Home Care and Caregivers

Betty R. Ferrell

Barbara J. Whitlatch

Intensive Care of Home Care

Since the mid-1980s, there has been a major shift in home health care. In the United States this shift was caused originally by the prospective system; it has been sustained by current trends toward managed care. Long hospital stays have been replaced by early discharges and the shifting of the burden of care to the home. The intensity of care for these home care patients has also changed because of the demographics of both patients and caregivers. Home care nurses and family caregivers have been charged with managing patients with complex and highly technical treatment plans. Home care is characterized by intensive management of symptoms and the need for supportive care of both the patient and the family caregivers who assume the burdens of cancer and its treatment (1, 2, 3).

Complexities of Home Care

Until recently the study of symptom management has been largely confined to major symptoms, such as cancer pain, and acute care settings. Recent studies have focused on the special needs of patients in other settings, including the nursing home (4, 5, the hospice (6, 7, and the home (8, 9). Several factors can influence palliative care in these settings. Heavy reliance on family members, access to diagnostic facilities, and, often, limited pharmacy services can influence the effectiveness of pain and symptom management at home.

It may be assumed that comfort is enhanced in home care, as the home environment has been considered preferable to institutional settings. Indeed, patients, families, and health care professionals often elect care at home because they assume that patients are more comfortable there. Research has not confirmed this perspective and has demonstrated that treatment may not be substantially better at home (10, 11, 12). As researchers have extended studies into the home care setting, barriers have been described that actually hinder pain management in the home, including patient’s and family’s fears of addiction, failure of the patient to report pain, and limited access to needed services. These facts emphasize that fulfilling the patient’s preference to be at home may not necessarily result in effective symptom management.

Symptom management at home is different from that at the hospital or other institutional setting. Hospitals typically provide technical equipment and services for acutely ill patients. For patients with complex problems, inpatient care often includes a variety of aggressive or invasive strategies for diagnosis and definitive treatment of the underlying conditions. Home care, by contrast, relies heavily on low-tech strategies, concentrating mostly on symptom management. The overall effectiveness of these different strategies at home in comparison with hospitals remains difficult to analyze.

Cancer as a Family Experience

Cancer and other life-threatening illnesses, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), are generally recognized as affecting the entire family unit rather than a single individual. The recent shift in health care, with movement toward home care as the predominant setting, emphasizes the importance of family involvement in the total care needs of the patient. It is indeed remarkable that care which only a decade ago was reserved for intensive care units (ICUs) by specially trained registered nurses is now delegated to family caregivers in the home environment who have had little or no preparation to assume both the physical and emotional demands of illness. Home care has advanced from low-tech care, focused on follow-up for patients discharged from hospitals, into its current status as the setting for active treatments, including chemotherapy, intravenous fluid administration, blood transfusion, complex wound care, and many other technical procedures. Recent literature has acknowledged the intense demands of family caregiving at home largely in the areas of technical care, acquisition of skills, and provision of intense, 24-hour physical caregiving. Less emphasis has been placed on the emotional burdens of assuming responsibilities for the patient’s well-being or peaceful death in the home. A study involving 28,777 patients with cancer published in 2004 revealed that care is in fact becoming more aggressive over time with increased use of chemotherapy, increased ICU stays and later referral to hospice (13).

The home environment can be viewed as a delicate balance. At one end of the spectrum are the many demands that the home care environment offers that, if out of balance, can result in intense burdens for family caregivers and compromised care for patients. At the other end are the many benefits of home care. The home care environment can potentially offer the patient improved physical comfort, the psychological comfort of familiar surroundings, an opportunity for healing of relationships, and the ability for patients and families to benefit from the compassion of giving and receiving comfort care and a shared transition from life to death (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

Another significant trend has been the use of home as the setting of care. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, health care professionals generally made the decision whether to discharge

a patient to the home or to offer an extended stay in an inpatient setting based on patient or family preferences. The decade of the 1990s transformed home care as the primary setting of active treatment as well as palliative care. Very important, however, has been the diminished choice on the part of patients and families primarily due to changes in the health care system. Although some patients and families have volitionally chosen home care, others have had care relegated to the home setting due to health care system or hospital determinants.

a patient to the home or to offer an extended stay in an inpatient setting based on patient or family preferences. The decade of the 1990s transformed home care as the primary setting of active treatment as well as palliative care. Very important, however, has been the diminished choice on the part of patients and families primarily due to changes in the health care system. Although some patients and families have volitionally chosen home care, others have had care relegated to the home setting due to health care system or hospital determinants.

The outcomes of home care may often be best evaluated by the effects on family caregivers following the death of the patient and during bereavement. Hospice providers have long recognized that positive experiences with caregiving in the home result in positive bereavement and adaptation by family members after the patient’s death. Feelings of inadequacy in providing home care, patient complications, and deaths that are less optimal than anticipated can result not only in the patient’s diminished quality of life or quality of death, but also in long-term consequences for the family. Home care then is best viewed as not merely care provided to a single individual in the home environment but rather as a family experience in which every aspect of care provided to the patient or the provision of care by the family caregiver will impact the others (20, 21, 22, 23).

Public Denial of Death and Influence on Care

Much literature has addressed the social need to deny death and the reluctance of individuals in society to accept death and dying amidst a health care system focused on cure. Efforts by the hospice movement, the social influences of AIDS, the prevalence of cancer, and other factors have in many ways made our society confront the reality of death in recent years. In an effort to diminish societal denial of death and heighten awareness of the growing end-of-life movement, the well-known documentary reporter Bill Moyers produced a four-part series for public television that aired in fall 2000. Through his years of work in preparing “On Our Own Terms: Dying in America,” Moyers sought to address myriad aspects of how individuals, families, and the health care systems view and manage death in the United States. This was the first time in modern US history that such a well-known media personality devoted such substantial effort to examining the societal views toward the end of life. For professionals in the end-of-life movement, this represented a major coup in overcoming societal silence, denial, and aversion to such a critical stage in life.

In the 1990s, several other programs were developed in the United States to address the need for increased research, professional education, and advocacy in end-of-life care, including aspects of home care, hospice, and community involvement. The Project on Death in America was established by the Open Society Institute through a grant from the Soros Foundation, one of the wealthiest philanthropic foundations in the United States. Interestingly enough, the benefactor recognized the incredible dearth of resources and training in caring for those at the end of life. The Project on Death in America programs addressed aspects of end-of-life care in various professional fields, including medicine, nursing, social work, chaplaincy, and other social service fields.

These efforts at examining the end of life as a natural life stage have been balanced by intense media attention on new potentially curative therapies, such as gene therapy, biomedical engineering, and advanced technologies. This attention encourages continuation of the death-denying society. Health care providers should recognize that for many family caregivers and patients, the death that they are now witnessing is perhaps their first personal encounter with the termination of life. Family caregivers struggle with the sanctity of life and denial of death just as do health care professionals and society at large. However, the profound experience of dying, or of caring for a loved one who is dying, transcends all aspects of home care. This experience has been described as an all-encompassing aspect of the clinical care of the terminally ill patient at home (24).

Physical and Psychosocial Issues

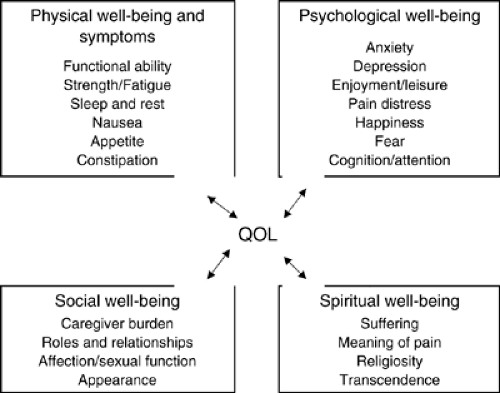

The needs of patients and family caregivers in home care span the domains of quality of life, as depicted in Figure 56.1. Home care needs most often involve physical needs, such as management of pain and other symptoms, and treatment of the side effects associated with treatment of the disease. Nutritional needs, sleep disturbance, fatigue, incontinence, and other physical aspects of disease and treatment are common priorities of home care. In fact the area of physical well-being and symptom management has been the focus of home care and is also the area with the greatest scientific basis for the practice of care in the home (25, 26).

Psychological well-being is predicated on pharmacologic management of symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, as well as counseling to address issues such as fears, loss of control, and the many other psychological demands of life-threatening illness. Similar to psychological needs are the patient’s social needs, such as the ability to maintain appearance and normal roles and relationships, and family issues such as financial concerns. The ability to meet psychological and social needs is more difficult outside palliative care programs, in which there is limited access to social workers, clinical psychologists, and other support personnel (27, 28, 29).

Spiritual well-being presents perhaps the greatest challenge in home care. In the institutional setting, such as the inpatient hospital, chaplaincy services may be more available. Yet it is during the advanced stages of illness, when care takes place in the home, that spiritual needs, like psychosocial needs, may become more prominent. This issue emphasizes the importance of psychosocial and spiritual assessment to determine unmet needs (30, 31).

Challenges to Symptom Management at Home

There are at present many uncertainties about the future of the health care system in the United States and in virtually all countries. A certainty, however, is that care continues to shift into the outpatient and home care environment. Therefore it is patients and families who will assume most of the care in the future. One of the greatest challenges in this area derives from demographical and social influences such as the impact of a steadily aging population of patients with multiple chronic illnesses. Care of the patient with cancer at home becomes far more difficult when the patient is 80 years old and also has concomitant illnesses such as cardiac disease, hypertension, and diabetes, with their associated medications and treatments (32, 33). There is still limited attention focused on the special care needs of the geriatric population at home and that of their caregivers, who are often elderly children. Expanded efforts in attending to complex needs of the aging will need to be adopted, especially given the growing percentage of population over the age of 65 (34).

An equal challenge rests in the demographics of family caregivers in the home. Research has revealed that approximately 70% of caregiving is provided by elderly spouses in the home and an additional 20% is provided by daughters or daughters-in-law, who are often balancing full-time employment as well as the demands of their own families while providing intensive care to their loved ones.

One of the most challenging aspects of home care will be the future impact of managed care and similar factors influencing the types and extent of care to be provided in the home. Factors, such as limitations in the types of services available, the frequencies of visits, and the duration for which this care can continue, will make home care extremely challenging. In essence, as the intensity of needs is increasing, the available resources in home care are diminishing.

Involvement of Family Caregivers in Medications

A primary task of home care related to cancer and other terminal illness is management of medications. It is enlightening to realize that home care nurses and other professionals assume similar responsibilities in other settings only after formal courses in pharmacology and with support available from colleagues, pharmacists, and physicians reached by direct access. This is particularly true in oncology, where symptom management is often either accomplished on an as-needed basis for symptoms, such as nausea or anxiety, or with necessary titration of around-the-clock dosing of medication such as analgesics.

Management of medications is important not only to preserve the patient’s comfort but also to diminish the burden on the family and avoid costly complications such as repeat hospitalizations when medications are not effectively used. Patients and family caregivers often do not have the necessary knowledge to judge indications for administration of medications or the delicate issues involved with titration or the side effects of medications. Health care providers can make a valuable contribution to the care of patients at home by insuring that medication schedules are made as simple as possible using single agents rather than multiple drugs, and maintaining the simplest possible routes of administration and dosage schedules. Patients require assistance with important decisions regarding the use and titration of medications and practical techniques such as written dosage schedules, use of self-care logs, and provision of guidelines to help in medication choices.

An additional burden of family caregiving, often neglected, is the costs assumed by patients and family caregivers themselves related to pain management and home care (35). Families incur significant expenses related to home care in advanced disease, much of which is not reimbursed. Costs include direct expenses, such as medications, as well as extensive indirect costs such as loss of wages. Most of the cost savings to third-party payors have resulted in increased costs assumed by patients and families.

Cultural Considerations of Home Care

The increase in multiculturalism in the United States has added another dimension to the complexity of health care provision as well as coverage. Language barriers, cultural traditions, and religious beliefs create the need for increased sensitivity and knowledge on the part of health care professionals. No longer is health care—or home care—merely for English-speaking, Anglo-Saxon, Judeo-Christian patients and families (36). These facts present additional challenges when considering assessment of pain and symptoms as well as issues related to beliefs about death in various cultures (37, 38). Assessment and treatment are complicated by cultural factors, and health care providers along with researchers seek ways to understand and accomplish a nonbiased medium from which to practice. Likewise, health care providers may be caught by the demands for individualized care in the midst of a growing multicultural society (39).

Notably, in many non-Anglo communities, it is tacitly acknowledged as a “duty” in the culture that the burden of much health care automatically shifts to the extended family. In theory this increases the number of caregivers, but it does not increase the certainty of training, understanding, or efficacy of home care. In such environments, familiarity with one’s ethnic, religious, or cultural beliefs—especially with respect to terminal care—is best appropriated within a person’s respective community. Not only is this true for the patient but also for the surviving family and community. It may justify transcultural home care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree