Immunotherapy for Inhalant Allergens

Harold S. Nelson

I. INTRODUCTION

Immunotherapy was first introduced as a treatment for grass pollen-induced “hay fever” in 1911. Beginning out of season, Noon and Freeman injected patients subcutaneously with increasing doses of grass pollen extract. Their reported success led to rapid adoption of this treatment not only for other pollen but also for a range of perennial allergens, such as house dust and animal danders, as well as for fungi. It was half a century following its introduction before adequately controlled studies proved the effectiveness of immunotherapy for hay fever and asthma and for mixes of multiple allergens. Other studies confirmed that the response was limited to the allergen that was being injected. More recent studies have documented the disease-modifying potential of immunotherapy. Controlled studies have proven that the benefits derived from immunotherapy persist for years following discontinuation of an adequate course of treatment. Further, in patients with a single sensitivity, immunotherapy greatly decreases the likelihood of developing addition sensitivities, and in those with only allergic rhinitis it decreases the likelihood of developing asthma. Immunotherapy is widely employed for treating patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma, but there are many patients who would likely benefit but are not receiving it. There are multiple reasons for this underutilization of immunotherapy, but two main ones are the occurrence of adverse reactions that can be severe and the inconvenience of repeated visits to a physician’s office over a period of several years. Both of these concerns are being addressed by the development of alternative methods of immunotherapy, both administering currently available allergen extracts by routes other than injection and by modifying the allergen extracts to make them less reactive with immunoglobulin E (IgE) and yet retaining their immunogenicity for the T cells, which is thought to be the important mechanism of improvement.

II. CLINICAL INDICATIONS FOR IMMUNOTHERAPY

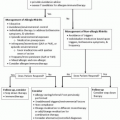

Immunotherapy was initially introduced for treatment of allergic rhinitis due to grass, and the definitive proof of efficacy was obtained with ragweed pollen extract in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Subsequently, placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated efficacy with several other pollen and also with house dust mite extract in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis. Immunotherapy was used in patients with bronchial asthma soon after its introduction, but the clinical results were not as consistent as those with allergic rhinitis. However, any question regarding efficacy of immunotherapy for asthma has been dispelled by a series of meta-analyses that include all randomized, controlled trials. The most recent, a Cochrane systematic analysis included 88 clinical trials and

concluded that there was a significant improvement in asthma symptom scores (standardized mean difference—0.59). Attempts to treat patients with allergy to peanuts with injection immunotherapy were not successful due to repeated systemic reactions, and it is generally accepted that injection therapy is not indicated for food allergy. Currently, oral and sublingual approaches to immunotherapy for food allergy are being investigated (see chapter 16 on Allergic and Nonallergic Reactions to Food). Until recently, atopic dermatitis was not considered an indication for immunotherapy; however, two recent studies with house dust mite extract, one by injection and one by the sublingual route, reported favorable results. If these are confirmed, immunotherapy may be considered appropriate for selected patients with atopic dermatitis. Immunotherapy is an accepted treatment for sensitivity to venom on the flying Hymenoptera and imported fire ants (covered in Chapter 14 on Insect Allergy).

concluded that there was a significant improvement in asthma symptom scores (standardized mean difference—0.59). Attempts to treat patients with allergy to peanuts with injection immunotherapy were not successful due to repeated systemic reactions, and it is generally accepted that injection therapy is not indicated for food allergy. Currently, oral and sublingual approaches to immunotherapy for food allergy are being investigated (see chapter 16 on Allergic and Nonallergic Reactions to Food). Until recently, atopic dermatitis was not considered an indication for immunotherapy; however, two recent studies with house dust mite extract, one by injection and one by the sublingual route, reported favorable results. If these are confirmed, immunotherapy may be considered appropriate for selected patients with atopic dermatitis. Immunotherapy is an accepted treatment for sensitivity to venom on the flying Hymenoptera and imported fire ants (covered in Chapter 14 on Insect Allergy).

Immunotherapy has been demonstrated to be effective in children; generally the same doses are employed as in adults. Previously, it was widely stated that children <6 years of age should not receive immunotherapy. The principal arguments against administration to younger children were that there might be difficulty diagnosing a systemic reaction in a young child and that the injections would be very traumatic to young children. More recently, several studies have been reported in which children as young as 3 years of age were treated with injection immunotherapy without adverse outcomes. These reports, plus the now recognized effect of immunotherapy in reducing new sensitizations and progression from allergic rhinitis to asthma, have led to a more flexible approach to immunotherapy in young children.

III. DISEASE MODIFICATION BY IMMUNOTHERAPY

In addition to improving the course of the allergic condition while it is continued, immunotherapy has been shown to reduce the likelihood of development of new sensitivities in monosensitized patients, to reduce the likelihood of developing asthma in patients who only have allergic rhinitis, and to produce benefit in the clinical condition persisting for years following its discontinuation. All these effects are evidence of a modification in the underlying disease process. In studies of monosensitized children and young adults, immunotherapy administered for three years reduced, at follow-up three years after discontinuation, new sensitization from two-thirds in the controls to one-quarter in the treated subjects. In children who received birch and/or timothy immunotherapy for 3 years, the likelihood of not developing asthma at the end of immunotherapy was 2.52 compared to controls, and it remained 2.48 seven years after immunotherapy was discontinued. In a study of grass-sensitive patients who had responded well after 3 or 4 years of immunotherapy, symptomatic improvement was shown to persist in 70% 4 years after discontinuation of treatment.

IV. ALLERGENS EMPLOYED FOR IMMUNOTHERAPY

A. Standardized extracts

Currently, in the United States, there are a number of allergen extracts that have been standardized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The methods of standardization vary within this group. All standardized extracts are available only in 50% glycerin solutions.

1. Grass pollen extracts

Grass extracts (timothy, orchard, Kentucky blue, red top, perennial rye, meadow fescue, sweet vernal, and Bermuda) have been standardized initially by quantitative intradermal skin testing in highly allergic subjects. Subsequent lots are compared to an FDA standard using in vitro methods. The grasses are assigned potencies of 10,000 and/or 100,000 bioequivalent allergy units (BAU), the most potent being used for the formulation of extracts for immunotherapy.

2. Short ragweed pollen extract

Short ragweed extracts are sold using standard nomenclature of weight by volume; however, their content of the major allergen of short ragweed, Amb a 1, that must fall within defined limits is listed on the label in FDA units. The 1:10 w/v short ragweed is also considered to contain 100,000 Allergy Units (AU) per milliliter.

3. Cat extract

Cat extracts may be either hair and dander or pelt. In either case, the content of the major allergen, Fel d 1, must be between 10.0 and 19.9 FDA U/mL. The two extracts differ in that pelt has a higher content of cat serum albumin. Cat extracts are expressed in BAU and available as 5,000 and 10,000 BAU/mL.

4. House dust mite extract

The two house dust mite extracts, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and D. farinae, were initially standardized by quantitative intradermal skin testing, and subsequent lots are compared to the FDA standard by in vitro testing. House dust mite potency is expressed as Allergy Units that correspond to BAU and are available in potencies ranging from 3,000 to 30,000 AU/mL.

B. Unstandardized extracts

The potency of unstandardized extracts may be expressed as weight of extracted material divided by volume of extracting fluid (w/v) or by the content of protein in the extract (Protein Nitrogen Units or PNU). Most extracts are available as either aqueous or 50% glycerin solutions. Aqueous solutions are generally recommended for pollen since they are more concentrated and glycerin causes pain on injection in a dose-dependent manner. Cockroach and fungal extracts, on the other hand, contain proteolytic activity that is at least in part inhibited by glycerin. Hence, only glycerinated extracts should be used for these allergens.

Some pollen are also available in the United States in an alum-precipitated formulation. These extracts have been shown to cause fewer systemic reactions than aqueous extracts.

1. Pollen extracts

When the major allergen content of unstandardized pollen extracts has been measured, it has fallen within the range of major allergen content of standardized pollen extracts. Therefore, it is usually recommended that unstandardized pollen extracts be used in approximately the same or up to twice the dose of the standardized pollen extracts.

2. Dog extract

Most commercial dog extracts are of very low potency, making their use for immunotherapy of questionable efficacy. The exception is an acetone-precipitated dog extract from Hollister-Stier Laboratories which

has been shown by in vitro analysis and skin testing to be roughly 35 times more potent than the average commercial dog extract. This extract is available in a 1:100 w/v concentration, with a known major allergen (Can d 1) content of 140 to 160 µg/mL.

has been shown by in vitro analysis and skin testing to be roughly 35 times more potent than the average commercial dog extract. This extract is available in a 1:100 w/v concentration, with a known major allergen (Can d 1) content of 140 to 160 µg/mL.

3. Cockroach extract

Only extracts in 50% glycerin have been shown to have significant allergenic activity. A recent assessment of three commercially available German cockroach extracts revealed potencies of 1,738 to 8,570 BAU/mL suggesting they could be used for immunotherapy, but the doses (in milliliters of concentrate) would have to be considerable greater than those used for pollen.

4. Fungal extracts

The major allergen content of commercially available fungal extracts has been examined for Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus, Penicillium notatus, Epicoccus nigrum, Helminthosporium setivus, and Aureobasidium pullalans. For each of these species, the major allergen content has varied more than 100-fold from one company’s product to another. The dose of these extracts required for effective immunotherapy is, for the most part, unknown, so the dose to be used is also unknown. It has been recommended in the Immunotherapy Practice Parameters to use the highest tolerated dose.

C. Standardization of allergen extracts in Europe

There is no authority in Europe similar to the FDA in the United States. Allergen extract companies tend to establish their own internal standard for potency, often based on reactivity of allergic patients to the allergen extract and to a nonspecific agent such as codeine or histamine. Several studies suggest widely varying potency among European allergen extracts sold for the same indication.

D. Standardization by major allergen content

In view of the differing methods of expressing potency used in the United States and in Europe, the only common terminology available for comparing studies worldwide is to express dosing as the micrograms of major allergen administered as a maintenance injection. Major allergen content is usually measured by the use of monoclonal antibodies. One problem is that multiple monoclonal antibodies are employed, and they may differ from one another in their quantitation of a major allergen. Nevertheless, it is the best measure of dosing and potency available at this time.

V. PREPARATION OF AN ALLERGEN EXTRACT FOR INJECTION IMMUNOTHERAPY

In preparation of an extract for immunotherapy, there are three considerations: (1) administration of a dose for each allergen that has been shown to be clinically effective in double-blind placebo-controlled trials or, when such data is not available, the optimal dose by inference from what is known regarding the potency of the extract; (2) attention to cross-allergenicity among the extracts employed so that an excess of one allergenic specificity will not limit dosing for the remainder; and (3) attention to the presence of proteolytic activity in extracts so that susceptible allergens are not degraded by the proteolytic activity in others.

A. Dosing

Due to the large placebo effect regularly encountered in immunotherapy plus the variations in exposure to allergens from season to season and location to location, effective dosing can only be determined by randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Effective doses expressed by their major allergen content have been established for all of the standardized extracts: short ragweed, timothy grass, birch, house dust mites, cat, dog, and Alternaria (Table 6-1). From this information, it is possible to estimate what the effective dose will be of nonstandardized extracts, providing there is some information regarding their usual content of major allergen and providing there is a reasonable range of variability of potency of the extracts. This latter constraint probably is true for pollen but not for the fungal extracts that have been tested.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree