Figure 6.1

(a) Resorptive change is seen affecting the proximal and middle phalanges of the fifth toe with focal lucency at the base of the proximal phalanx of the second toe. Features are consistent with osteomyelitis. There is also established arthropathy affecting the first tarsometatarsal joint. (b) In the same patient after treatment, remodelling and sclerosis of the second metatarsal with cortical erosion of the base of the proximal phalanx is seen consistent with chronic osteomyelitis

Figure 6.2

In this patient with cellulitis there is extensive soft-tissue gas along the medial aspect of the foot and ankle. Fracture of the second toe is also demonstrated

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most accurate and next most appropriate imaging tool for assessment of suspected osteomyelitis where plain radiographic findings have been equivocal. In addition to bony abnormalities, MRI provides exquisite detail about the soft tissues and has a reported sensitivity of 90 % and specificity of 82.5 % for the detection of osteomyelitis [2]. MRI provides additional anatomical definition of soft-tissue infection, sinus tracts, abscess formation, joint effusion and necrosis. The characteristic MRI features of osteomyelitis are a diffuse decreased T1-weighted and increased T2-weighted signal intensity of the affected bone, with contrast enhancement (Fig. 6.3). There is often replacement of intramedullary fat around the affected bone and a sinus tract to an ulcer. Secondary findings of an abscess may be identified by its high signal intensity on fat-suppressed imaging with high signal intensity rim-enhancement on post-contrast T1-weighted images.

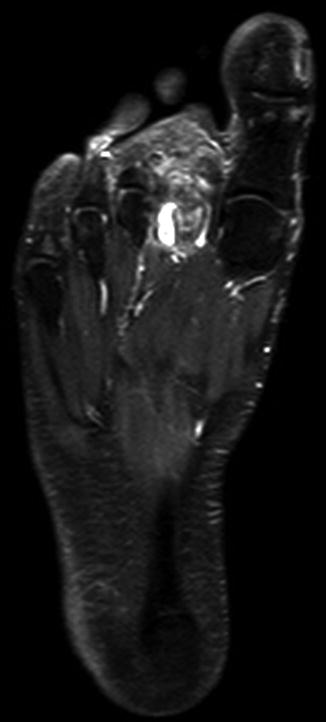

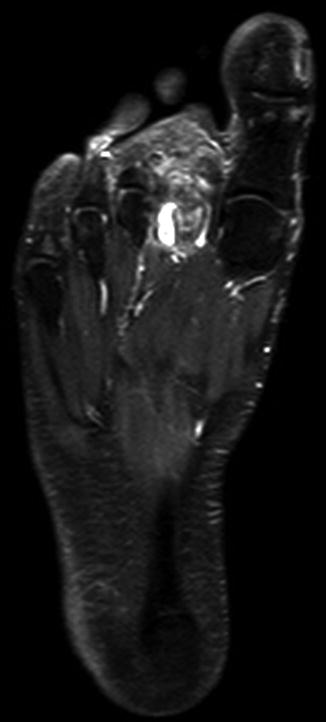

Figure 6.3

MRI (T1-weighted sequence with fat saturation and intravenous contrast) shows bone marrow and soft-tissue oedema centred on the second metatarsal, which enhance with contrast

Features favouring neuropathic arthropathy are the involvement of multiple joints, subchondral cysts and intra-articular loose bodies. In the early or sub-acute stage of neuropathic arthropathy, subchondral bone marrow oedema and bone resorption is the common initial finding. In the late or chronic stage, there is usually established subluxation and dislocation but with minimal bone marrow oedema. In distinction to osteomyelitis, the subcutaneous tissues are usually not involved. However, a mixture of findings can be encountered in patients with pre-existing neuropathic arthropathy who go on to develop infection.

Prior to performing the MRI, it is useful to mark any cutaneous defect so that any sinus tract can be followed and the bone marrow immediately beneath it may be evaluated. MRI is of particular value, not only in determining the need for surgical intervention, but in planning the surgical approach. Magnetic resonance angiography is not routinely performed in patients with diabetic foot complications but is undertaken for the assessment of peripheral vascular disease and in planning revascularisation for critical limb ischaemia. This is described in greater detail below. The potential limitations of MRI relate to its lack of availability in some hospitals and the need for expert interpretation by a specialist in musculoskeletal radiology. Contraindications to MRI include most cochlear implants, older types of cardiac pacemakers, orbital metallic foreign bodies and some surgical implants and prostheses. When MRI is contraindicated alternatives such as nuclear medicine scintigraphy or PET/CT should be considered.

Nuclear Medicine Scintigraphy

The practice of isotope imaging in assessing diabetic foot complications varies considerably and may not be available in some centres. Its principal value lies in the ability to discriminate between infection and other causes of inflammation, but these techniques are limited by a relative lack of resolution and anatomical detail. A number of techniques are utilised, including Technetium (Tc) -labelled bone scans, leukocyte-labelled and anti-granulocyte antibody-labelled scintigraphy and bone marrow scintigraphy. The triple-phase 99mTc-MDP (methylene diphosphonate) bone scan alone is of limited value in assessing diabetic foot complications because although it has high sensitivity in demonstrating areas of high metabolic activity, its specificity is significantly reduced in the presence of any other abnormalities such as fractures, arthropathy, tumour or recent surgery [3]. A four-phase bone scan in which an additional 24-h static image is acquired, is not routinely recommended as it does not increase the specificity of the study for the detection of osteomyelitis.

The triple-phase bone scan is more useful when utilised in conjunction with the Indium-111 or 99mTc-HMPAO (hexamethylpropyleneamineoxime) leukocyte-labelled study to diagnose and differentiate arthropathy from osteomyelitis. If the initial bone scan is negative, osteomyelitis is unlikely. When the bone scan is positive, the leukocyte-labelled study is performed to confirm or exclude osteomyelitis. However, the leukocyte-labelled study may be positive in the early stages of neuropathic arthropathy, due to reactive joint effusion from peri-articular microfractures. In such cases, if a follow-up scan shows a reduction in leukocyte accumulation, the changes are more likely to be due to arthropathy rather than osteomyelitis. The use of alternative techniques such as bone marrow and anti-granulocyte scintigraphy are likely to be restricted to specialist centres.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree