Hospice

Martha L. Twaddle

Sally A. Kelley

END-OF-LIFE CARE

For each of us, the sounds of our time passing are amplified in our feelings and emotions, in our fears and anxieties, in our loves and our guilts, in our thoughts, beliefs, and hopes. It is to these that we must listen if we are to hear the sounds of time passing and if we are to capture the meaning of those sounds. However, we can neither listen for and to, nor can we really hear, the sounds of our time and others’ time passing if we are fragmented, scattered, and drawn here and there under the force of untold stresses, through one distraction after another. David Roy (1)

National data reports tell us that over 80% of those who die in the United States do so after a lengthy, progressively debilitating illness (2). In essence, over 80% of the time, the outcome of the disease is predictable, but it is likely that the timing of the outcome is not. In the oncology model, the trajectory of the illness has changed over the recent decades to increasingly be one of a chronic progressively debilitating illness, punctuated by acute exacerbations with temporary recoveries. Like nonmalignant illness, oncology patients may likely experience more frequent exacerbations in their final months and years, these crises coming closer and closer together with less and less time or capacity for an interval sustained recovery. These frequent exacerbations may be related directly to the malignant illness or are oft times caused by associated morbidities or infections. This pattern of closely occurring crises focuses the healthcare teams on “rescue” behaviors and may obscure their perspective as to the overall pattern of decline. Unlike nonmalignant illnesses, more has been clarified as to the pattern of faradvanced malignant diseases, characteristically punctuated by a precipitous decline in functional status, with the trajectory toward death more typically predictable, or at the least, recognizable (3,4).

PATIENT AND FAMILY GOALS MAY LACK SYNERGY WITH MODERN HEALTH CARE

The data also tell us that when faced with approaching death, modern Americans prefer to maximize the time with those activities that are meaningful to them and speak to the integrity of their individual well-being (5,6,7,8,9). Unfortunately, with encroaching illness, the time spent in organizing resources, navigating the complexity of healthcare systems, and receiving institutional-based “care” through procedures, tests, and products tends to overwhelm the energies of individuals and families. When given the choice, most patients likely would not elect to focus their last days and energies on interactions with healthcare systems. But the operative phrase within that statement is “when given the choice.” Informed consent regarding procedures is the standard of care in health care; however, advance care planning discussions that might provide opportunity for patients and families to modify or decline further disease-focused interventions without the risk of abandonment, real or perceived, are not yet routine practice in all settings of care (10,11,12,13).

In the disease management model, resources are focused on the eradication of the disease and prolongation of life. The goals and resources of care are focused on disease intervention. The physician, nurse, and others work in the warrior roles of fighting disease and within this context, see death as failure, and the lack of disease-interventional treatments as “doing nothing.” It is normative for a physician who has exhausted all protocols in fighting a malignancy to say “I have nothing left to offer you” when in fact, an armamentarium of supportive care modalities may be available and of benefit. The warriors of health care do not typically have the perspective to ask the questions that would thereby generate the choices. This may not be for any lack of empathy on their part but rather attests to the emphasis of their training and practice, the finely honed intervention skills that are prioritized within the highly technologic, science-based environment of healthcare centers.

PALLIATIVE CARE COMPLEMENTS TREATMENTS

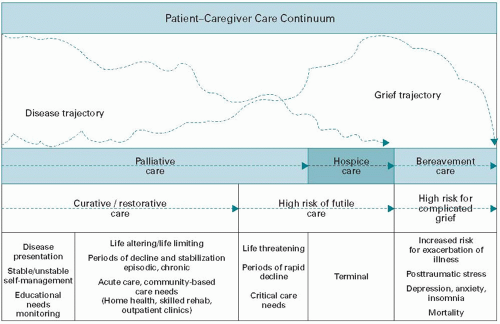

Palliative care by definition and practice is not an alternative, per se, to this approach, but rather represents the foundation of good medical care (14). This approach views the patient as a whole person in the context of his or her family and his or her community and seeks to understand the cultural, social, spiritual, and psychological aspects that will influence the provision or acceptance of professional medical care. The emphasis of palliative care is to clarify the goals of care in the light of how the individual defines the quality and meaning of his or her life. With the goals defined and documented, care ideally moves from crisis intervention to crisis avoidance, resources for support and advocacy are defined earlier in the illness, and discussions of the burden and benefit of interventions are recurrently pursued. Palliative care is thereby a continuum of supportive care

that ideally begins at the time of a potentially life-limiting diagnosis and actively supports the patient and family throughout the course of illness, however long that journey may be (Fig. 46.1) (15,16,17).

that ideally begins at the time of a potentially life-limiting diagnosis and actively supports the patient and family throughout the course of illness, however long that journey may be (Fig. 46.1) (15,16,17).

HOSPICE CULMINATES THE CONTINUUM

Within this continuum of palliative care, and most often at its end, is hospice, which is best defined as the most intensive, refined form of palliative care. Hospice is a philosophy of care that recognizes that the disease is not curable, that time is limited to months at best, and that symptom control and quality of life are preeminent goals. In this paradigm, all interventions and therapies must have immediate, tangible benefit to the patient and family, consistent with their personally defined goals. Hospice views death as an expected outcome within a discrete time frame. It offers a support system to patients, families, and professionals that affirms the outcome of death not as failure, but its heralded approach as opportunity to maximize quality so that the patient might live well until death. Recognizing the time limitations of life allows patients and families to prioritize the activities and interactions that have meaning, to seek closure personally and practically, and to have an opportunity to “leave a legacy,” if so desired, or to have some focused intent as to how or even in what manner one will be remembered after death.

ROOTS OF HOSPICE CARE

Hospice is a term with deep history. Originally, places of safety for travelers on pilgrimage throughout the ancient Middle East (c. AD 400), these centers of “hospitality” evolved into the earlier hospitals of Europe, oft times operated and staffed by religious orders. Dame Cicely Saunders of Great Britain is credited with launching the modern concept of hospice care (Fig. 46.2) (18). Dame Saunders initially practiced as a nurse during World War II, but a back injury forced her to redirect her career to medical social work. In this context, she cared for and befriended a young man, David Tasma, a 40-year-old dying of inoperable cancer. Visiting him frequently in hospital, she witnessed how his symptoms were controlled by the administration of morphine and noted particularly how, when free of pain, he “had time to sort out who he was, dying at the age of 40, and coming from the Warsaw ghetto. Of course, leaving nobody behind and feeling he had made no impression on the world for ever having lived in it. But as we were talking, he said he would leave me something in his will, he had insurance, and he said, ‘I’ll be a window in your home.’ And the idea of openness to everybody who might come, openness to every future challenge, really stems from that gift, which was, I think, the founding gift of the whole hospice movement, made by David Tasma, who thought his name would never mean anything to anybody” (19).

THE EXPANSION OF THE BRITISH MODEL OF HOSPICE

The original concept of hospice in England, sparked into being by Dame Saunders and David Tasma’s gift, was care for those with advanced cancer provided in an institutional setting, in essence, a specialty hospital. St. Christopher’s hospice opened in 1967 and in this setting, Dame Saunders pioneered the application of the scientific approach to the care of the dying, establishing many of the current best practices of palliative medicine, in particular, the around-the-clock administration of analgesic therapy to control pain symptoms. Dame Saunder’s trainees further developed hospice in the world.

Dr. Robert Twycross established the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Hospice/Palliative Care at the Sir Michael Sobell House in Oxford. A prolific writer and erudite teacher, he has written and published extensively on pharmacologic interventions in pain and symptom management.

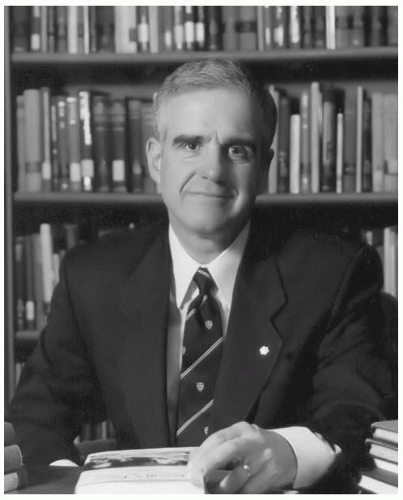

Dr. Balfour Mount (Fig. 46.3), a urologic surgeon at McGill University, is credited with having coined the term “palliative medicine” to describe the medical discipline of hospice care. His work at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal helped moved forward the integration of this care model throughout North American and, along with Dr. Josephina Magno, contributed substantially to the formation in 1988 of the Academy of Hospice Physicians which later evolved to the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) (20).

Florence Wald, PhD, Dean of the Graduate School of Nursing at Yale University, opened the New Haven Connecticut Hospice in 1974. This was a sentinel event for hospice, the introduction of the hospice care model into the United States; and the form of hospice care being delivered in the home setting, a model that is most common within the United States to this day. Early models of inpatient hospice care were established at Calvary Hospital and St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital in New York City; however, the model that has grown prolifically in the United States has been home care (21).

GROWTH WITHIN THE UNITED STATES

The growth of hospice in the United States found fertile soil in the work of Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, who raised the awareness of death and the recognition of the patient’s coping mechanisms through her observational studies published in Death and Dying in 1969 (22). In keeping with the grassroots psychology of the American, hospice programs were established at the community level, often by professional

volunteers, to provide an alternative to institutional-based dying. The early pioneers of hospice in the United States were vocal in their condemnation of “modern” health care’s inattention to the needs of dying patients and their families and sought to establish healthcare systems that existed outside of the mainstream in reaction to this deficit. Within the United States, terminally ill patients with diagnoses other than cancer were increasingly served by hospice programs: by 2009, nearly 60% of patients were admitted with noncancer diagnoses, with the most common being end-stage heart disease (23). The New Haven program brought together hospice leaders and advocates in the late 1970s to establish guidelines for the operations of hospice programs in the United States. This led to the development of the National Hospice Organization, now the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO). The mission of this membership organization that represents the nation’s hospice programs is “to lead and mobilize social change for improved care at the end of life” (24).

volunteers, to provide an alternative to institutional-based dying. The early pioneers of hospice in the United States were vocal in their condemnation of “modern” health care’s inattention to the needs of dying patients and their families and sought to establish healthcare systems that existed outside of the mainstream in reaction to this deficit. Within the United States, terminally ill patients with diagnoses other than cancer were increasingly served by hospice programs: by 2009, nearly 60% of patients were admitted with noncancer diagnoses, with the most common being end-stage heart disease (23). The New Haven program brought together hospice leaders and advocates in the late 1970s to establish guidelines for the operations of hospice programs in the United States. This led to the development of the National Hospice Organization, now the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO). The mission of this membership organization that represents the nation’s hospice programs is “to lead and mobilize social change for improved care at the end of life” (24).

Figure 46.3. Dr. Balfour Mount is credited for having coined the term “palliative medicine” to describe the medical discipline of hospice care. |

Through the involvement and advocacy of such leaders, the United States Congress authorized the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB) in 1982. This entitlement benefit addresses the types of services provided within hospice care, the persons eligible to elect the benefit, and the payment system that supports the care. Hospice programs throughout the United States moved to become Medicare certified by adhering to these federal regulations. Medicaid and commercial insurance developed similar guidelines, and hospice programs thereby could bill and receive insurance dollars to support care. The Hospice Medicare benefit is divided into periods, the initial being two 90-day periods with an unlimited number of 60-day increments to follow. Each benefit period requires physician recertification around prognosis and goals of care (25,26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree