cord lesions (eg, multiple sclerosis) develop detrusor-sphincter dyssynergy and consequent urinary retention, which must be treated in a similar manner as overflow incontinence; in some instances, a sphincterotomy is necessary. The symptoms of this type of incontinence are nonspecific, and urinary retention is easily missed on physical examination. Thus, a postvoid residual determination must be performed to exclude this condition.

The term functional incontinence refers to incontinence associated with the inability or lack of motivation to reach a toilet on time. Factors that contribute to functional incontinence (such as inaccessible toilets and psychological disorders, especially dementia) can also exacerbate other types of persistent incontinence. Patients with incontinence that appears to be predominantly related to functional factors may also have abnormalities of the lower genitourinary tract. In some patients, it can be very difficult to determine whether the functional factors or the genitourinary factors predominate without a trial of specific types of treatment. However, no matter what specific treatments are prescribed, patients with functional incontinence require systematic toileting assistance as a component of their management plan.

These basic types of incontinence may occur in combination in an individual patient, as depicted by the overlap in Figure 8-7. Older women commonly have a combination of stress and urgency incontinence (generally referred to as mixed incontinence). Frail geriatric patients often have urgency incontinence as well as functional disabilities that contribute to their incontinence.

Evaluation

The first step in evaluating incontinent patients is to identify the incontinence by direct observation or using the screening questions discussed earlier. In patients with the sudden onset of incontinence (especially when associated with an acute medical condition and hospitalization), the common reversible factors that can cause acute incontinence (see Tables 8-3, 8-4 and 8-5) can be ruled out by a brief history, physical examination, postvoid residual determination, and basic laboratory studies (urinalysis, culture, and serum glucose).

Table 8–7 shows the components of the basic evaluation of persistent urinary incontinence. Practice guidelines suggest that the basic evaluation should include a focused history, targeted physical examination, urinalysis, and postvoiding residual (PVR) determination in most patients (Fantl et al., 1996; American Medical Directors Association, 2006; Fung et al., 2007). The history should focus on the characteristics of the incontinence, current medical problems and medications, the most bothersome symptom(s), and the impact of the incontinence on the patient and caregivers (Table 8–8). Bladder records or voiding diaries such as those shown in Figure 8-8 (for outpatients) and Figure 8-9 (for institutionalized patients) can be helpful in initially characterizing symptoms as well as in following the response to treatment.

All patients History, including bladder record Physical examination Urinalysis Postvoid residual determination* Selected patients† Laboratory studies Urine culture Urine cytology Blood glucose, calcium Renal function tests Renal ultrasonography Gynecological evaluation Urological evaluation Cystourethroscopy Urodynamic tests Simple Observation of voiding Cough test for stress incontinence Complex Urine flowmetry‡ Multichannel cystometrogram Pressure-flow study Leak-point pressure Urethral pressure profilometry Sphincter electromyography Video urodynamics |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree