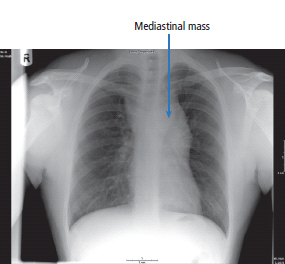

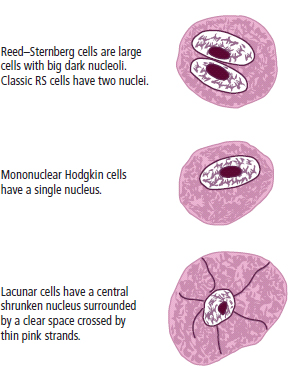

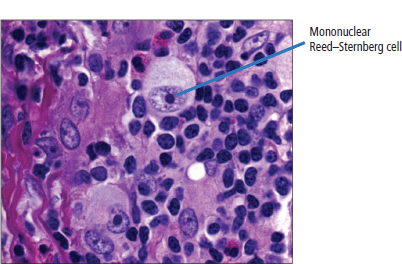

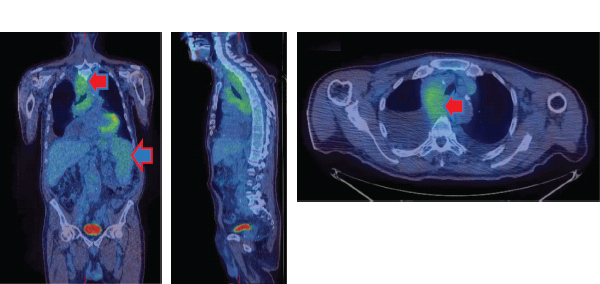

29 Hodgkin’s disease or Hodgkin’s lymphoma was first named by Samuel Wilks who was Thomas Hodgkin’s successor as curator of the medical museum at Guy’s Hospital. Hodgkin’s original description of seven patients was published in 1832. The physicians in charge of the care of these seven patients included Thomas Addison (who described both Addison’s disease of the adrenals and Addison’s anaemia, which is better known as pernicious anaemia), Richard Bright (who described Bright’s disease of the kidneys) and Robert Carswell (who described multiple sclerosis but failed to get the illness named eponymously after him). As you recall from Chapter 1 only three of the original seven patients actually had Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a relatively uncommon tumour, affecting approximately 1845 people in 2011 in the United Kingdom (Table 29.1). Currently, there are 300 deaths annually, including, in 2002, the original Albus Dumbledore actor Richard Harris whose hit record “MacArthur Park” you will all of course remember (although probably as the 1978 Donna Summer version rather than the 1968 original). More men than women develop Hodgkin’s disease, and there is a bimodal age distribution with peaks in the third and seventh decades. Little is known of the risk factors for the development of Hodgkin’s disease, although there are minor associations with Down’s syndrome and smoking. Geographical clustering has been noted, and there have been a few familial cases of Hodgkin’s disease. The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome may be found incorporated within Reed–Sternberg (RS) cells, and about half of the cases of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the United Kingdom are linked to EBV. The Reed–Sternberg cell is pathognomonic for the diagnosis and is thought to originate from lymphocytes affected by EBV. There is significant interest in the origins of the Reed–Sternberg cells, which are large cells with multinucleated or bilobed nuclei that according to histopathologists look like owl’s eyes (Figure 29.1). Reed–Sternberg cells have a specific immunophenotype, expressing CD15 and CD30, but not expressing CD20 or CD45. Immunoglobulin gene expression is mutated within Reed–Sternberg cells, and there are functional rearrangements that lead to abnormal immune function. Table 29.1 UK registrations for Hodgkin lymphoma cancer 2010 This leads to defective apoptosis, prolonged B-cell survival and, ultimately, to the development of Hodgkin’s disease. EBV proteins remain present in about 40–50% of Reed–Sternberg cells and there is a threefold increased risk of Hodgkin’s disease, following infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever). This possibly suggests that EBV is a future target for immunotherapy. There is a 10-fold increase in Hodgkin’s disease in people living with HIV, but only a twofold to fourfold increase in allograft transplant recipients. Hodgkin’s disease is also associated with various autoimmune diseases including: Figure 29.1 Owl’s eyes. Histopathological sample demonstrating a Reed–Sternberg cell (a large binucleated cell with prominent nucleoli surrounded by a clear space or lacunae) diagnostic of Hodgkin’s disease. The presentation of Hodgkin’s disease is usually with enlarged lymph nodes. This is generally painless and may be accompanied by constitutional symptoms that include profound night sweating, sufficient to drench bedclothes, fevers greater than 38°C and weight loss exceeding 10% of body mass. These constitutional symptoms are prognostically important and designated as B symptoms. There are other non-specific symptoms relating to the presentation of Hodgkin’s disease, including alcohol-related pain and skin itching. These B symptoms are thought to be generated by cytokine release. In clinic, a careful history should be obtained and an examination made. Investigations will be organized which include a full blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), liver and renal function tests, a chest X-ray, CT scan of the chest and abdomen and bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy. The patient will be reviewed in outpatients with the results of these tests. Admission will then be organized for a biopsy of the lymph glands. The purpose of these investigations is to define the clinical stage of the disease and that of biopsy to make a histological diagnosis. The examination of bone marrow is commonly undertaken during the investigation of patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Less than 5% of men and women with Hodgkin’s disease have bone marrow involvement, however, and this is generally only present in patients with advanced tumours of stages greater than IIB. There are strong arguments against carrying out this assessment except in advanced-stage patients and with increasing use of PET–CT in staging, marrow assessment is being phased out in most centres. Figure 29.2 Hodgkin’s disease with a mediastinal mass. This chest X-ray of a 20-year-old male student shows infilling of the aortopulmonary window and a wide left paratracheal stripe due to mediastinal lymph node enlargement from Hodgkin’s disease. The investigation of Hodgkin’s disease is a recapitulation of the history of imaging in the United Kingdom. Plain X-rays (Figure 29.2) remain helpful, but approaches such as lymphography and staging laparotomy with splenectomy have been replaced by CT and MRI, whilst marrow examinations are being replaced by PET–CT scanning. Two forms of Hodgkin’s lymphoma are recognized: classical and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Figure 29.4). Four different histological variants of classical Hodgkin’s disease are described (see also Figure 29.3): Figure 29.3 The cells of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma has the immunophenotype of B-lymphocytes (CD20+ve, CD15−ve, CD30−ve) and few if any Reed–Sternberg cells. The results of the staging investigations will help the clinician to determine the clinical stage of the Hodgkin’s disease, and this in turn defines treatment. In stage I Hodgkin’s disease, one lymph node or two contiguous lymph node groups are affected. In stage II disease, two non-contiguous lymph node groups on the same side of the diaphragm are affected. In stage III Hodgkin’s disease, lymph node groups on both sides of the diaphragm are affected. In stage IV disease, there is extranodal spread to the liver, lung or bone but rarely to other sites (see Box 3.1). The tumour is further classified as A or B. “A” defines a lack of constitutional symptoms and “B” indicates the presence of the constitutional symptoms of Hodgkin’s disease. Finally, the staging is defined by use of the subscript “S”, which indicates splenic involvement, or “E”, which defines extension to involve extranodal tissue in direct apposition to an enlarged lymph node group (Figure 29.5). Figure 29.4 Hodgkin lymphoma. The purpose of staging is to define treatment groups. Since most patients will be cured of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, mortality from treatment-related toxicities has become a major determinant of treatment strategies. Patients with early stage disease (stages I and II) are usually treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the amounts depend on whether the patient has favourable or unfavourable prognosis disease. This is determined by a combination of age, disease sites, ESR and B symptoms. Patients with advanced stage disease (stages III and IV) are treated with combination chemotherapy. In the past, radiation treatment was generally given according to two well-defined treatment plans. Lymphadenopathy above the diaphragm was treated with mantle radiation which includes the lymph node groups in the neck, axillae and chest to a total dosage of 3500 cGy given over a period of 4–6 weeks. Infradiaphragmatic radiation is generally given in the inverted Y distribution that includes the para-aortic and iliac nodal groups. Treatment is given to a total dosage of 3500 cGy over a 4–6-week period. Mantle radiotherapy may be complicated by radiation pneumonitis, which is characterized by a period of breathlessness and fever and responds to steroids. It is invariably accompanied by loss of saliva production and oesophagitis. Infradiaphragmatic radiotherapy may be complicated by some minor bowel disturbance but generally is well tolerated. Radiation is usually avoided in children and adolescents as it may lead to gross growth disturbance. Infradiaphragmatic radiation may cause sterility. Figure 29.5 FDG–PET images of a patient with mediastinal lymph nodes and splenic involvement by Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He had significant weight loss and night sweats (stage IIIB). In view of the toxicity of radiotherapy, current practice is initial treatment with two to four cycles of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy restricted to the involved field site of initial disease. Combination chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease was introduced in the mid-1960s. The original treatment regimen, which has the acronym MOPP, combined mustine, vincristine (Oncovin), prednisone and procarbazine. These drugs are given intravenously and orally for 2 weeks and repeated every 4 weeks. Six cycles are administered. Treatment is associated with acute nausea and vomiting, sterility in 90% of males and 50% of females, and the development of second tumours in approximately 5% of patients. Chemotherapy treatments have been modified over the years in order to reduce side effects. Six is a “magic number” in oncology, and it is possible that in some cases fewer cycles of therapy are as effective as six cycles. The most frequently used current programme is called ABVD which combines adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine. The efficacy of this regimen was initially disputed as it was described by Italians but proven in an excellent clinical trial based at Harvard. These drugs cause neither sterility nor second malignancies and are of obvious advantage in a disease where there is a high expectation of cure. The initial randomized trial has been followed by further trials which have shown an equivalence of ABVD to standard therapy with MOPP and to hybrid therapies such as the higher dose but shorter duration Stanford V. High-dosage chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell support is the standard treatment for relapsed Hodgkin’s disease. The most commonly applied current programme in the United Kingdom uses “mini-BEAM” or BEAM (carmustine (BCNU), etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) chemotherapy. Since this chemotherapy wipes out bone marrow reserves, these must be replenished with stem cell infusions. These stem cells are normally autologous blood progenitors harvested prior to the procedure and frozen until needed. Autologous stem cell transplantation in centres of excellence has treatment-related mortality rates of 1–2%. Long-term remissions occur in up to 40% of patients. The evidence base for any benefit for high dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue in this situation is scant and the side effects of transplantation significant. A Cochrane analysis published in 2013 found that there were only three randomized trials of this approach which involved a total of just 398 patients. The meta-analysis concluded that there probably was a progression-free survival advantage to intensive therapy, but recommended more studies to prove the benefit of this treatment. In patients who are unsuitable for stem cell transplantation, an alternative approach for drug-resistant Hodgkin’s disease uses a novel immunoconjugate, Brentuximab vedotin. Brentuximab is a monoclonal antibody to CD30 that is linked to a cytotoxic antitubulin agent. So it delivers this toxin directly to the Hodgkin’s cells that it targets because they express CD30. The results of treatment of Hodgkin’s disease are considered to be one of the miracles of modern oncology, in that approximately 90% of patients with small-volume, early-stage disease are curable with radiation and between 40% and 60% of patients with advanced disease are curable with chemotherapy. A poorer prognosis results from the presence of bulk disease, constitutional symptoms or poor-prognosis histology. The patient who is “cured” as a result of treatment is unfortunately at risk from late relapse; this may occur 15–30 years after diagnosis. This risk of a late relapse is small and largely confined to lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease. Hodgkin’s disease is a tumour with significant cure rates, occurring in young people with an expectation of prolonged survival. This leads to a significant onus for providing a therapy that is without major long-term toxicity. Conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease using alkylating agents is associated with the development of second tumours. The incidence of second tumours reaches approximately 5%, with staggering increases in the rates of acute leukaemias and lymphomas. The leukaemias present early, 2–4 years after the completion of chemotherapy. The solid tumours, such as breast, colorectal and lung cancer, occur late, sometimes 15–20 years after diagnosis. Sterility is also an important consequence of treatment with any alkylating agent-containing regimen, reaching up to 80% in males and 50% in females. This is a very serious consideration in the design of future treatment programmes to improve upon cure rates in this condition. Case Study: The medical student.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Leukaemia

0.6

0.6

>20th

>20th

1 in 500

1 in 500

+21%

+11%

84%

83%

Presentation

Investigations

Pathology

Staging

Treatment and side effects

Radiation

Chemotherapy

Haemopoietic stem cell transplantation

Prognosis

Complications of chemotherapy

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree