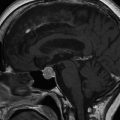

Fig. 17.1

Cortisol day curve performed after first episode of severe hypoglycaemia

Unfortunately, 6 months later she experienced a further episode of severe hypoglycaemia at work, involving a further blackout and collapse, again associated with a generalised tonic-clonic seizure. Her capillary blood glucose, measured immediately after the seizure, was 11 mmol/l but it had fallen to 3.2 mmol/l by the time she arrived at hospital. It was presumed that this seizure had also been precipitated by hypoglycaemia with no preceding warning symptoms. Neuroradiological investigation with CT and MRI scans of the brain, showed no abnormalities and review by a neurologist supported the presumption that this had been another hypoglycaemia-induced seizure. The patient informed the DVLA of this second severe hypoglycaemia episode and her driving licence was revoked.

She was reviewed within 2 weeks in the diabetes clinic and was noted to have a capillary blood glucose of 2.8 mmol/l without any symptoms of hypoglycaemia being experienced. Her insulin to carbohydrate ratio was reduced to 1 unit for 12 g. The patient had restored her hydrocortisone dose to 20 + 10 mg as she was concerned that the previous reduction in steroid replacement therapy may have contributed to the further episode of severe hypoglycaemia. As her insulin requirements had increased, her weight had stabilised and she now weighed 66.5 kg. She was considered to have developed impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia.

Question8. How can you assess awareness of hypoglycaemia in an individual patient?

Various methods can be used to assess awareness of hypoglycaemia [7, 8]. The method by Clarke et al. [8] consists of eight questions to document the individual’s exposure to hypoglycaemia along with their glycaemic threshold for the development of hypoglycaemic symptoms and the nature of these symptoms, with a score of 4 or above suggesting impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia. The method by Gold and colleagues [7] poses the question “do you know when your hypos are commencing?” The subject gives their answer on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 represents “always aware” and 7 represents “never aware.” A score of 4 or above suggests impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia. In a 1-year prospective study utilising this method, the incidence of hypoglycaemia in 29 patients with impaired awareness was 2.8 episodes per person per year with a prevalence of 66 %. By contrast, the incidence in the normal awareness group (n = 31) was only 0.5 episodes per person per year with a prevalence of 26 % [7]. This heightened risk of severe hypoglycaemia highlights the importance of identifying impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia.

Very good concordance has been found between the Clarke and Gold methods [9]. The prevalence of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia in that study [9] using the Clarke and Gold methods was similar to the prevalence observed in previous population studies, indicating a prevalence of 20–27 % in unselected individuals with insulin-treated diabetes [10–13].

After a further 6 months the patient sustained another episode of severe hypoglycaemia with no warning during a short walk. Specialist review confirmed that she had little understanding of carbohydrate counting and had been adopting a reactive approach to her diabetes by taking corrective doses in response to hyperglycaemia rather than pre-empting the dose required according to carbohydrate intake and exercise. Consequently, significant swings were noted in her blood glucose readings. The diabetes nurse specialists attempted re-education but she maintained that she could not comprehend carbohydrate counting and attempting to pursue this made her feel very anxious. Her weight had now almost reached her premorbid baseline at 70 kg and HbA1c was 72 mmol/mol (8.9 %). Because of her past experience of nocturnal hypoglycaemia she had reduced her basal insulin analogue dose to just 6 units. Consequently, fasting blood glucose readings were consistently in double figures and she was compensating by taking large doses of rapid-acting analogue with her breakfast, which frequently resulted in hypoglycaemia by late morning. A programme of diabetes nurse follow-up was instigated to titrate the dose of her basal insulin and reduce the large doses of rapid-acting insulin being injected at breakfast. The availability of glucagon at home was discussed but as she lived alone she felt that this would not be useful. The possibility that over-treatment with hydrocortisone might be contributing to some of the hyperglycaemic spikes was met with resistance by the patient, who said that she was terrified of reducing her hydrocortisone again in case this provoked another episode of severe hypoglycaemia.

Despite these measures and despite frequent blood glucose monitoring, she continued to suffer episodic severe hypoglycaemia without warning symptoms. A hypoglycaemia-induced seizure in a supermarket just before lunch required the previous proposal to reduce her breakfast rapid-acting insulin analogue to be reiterated, with a further reduction in her morning dose. About 6 months later she had a blackout and collapsed in a theatre despite having eaten beforehand. She was treated with glucagon by emergency paramedical staff. One year later she suffered a further episode of severe hypoglycaemia causing loss of consciousness in the cinema. Despite her mealtime insulin doses having been reduced, she had taken 20 units of rapid-acting analogue for a meal that contained much less than 200 g of carbohydrate. It was apparent that attempts at re-education had not been successful.

Question9. What other options could be considered to reduce the frequency of her recurrent severe hypoglycaemia?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree