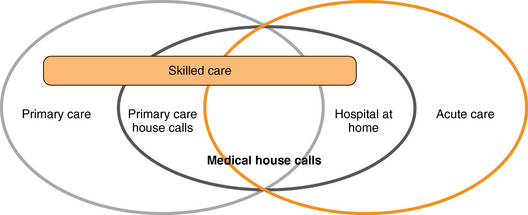

12 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the types of health care services available to older adults at home. • Understand the basic payment mechanisms for these services. • List evidence-based outcomes of home care for older adults. • Recognize the limitations of the existing evidence base on home care. • Identify key elements of recent legislation affecting medical home care. Home care in its most general sense refers to any diagnostic, therapeutic, or social support service provided to patients in their homes.1 These services may range from a visiting nurse checking vital signs and counting pills in prescription bottles, a physician or nurse practitioner evaluating and treating pulmonary edema, a speech therapist providing language rehabilitation, an aide bathing a terminally ill patient in home hospice, or a medical social worker helping caregivers identify and coordinate community services to help keep a patient in his or her home instead of moving into institutional long-term care. Table 12-1 shows the array of home care services available. TABLE 12-1 Medicare, the major insurer for older Americans, makes an important distinction among the services listed in Table 12-1 and defines “skilled” care as care that is “reasonable and necessary” and required on an intermittent basis. Furthermore, Medicare pays for skilled home care only if a patient is homebound (i.e., leaving the home requires considerable and taxing effort, and absences from home are infrequent or of brief duration).2 It is important to note that Medicare does not cover personal care unless it is in the context of skilled care. Therefore, a patient who requires assistance only for activities of daily living, and does not have a need for skilled care, must find some other way to obtain and/or pay for these services. Medicaid covers personal care at home, usually for a few hours per day, several days per week, but has strict financial eligibility criteria that exclude many older adults who are not impoverished. In addition to these formal services that are directly funded by various insurance payors, informal unreimbursed care provided by family and friends is crucial to keeping patients at home, and represents a silent but enormous economic force in the U.S. health care system.3 In this chapter, we describe the two most common types of formal home care: Medicare skilled home care and medical house calls. We also briefly describe Hospital at Home, an emerging model of acute care in which intensive home-based medical management substitutes for a hospital inpatient admission, and the Independence at Home demonstration project included in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. Figure 12-1 depicts the continuum and overlap of the various major types of home care. The light gray circle on the left represents the population of older adults who receive primary care services from physicians and other medical providers. Most of these patients are seen in the office, but some of them receive primary care visits at home (dark gray circle), and are sometimes referred for skilled home care (gold bar) for additional home-based rehabilitation or medical management and monitoring. Some patients experience acute illness (gold circle) which is managed at home through medical house calls or Hospital at Home, often in conjunction with skilled care (intersection of gold bar with light gray, dark gray, and gold circles). Another important group of patients who can benefit from home care may not be homebound by Medicare’s skilled home care definition, but are medically complex or have medical conditions refractory to the usual office-based management. Although these patients may not be eligible for skilled home care, a targeted medical house call by a physician or nurse practitioner to assess adherence, functional conditions, caregiver/patient dynamics, and other barriers to effective care can provide invaluable context for the medical provider, and open up new opportunities to work with the patient to optimize care. In fact, one study comparing office-based medical and psychiatric evaluations with in-home assessments showed that a substantial minority of patients had important problems that were discovered only on the home visit, and almost all patients had problems identified at home that increased the risk of morbidity or significant functional decline.4

Home care

What is home care?

Skilled Home Care

Medical/Other House Calls

Personal Care

Nursing

Therapy

Physical

Occupational

Speech

Medical social work

Primary care home visits

Podiatry

Dentistry

Optometry

Hospital at Home

Home hospice

Bathing

Dressing

Feeding

Toileting

Who needs home care?

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine