Immobility: Introduction

Although mobility can be achieved by using various devices, the discussion here emphasizes walking. Immobility refers to the state in which an individual has a limitation in independent, purposeful physical movement of the body or of one or more lower extremities. Immobility can trigger a series of subsequent diseases and problems in older individuals that produce further pain, disability, and impaired quality of life. Optimizing mobility should be the goal of all members of the health-care team working with older adults. Small improvements in mobility can decrease the incidence and severity of complications, improve the patient’s well-being, and decrease the cost and burden of caregiving.

Causes

Immobility can be caused by a wide variety of factors. The causes of immobility can be divided into intrapersonal factors including psychological factors (eg, depression, fear of falling or getting hurt, motivation), physical changes (cardiovascular, neurological, and musculoskeletal disorders, and associated pain), and environmental causes. Examples of these physical, psychological, and environmental factors include inappropriate caregiving, paralysis, lack of access to appropriate assistive devices, and environmental barriers such as lack of handrails on stairs or grab bars around a commode (Table 10–1).

Musculoskeletal disorders Arthritides Osteoporosis Fractures (especially hip and femur) Podiatric problems Other (eg, Paget disease) Neurological disorders Stroke Parkinson disease Neuropathies Normal-pressure hydrocephalus Dementias Other (cerebellar dysfunction, neuropathies) Cardiovascular disease Congestive heart failure (severe) Coronary artery disease (frequent angina) Peripheral vascular disease (frequent claudication) Pulmonary disease Chronic obstructive lung disease (severe) Sensory factors Impairment of vision Decreased kinesthetic sense Decreased peripheral sensation Environmental causes Forced immobility (in hospitals and nursing homes) Inadequate aids for mobility Acute and chronic pain Other Deconditioning (after prolonged bed rest from acute illness) Malnutrition Severe systemic illness (eg, widespread malignancy) Depression Drug side effects (eg, antipsychotic-induced rigidity) Fear of falling Apathy and lack of motivation |

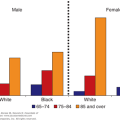

The incidence of degenerative joint disease (DJD) is particularly high in older adults, although symptoms of disease may not manifest in all individuals who have radiographic changes (Lawrence et al., 2008). The pain and musculoskeletal changes associated with DJD can result in contractures and progressive immobility if not appropriately treated. In addition, podiatric problems associated with degenerative changes in the feet (eg, bunions and hammertoes) can likewise cause pain and contractures. These changes can result in painful ambulation and a subsequent decrease in the older individual’s willingness and ability to ambulate. Patients who have had a stroke resulting in partial or complete hemiparesis/paralysis, spinal cord injury resulting in paraplegia or quadriplegia, fracture or musculoskeletal disorder limiting function, or prolonged bed rest after surgery or acute illness are considered immobilized. Approximately 8% of older adults in the 60- to 79-year age group experience a stroke, and this rate doubles in adults age 80 and above (American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association, 2012). About half of the individuals who suffer a stroke have residual deficits for which they require assistance, and often these deficits result in immobility. Parkinson disease (PD), another common neurological disorder found in older adults, can cause severe limitations in mobility. PD is a progressive neurological disorder that affects approximately 1% of the population over the age of 60 (European Parkinson’s Disease Association, 2012). As the disease progresses, it has a major impact on the individual’s function caused by the associated bradykinesia (slow movement) or akinesia (absence of movement), resting tremor, and muscle rigidity, as well as cognitive changes.

Severe congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease with frequent angina, peripheral vascular disease with frequent claudication, orthostatic hypotension, and severe chronic lung disease can restrict activity and mobility in many elderly patients because of lack of cardiovascular endurance. Peripheral vascular disease, especially in older diabetics, can cause claudication, peripheral neuropathy, and altered balance, all of which limit ambulation.

The psychological and environmental factors that influence immobility are as important as the physical changes noted. Depression, lack of motivation, apathy, fear of falling, and health beliefs (ie, a belief that rest and immobility are beneficial to recovery) can all influence mobility in older adults. Both the social and physical environment can have a major impact on mobility. Well-meaning formal and informal caregivers may provide care for older individuals rather than help the individual optimize their underlying function. Inappropriate use of wheelchairs, bathing, and dressing of individuals who have the underlying capability to engage in these activities results in deconditioning and immobility. Lack of mobility aids (eg, canes, walkers, and appropriately placed railings), cluttered environments, uneven surfaces, and the shape of and positioning of chairs and beds can further lead to immobility. Negotiating stairs can be a special challenge.

Drug side effects may also contribute to immobility. Sedatives and hypnotics can result in drowsiness, dizziness, delirium, and ataxia, and can impair mobility. Antipsychotic drugs (especially the typical antipsychotic agents) have prominent extrapyramidal effects and can cause muscle rigidity and diminished mobility. The treatment of hypertension can result in orthostatic hypotension or bradycardia such that the individual experiences dizziness and is unable to ambulate independently.

Complications

Immobility can lead to complications in almost every major organ system (Table 10–2). Prolonged inactivity or bed rest has adverse physical and psychological consequences. Metabolic effects include a negative nitrogen and calcium balance and impaired glucose tolerance. Older individuals can also experience diminished plasma volume and subsequent changes in drug pharmacokinetics. Immobilized older patients often become depressed, are deprived of environmental stimulation, and, in some instances, become delirious. Deconditioning can occur rapidly, especially among older individuals who have little physiological reserve.

Skin Pressure ulcers Musculoskeletal Muscular deconditioning and atrophy Contractures Bone loss (osteoporosis) Cardiovascular Deconditioning Orthostatic hypotension Venous thrombosis, embolism Pulmonary Decreased ventilation Atelectasis Aspiration pneumonia Gastrointestinal Anorexia Constipation Fecal impaction, incontinence Genitourinary Urinary infection Urinary retention Bladder calculi Incontinence Metabolic Altered body composition (eg, decreased plasma volume) Negative nitrogen balance Impaired glucose tolerance Altered drug pharmacokinetics Psychological Sensory deprivation Delirium Depression |

Musculoskeletal complications associated with immobility include loss of muscle strength and endurance; reduced skeletal muscle fiber size, diameter, and capillarity; contractures; disuse osteoporosis; and DJD. The severity of muscle atrophy is related to the duration and magnitude of activity limitation. If left unchecked, this muscle wasting can lead to long-term sequelae, including impaired functional capacity and permanent muscle damage. Moreover, immobility exacerbates bone turnover by resulting in a rapid and sustained increase in bone resorption and a decrease in bone formation. The impact of immobility on skin can also be devastating. Varying degrees of immobility and decreased serum albumin significantly increase the risk for pressure ulcer development. Prolonged immobility results in cardiovascular deconditioning; the combination of deconditioned cardiovascular reflexes and diminished plasma volume can lead to postural hypotension. Postural hypotension may not only impair rehabilitative efforts but also predispose to falls and serious cardiovascular events such as stroke and myocardial infarction. Likewise, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are well-known complications. Immobility, especially bed rest, also impairs pulmonary function. Tidal volume is diminished; atelectasis may occur, which, when combined with the supine position, predisposes to developing aspiration pneumonia.

Gastrointestinal and genitourinary problems are likewise influenced by immobility. Constipation and fecal impaction may occur because of decreased mobility and inappropriate positioning to optimize defecation. Urinary retention can result from inability to void lying down and/or rectal impaction impairing the flow of urine. These conditions and their management are discussed in Chapter 8. Immobility and spending more time in sedentary activity has also been associated with all-cause mortality (Bankoski et al., 2011).

Assessing Immobile Patients

Several aspects of the history and physical examination are important in assessing immobile patients (Table 10–3). Focused histories should address the intrapersonal aspect as well as the environmental issues associated with immobility. It is important to explore the underlying cause, or perceived cause, of the immobility on the part of the patient and caregiver. Specific contributing factors to explore include medical conditions, treatments (eg, medications, associated treatments such as intravenous lines), pain, psychological (eg, mood and fear) state, and motivational factors. Nutrition status, particularly protein levels and evaluation of 25-hydroxy vitamin D, is particularly useful to consider when evaluating the older patient because these have been associated with muscle weakness, poor physical performance, balance problems, and falls. An assessment of the environment is critical and should include both the patient’s physical and social environment (particularly caregiving interactions). Any and all of these factors can decrease the individual’s willingness to engage in activities. Although a comprehensive assessment is critical, other members of the health-care team (eg, social work, physical therapy) can facilitate these evaluations and provide at least an aspect of that assessment.

History Nature and duration of disabilities causing immobility Medical conditions contributing to immobility Pain Drugs that can affect mobility Motivation and other psychological factors Environment Physical examination Skin Cardiopulmonary status Musculoskeletal assessment Muscle tone and strength (see Table 10–4) Joint range of motion Foot deformities and lesions Neurological deficits Focal weakness Sensory and perceptual evaluation Levels of mobility Bed mobility Ability to transfer (bed to chair) Wheelchair mobility Standing balance Gait (see Chap. 9) Pain with movement |

In addition to the potential causes of immobility, the impact of immobility in older adults must always be considered. A comprehensive skin assessment should be done with a particular focus on bony prominences and areas of pressure against the bed, chair, splint, shoe, or any type of immobilizing device. Evaluation of lower extremities among those with known arterial insufficiency is critical. Cardiopulmonary status, especially intravascular volume, and postural changes in blood pressure and pulse are important to consider, particularly as these may further limit mobility. A detailed musculoskeletal examination, including evaluation of muscle tone and strength, evaluation of joint range of motion, and assessment of podiatric problems that may cause pain, should be performed. Standardized and repeated measures of muscle strength can be helpful in gauging a patient’s progress (Table 10–4). The neurological examination should identify focal weakness as well as cognitive, sensory, and perceptual problems that can impair mobility and influence rehabilitative efforts.

0 = Flaccid |

1 = Trace/slight contractility but no movement |

2 = Weak with movement possible when gravity is eliminated |

3 = Fair movement against gravity but not against resistance |

4 = Good with movement against gravity with some resistance |

5 = Normal with movement against gravity and some resistance |

Most importantly, the patient’s function and mobility should be assessed and reevaluated on an ongoing basis. Assessments should include bed mobility; transfers, including toilet transfers; and ambulation and stair climbing (see Table 10–3). Pain, fear, resistance to activity, and endurance should simultaneously be considered during these evaluations. As previously noted, other members of the health-care team (eg, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nursing) are skilled in completion of these assessments and are critical to the comprehensive evaluation of the patient.

Management of Immobility

The goal in the management of any older adult is to optimize function and mobility to the individual’s highest level. Medical management is central to assuring this goal because optimal management of underlying acute and chronic disease must be addressed to assure success. It is beyond the scope of this text to detail the management of all conditions associated with immobility in older adults; however, important general principles of the management of the most common of these conditions are reviewed. Brief sections at the end of the chapter provide an overview of key principles in the management of pain and the rehabilitation of geriatric patients.

Arthritis includes a heterogeneous group of related joint disorders that have a variety of causes such as metabolism, joint malformation, joint trauma, or joint damage. The pathology of osteoarthritis (OA) is characterized by cartilage destruction with subsequent joint space loss, osteophyte formation, and subchondral sclerosis. OA is the most common joint disease among older adults and is the major cause of knee, hip, and back pain. OA is not, by definition, inflammatory, although hypertrophy of synovium and accumulation of joint effusions are typical. It is currently believed that the pathogenesis of OA progression revolves around a complex interplay of numerous factors: chondrocyte regulation of the extracellular matrix, genetic influences, local mechanical factors, and inflammation.

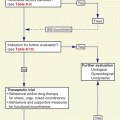

Plain film radiography has been the main diagnostic modality for assessing the severity and progression of OA. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound, however, have been noted to be more accurate and comprehensive measures of joint changes. Once diagnosed, a wide variety of modalities can be used to treat OA as well as other painful musculoskeletal conditions. Treatment can be separated into three different categories: nonpharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical. Nonpharmacological management should be the focus of interventions and include weight loss, physical therapy to strengthen related musculature, use of local ice and heat, acupuncture, and use of exercise programs to maintain strength and function.

Pharmacological management is targeted toward symptomatic relief and includes use of analgesics (discussed further later), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), intraocular steroid injections, and viscosupplementation. In addition, topical nonsteroidals, arthroscopic irrigation, acupuncture, and nutraceuticals, which are a combination of pharmaceutical and nutritional supplements, have also been used. The most common nutraceuticals include glucosamine and chondroitin (Simon et al., 2010) Although there may be a placebo effect resulting in benefit to patients using glucosamine and chondroitin, there is no evidence of a significant improvement in pain (Simon et al., 2010). Likewise there is no evidence that vitamin D decreases pain or facilitates repair of structural damage among individuals with OA (Felson et al., 2007). Arthroscopic interventions have been recommended for situations in which there is known inflammation and when other noninvasive interventions have failed. Options include debridement and lavage, osteotomy, cartilage transplant, and arthroplasty. There is little evidence, however, to support their efficacy (Moseley et al., 2002). Joint replacement should be reserved for individuals with severe symptomatic disease who do not respond to more conservative interventions. Patients referred for joint replacement should have stable medical conditions and be encouraged to lose weight and strengthen relevant muscles before the procedure. Optimal management often involves the use of multiple treatment modalities, and the best combination of treatments will vary from patient to patient.

Treating arthritis optimally requires a differential diagnosis because there are multiple different types of arthritic conditions and treatments may vary. For example, polymyalgia rheumatica is a common musculoskeletal problem for older women with symptoms that include weight loss; fever; muscle pain; aching of the neck, shoulder, and hip; and morning stiffness. Treatment involves use of steroids, such as prednisone, although methotrexate has been used as a corticosteroid-sparing agent and may be useful for patients with frequent disease relapses and/or corticosteroid- related toxicity. Conversely, infliximab has not been shown to be beneficial in terms of pain management or disease progression and thus is not currently recommended (Hernández-Rodríguez et al., 2009). Because of the close association between polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis, any symptoms suggestive of involvement of the temporal artery—headache, jaw claudication, recent changes in vision—especially when the sedimentation rate is very high (>75 mm/h), should prompt consideration of temporal artery biopsy. Acute treatment of temporal arteritis with high-dose steroids is needed to prevent blindness. The history and physical examination can be helpful in differentiating OA from inflammatory arthritis (Table 10–5); however, other procedures are often essential.

Clinical feature | Osteoarthritis | Inflammatory arthritis |

|---|---|---|

Duration of stiffness | Minutes | Hours |

Pain | Usually with activity | Occurs even at rest and at night |

Fatigue | Unusual | Common |

Swelling | Common but little synovial reaction | Very common, with synovial proliferation and thickening |

Erythema and warmth | Unusual | Common |

Gout, one of the oldest recognized forms of arthritis, is characterized by intra-articular monosodium urate crystals. Gout generally presents as acute, affecting the first metatarsal phalangeal joint, mid foot, or ankle, although the knee, elbow, or wrist can also be involved. Tophi, which are subcutaneous urate deposits on extensor surfaces, can develop in later phases of the disease and are sometimes confused with rheumatoid arthritis and associated nodules. Radiographs may reveal well-defined gouty erosions in or around joints. Some patients will have elevated uric acid levels. The definitive diagnosis of gout is established by observing the presence of needle-shaped crystals in the involved joint. The goal of treatment is to terminate the acute attack and then prevent future attacks by considering underlying causes (eg, considering hypouricemic therapy). The acute phase of gout should be managed using short-term NSAIDs, colchicine, corticotrophin, and corticosteroids. Treatment choices should be based on patient comorbidities (eg, renal function, gastrointestinal disease). Treatment to decrease uric acid levels should not be initiated during the acute phase because drugs such as allopurinol or probenecid may exacerbate the acute attack. Due to renal changes associated with aging, allopurinol is recommended over probenecid in older individuals. Colchicine can be used for acute management as well as for prophylaxis. More recently, interleukin inhibitors have been found to be effective in the management of gout, particularly for individuals who cannot tolerate allopurinol (Stamp and Jordan, 2011).

In addition to making specific diagnoses of rheumatological disorders whenever possible, careful physical examination can detect treatable nonarticular conditions such as tendinitis and bursitis. Bicipital tendinitis and olecranon and trochanteric bursitis are common in geriatric patients. Dramatic relief from pain and disability from these conditions can be achieved by local treatments such as the injection of steroids.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is another common musculoskeletal disorder among older adults and can be confused for gout, rheumatoid arthritis, or pseudogout. Carpal tunnel syndrome involves the entrapment of the median nerve where it passes through the carpal tunnel of the wrist and thereby causes nocturnal hand pain, numbness, and tingling affecting the median nerve distribution in the hand. Further atrophy of the thenar eminence can develop when there has been persistent nerve compression. Nerve conduction studies are needed to make the diagnosis, and surgical intervention is often needed to relieve the nerve compression. For more conservative interventions, cock-up wrist splints, usually worn at night, isometric flexion exercises of metacarpal phalangeal joints, and steroid injections have been implemented.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree