T

Primary tumor

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

Carcinoma in situ

Ta

Noninvasive verrucous carcinoma, not associated with destructive invasion

T1

Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue

T1a

Without lymphovascular invasion and is not poorly differentiated or undifferentiated (T1 G1–2)

T1b

With lymphovascular invasion or poorly differentiated or undifferentiated (T1 G3–4)

T2

Tumor invades corpus spongiosum/corpora cavernosa

T3

Tumor invades urethra

T4

Tumor invades adjacent other structures

N

Regional lymph nodes

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No. palpable gold visibly enlarged inguinal lymph node

N1

Palpable mobile unilateral inguinal lymph node

N2

Palpable mobile multiple or bilateral inguinal lymph nodes

N3

Fixed inguinal nodal mass or pelvic lymphadenopathy unilateral or bilateral

M

Remote metastases

M0

No remote metastasis

M1

Remote metastasis

The low incidence of penile cancer and the fact that it involves a highly symbolic organ are responsible for (1) poor medical recognition of the diagnosis of SCC of the penis, premalignant lesions, and local and regional staging and (2) delayed diagnosis due to the patient’s fears concerning the impact on his sexuality.

Early diagnosis of the primary tumor should allow conservative treatment, particularly for tumors of the glans, and simplify the assessment of inguinal lymph node status.

Imaging and Clinical Staging of the Primary Tumor

The primary tumor can arise anywhere on the penis, but the most common sites are the glans and foreskin. Primary tumors of the body of the penis are rare (<2 %), while secondary tumors, localized in the corpus cavernosum, reflect systemic disease.

The appearance of a tumor of the penis can constitute a warning sign for the patient in the form of induration, increased size, or a papillary or ulcerated lesion. The presence of acquired phimosis may hide a primary tumor that can progress unnoticed. Subsequent signs then consist of purulent discharge, urgency, pain, bleeding, or erosion of the tumor through the foreskin.

Physical Examination

During the first consultation, palpation of the penis is essential to locate the primary tumor (glans, foreskin, corpus cavernosum), define the limits of the tumor in relation to other structures (corpus spongiosum, corpus cavernosum, urethra), and determine the size and numbers of tumors and their morphology (flat, papillary, nodular, or ulceration) (Fig. 6.1). This clinical assessment may be distorted by tumor infection and peripheral edema of the tumor or foreskin, suggesting infiltration. The inaccurate clinical staging of the primary tumor has been estimated to concern 26 % of patients, with understaging in 10 % and overstaging in 16 % of cases [15].

Fig. 6.1

Tumors of the penis. (a) Clinical stage T2 limited to the glans. (b) Clinical stage T2 with invasion of the corpus cavernosum. (c) Clinical stage T3 with invasion of the corpora cavernosum and urethra

The presence of tumor invasion of the corpus cavernosum is a major prognostic factor for survival; in the majority of cases, the presence and extent of inguinal lymph node metastasis contraindicate conservative surgical techniques of the glans.

The 2009 TNM classification, based on clinical signs, is not sufficient for the assessment of prognosis and survival of the patients, as several studies have shown similar survival for stage cT3 or higher compared to stage cT2 [24, 28]. Stage cT3 corresponds to invasion of the urethra, but the prognosis of the tumors of the glans with invasion of only distal urethra is better than that of tumors with invading the corpus cavernosum.

Penile Ultrasound

7.5 or 10 MHz ultrasound probes are useful for large tumors involving the glans to define the anatomical relations with the corpora cavernosum and urethra [16] but only when these relations cannot be determined on physical examination [29] (Fig. 6.2). Penile ultrasound can demonstrate invasion of the corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum, and tunica albuginea infiltration is visualized as interruption of the thin echogenic line of the tunica.

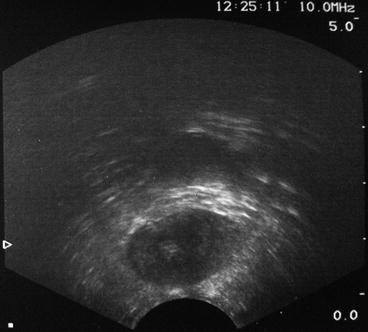

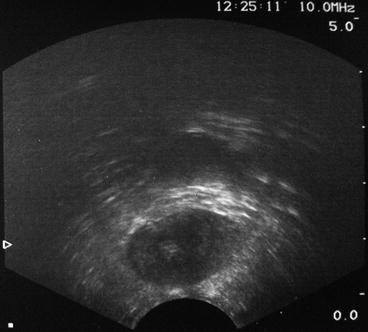

Fig. 6.2

Ultrasound using a 10 MHz probe. Distal tumor of the glans invading the navicular fossa and distal urethra

However, this examination is difficult to interpret due to the inflammation and/or infection frequently associated with the primary tumor and in the case of acquired phimosis secondary to large tumors. These tumors may also be hyperechoic and hypoechoic or present mixed echogenicity.

Only one study showed that tumors confined to the glans were often understaged on physical examination, in contrast with tumors invading the body of the penis, and that ultrasound was more reliable than physical examination [1].

Penile MRI

Staging of tumors of the glans and foreskin by MRI is designed to demonstrate infiltration of the tunica albuginea of the corpus cavernosum or the urethra (Figs. 6.3 and 6.4). Tumors are hypointense on T1- and T2-weighted sequences and are gadolinium enhanced. The only way to obtain reliable images correlated with the pathological stage is to perform MRI during erection or after intracavernosal injection of 10 μg of prostaglandin E1.

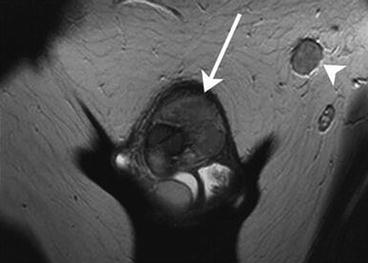

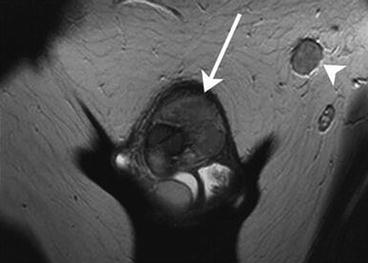

Fig. 6.3

MRI of the penis. Stage T2 tumor of the glans with invasion of the tunica albuginea of corpus cavernosum (arrow) and the presence of a left inguinal node (arrowhead)

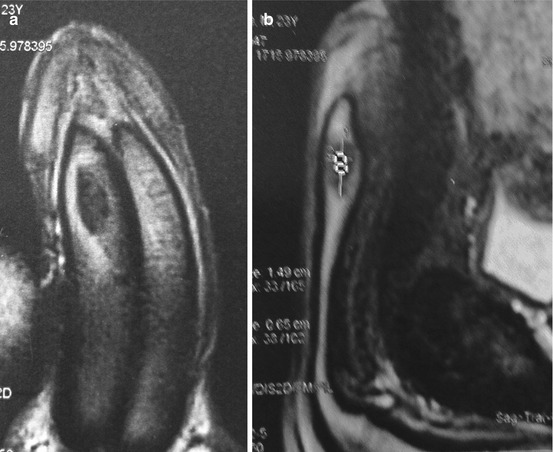

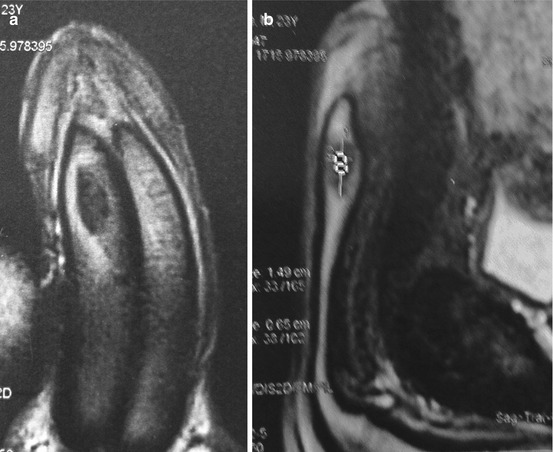

Fig. 6.4

MRI of the penis. Large stage T2 tumor of the glans with extensive invasion of the corpora cavernosa (arrow) and urethra (arrowhead)

The routine indications for MRI are being extended to improve the selection of patients eligible for penile sparing surgery (local excision, partial or total glansectomy) and brachytherapy [18]. Errors of interpretation are essentially related to tumor infection or secondary to phimosis and the absence of erection.

In tumors of the penile body, MRI is necessary to define tumor margins with respect to the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosum and to detect other penile sire sites (Fig. 6.5).

Fig. 6.5

(a, b) MRI of a primary tumor of the corpus cavernosum without invasion of the tunica albuginea

Penile Biopsy

Apart from locally advanced tumors for which the diagnosis is obvious, lesions suspicious of malignancy, involving the glans and/or refractory to treatment, require diagnostic biopsy for histological examination.

Small superficial biopsies are difficult to analyze [41]. It is preferable to perform a biopsy–excision of the tumor, which provides a maximum of information concerning the histological type, cytological grade, growth patterns, tumor thickness (±3 mm), the presence of lymphatic or vascular embolization, and surgical margins. All this information is useful for treatment and prognosis, especially as tumor subtypes with different prognoses have been recently reported [3].

Imaging and Clinical Staging for Regional Lymph Nodes

Penile cancer essentially spreads via lymphatic dissemination, while vascular dissemination is less common. The first draining lymph nodes are bilateral inguinal lymph nodes [5]. A recent study visualized the lymphatic drainage of penile cancer by single photon emission computed tomography–computed tomography (SPECT-CT), showing that the first inguinal draining node was located in the superior and central quadrants of superficial inguinal lymph nodes, according to Daseler’s description, particularly the medial superior quadrant [25]. No direct drainage of the penis to the two inferior quadrants of superficial inguinal lymph nodes and no direct drainage to pelvic lymph nodes were observed [25].

Physical Examination

The presence of palpable superficial inguinal lymph nodes must be determined at the first visit. Palpable inguinal lymph nodes are present in 28–64 % of patients with penile cancer at presentation. Nodal metastases are found in about one-half of these cases, while palpable nodes are due to an inflammatory reaction in the remaining cases. About 75 % of patients with palpable inguinal lymph nodes have unilateral invasion, and 25 % have bilateral nodal invasion [8, 14, 17].

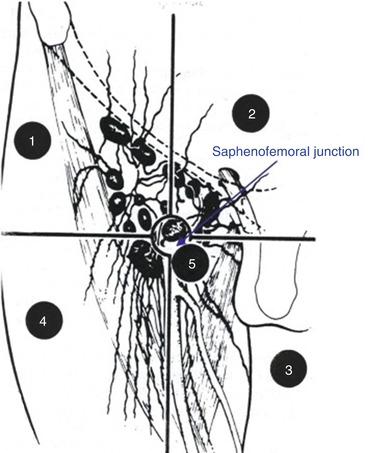

The first draining lymph nodes must be thoroughly examined on both sides, with particular attention to the superior quadrants of superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Palpation and ultrasound should therefore both focus on the quadrants above the groin, as the medial superior group lies just lateral to the ipsilateral spermatic cord. The central group, opposite the saphenous arch, is situated in the inguinal crease (Fig. 6.6).

Fig. 6.6

Representation of superficial inguinal lymph node quadrants according to Daseler [5]. The upper quadrants, above the inguinal crease, are zones 1 and 2. Zone 3, next the saphenous arch, represents the central quadrant

In the presence of palpable lymph nodes, physical examination of the inguinal region should note the following characteristics: number, site (unilateral or bilateral), dimensions, mobility or fixation, relations to other structures (skin, Cooper’s ligament), and edema of the penis, scrotum, and/or legs.

Unfortunately, physical examination of inguinal lymph nodes cannot reliably predict the presence of lymph node metastasis, as it has a sensitivity and specificity of 90 and 21 % compared to pathological findings, respectively [15]. Some authors have proposed a course of antibiotics for patients with suspected inflammatory lymph nodes in order to improve the accuracy of physical examination. However, a long course of antibiotic therapy would delay the diagnosis, which would have a negative impact on prognosis. Imaging is useful to distinguish inflammatory and metastatic lymph nodes.

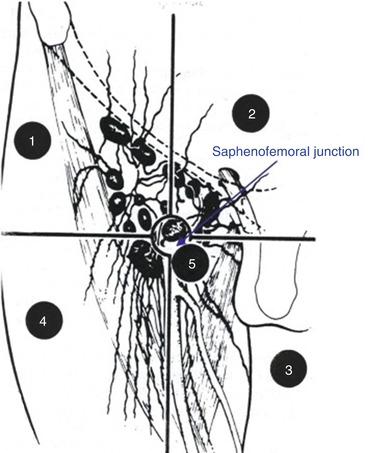

Inguinal Ultrasound Using a 7.5 MHZ or 10 MHz Probe

The role of inguinal ultrasound is to identify metastatic lymph nodes, especially in the superior quadrants and in obese patients in whom physical examination can be particularly difficult.

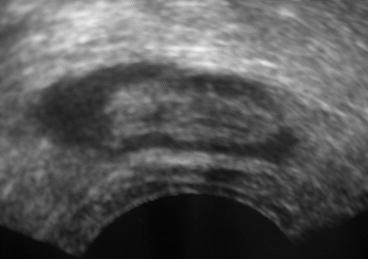

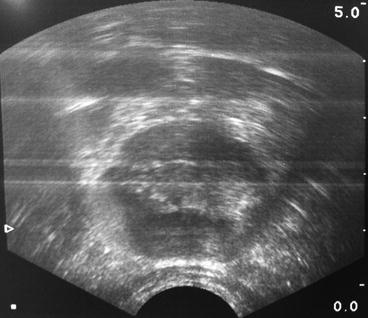

High-resolution probes allow detailed analysis of inguinal lymph nodes, and features suggestive of tumor invasion include enlarged node, abnormal shape, short-/long-axis ratio <2, eccentric cortical hypertrophy, the absence of echogenic hilum, and hypoechogenicity due to a necrotic zone (Figs. 6.7, 6.8, and 6.9). Pulsed Doppler is also used to demonstrate increased density of the peripheral blood supply of the node [6].

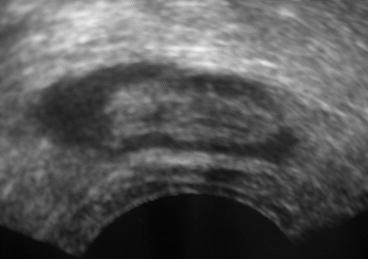

Fig. 6.7

Inguinal ultrasound using a 10 MHz probe. Normal inguinal lymph node homogeneous hypoechoic cortex with intact contours and hyperechoic hilum

Fig. 6.8

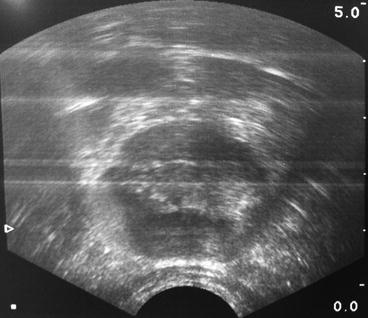

Inguinal ultrasound using a 10 MHz probe. Enlarged node with eccentric cortical hypertrophy suggestive of metastasis

Fig. 6.9

Inguinal ultrasound using a 10 MHz probe. Enlarged node with loss of the hyperechoic hilum suggestive of metastasis

However, ultrasound alone cannot detect micrometastatic inguinal lymph nodes.

Lymph Node Cytology

Inguinal ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) should be systematically performed in patients with clinically palpable lymph nodes and/or abnormal lymph nodes on ultrasound examination, especially in the presence of zones of tumor necrosis. This percutaneous procedure can be performed during physical examination with an intradermal needle (skin–node distance less than 2 cm). The lymph node material obtained is smeared onto a slide, dried, and then sent directly for cytological and/or histological examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree