Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infections and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Lisa K. Simons

Marvin E. Belzer

KEY WORDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

Antiretroviral therapy (ART)

Exposure

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Prevention

Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

Testing

Transmission

Treatment

Virus

As of December 2012, over 35 million people worldwide were living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus responsible for the advanced immunocompromised condition known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The number of people living with HIV continues to rise with the combined effects of improving therapies and high rates of new infections, particularly among adolescents and young adults (AYAs). While antiretroviral therapy (ART) allows most adherent youth to live healthy lives with simple once-a-day regimens, existing challenges for care providers involve identifying HIV-positive youth, engaging them in care, and assisting them with long-term adherence to medications.

In July 2013, 3 years after the establishment of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, the nation’s first comprehensive federal plan addressing the domestic epidemic, President Barack Obama released an Executive Order instituting the HIV Care Continuum Initiative.1 Also referred to as the HIV treatment cascade, the “HIV care continuum” provides a framework for understanding engagement in care as a spectrum, ranging from “not in care” (either aware or unaware of HIV status) to “fully engaged in HIV primary care.” For individuals to fully benefit from treatment, they need to be aware of their infection, engage and remain in medical care, and obtain and adhere to ART. Accordingly, HIV service delivery in the US has shifted toward a public health model with strategies simultaneously aimed at improving testing and early diagnosis, enhancing linkage and retention in care, and supporting access and adherence to ART.

The causative agent of AIDS is HIV, a single-stranded RNA retrovirus that infects and leads to the destruction of CD4+ T lymphocytes. HIV-1 is the cause of most cases of AIDS in the world. HIV-2, a retrovirus related to HIV-1, is found primarily in Central Africa and generally has a slower progression (20 years versus 5 to 10 years with HIV-1) but a similar spectrum of disease.

Acute HIV infection presents as a mononucleosis-like illness in many but not all patients, 2 to 6 weeks after infection. The illness typically lasts 1 to 2 weeks and causes nonspecific constitutional symptoms as well as myalgias, lymphadenopathy, and sore throat (Table 31.1). Without a high index of suspicion, the diagnosis may be unrecognized by clinicians.

TABLE 31.1 Clinical Manifestations of Acute HIV-1 Infection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

While the phase of illness following acute infection is one of clinical latency, it is now clear that viral production is steady at an estimated 10 billion virions daily. During this time, T cell production and destruction remain precariously balanced.

A slow but steady depletion of CD4+ T cells occurs in all but a small percentage of untreated patients, who are referred to as long-term nonprogressors. Without treatment, the average rate of decline of CD4+ T cells is about 50/mm3/year and most patients develop AIDS (severe immune deficiency) over a period of 8 to 10 years. Approximately 10% of newly infected individuals will rapidly progress to an AIDS diagnosis within 4 years. Numerous studies indicate that ART can suppress the viral load to undetectable levels in most patients. Viral suppression is associated with a steady immune reconstitution in most patients. Even patients with severe depletion of their immune systems can often return to excellent health after successful treatment.

AYAs identified with HIV early, who successfully initiate ART, should have a near-normal life span if good adherence persists and risks, such as drug use, are avoided.2 There is growing evidence that chronic HIV infection elicits systemic inflammation that accelerates risk for cardiovascular illness. Even with effective antiretroviral treatment, HIV-positive individuals have higher cardiovascular risk, and cardiovascular disease has emerged as an important cause of death in patients with HIV.3 Research is in progress to determine if therapy with medications like statins can reduce inflammation and cardiovascular risk.4

Another area of emerging research is neurocognitive function in HIV-positive adolescents. In one study of 220 recently diagnosed youth (mean age 21) naive to ART, 67% of participants demonstrated neuropsychological testing consistent with asymptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder.5 There were high rates of impairment in learning and memory as well as executive functioning that clearly impact clinicians’ approach to patient management. Research examining the impact of ART on neurocognitive changes is ongoing.

Prevalence

At the end of 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 1,148,200 persons aged 13 and older were living with HIV infection in the US, including 207,600 (18.1%) persons unaware of their infection. Youth aged 13 to 24 made up 7% of the 1.1 million living with HIV.6

Incidence

From 2008 through 2011, the number of new HIV infections in the US remained stable, at approximately 50,000 new cases each year. In 2010, one in four new infections occurred in AYAs aged 13 to 24.6

Age

AYAs are particularly impacted by HIV. In 2010, the CDC reported an estimated 12,000 new HIV infections in youth aged 13 to 24. Although young people in this age group represented 16% of the US population in 2010, they accounted for 26% of all new diagnoses made that year. Young adults aged 20 to 24 have the highest number of new cases of HIV compared with other age groups. The CDC estimates that approximately 60% of all youth living with HIV in the US are unaware of their infection.6

Ethnicity

Communities of color continue to be disproportionately impacted by HIV infection. Among youth in the US aged 13 to 24, 60% of new infections occurred in Blacks and 20% in Hispanic in 2010.6

Gender

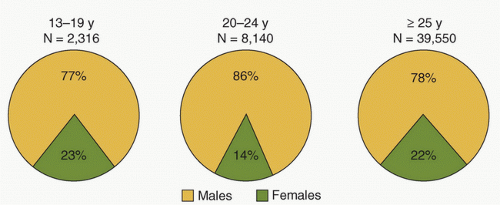

At the end of 2010, 75% of adolescents and adults aged 13 years or over living with HIV were men and 25% were women. Figure 31.1 shows that the number of young males living with HIV is higher than females, and this difference increases with age. It is important to note that while transgender individuals are at highest risk for HIV, data for these communities are lacking as a result of the absence of uniform data collection approaches.

Transmission

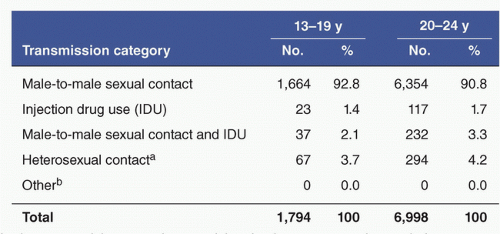

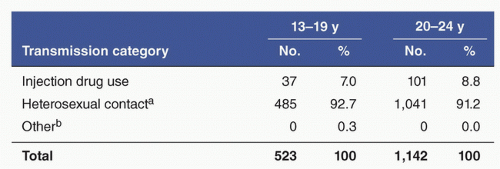

Figures 31.2 and 31.3 show the common routes of transmission for males and females diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in 2011. Most new cases in males occur in men who have sex with men (MSM), while the majority of new infections among females are transmitted through heterosexual contact and intravenous (IV) drug use.6 Young men who have sex with men (YMSM), especially Black and Hispanic YMSM, are at especially high risk of acquiring HIV.

HIV can be transmitted only by the exchange of body fluids. Blood, semen, vaginal secretions, and breast milk are the only fluids documented to be associated with HIV infection. Although HIV is found in saliva, tears, urine, and sweat, no case has been documented that implicates these fluids as agents of infection.

IV Drug Use

HIV is easily transmitted by needle sharing. Because of the unreliability and frequent unacceptance of needle bleaching and unacceptance or inaccessibility of drug treatment, almost all public health organizations support needle exchange programs. In these programs, injection drug users can exchange dirty needles for clean ones while at the same time gaining access to condoms, bleach, and referral resources. Many programs across the US have shown that injection drug use does not increase in the community or in an individual user when needle exchange is available. Moreover, HIV and other blood-borne disease transmissions (e.g., hepatitis) are markedly reduced with the availability of needle exchange programs.7

Sex

Sexual transmission of HIV is thought to have a hierarchy of relative risk. Receptive anal intercourse without condoms is riskiest, followed by insertive anal intercourse and vaginal intercourse. Oral sex is categorized as less risky but has been shown to transmit HIV. Studies have shown that the proper and consistent use of latex condoms or dental dams can markedly reduce the risk for HIV transmission during sex.8

Vertical Transmission

Universal opt-out HIV screening of pregnant women, antiretroviral treatment and prophylaxis, use of cesarean delivery when appropriate, and avoidance of breast-feeding have greatly reduced perinatal HIV transmission in the US. With early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and avoidance of breast-feeding, transmission risk is reduced to 2% or less.9 According to the CDC, in 2011, an estimated 192 children younger than 13 years were infected with HIV, 127 of these being perinatally infected.6

The HIV prevention paradigm has shifted significantly in recent years. Primary prevention efforts to reduce the HIV risks of uninfected persons have expanded beyond behavioral interventions to include biomedical interventions like preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), public health strategies like HIV counseling and testing, and structural interventions that address community partnerships and collaboration, including increasing access to condoms. The White House and other public health leaders have increasingly emphasized secondary prevention (reducing transmission risks from persons living with HIV) through “Treatment as Prevention.”

Primary Prevention

Preexposure Prophylaxis

PrEP is an HIV prevention method that uses a daily antiretroviral pill to reduce transmission to HIV-negative individuals at high risk of infection. In a multinational study of 2,470 sero-negative MSM and 29 transgender women, participants were randomly assigned to emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada®), a two-drug combination antiretroviral pill, or a placebo. All received HIV testing, condoms, and risk reduction counseling. PrEP was found to reduce the risk of transmission by 44% among all participants and by 92% in those with detectable drug levels. No differences were detected in high-risk sexual practices or sexually transmitted infections (STIs) between the two groups.10 Two large trials conducted in Africa, Partners-PrEP and TDF2, demonstrated the efficacy of PrEP with antiretrovirals in heterosexual individuals at high risk of HIV acquisition.11,12 Based on these results, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of daily emtricitabine/tenofovir in 2012 for uninfected adults (including adolescents aged 18 and older) at high risk of acquiring HIV, to be used in combination with safe sex practices. Recommendations include the integration of behavioral interventions with ongoing HIV testing for those choosing to utilize PrEP.

While initial studies suggest that PrEP may be a promising strategy for HIV prevention, research studies focusing specifically on adolescents are needed prior to development of recommendations for the use of PrEP in adolescents under 18 years. Questions remain as to whether the use of PrEP in youth is cost effective, whether youth engaging in high-risk behaviors can adhere to daily use of PrEP, and whether or not high-risk youth will continue to use condoms at the same rate as they did prior to the introduction of PrEP. Current studies are examining the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of PrEP in adolescents (under 18 years). Research is also investigating whether topical PrEP or intermittent use of oral PrEP is effective.

Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis

Nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) after injection drug use, sexual, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV may be recommended to prevent HIV infection for persons seeking care within 72 hours of exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids. Expert consultation is available through the National HIV/AIDS Clinician’s Consultation PEPline at 1-888-448-4911 (see Additional Resources at the end of this chapter) to help clinicians determine if the exposure represents substantial risk and which antiretroviral regimen is most appropriate. Sexual assault survivors should always be offered nPEP. When PEP is recommended, it should be initiated as early as possible after exposure (ideally within 72 hours). nPEP typically consists of a 28-day two- or three-drug antiretroviral regimen. Sequential follow-up HIV testing should be organized by the clinician. It is unknown if treatment for exposures initiated after 72 hours provides any reduction in HIV infection risk.

HIV Prevention Education

AYAs frequently receive general HIV education in school settings. More targeted approaches with high-risk populations like YMSM, transgender women, or women of color are best employed utilizing evidence-based interventions that are strongly connected to HIV and STI screening, such as those published by the CDC (http://www.effectiveinterventions.org/en/HighImpactPrevention/Interventions.aspx). The CDC has also increased focus on community-level structural changes involving changing policy, laws, access to services, and so on.

Appropriate educational interventional goals for HIV-negative AYAs include the following:

Reducing misinformation about and prejudice against HIV-positive persons

Helping to reduce high-risk behavior, including recommendations to decrease unprotected sexual activity, numbers of sexual partners, and experimentation with drugs

Supporting AYAs who choose abstinence

Increasing use of condoms and other barrier methods by AYAs who are sexually active

Encouraging young people in sexual relationships to get HIV tested along with their partners

Referral and/or linkage to behavioral and biomedical interventions (e.g., nPEP and PrEP) as appropriate.

HIV/AIDS prevention education should be conducted at schools, religious organizations, youth organizations, medical facilities, and meetings with parents. Media (Internet, television, radio, magazines) are powerful methods to impart information that may change AYAs’ attitudes. Outreach to youth where they congregate can be an especially effective method of reaching high-risk populations such as homeless, gang involved, or out-of-school youth. Involving peers in the education process can also be helpful.

It is important to offer HIV/AIDS education in a language and format that the adolescent or young adult can understand. The information must be simple, accurate, and direct. Previously, the federal government allocated many resources to abstinence-only prevention education, despite a lack of evidence that this approach was effective. Abstinence-based education, which promotes abstinence but also provides information on how to reduce risk if sexually active, has been shown to delay the onset of sexual activity in some studies. Information on peer-reviewed programs that have been shown to be effective can be found at http://www.effectiveinterventions.org/en/Home.aspx.

Secondary Prevention

Since the onset of the HIV epidemic, prevention strategies in the US have largely targeted persons at risk for acquiring HIV and have been aimed at reducing sexual and drug-using risk behaviors. While these continue, new efforts have been initiated that place a greater emphasis on targeting HIV transmission by those living with HIV. These efforts include peer navigation programs (where AYAs diagnosed with HIV are supported by peers who are living with HIV or have experience with HIV), medication adherence interventions, and behavioral interventions that focus on reducing STIs. Data indicate that less than half of youth infected with HIV are aware of their status and of those in care, less than half have adequately suppressed their HIV.

The most significant change in the landscape for HIV prevention is the emphasis on the role of HIV treatment as a method of HIV prevention, a shift resulting from mounting evidence suggesting that treating HIV-positive individuals reduces HIV transmission to uninfected partners. In 2011, a landmark study conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN 052) was stopped three years earlier than planned when it became clear that treating HIV-positive individuals with ART regardless of their T cell count significantly reduced the risk of heterosexual transmission and that it would be unethical to continue recruiting for the study. The randomized study showed that by suppressing detectable viremia, ART produced a 96% reduction risk in sexual transmission of HIV to uninfected partners.13 “Treatment as prevention,” which refers to the personal and public health benefits of treating HIV-positive individuals with ART, has driven treatment guidelines to recommend that HIV-positive individuals consider taking antiretroviral medications as soon as they are prepared to be adherent.

Early diagnosis and entry into care are critical steps in addressing the HIV epidemic, yet many HIV-positive individuals, especially youth, remain unaware of their status. The importance of HIV testing cannot be overstated. A number of factors, including consent, confidentiality, and appropriate counseling, should be considered when screening for HIV in AYAs.

Consent and Confidentiality

Health care practitioners must balance the protection of AYAs’ rights against the amount of information needed to deliver proper care. Laws governing an individual’s ability to consent for HIV testing and receive confidential care vary within the US and from country to country. Current US regulations are described here:

Individuals older than 18 years who are competent: The CDC recommends that patients in all health care settings receive HIV testing as part of routine primary medical care. Separate informed consent (from the general medical consent) need not be done and prevention counseling should not be required for HIV diagnostic testing or as part of HIV screening programs.

Individuals between 12 and 17 years: The laws vary widely from state to state. According to the Guttmacher Institute, all 50 states and the District of Columbia allow minors to consent to STI services, although some states specify a minimum age (generally 12 or 14 but 16 in South Carolina) one must reach before they can provide consent.14 Thirty-one states explicitly include HIV testing and treatment as part of STI services for which minors can consent.14 Many states allow (but do not require) physicians to notify a minor’s parents that their child is seeking STI services.

Individuals younger than 12 years and incompetent adolescents: For these individuals, a third party (parent or guardian) authorizes testing. However, this authorization may be restricted by state laws.

An increasing number of states have statutes governing HIV testing. Without such a statute, general laws regarding minors apply. It is not clear whether HIV testing would fall under the category of consent for STI services in states that do not declare HIV to be an STI. Clinicians worldwide need to be familiar with local laws regarding the following:

Consent for testing: Who can consent? What is the required informed consent? Are pretest and posttest counseling available?

Who can receive the results of these tests and under what circumstances?

Where can test results be recorded?

What can be written in the chart regarding testing and test results?

To Whom Should HIV Testing Be Offered?

In 2006, the CDC modified its recommendations to advise that HIV testing be routine for all sexually active adolescents and adults between the ages of 13 and 64 years when they access health care. Youth should be advised that they will be tested and given the option to decline. Following initial testing, persons at high risk should be screened at minimum once annually. Prevention counseling is not required but does continue to offer benefit for health care systems that have the ability to provide this service. At the time of this publication, laws in all but two states (Nebraska and New York) were consistent with these CDC recommendations.15 Clinicians in the US can access more information regarding state-specific laws at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/index.html. Clinicians practicing outside of the US should be familiar with local laws governing HIV testing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree