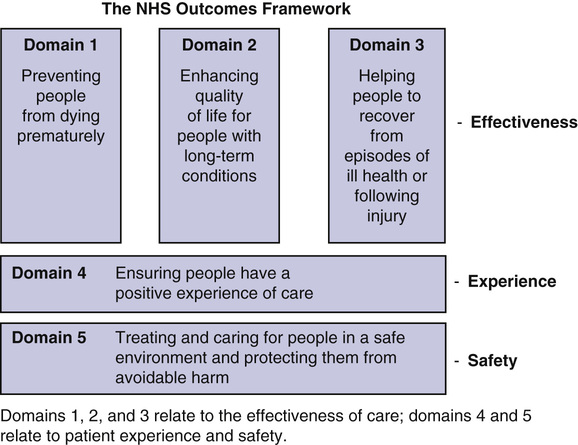

Jim George, Henry J. Woodford, James M. Fisher A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members. Mahatma Gandhi Measuring and monitoring quality of care in the National Health Service (NHS) in England has attracted sustained attention over the past several years. The 2008 Darzi report (“High Quality Care for All”) was designed to place the focus of the NHS firmly on quality.1 However, few could have anticipated the two Francis inquiries2,3 in 2010 and 2013, the Keogh mortality review4 and the Berwick report,5 all of which profoundly influenced the Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspection regimes that are designed to improve the quality of care in the NHS, particularly for older people. The most vulnerable patients are older adults: people older than 85 years account for only 8.3% of admissions to hospital but 21% of patient safety incidents.6 Standards for care for older people act as an overall barometer for quality of care in the NHS. The aim of this chapter is to take readers through the experience of the NHS in England over the past several years so that they can learn from the mistakes and successes and, hopefully, be in a better position to continue their own quality improvement journey. There is no universally accepted definition of quality. A broad understanding is “doing the right things well.” Donabedian made the classic distinction between the structure, processes, and outcomes of health care and argued that processes and outcomes should be assessed seperately.7 Donabedian also emphasized that quality of health care not only includes technical excellence but also the manner and humanity in which it is delivered—hence the importance of processes or systems. Maxwell took this further by defining six dimensions of quality: (1) access, (2) relevance to need, (3) effectiveness, (4) equity, (5) social acceptability, and (6) efficiency and economy.8 It is interesting that safety does not feature in Maxwell’s list of quality dimensions. It was not until 1999 with the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s report “To Err Is Human”9 that it was generally realized that health care can sometimes be harmful, and safety was put at the forefront of quality. This is particularly relevant to older people among whom adverse events, such as falls, delirium, pressure ulcers, deconditioning, and medication errors, are so common.6 The more recent Institute of Medicine definition of quality includes six domains10: safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. For older people in the NHS, a seventh domain needs to be added: continuity and coordination of care.11 The Darzi Next Stage Review was commissioned by the government to set a vision for the NHS in the twenty-first century. (Professor Darzi is an eminent colorectal surgeon and a former health minister.) The report “High Quality Care for All” was issued in June 2008. The key theme was there should be no new central targets; instead, clinicians would be expected to lead, and not just manage, a service and create a shared vision to drive improvements in safety and quality.1 This led to the NHS Outcomes Framework, which targeted three distinct areas of quality (Figure 127-1): 2. The safety of the treatment and care provided to patients 3. The broader experience patients have of the treatment and care they receive The NHS Outcomes Framework is supported by the development of quality standards by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE); the introduction of best practice tariffs (e.g., for stroke and neck of femur fracture) to encourage hospital trusts to provide the best possible care by paying them more if it is achieved; and the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) framework in which trusts are penalized for not achieving best quality standards (e.g., for dementia care and prevention of thromboembolism). In 2009 the Health Care Commission (the NHS regulator prior to the CQC) published the findings of an investigation into the reported widespread care failures at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. The focus was on poor quality of care of older patients in Stafford Hospital, a district general hospital in England. It is troublesome that the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust had achieved coveted “foundation status” while the problems were ongoing. A local campaign group, Cure the NHS, lobbied for an inquiry. The first Francis inquiry was designed to identify the key failures in Mid Staffordshire and make recommendations. It was led by Robert Francis, QC, an eminent lawyer. Key failures identified were the following: 6. Poor diagnosis and management, especially in acute emergency patients. 7. A bullying culture, target focused and needs of patients ignored. Quote from Francis inquiry (2010): It appears from the evidence presented at oral hearings that many patients suffered from acute confusional states: this occurs in a high proportion of older people admitted to hospital with serious illness. The evidence suggests that some medical staff did not understand this diagnosis and its importance, and in some instances treated it as “bad behaviour,” rather than a valid medical condition. The second Francis inquiry looked at wider NHS issues and focused on why the serious failings in Mid Staffordshire were not recognized earlier by inspection, commissioning, supervision, and regulation of the hospital. The inquiry highlighted the following further issues relevant to the quality of care of older people: 2. Doctors (particularly consultants) failed to speak up for patients 3. Defensiveness, secrecy, and complacency; ignoring basic standards of care 4. Poor monitoring arrangements 5. Poor accountability with “diffusion” of responsibility 6. Lack of nurse training (particularly in older adult care) and lack of compassion 7. “Blind trust” in the hospital management and lack of external checks The second Francis inquiry made more than 200 recommendations, including the following: 1. Patient safety should be the number one priority. 2. Quality accounts should be published in a common format and made public. 3. The profession of health care assistants should be regulated. 4. For older adults, one person should be made responsible for individual care and maintain continuity. 5. Patient involvement should be increased. 6. Staff and hospitals should speak up and be honest about mistakes. The recommendations of the second Francis inquiry have been accepted by the government.12 Both inquiries recognized the crucial importance of improving quality of care for older people and that this requires specialist skills and training. Subsequently, the government made the care of older people and, in particular, people with dementia central to NHS policy. Although the findings of the Francis inquiries were very distressing to many who work in the care of older people, the specialty of geriatric medicine has become more prominent in the NHS. Older patients and their caregivers and relatives are now much more encouraged to comment on the services provided, and the leadership and management skills of geriatricians are consequently more appreciated. Following the publication in February 2013 of the second Francis inquiry, Sir Bruce Keogh (National Medical Director) led a review of 14 trusts in July 2013, purposely selected because they had higher than average mortality rates. The Keogh report4 found key issues in the 14 trusts, all relating to quality. The review team talked directly to patients and also received written feedback. There was a tendency in many of the hospitals to view complaints as something to be managed rather than to inform and be acted upon. Safety is a key indicator of overall quality of care. National indicators measuring safety and harm are included in the NHS Safety Thermometer (see later). In particular, infection rates and pressure ulcer rates were measured, as well as mortality rates. The review teams found there was scope for improvement in the use of early warning scores to anticipate and prevent acute deterioration of patients. It also found there was room for improvement in organizational learning from safety incidents. In some of the hospitals, multiple serious events had occurred with the same theme, indicating that lessons had not been learned. Many of the hospitals had medical and nurse staffing problems with difficulties in recruitment, high sickness rates, and frequent use of locums and agency staff. There was a statistical relationship between inpatient staff ratios and standardized mortality rates. All of the hospitals reviewed were functioning at high levels of capacity. Much of the pressure was due to large increases in the number of older patients with complex health problems. The Keogh review teams found evidence of the following: The Keogh report of 14 trusts confirmed that many of the quality deficiencies found in the Francis reports were not unique. A common factor in all 15 trusts (Keogh 14, plus Mid-Staffordshire) were workforce, training, safety, quality, and governance issues, exacerbated by the pressures caused by an increase in older adult acute emergency admissions. The findings of the Keogh Review led to immediate changes in the CQC hospital investigation process.13 The Francis report1 highlights the unique perspective junior doctors possess with regard to patient safety, describing them as “the eyes and ears” of the United Kingdom’s NHS. The junior doctors’ comparative lack of experience relative to more senior colleagues can be seen as beneficial, because they are less likely to be “infected” by any unhealthy local cultures. Furthermore, junior doctors in training regularly move between clinical sites. This provides a unique perspective on potential variance of quality between institutions. Consequently, it has been suggested that junior doctors are perhaps more likely to perceive practice to be unacceptable than staff who have worked in the same clinical environment for a much longer period. The Francis report also highlighted that, in a number of instances, concerns regarding suboptimal care had been raised by junior doctors but not acted upon. The report recommends that such concerns should be rigorously explored and not discounted simply on the basis of a lack of experience or seniority. The importance of providing appropriate forums for junior doctors to voice concerns is also highlighted. Suggested methods include trainee surveys and face-to-face feedback during visits that relate to approval or accreditation of training placements. The Keogh report4 directly acknowledges the contribution junior doctors can make to patient safety, describing them as “potentially our most powerful agents for change.” Junior doctors were included in each of the rapid responsive review teams that were assembled to collect data in trusts. Junior doctor involvement is now integrated into the team employed by the CQC to undertake a hospital trust inspection. The Keogh report calls upon medical directors to consider how the latent energy of junior doctors can be “tapped” rather than “sapped” and also issues a call to arms to junior doctors themselves, citing them as “not just the clinical leaders of tomorrow, but clinical leaders of today.” With this in mind, trusts should be encouraging junior doctors to act as conduits through which good practice can be shared between institutions. The National Advisory Group on Safety in Patients in England led by Professor Don Berwick gathered information from the Francis and Keogh reports and combined it with additional statements from patients and experts. The Berwick report concentrated on the cultural changes required. Recommendations included the following: 1. Abandon blame as a tool for change and trust the goodwill and good intentions of the staff. 2. Emphasize patient-centered care. 3. Recognize that transparency is essential. 4. Give the NHS career staff training in quality improvement methods. 5. Culture change is more important than rules and regulations for a safer NHS. The CQC is an independent care regulatory body and describes its functions as ensuring that the care provided by hospitals, dentists, ambulances, care homes, and home-care agencies meet government standards of quality and safety.14 Recent radical changes have been made to the CQC inspection methodology.15 Moving away from inspecting individual aspects of care, the CQC now aspires to inspect a health care provider as a whole. Rather than just trying to establish and identify problems, the CQC wants to be able to get under the skin of the organization to understand the cause of problems. To use the analogy of an unwell patient, it aims not only to determine symptoms and signs but also reach a diagnosis.15 In acute trusts, eight core services will always be inspected: accident and emergency, medicine (including older adult care), critical care, maternity, pediatrics, end-of-life care, and outpatients. The assessment is divided into three parts: preinspection, inspection, and postinspection. In the preinspection phase, data are collected from national data sources, the trust, and stakeholders. During the inspection, the CQC seeks to assess five questions, each related to a quality domain: 1. Is it safe (are people protected from harm)? 2. Is it effective (do patients have good outcomes)? 3. Is it caring (do staff look after people well)? 4. Is it responsive (does the trust organize its services in a patient-centered manner)? A large team, comprising clinical experts, lay people, junior doctors, and nurses, are brought together to undertake an inspection over a 2- to 4-day period (Box 127-1). Trusts are rated on a 4-point scale identical to that used by Ofsted (the education regulator); the ratings are outstanding, good, requires improvement, or inadequate. Informal feedback suggests that this new approach to inspection by the CQC represents a significant improvement.15 The hope is that it will eventually result in improvements to the quality of care for older people. The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) report “Hospitals on the Edge”16 highlighted services having to cope with increasing numbers of older patients with complex needs and difficulties in providing continuing care to these patients and the challenges maintaining medical services after hours and on weekends. The RCP convened an independent group, The Future Hospital Commission, to discuss potential remedies to this crisis in care.17 The solution proposed was that care oriented around the patient’s needs should be achieved by increasing the proportion of generalists (e.g., geriatricians). The report went further by suggesting more integration of health and social care teams and that acute care should be coordinated better beyond the hospital walls. The care priorities identified by the Future Hospital Commission are summarized in Box 127-2.

Improving Quality of Care for Older People in England

What Is Quality?

NHS Strategy to Improve Quality

The Francis Inquiries (2010 and 2013)

The First Francis Inquiry (2010)2

The Second Francis Inquiry (2013)3

The Keogh Report4

Patient Experience

Patient Safety

Workforce

Leadership and Governance

Junior Doctors’ Response and Involvement in the Francis and Keogh Reports

Berwick Report (2013)5

Care Quality Commission

The Future Hospital Commission

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Improving Quality of Care for Older People in England

127