Hürthle cell carcinoma is a rare subtype of well-differentiated thyroid cancer representing 3% to 4% of all thyroid malignancies.1 First described by Max Askanazy in 1898 and then erroneously attributed to Karl Hürthle 30 years later, Hürthle cell carcinoma continues to perplex even experienced endocrine surgeons and surgical oncologists due to the rarity of disease as well as the somewhat variable natural history.

Classically, Hürthle cell carcinoma was thought to represent a more malevolent form of well-differentiated thyroid cancer given its multifocality and high incidence of metastasis at the time of presentation. However, more precise molecular, genetic, and histopathologic characterization of Hürthle cell tumors has led us to recognize that while Hürthle cell carcinoma carries a worse prognosis as compared to papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), the prognosis of Hürthle cell carcinoma in fact mirrors that of follicular thyroid carcinoma.

Patients with Hürthle cell carcinoma are typically euthyroid women between 50 to 70 years of age. As in most cases of well-differentiated thyroid cancer, women outnumber men by approximately 3 to 1.2,3 While bilateral or multifocal disease is commonly identified at presentation, the vast majority of Hürthle cell carcinoma patients present with a single, palpable, nontender thyroid nodule. Approximately one-third of Hürthle cell carcinoma patients have nodal (10% to 25%) or distant (10% to 29%) metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.4,5

The risk factors for Hürthle cell carcinoma are consistent with those of other well-differentiated thyroid cancers and include childhood head and neck radiation and/or a family history of thyroid cancer. Interestingly, in contrast to follicular thyroid carcinoma, Hürthle cell carcinoma is more common in iodine-rich areas as opposed to regions where iodine deficiency is seen. Previous radiation exposure correlates not only with increased bilaterality and multicentricity of Hürthle cell carcinoma at presentation but also with an increased incidence of contralateral, non-Hürthle cell carcinoma. To date, no genetic syndromes have been reported to be associated with Hürthle cell cancer.

Size is an important risk factor for malignancy in Hürthle cell tumors. Tumors greater than 4 cm are reported to be malignant in 44% to 65% of cases as compared with only 10% to 13% in tumors less than 4 cm in size. Advanced age is also a risk factor, with patients over 50 years of age noted to be at higher risk for malignant disease.6,7

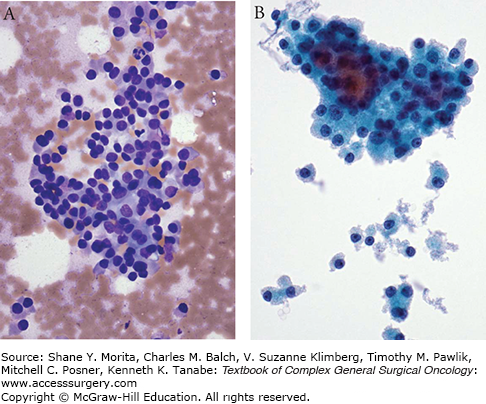

Hürthle cells are large, polygonal cells characterized by an intensely eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm with abundant mitochondria and a prominent nucleolus (Fig. 36-1A, B). They are derived from the follicular epithelium and are seen in both benign and malignant disease. In terms of benign disease, Hürthle cells are classically detected in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as well as in Graves’ disease. Patients with multinodular goiter or those who have undergone thyroid irradiation or chemotherapy also commonly harbor benign nests of Hürthle cells. These “inflammatory” Hürthle cells can be pathologically distinguished from noninflammatory disease by the presence of intralesional lymphocytes and the absence of a complete capsule.

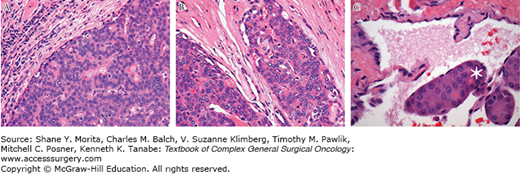

Hürthle cell tumors are pathologically defined as encapsulated lesions composed of at least 75% Hürthle cells (Fig. 36-2A). They may be either benign or malignant. Malignant tumors are characterized by capsular or vascular invasion which can be further described as minimally invasive (Fig. 36-2B) or widely invasive (Fig. 36-2C) depending upon the extent of vascular or capsular invasion. A precise definition of minimally invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma remains somewhat controversial. Current practice broadly categorizes minimally invasive disease as having less than four foci of capsular or vascular invasion and widely invasive disease as having more than four foci of invasion.8 More conservative pathologists define minimally invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma as having a single focus of vascular invasion.9

FIGURE 36-2

Histopathology by hematoxylin and eosin histopathological staining demonstrating (A) minimally invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma with focus of extracapsular invasion; (B) Hürthle cell adenoma lacking evidence of capsular or vascular invasion; and (C) Hürthle cell carcinoma with vascular invasion. Asterisk delineates focus of vascular invasion. (Used with permission from William C. Faquin, MD, PhD.)

Considerable work over the past decade has been aimed toward improving our understanding of Hürthle cell carcinoma as a unique subtype of well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Recently, a large-scale analysis directly compared the gene expression profiles of Hürthle cell carcinoma to papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. This group looked at variations in mutation and copy number alteration between each subtype of well-differentiated thyroid cancer and found that Hürthle, papillary, and follicular carcinomas have distinct and specific molecular signatures. In-depth analysis of Hürthle cell tumors in particular revealed that benign adenomas, and minimally and widely invasive Hürthle cell carcinomas each upregulate unique cell signaling pathways. Specifically, the PIK3CA-Akt-mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin pathways are upregulated in widely invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma as compared to minimally invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma or benign disease.

While Hürthle cell cancer has long been considered a subtype of follicular thyroid cancer, more recently a papillary variant of Hürthle cell carcinoma has also been described.10,11 Papillary variant Hürthle cell carcinoma harbors the ret/PTC gene rearrangement classically seen in PTC. The clinical course of papillary variant Hürthle cell carcinoma is similar to that of PTC with reduced distant metastatic disease and a higher incidence of regional nodal metastasis characteristic of lymphatic rather than hematogenous spread. Interestingly, ret/PTC mutations have also been identified as a unique molecular marker of the very rare Hürthle cell adenoma that progresses to malignancy.

Taken together, the identification of multiple variants of Hürthle cell tumors is particularly pertinent when considering the controversy with respect to disease prognosis. We now recognize that the natural history of papillary variant Hürthle cell carcinoma resembles that of PTC. We know that the prognosis of minimally invasive and widely invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma falls along a spectrum of severity similar to that of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Where we once presumed that the development of Hürthle cell carcinoma occurred through a stepwise progression from adenoma, to minimally invasive, to widely invasive carcinoma, we must now consider that each tumor may result from a unique aberration in cell signaling ultimately resulting in variably indolent or aggressive disease. As we continue to advance our molecular understanding of Hürthle cell carcinoma with respect to the pathway-specific upregulation of each of the distinct subgroups of disease, we may begin to develop new, directed targets for therapy according to each subgroup.12

Patients with thyroid cancer typically present with a palpable thyroid nodule. The initial workup includes baseline thyroid function tests and ultrasound of the head and neck. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) helps to determine whether surgical intervention is indicated. There are six Bethesda categories of thyroid FNA cytology: (1) benign, (2) nondiagnostic, (3) suspicious for follicular or Hürthle cell neoplasm, (4) atypia or follicular lesion of undetermined significance, (5) suspicious for malignancy, and (6) malignant. Hürthle cells are identified by their characteristic granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm with prominent nucleoli on FNAB (Fig. 36-1A). Notably, the identification of Hürthle cells by FNAB does not guarantee the presence of malignant disease and patients should be cautioned against equating the presence of Hürthle cells to the diagnosis of cancer.

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with FNAB results that are suspicious for Hürthle cell neoplasms will require second-stage completion thyroidectomy for a final histopathologic diagnosis of Hürthle cell carcinoma. The remaining lesions are benign adenomas which do not require further intervention. To date, there are no clear cytologic factors that can help us distinguish benign from malignant disease. Intraoperative frozen sections are generally unreliable in visualizing vascular or capsular invasion and are therefore not recommended for real-time confirmation of Hürthle cell carcinoma.13 If FNAB results are indicative of a possible malignancy, further radiographic evaluation by ultrasound is a valuable method for assessing the thyroid gland as well as pathologically enlarged lymph nodes suspicious for metastasis. In select cases, where there are bulky or fixed lesions, or palpable lateral lymph nodes, CT/MRI is necessary for staging and operative planning. A role for fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in the diagnosis of Hürthle cell carcinoma remains to be clearly defined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree