60 Hodgkin’s Disease

Epidemiology and Risk Factors1

Hodgkin’s disease accounts for less than 1% of cancers diagnosed in the United States each year.2,3 There is a slight male predominance. The median age at the time of diagnosis is 26 to 30 years. The disease is uncommon in children younger than 10 years and the age-adjusted incidence is bimodal.4 Both peaks, at ages 20 to 24 and 75 to 84, show an annual incidence of approximately 5.5 cases per 100,000. A recent decline in the height of the incidence peak for older adults may be attributed to improved diagnostic accuracy and the ability to differentiate mixed cellularity or lymphocyte depletion Hodgkin’s disease from diffuse large-cell or anaplastic large-cell lymphomas.

There are no well-defined risk factors related to the development of Hodgkin’s disease.5 Older reports associating an increased risk with tonsillectomy have been refuted. There are no definite associations between Hodgkin’s disease and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci. The slight increased risk associated with small sibship size and higher degree of education has not been explained, but contributes to the hypothesis of an infectious cause. A relationship between Hodgkin’s disease and prior infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been proposed. Components of the EBV genome have been detected in the cellular deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of Reed-Sternberg cells,6 and elevated levels of immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin A against the EBV capsid antigen and elevated levels of antibody against the EBV nuclear antigen and early antigen D have been detected in the serum of patients who later develop Hodgkin’s disease.7 The risk for developing Hodgkin’s disease appears to be higher in the presence of a prior history of infectious mononucleosis.8 Evidence of prior EBV infection is most common in mixed cellularity Hodgkin’s disease and in pediatric Hodgkin’s disease in underdeveloped countries.9

Pathologic Conditions10,11

The cell of origin of the Reed-Sternberg cell is likely a precursor B cell. In most instances, the Reed-Sternberg cells stain positively for CD30 and CD15. They also express the interleukin 2 receptor (TAC) and HLA-DR antigens. They stain negatively with the leukocyte common antigen; occasionally, they are positive for pan–B cell markers such as CD20.12,13 However, the lymphocytic (L) and histiocytic (H) cells (Reed-Sternberg equivalents) in lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease are strongly positive for CD20 and CD45, but negative for CD15.14 There are five histologic subtypes of Hodgkin’s disease, according to the World Health Organization modification of the Lukes and Butler system. These include nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s disease and four subtypes of classical Hodgkin’s disease: nodular sclerosis, lymphocyte-rich, mixed cellularity, and lymphocyte depletion.15

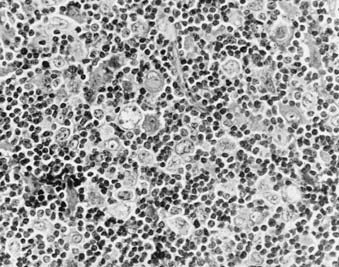

Nodular lymphocyte predominance (Fig. 60-1) is characterized by an abundance of normal-appearing lymphocytes and a paucity of abnormal cells. Patients frequently present with limited disease (stage I-II), and systemic symptoms are uncommon (<10%). The natural history of lymphocyte predominance is the most favorable among the histologic subtypes. In some reports, it demonstrates a pattern of late relapse similar to that of the low-grade lymphomas.16 However, the degree to which management programs should be influenced by this observation is not clear. In addition, these patients are at increased risk to develop transformation to other B-cell lymphomas, such as diffuse large-cell lymphoma. These observations, coupled with the different staining characteristics of the L and H cells of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease, suggest that this entity may actually be a form of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.14,16

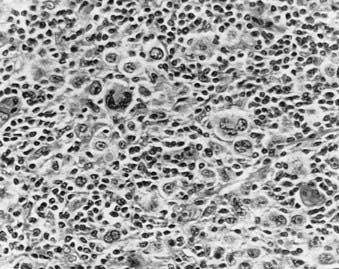

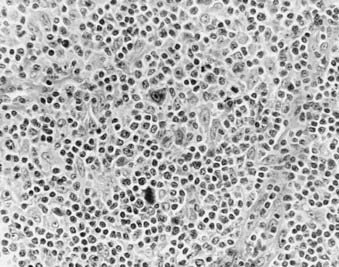

Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin’s disease (Fig. 60-2 and Fig. 60-3) is the most common histologic subtype in the United States (>70%). Involved nodes are traversed by broad bands of birefringent collagen surrounding nodules of cells that include lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, tissue histiocytes, and a variable proportion of atypical mononuclear cells and Reed-Sternberg cells. Women are more commonly affected than men, and the median age is younger than for other histologic subtypes. Clinically, the mediastinum and neck are often involved. One-third of patients have B symptoms. The natural history is somewhat less favorable than that of lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease.

Mixed-cellularity Hodgkin’s disease (Fig. 60-4) is characterized by a diffuse effacement of lymph nodes by lymphocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells, and there are relatively abundant atypical mononuclear and Reed-Sternberg cells. Patients with mixed-cellularity Hodgkin’s disease tend to present with more advanced disease and tend to be slightly older than those with nodular sclerosing or lymphocyte-predominant disease. The natural history of mixed-cellularity Hodgkin’s disease is less favorable than that of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease.

Interfollicular Hodgkin’s disease refers to a pattern of focal involvement of a lymph node in which there is a small focus of Hodgkin’s disease in the interfollicular zone. It is easy to confuse these cases with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.17

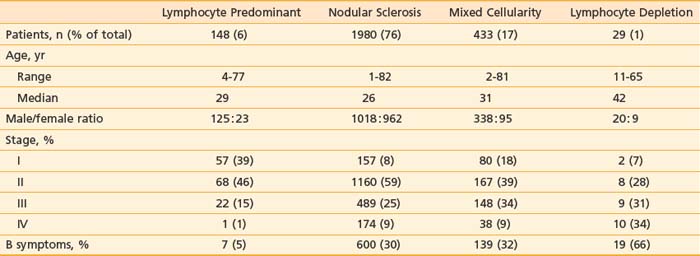

Table 60-1 summarizes the characteristics of 2590 patients treated at Stanford University from 1968 to 2001, according to histologic subtype. Other large centers in the United States and western Europe report a similar distribution of cases. However, the distribution of histologic subtypes from South America, Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and even some parts of the United States includes a greater proportion of unfavorable histologic types with a more aggressive clinical behavior.18

Clinical Presentation and Routes of Spread

Assuming contiguity between the supraclavicular lymph nodes and upper paraortic nodes–celiac axis–spleen (via the thoracic duct), 90% of patients with Hodgkin’s disease present with contiguous sites of involvement.19 The pattern of relapse among patients treated with irradiation alone also supports the concept of contiguity.20 Visceral involvement may be secondary to direct extension (especially lung, bone, or soft tissue) or hematogenous spread (such as to liver or multifocal bone).

The mechanism of spread of disease to the spleen is unclear. However, there is a correlation between the burden of disease identified in the spleen and the likelihood of hematogenous dissemination. Nearly all patients with hepatic or bone-marrow involvement by Hodgkin’s disease have (or had) extensive involvement of the spleen.21

Hodgkin’s disease only rarely involves the lymphoid tissues of the Waldeyer ring and Peyer patches. In addition, although visceral involvement by Hodgkin’s disease may be identified in the lungs, liver, bone marrow, and skeletal system, it uncommonly involves other organ systems such as the upper aerodigestive tract, central nervous system, skin, and gastrointestinal tract.22

One-third of patients present with fever, night sweats, or weight loss (B symptoms). Fevers may have a classic intermittent Pel-Ebstein pattern. The night sweats may be drenching. The presence of B symptoms often signals more extensive disease; however, even patients with only one or two involved lymph node regions may have significant B symptoms. Patients who have both weight loss and fevers may have a particularly poor prognosis.23

Patient age may have an effect on the natural history of the disease. In the elderly, the presence of intercurrent illness often affects the selection of staging and treatment procedures.24

Hodgkin’s disease may be diagnosed during pregnancy, and it is common for pregnancy to follow successful treatment. However, there is no evidence that pregnancy has any effect on the natural history of Hodgkin’s disease in these women.25,26

Although patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) do not appear to be at increased risk for the development of Hodgkin’s disease, patients infected with HIV-1 who develop Hodgkin’s disease display an unusual natural history. The disease tends to present in a more advanced stage, is more likely to be associated with systemic symptoms, and often has unusual patterns of involvement.27 Treatment is challenging because these patients have a poor tolerance for chemotherapy and opportunistic infections are common.

Diagnostic and Staging Studies28,29

Staging procedures commonly employed for Hodgkin’s disease are listed in Table 60-2. Routine hematologic evaluation may reveal a mild anemia, lymphopenia, leukopenia, leukocytosis, or thrombocytosis. These may reflect paraneoplastic effects, but in some cases may be indicative of bone marrow involvement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase levels may be elevated and serve as useful markers to assess response to treatment and subsequent disease activity.30 Serum albumin levels, white blood cell counts, and lymphocyte counts are all important prognostic factors, especially in advanced disease.31

Table 60-2 Staging Procedures in Hodgkin’s Disease

Blood work—CBC, differential platelet count, ESR, albumin, chemistry screen including liver function studies and LDH |

CBC, Complete blood cell count; CT, computed tomography; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; 18FDG-PET, 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

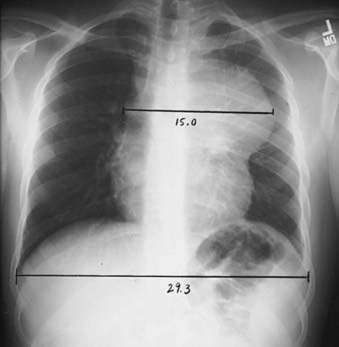

Radiographic evaluation should include posterior-anterior and lateral chest radiographs. A convenient means for measuring the extent of mediastinal adenopathy is to divide the maximum single width of the mediastinal mass by the maximum intrathoracic diameter (near the level of the diaphragm), as shown in Fig. 60-5. When this ratio exceeds 1 : 3, the disease is defined as bulky.32 Other measurements have also been used to define bulky mediastinal disease, including mass diameters that exceed 10 cm. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest should also be obtained if there is mediastinal disease, because it provides ancillary information regarding the extent of intrathoracic disease and assists in treatment planning and follow-up assessment.33

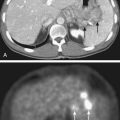

Abdominal and pelvic CT scans should be obtained with special attention paid to the retroperitoneal area, spleen, and liver. Lymph nodes are generally considered to be enlarged on a CT scan if their short axis measurement exceeds 1 to 1.5 cm. Splenomegaly or hepatomegaly alone does not equate with involvement by Hodgkin’s disease, because enlarged spleens are often uninvolved at the time of splenectomy; however, the presence of nodules visible on CT scan is considered indicative of involvement. The overall accuracy rate for detection of Hodgkin’s disease in the spleen by CT was reported to be only 58% in a laparotomy series.34 However, these data, obtained at a time when staging laparotomy was routine, may underestimate the detection rate with current CT scanning technology.

In the last several years,35 positron emission tomography (PET) using 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (18FDG) has been acknowledged as an important initial staging study in Hodgkin’s disease. FDG-PET is more sensitive than CT scanning36 or gallium imaging37 and is more convenient than gallium as a staging procedure because of the shorter interval between injection and scanning (1 hour versus 48 to 72 hours). PET scanning will identify additional sites of disease, beyond those identified by other clinical evaluation and imaging, in 10% to 15% of patients. PET scanning has proved to be highly useful as an early response indicator. When repeated early in the course of therapy, its prognostic value exceeds that of other well-established prognostic factors.38 PET is also useful as a follow-up study to evaluate residual masses present on CT scan.39

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an alternative to chest or abdominopelvic CT scanning for initial staging, but has not been employed widely. Its main value may be in the staging evaluation of pregnant women with Hodgkin’s disease.40

Staging System41–44

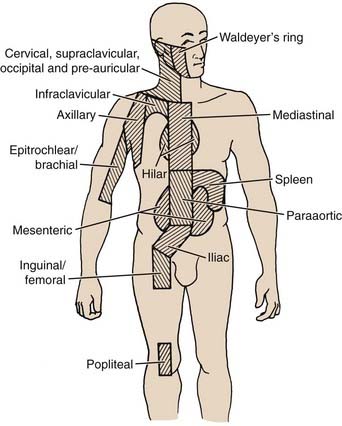

The Ann Arbor staging system for Hodgkin’s disease is outlined in Table 60-3.45 The lymphoid regions used in this system are displayed in Fig. 60-6. The designation of clinical stage (CS) is based on results of the initial biopsy and clinical staging studies, whereas the pathologic stage (PS) is based on the results of any subsequent biopsies, including bone marrow biopsy and laparotomy and splenectomy. In the postlaparotomy era, the distinction between CS and PS is rarely noted. Significant systemic (B) symptoms include fevers, night sweats, and weight loss. Other systemic symptoms of Hodgkin’s disease, including pruritus, alcohol-induced pain, and fatigue, should be noted, but are not considered B symptoms. The E designation indicates extralymphatic disease, although the concept is very poorly defined. In practical clinical terms, an E lesion is often considered to be a direct extension from involved lymph nodes and encompassable by a curative radiation field; however, the original description includes as an example “multiple nodules in the lung limited to one lobe.” In addition, the Ann Arbor system fails to deal with the possibility of multiple E lesions, which can be identified quite clearly in the chest with the careful use of contemporary imaging studies such as CT and MRI. Some authors’ inclusion of these patients in stage IV has led to a great deal of confusion in the literature. Another deficiency of the Ann Arbor system is its failure to consider bulk of disease. This has been shown to be important, especially in the mediastinum. The presence of bulky disease in the mediastinum should be noted, together with the stage.

Table 60-3 Ann Arbor Staging Classification System

| Stage I | Involvement of a single lymph node region |

| Stage II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (II) or localized involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site and of one or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (IIE) |

| Stage III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (III), which may also be accompanied by involvement of the spleen (IIIS) or by localized involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site (IIIE) or both (IIISE) |

| Stage IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs or tissues, with or without associated lymph node involvement |

The absence or presence of fever, night sweats, or unexplained loss of 10% or more of body weight in the 6 months before diagnosis is denoted by the suffix letter A or B, respectively.

Patients are assigned a clinical stage based on the initial biopsy and all subsequent nonsurgical staging studies. A pathologic stage is assigned based on all clinical studies as well as subsequent surgical staging procedures such as bone marrow biopsy, staging laparotomy, and splenectomy.

From Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Mushoff K, et al: Report of the committee on Hodgkin’s disease staging classification, Cancer Res 31:1860, 1971.

In addition to Ann Arbor stage, other indicators may be helpful in predicting prognosis or selecting therapy. An international study evaluated prognosis in advanced Hodgkin’s disease by analyzing prognostic features among 5141 patients.31 Seven factors were identified, each of which had a similar prognostic affect. These are summarized in Table 60-4.

Table 60-4 A Prognostic Score for Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease

| Factor | Unfavorable Covariate |

|---|---|

| Serum albumin | <4 g/dl |

| Hemoglobin | <10.5 g/dl |

| Gender | Male |

| Age | 45 years and older |

| Stage | IV (Ann Arbor) |

| Leukocyte count | >15,000/mm3 |

| Lymphocyte count | <600/mm3 or <8% of white count |