Anal cancer is an increasingly common non–AIDS-defining cancer among individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It is associated with human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV16 is the most common genotype detected in anal cancers. The HPV types detected in anal cancer are included in the 9-valent vaccine. HPV vaccines have demonstrated efficacy in reducing anal precancerous lesions in HIV-infected individuals. Standard treatment has been fluorouracil and mitomycin (or cisplatin) plus radiation. Continued studies are needed to test new treatment strategies in HIV-infected patients with anal cancer to determine which treatment protocols provide the best therapeutic index.

Key points

- •

Anal cancer is preceded by precursor lesions; it is also almost always associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.

- •

The degree to which highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) prevents the development or progression of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) to anal cancer is not known.

- •

Both HPV infection and anal HSIL clearly occur in individuals well-controlled on HAART; overall the incidence of anal cancer is higher in the HAART era than the pre-HAART era.

- •

Individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who have anal cancer can receive similar treatment as HIV-negative individuals and achieve similar outcomes, but may require careful monitoring for toxicities.

- •

The use of a screening anal cytology in high-risk patients may lead to an earlier diagnosis of anal HSIL, and treatment of HSIL may decrease the risk for developing anal cancer.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, causes approximately 5% of all cancers in men and 10% of all cancers in women. Anal cancer is highly associated with HPV infection. Similar to cervical cancer, anal cancer is typically preceded by precursor lesions. In the general population, anal cancer is a relatively uncommon disease, only accounting for about 3% of all cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. However, the incidence of anal cancer is higher in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected population, and it is continuing to increase in the United States. About 80% of all anal cancers arise from the anal canal. In this article, we review the epidemiology of HPV-associated precancerous anal lesions and anal cancer in the HIV-infected population, and highlight some treatment-related issues.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, causes approximately 5% of all cancers in men and 10% of all cancers in women. Anal cancer is highly associated with HPV infection. Similar to cervical cancer, anal cancer is typically preceded by precursor lesions. In the general population, anal cancer is a relatively uncommon disease, only accounting for about 3% of all cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. However, the incidence of anal cancer is higher in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected population, and it is continuing to increase in the United States. About 80% of all anal cancers arise from the anal canal. In this article, we review the epidemiology of HPV-associated precancerous anal lesions and anal cancer in the HIV-infected population, and highlight some treatment-related issues.

Role of human papillomavirus infection

HPV is responsible for 100% of cervical cancers and 88% of anal cancers, with the majority caused by HPV16 or HPV18. Almost all (98%) anal cancer tumor specimens from men who were not exclusively heterosexual were positive for HPV, with 73% harboring HPV16. Although the majority of anal cancers associated with HPV are caused by type 16, HPV types 6, 11, and 31 account for 1.4% to 4.1%, and HPV18 accounts for 3.4% to 7%. HPV is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus with more than 100 different genotypes identified, of which at least 30 HPV genotypes are sexually transmitted and infect the squamous epithelium of the anogenital tract. HPV is highly prevalent in the young and sexually active population because HPV is transmitted through any sexual activity that involves skin-to-skin or skin-to-mucosa contact, including vaginal, anal, and oral sex. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals can transmit HPV to their sexual partners. Based on conservative assumptions and nationally representative data, more than 50% of sexually active women in the United States are estimated to have been infected by 1 or more genital HPV types at some point in their lifetime. Heterosexual HIV-negative adult men have also been shown to have an overall HPV prevalence of approximately 50%. Concordance of HPV infection between sexual partners is variable and ranges from 40% to 60%, which may be affected by length of sexual relationship, frequency of intercourse, condom use, and number of lifetime sexual partners. The overall transmission rate from 1 heterosexual partner to the other over a 6-month period is estimated to be 3.7 cases per 100 person-months. In a 12-month period, the probability for men to acquire a new genital HPV infection is estimated to be 0.29 to 0.39, which is similar to previous estimates for women.

The transformation of HPV-infected cells to cancer cells is a multistep process. HPV infects basal cells located in the epithelial transformation zone, a region that extends proximally from the squamocolumnar junction within the rectal columnar mucosa distally to the dentate line. In this area, there is active transition from columnar epithelium to squamous epithelium through the process of squamous metaplasia. Upon entry into the anal epithelium, HPV targets actively proliferating basal cells. E6 and E7 oncoproteins act to enhance cellular proliferation, resulting in increased numbers of infected cells and infectious virions. A spectrum of pathologic changes may occur as a result of HPV infection. Currently, it is believed that low-risk HPV types do not cause malignancy owing to weaker binding of their E6 and E7 to their target proteins, differences in promoter positioning and regulation, and pattern of mRNA splicing compared with E6 and E7 from the high-risk HPV types.

The terminology for HPV-associated squamous lesions of the lower anogenital tract has a long history marked by various diagnostic terms derived from multiple specialties. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) project aimed to create a histopathologic nomenclature system that reflects current knowledge of HPV biology. Current data support the 2-tiered system of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), which may be further qualified with the appropriate intraepithelial neoplasia terminology for specific location. Therefore, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions include condyloma and anal intraepithelial neoplasia 1, and are not considered to be precancerous. In contrast, HSIL includes p16-positive anal intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3. HSIL are considered to be the true cancer precursors.

Infection by multiple oncogenic types of HPV has been associated with a greater likelihood of anal HSIL in HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM). HIV-infected individuals, regardless of HIV risk factor, have a high prevalence of HPV infection and are at greater risk for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions, despite good virologic suppression of their HIV. In cross-sectional studies, anal HPV infection is almost universal among HIV-infected MSM, with reported prevalence estimates between 87% and 98%. A prospective cohort study to assess the natural history of anal HPV infection in HIV-infected MSM in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era showed that the incidence of any anal HPV infection and oncogenic anal HPV infection was 21.3 per 100 person-years and 13.3 per 100 person-years, respectively. Twenty percent of these men with an incident HPV infection also had more than 1 new HPV type detected during follow-up. Low CD4 counts are a risk factor for HIV-positive individuals developing anal squamous intraepithelial lesion. Palefsky and colleagues showed that, for HIV-positive men, having CD4 cell counts of less than 200/mm 3 was associated with a greater than 3-fold increased incidence of progression (based on cytology and/or biopsy) of normal or atypical epithelium to anal squamous intraepithelial lesions, or from anal low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to a higher grade lesion.

The role of human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS

It is estimated that there were approximately 37 million people worldwide living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2014, including about 1.2 million HIV-infected individuals in the United States. Approximately 1% of women and 28% of men with anal cancer also have HIV infection. Cancer is estimated to be responsible for more than one-third of all deaths in HIV-infected individuals. The immunosuppression associated with HIV infection reduces the ability to control oncogenic viral processes, which could explain the greater risk of infection-related cancer. This hypothesis is supported by a metaanalysis by Grulich and colleagues who compared cancer incidences in population-based cohort studies of persons with HIV infection and organ transplant recipients.

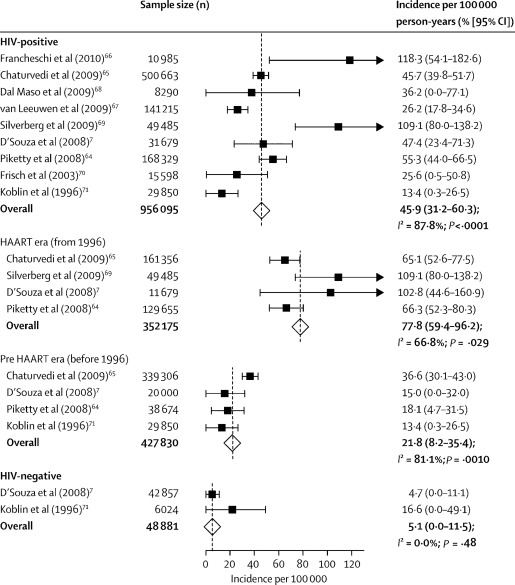

Before the availability of HAART, the estimated incidence of anal cancer among HIV-infected MSM was nearly 60-fold greater than in men in the general population. Since the advent of HAART, the incidence of malignancies associated with Epstein–Barr virus and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus has decreased in HIV-infected MSM. However, the incidence of HPV-associated anal cancer has increased ( Fig. 1 ). A recent report from the French 2010 survey of deaths in 82,000 HIV-infected patients evaluated the underlying causes of more than 700 deaths from 2000 to 2010. Non–AIDS-defining cancers were the cause of death in 26% of the patients in the most recent period, doubling from 2000. Of the 193 non–AIDS-defining cancers deaths, the commonest were bronchopulmonary malignancies (32%), hepatocellular carcinoma (17%), head and neck cancers (8%), and anal cancer (8%). In a study of 34,189 HIV-infected individuals and 114,260 HIV-uninfected individuals from 13 North American cohorts with follow-up between 1996 and 2007, the unadjusted anal cancer incidence rates per 100,000 person-years were 30 for HIV-infected women, 0 for HIV-uninfected women, 131 per 100,000 for HIV-infected MSM, 46 per 100,000 for other HIV-infected men, and 2 per 100,000 for HIV-uninfected men. Therefore, the incidence of anal cancer in HIV-infected MSM is now estimated to be 80 times higher than men in the general population. This increase in the incidence of anal cancer has been shown to be associated with the HIV epidemic in men.

Immunosuppression plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of anal cancer. In a large French HIV cohort study, the risk of anal cancer increased with the time during which the CD4 count was less than 200 cells/mm 3 and viral load was greater than 100,000 copies/mL. A recent analysis from the HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study, a linkage of population-based state HIV and cancer registries, showed that anal cancer is the third most common cancer occurring in excess in the HIV-positive population. Eighty-three percent of excess cases of anal cancer occurred among MSM, and 71% among those living 5 or more years since AIDS onset.

In the general population, the risk of most cancers increases with age, including cancers frequently diagnosed in HIV-infected individuals. Because effective antiretroviral treatment has greatly prolonged life expectancy, the proportion of the HIV population in older age groups has increased and will likely continue increasing in the future. Yanik and colleagues used a linkage between data from cancer registries in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute and Medicare claims (SEER–Medicare) to estimate absolute cancer risk among people age 65 years or older with an HIV diagnosis and evaluate the association between HIV and cancer in this age group. HIV was found to be associated with elevated incidence of anal cancer (adjusted hazard ratio, 34.2) among those aged 65 or older. This highlights a clear need for cancer prevention in this age group and the importance of screening.

Treatment outcomes of human immunodeficiency virus–positive anal cancers

In the general population, concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) infusion and mitomycin (or cisplatin) has been established as the standard-of-care regimen for nonmetastatic anal cancer. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy has also been shown to reduce acute toxicities compared with conventional 3-dimensional radiotherapy. For information on treatment of anal cancer in HIV-negative patients (see Rob Glynne-Jones and Sheela Rao’s article, “ Treatment of the Primary Tumor in Anal Canal Cancers ,” in this issue).

Outcomes for HIV-infected patients with anal cancer are not as well-described as for HIV-negative individuals. Patients with HIV infection had been excluded from the 3 large randomized phase III trials on anal cancer (ACT I [United Kingdom Co-ordinating Committee on Cancer Research Anal Cancer Trial], RTOG 98–11 [A Phase III Randomized Study of 5-Fluorouracil, Mitomycin, and Radiotherapy Versus 5-Fluorouracil, Cisplatin and Radiotherapy in Carcinoma of the Anal Canal], and ACCORD 03 [A phase III study to evaluate the benefit of cisplatin-fluorouracil–based induction chemotherapy and that of a higher dose of radiotherapy on cancer-free survival]) because of the uncertainties regarding toxicity, compliance, and clinical outcome. When CRT was first applied to HIV-infected patients in the pre-HAART era, reduced doses of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy were administered as a precaution against the compromised immunologic status and the presumed increased hematologic and mucosal toxicity. However, when therapy was applied in standard doses, increased toxicity, requiring treatment breaks or dose reductions, and poorer clinical outcome were reported. In 5 studies that included 53 patients, the incidence of grade 3 to 4 skin toxicity was 50% to 78%. A pretreatment CD4 count of less than 200 was identified as a factor associated with poorer anal cancer control and increased treatment morbidity in a small retrospective cohort.

In the HAART era, reports on clinical outcomes of HIV-infected patients with anal cancer have been conflicting. Immune restoration with effective suppression of HIV viral load and elevation in CD4 count could be achieved in most HIV-infected patients, with a positive impact on treatment-related side effects and compliance. Recent studies with most HIV-infected patients receiving concomitant effective HAART and CRT found no statistically significant correlation between toxicity and CD4 cell count. Blazy and colleagues reported that high-dose CRT with radiotherapy doses of 60 to 70 Gy with concurrent 5-FU and cisplatin is feasible. Some studies show that HIV-infected patients had comparable disease control and survival to HIV-negative patients, whereas others suggested that HIV-positive patients may do worse in terms of enhanced treatment-related toxicity and/or an increased risk for local relapse. There are no clear explanations for the differences, or lack of differences, in the outcomes of anal cancer in the HIV-infected versus the HIV-negative population. Almost all of these reports are limited by small patient numbers and the retrospective nature of the data. Wexler and colleagues reported the local failure rate was only 16% in their cohort, but 44% of patients had T1N0 disease, which could reflect the fact that many of the referring providers are experienced in caring for HIV-infected individuals and more likely to examine patients for HSIL and anal cancer. In contrast, one of the largest series of anal cancer patients (total = 107, HIV-infected, HIV-negative) showed that HIV-infected patients had significantly worse overall survival and colostomy free-survival compared with a similar cohort of HIV-negative patients, despite having similar treatment approach, patient adherence, and cancer stage. There were also no differences in radiation-related acute toxicity based on HIV status.

The HPV-associated E5 protein amplifies the mitogenic signals mediated by the epidermal growth factor receptor, which is broadly expressed in epithelial cancers, including squamous cell carcinoma of the anogenital tract and oropharynx. There is rationale, therefore, for therapeutically exploiting the association between HPV infection and anal cancer. Cetuximab is a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds epidermal growth factor receptor with high specificity and with greater affinity than its ligands, thus blocking ligand-induced activation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cetuximab prolongs survival when used in combination with radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, another cancer that is typically associated with HPV infection but not other head and neck cancers not associated with HPV. Cetuximab also enhances the effectiveness of cisplatin in advanced head and neck carcinoma. Based on these observations, investigators from the AIDS Malignancy Consortium and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group designed 2 trials that were concurrently conducted to determine the effectiveness of cetuximab plus CRT in patients with HIV infection (AMC045) and without HIV infection (E3205). CRT included cisplatin (75 mg/m 2 ) and 5-FU (1000 mg/m 2 /d × 5 days) × 2 cycles plus radiation therapy (45–54 Gy), plus 2 cycles of neoadjuvant cisplatin/5-FU in the first 28 patients in E3205 before a study amendment. Cetuximab (400 mg/m 2 IV, then 250 mg/m 2 IV weekly × 8 weeks) began 1 week before CRT. When the 2 trials are considered together, a noteworthy finding is that patients with HIV infection had similar clinical outcomes as those who did not have HIV infection, with about 70% being alive and recurrence free at 3 years. Treatment tolerance and the overall side effect profile were also similar in the 2 populations. These findings are consistent with population-based data indicating that, although cancer-specific mortality is increased in HIV-infected subjects compared with the general population for some cancers (eg, colorectal, pancreas, larynx, lung, melanoma, and breast cancer), this is not true for anal cancer. These findings therefore provide additional data indicating that anal cancer in HIV-infected individuals should be treated with curative intent similar to immunocompetent individuals.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are found in a variety of solid cancers and have been considered to be a manifestation of a host immune response directed against cancer cells. Virus-encoded antigens expressed in the neoplastic cells may represent neoantigens targeted by the immune system. In anal cancer, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have been demonstrated to predict overall survival and recurrence-free survival. Some have hypothesized that impaired immune response in HIV-infected patients may allow anal cancer to escape surveillance and results in poorer outcomes. Clearly, the biological basis for poor cancer outcomes in HIV-infected patients requires further study.

Management issues in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients

Because HAART allows HIV-infected cohorts to live longer, with a concomitant increased incidence of non–HIV-associated cancers, including anal cancer, concurrent treatment with HAART and anticancer therapy is increasingly common. Extrapolating from treatment studies of HIV-associated lymphomas, concomitant use of HAART and chemotherapy is tolerable in most cases and is not associated with life-threatening toxic effects, similar to those observed in patients with cancer without HIV infection. In HIV-infected patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer, most HAART regimens can be safely implemented to suppress viral replication. Typically, the preferred HAART regimens for HIV-infected patients are 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in combination with a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, a protease inhibitor (preferably boosted with ritonavir), or an integrase strand transfer inhibitor. Recent guidelines state that integrase strand transfer inhibitor–based regimens may be preferred in cancer patients receiving anticancer treatment because of their favorable drug interaction profile. Zidovudine is often avoided because it commonly causes nausea, anemia, and myelosuppression, which can be potentiated by chemotherapy. Tenofovir may lead to renal dysfunction, particularly in patients receiving other nephrotoxic drugs such as cisplatin. For protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, the potential for drug–drug interactions is high because these agents are extensively metabolized by and induce or inhibit the CYP450 system, which mediates the metabolism of more than one-half of all drugs that undergo hepatic metabolism. Protease inhibitors also may act as radiosensitizers by inhibiting proteasome function and causing apoptosis, thereby potentially increasing both tumor control and toxicity.

In HIV-infected patients with cancer, as with other HIV-infected patients, CD4 count, HIV-1 RNA level, and HAART adherence should be monitored. Because CD4 counts can be affected by malignancies or their treatment, CD4 count should be interpreted with caution as an indicator of immunologic response to HAART. For patients with anal cancer who receive pelvic radiation, myelosuppression may be severe since the major source of bone marrow is also radiated. Specifically, the CD4 + T-cell count may fall even more severely and may not readily recover to pretreatment values. In a single institution study of 60 HIV-infected patients with anal cancer, those who received CRT with effective HAART had higher pretreatment CD4 compared those who received CRT without HAART. However, median CD4 at 3 months after anal cancer diagnosis was more than 50% lower than their pretreatment value, and their median CD4 at 12 months after diagnosis was only 200 cells/mm 3 . Scatter of radiation may also affect the gut, which is also an important compartment for CD4 + T cells. Another group reported that 4 patients (11%) developed opportunistic illnesses such as candida esophagitis during long-term follow-up of their anal cancer. Therefore, antibiotic prophylaxis should be implemented to further reduce infectious complications during the treatment of HIV/AIDS-associated anal cancers based on careful assessment of risk.

The guidelines for prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in patients with HIV take into account risk and history of exposure, as well as the status of the immune system, particularly as reflected by the CD4 count, the receipt of and duration of HAART, and the response to HAART. The guidelines for preventing of infections in patients with cancer are centered on the degree and duration of neutropenia, a key risk factor for infection. CRT also potentiates the neutropenia associated with HIV/AIDS. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors can reduce the effects of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, and is often liberally used by oncologists when treating cancer in HIV-infected patients. The caveat is that granulocyte colony-stimulating factors should not be given concurrently with CRT owing to concern for worsening hematologic toxicity. The immunologic deterioration following CRT may have an impact on the clinical course of the HIV disease and may be associated with an increased risk of opportunistic infections and diseases. Both the HIV-related and cancer-related guidelines need to be considered to prevent opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients with anal cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree