HIV prevention in people who inject drugs

According to the CDC, 9% of incident HIV cases in the United States are directly attributable to injection drug use [ ]. Among people who inject drugs (PWID), the risk for HIV and other blood-borne pathogens is primarily related to injecting behaviors, including sharing needles, syringes, and other injecting and drug preparation equipment. Data from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System reflects that approximately 34% of PWID share syringes and 58% share other injection paraphernalia [ ]. In the setting of ongoing and untreated substance use, PWID also experience heightened risk for HIV related to sex because of (1) sex in the context of intoxication with associated disinhibition, (2) high-risk sex networks, and/or (3) sexual bartering (i.e., exchanging sex for drugs, money, goods, or other services). Women who inject drugs experience “double risk” for HIV because of overlapping sex and drug use networks [ ]. HIV risk among PWID is compounded by concomitant infections with hepatitis B and C that are more prevalent in PWID (a topic addressed more completely in Chapter 6 and 2).

PWID not only experience inordinate risk for HIV but also face numerous barriers to engaging with effective prevention and treatment services for HIV. Despite the high HIV risk, PWID often have less access to prevention innovations because of stigmatization, underinsurance, poor socioeconomic status, homelessness, criminal justice involvement, and other challenges navigating systems of care and support. In the setting of the current opioid epidemic, in which there are increasing numbers of PWID, particularly in nonurban settings, access to harm reduction and HIV prevention resources is often limited. As multiple recent hepatitis C virus and HIV outbreaks in the United States illustrate, PWID experience a high burden of HIV risk, particularly when resources are not available or accessible to reduce harms associated with injecting [ , ].

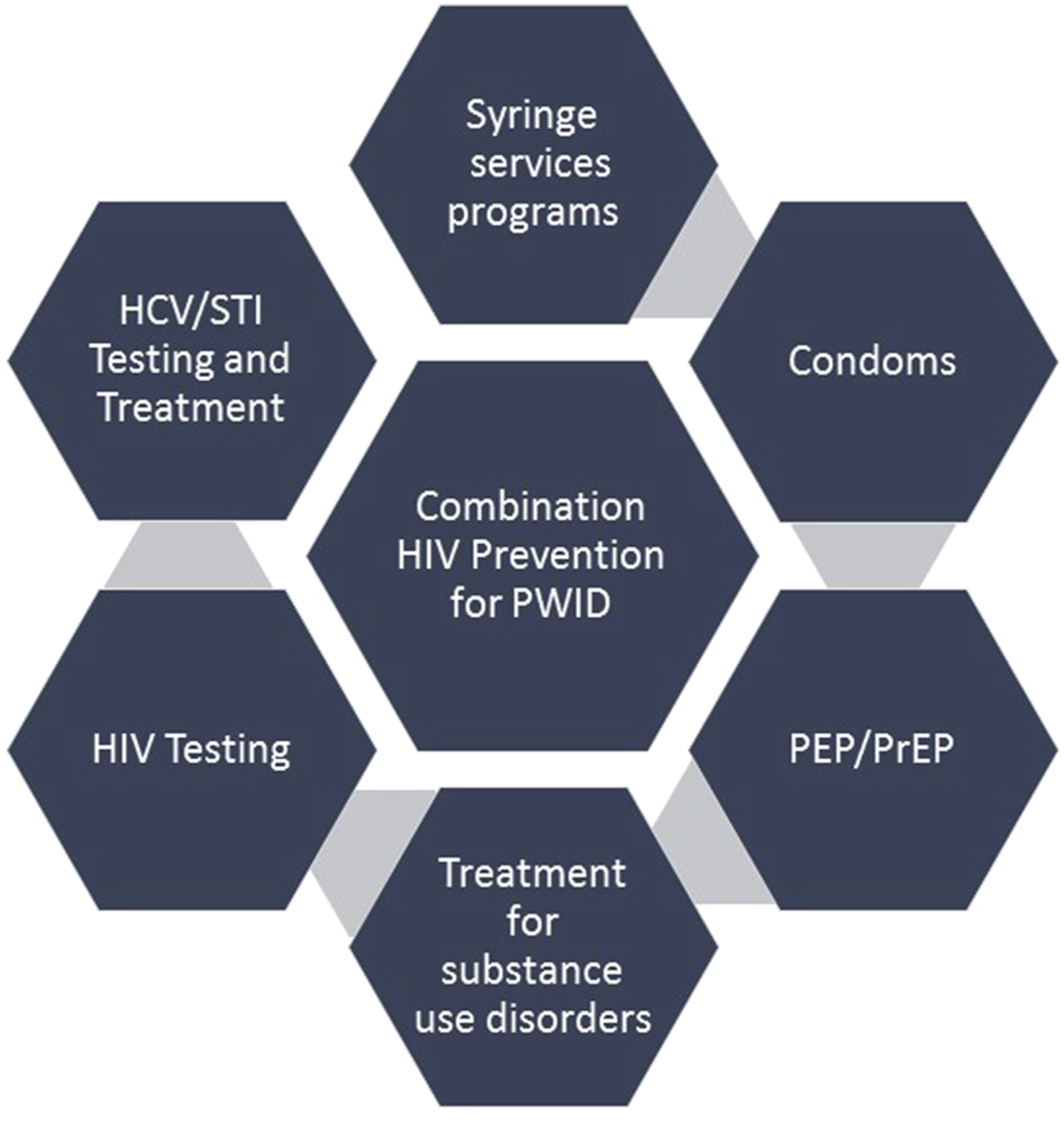

PWID are a key target population for HIV prevention in the global and US national strategies [ , ]. A number of evidence-based HIV prevention approaches are available for PWID, including treatment for opioid use disorder with medication-assisted therapy (MAT), syringe services programs (SSPs) for harm reduction, frequent testing for HIV and sexually transmitted infections, and barrier protection (i.e., condoms) to reduce HIV risk associated with sex. Outcomes are optimized when these approaches are used together, known as “combination prevention” ( Fig. 11.1 ).

In light of the US opioid crisis, multiple methods of HIV prevention are needed for PWID. HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an important addition to the HIV prevention armamentarium for PWID. PrEP is grounded in the principle that giving antiretrovirals to people without HIV (but who are at high risk for acquiring HIV) is effective in preventing infection in spite of exposure, as is the case of prevention of maternal to child transmission of HIV. At present, the only FDA-approved medications for PrEP are tenofovir diphosphate (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF]) or tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) given in combination with emtricitabine (FTC). Co-formulated TDF/FTC (manufactured by Gilead and sold as Truvada) or TAF/FTC (manufactured by Gilead and sold as Descovy) are available as single-tablet daily medication. Other dosing strategies (e.g., “on-demand” pericoital dosing) and formulations (e.g., TDF 1% vaginal gel) are investigational in select populations or not yet widely used in the United States. In a meta-analysis, TDF alone was shown to be equally effective as TDF/FTC. Other medications for PrEP, including injectable cabotegravir and a dapivirine vaginal ring are currently in development and testing. In multiple large randomized clinical trials of men who have sex with men (MSM) and serodiscordant heterosexual couples, PrEP was significantly effective at preventing HIV when it was taken consistently [ ]. In this chapter, we review the evidence and indications for PrEP in PWID and discuss strategies to address key challenges to scale-up.

Evidence of efficacy of preexposure prophylaxis in people who inject drugs

To date, there has been a single large randomized clinical trial for PrEP in PWID, known as the Bangkok Tenofovir Study (BTS) [ ]. The BTS was a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Thailand. The study population was recruited from 17 Bangkok Metropolitan Administration drug treatment clinics and composed of 1924 men and 489 women who had injected drugs in the past year, excluding pregnant women, people with chronic hepatitis B, and people already diagnosed with HIV-1. About 22% of participants were receiving methadone at study baseline. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either TDF 300 mg ( n = 1204) or placebo ( n = 1209) and participants could choose to receive study drug as a 28-day supply for self-administration or as daily directly observed therapy. Adherence was determined by direct observation (for those opting for this delivery strategy) or by dried blood spot testing for TDF levels. Risk behavior was repeatedly analyzed to look for evidence of possible risk compensation. Over 9665 person-years of follow-up, there were 17 new HIV infections in the TDF group and 33 new infections in the placebo group. Thus compared with placebo, TDF was associated with a relative risk reduction of HIV infection of 48.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.6%–72.2%; P = .01). Participants with high adherence, categorized as taking the medication at least 71% of prescribed days (approximately 5 days per week), had a 73.5% (95% CI, 16.6–94.0; P = .03) risk reduction. In other subgroup analyses, TDF had higher efficacy in women than men (78.6%; 95% CI, 16.8%–96.7%; P = .03) and in participants aged 40 years or more compared with those aged <40 years (88.9%; 95% CI, 41.1%–99.4%; P = .01). Reported sexual and injecting risk behavior decreased significantly overall during the trial. Side effects were minimal, with the treatment arm experiencing nausea and/or vomiting at a higher rate than the control.

The BTS established the efficacy of TDF in a high-risk population of PWID but has not been replicated to date. There are a number of possible reasons why additional large-scale randomized controlled trials of PrEP have not been conducted among PWID. One is the concern about the ethics of providing PrEP to PWID in settings where other harm reduction tools, such as MAT for opioid use disorder or SSPs, are not available, including in global regions where HIV incidence is rising and is primarily attributable to injection drug use [ ]. The other concern about a randomized controlled trial of PrEP among PWID is that study recruitment would require people to disclose their ongoing injecting behaviors, which is not only highly stigmatized but also criminalized, including in the United States [ ].

Preexposure prophylaxis effectiveness in the “real world”

In the absence of other clinical trials for PrEP efficacy, data from demonstration projects support PrEP effectiveness in the “real world” and can provide guidance on PrEP implementation. For example, in the open-label extension of the BTS, known as BTS-OLE, 798 (60%) of originally enrolled participants chose to continue on PrEP. Those who were aged 30 years or more, injected heroin, or had been incarcerated in prison during the trial more often chose to continue on PrEP, suggesting PrEP might be acceptable to PWID at the highest risk of HIV who would benefit from it the most [ ]. In preliminary outcome data, the HIV incidence rate in participants not on PrEP was 0.7 per 100 person-years compared with 0.5 per 100 person-years in the group on PrEP, yielding a significant protective benefit of PrEP in this high-risk population of PWID [ ]. Although not exhaustive, an updated list of large-scale PrEP demonstration and implementation projects in United States and international settings is maintained online [ ] and on ClinicalTrials.gov for federally funded studies.

Additional evidence for PrEP in PWID is derived from mathematic modeling studies. Published data support the cost-effectiveness of PrEP for PWID, particularly when it is combined with expanded HIV screening strategies and early treatment for those found to have HIV, averting up to 26,700 new infections and reducing HIV prevalence by up to 14% among PWID in the United States [ ]. Another modeling study found that the most cost-effective approach to HIV prevention for PWID combines PrEP for HIV prevention with naloxone for overdose prevention and linkage to addiction treatment [ ]. Sustainable cost-effectiveness of PrEP for PWID depends on pharmaceutical drug pricing and enrollment strategies [ ].

Indications for preexposure prophylaxis in people who inject drugs

Since the FDA approval of TDF/FTC in 2012 and based on data from the BTS, the CDC has developed clinical guidance on PrEP indications for PWID [ ]. Because PWID may experience HIV risk not only from injecting but also related to high-risk sex, PWID may meet PrEP eligibility criteria in one or more categories of risk ( Box 11.1 ).

An adult person or adolescent weighing ≥35 kg without established HIV infection meets at least one of the following sets of HIV risk criteria:

| Risk from injection drug use | Risk from MSM | Risk from heterosexual sex |

|---|---|---|

| Injecting of any nonprescribed substance in the past 6 months | A man with any male sex partners in the past 6 months | A man or woman with any opposite sex partners in the past 6 months |

| AND shared injecting or preparation equipment | Not monogamous with an HIV− man | Not monogamous with an HIV− partner |

| At high risk for relapse, including among people on MAT | AND any anal sex (receptive or insertive) without condoms in the past 6 months | AND infrequently uses condoms with a partner of unknown HIV status, who is HIV+, or who is at high risk of HIV (PWID, MSM) |

| Recent bacterial STI | Recent bacterial STI | |

| Any transactional sex | Any transactional sex |

To assess people for PrEP, healthcare providers need to be prepared to accurately and comprehensively evaluate risk. This requires a nonjudgmental approach to screening in order to foster trust, encourage disclosure, and prevent further stigmatization of PWID. Although the US Preventive Services Task Force does not currently recommend universal screening for PrEP eligibility or HIV, they do recommend that providers prescribe PrEP if they deem patients to be at sufficiently high risk for HIV [ ]. To assess HIV risk, providers should inquire whether patients

- 1.

have injected any drugs not prescribed to them in the past 6 months;

- 2.

have shared needles, syringes, or other injecting or preparation equipment (e.g., cotton, “cookers,” syringes for splitting or sharing drugs, etc.);

- 3.

are on MAT (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone);

- 4.

are at short-term risk of relapse to injection or noninjection drug use;

- 5.

engage in condomless sex with high-risk partners (MSM, PWID, transactional sex, unknown HIV status, HIV+, and not virally suppressed);

- 6.

have had a recent bacterial sexually transmitted infection (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis).

If in the course of a behavioral risk assessment, patients disclose ongoing injection drug use, they should be offered access to harm reduction services (including SSPs and overdose prevention with naloxone) and treatment for opioid use disorder (including MAT if indicated). Per clinical care guidelines, in addition to conducting a behavioral risk assessment, providers should perform baseline HIV testing and phlebotomy for renal function testing. Because PWID often experience housing instability, underinsurance, partner violence, unemployment, and criminal justice involvement, wraparound services need to be in place to address these issues in addition to PrEP provision. PrEP is a program not a drug.

The HIV prevention or preexposure prophylaxis care continuum

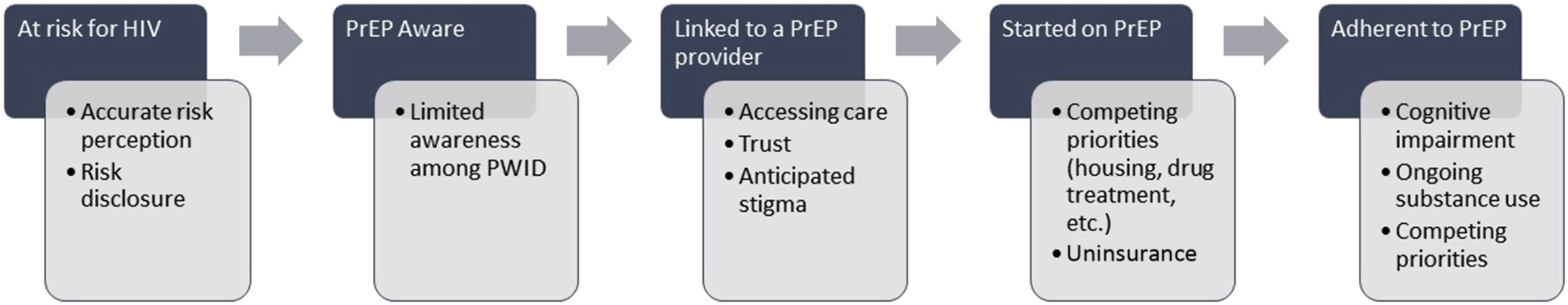

The current prevailing model of PrEP delivery parallels the HIV care continuum [ , ]. In this model, patients must first be identified as being “at risk” for HIV infection. This requires an accurate self-perception of personal risk and disclosure of risk behaviors to a possible PrEP provider or referral source. Patients must also test negative for HIV. If patients and their providers are aware of PrEP, they can be linked to PrEP care. Although PrEP services have traditionally been the domain of infectious disease clinicians (who have experience prescribing TDF/FTC as part of a treatment regimen for HIV), PrEP scale-up demands expansion of the pool of potential providers, including to primary care [ ]. A limited pool of potential PrEP providers is especially limiting for PWID [ ]. Because the PrEP care continuum is predicated on patients actively engaging with healthcare providers and traditional systems of care, PWID face several challenges at every step ( Fig. 11.2 ).

Major challenges to PrEP care engagement for PWID in the prevailing model of care include competing priorities, such as co-occurring medical conditions (hepatitis C, sexually transmitted infections), psychiatric conditions, substance use disorders, and social conditions that each require treatment and intervention. If left undiagnosed and/or undermanaged, these conditions can interfere with the ability of PWID to access and be retained on PrEP. Although ideally care for these co-occurring conditions is integrated into PrEP delivery programs, at a minimum, PrEP providers can screen, briefly intervene, and refer to treatment (SBIRT). Perhaps in part because of these barriers to engagement in the PrEP care continuum for PWID, there is a translational efficacy-effectiveness gap in PrEP among PWID. Although an estimated 72,000–115,000 PWID would qualify for PrEP based on current clinical criteria [ ], <1% have actually received it since TDF/FTC was approved as PrEP in 2012 [ ].

Challenges facing scale-up and widespread adoption

Individual barriers

At the individual level, an increasing number of studies have identified low knowledge of the existence of PrEP among PWID [ ]. For example, a study conducted by Stein et al. [ ] among PWID in Massachusetts found that only 7% of PWID were aware of PrEP, yet once informed, 47% were willing to take it to reduce their chances of HIV acquisition. Likewise, research among opioid-dependent patients enrolled in a methadone maintenance program in Connecticut found awareness of PrEP to be low (18%) but nearly two-thirds (62.7%) were willing to initiate PrEP once the PrEP-related information deficit was corrected [ ]. A study has further explored individual-level cognitive barriers, including beliefs about PrEP, concerns about taking PrEP and its side effects, and PrEP perception [ ]. Many PWID consider themselves at low risk for HIV infection despite reporting risk behaviors (e.g., sharing of injection equipment, condomless sex, multiple sex partners) [ , ]. Additional concerns about PrEP side effects and health consequences, including how PrEP might reduce the efficacy of other medications (e.g., antidepressants, methadone), has negatively impacted overall PrEP scale-up for PWID. Moreover, the significance of competing priorities in the lives of PWID, including the demands imposed by physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms, has been a challenge for PrEP utilization [ ].

Interpersonal-level barriers

Interpersonal-level barriers to PrEP utilization and widespread scale-up include negative experiences from interacting with healthcare providers and HIV-related stigma within social networks. PWID also report anticipated stigma within their social, sexual, and drug networks, worrying that others would think they were HIV infected if they were seen using PrEP [ , ]. For example, Shrestha and Copenhaver [ ] reported a similar concern among PWID that taking PrEP could lead others to believe they are HIV infected and are on antiretroviral therapy (ART), which would negatively influence their uptake and adherence to PrEP. Other studies have noted the potential social risks (e.g., discrimination, exclusion, loss of trust) of taking PrEP as evidenced by experienced and enacted stigma, which contribute to low PrEP uptake among PWID. For example, Biello et al. [ ] found negative experiences from interacting with healthcare providers as an important interpersonal-level barrier to PrEP utilization. Interactions of PWID with healthcare providers were overwhelmingly negative, and several described experiencing stigma or mistreatment that made them reluctant to disclose their drug use or other risk behaviors when seeking PrEP care. Furthermore, distrust from healthcare providers because of unsubstantiated concerns about poor adherence has led to poor PrEP access for PWID [ , ].

Clinic- and structural-level barriers

Studies have indicated various important barriers to PrEP scale-up at the clinic and broader structural levels. Lack of access to and utilization of healthcare contribute to the slow PrEP uptake observed among PWID. Previous studies have established a widespread lack of prescribing providers and poor infrastructure for PrEP delivery, and clinicians have been shown to lack knowledge on PrEP or willingness to provide PrEP to PWID [ ]. Even when PWID are able to access healthcare, their providers may not have the training or resources to facilitate PrEP education or uptake. For example, in a qualitative study, some providers shared their reluctance to prescribe PrEP to PWID because of concerns of risk compensation and suboptimal adherence [ ]. Barriers at the broader structural level include issues related to lack of money or identification to fill prescriptions, homelessness, criminal justice system involvement, and transportation difficulties [ ]. Although the majority of PWID have some form of health insurance, many private insurance plans have high monthly deductibles that can impact the ability of individuals to afford treatment. Furthermore, the drug assistance program (offered by Gilead, who produced Truvada) for people without insurance does not cover additional costs, including copays and cost of laboratory tests and doctor visits. Therefore in states without Medicaid expansion, these costs associated with PrEP are an important disincentive to uptake. Even if they successfully start PrEP, PWID may encounter challenges related to action planning and medication logistics, such as having to take a pill every day and seeing a provider regularly, as well as counseling support to stay on PrEP.

Strategies for preexposure prophylaxis scale-up among people who inject drugs

Low-threshold access to preexposure prophylaxis

The traditional PrEP care model is a multistep process that requires long waits and multiple clinic visits before PrEP is prescribed. This complex process, along with other patient-specific factors, discourages individuals from returning to the clinic to receive PrEP prescription. One potential strategy to address this barrier would be to encourage earlier linkage to care by utilizing rapid linkage to care protocols. In the case of HIV treatment, several randomized clinical trials [ ] have demonstrated the feasibility, acceptability, safety, and efficacy of same-day ART initiation (also known as “test and treat”) [ ]. Same-day access to PrEP is a safe and feasible strategy to initiate PrEP care among patients attending sexual health clinics [ , ]. Rapid PrEP initiation may be particularly important for PWID, as they remain a hard-to-reach group and are more likely to lose to follow-up before treatment initiation.

mHealth-based approaches

mHealth, which refers to the use of mobile and wireless technologies to improve health, holds significant promise for PrEP scale-up, given the widespread mobile phone ownership among PWID. Several studies have evaluated the use of mHealth interventions (e.g., text messaging, phone calls, web-based, or app-based) to optimize PrEP uptake among key populations. It is a promising and cost-effective strategy to increase access to PrEP services. It also helps promote prevention and treatment behaviors by allowing for private communication and incorporating flexible reminders and content [ ]. Particularly for PWID, leveraging mHealth-based approaches will help reduce individuals’ discomfort and distrust of disclosing their sexual behavior to providers, will address the low cultural competency of providers for working with individuals of diverse sexual identities, and will circumvent challenging compliance with rigid clinic scheduling.

Using nonphysician prescribers for preexposure prophylaxis scale-up

One crucial consideration to facilitate wide-scale PrEP implementation in PWID is the way in which healthcare professionals can be organized to optimize its delivery and management. Nonphysician prescribers, such as nurse practitioners (NPs), are the most common points of contact for individuals accessing healthcare and are specially trained to improve the health of vulnerable populations through a unique, holistic approach that emphasizes community health, health education and prevention, and social well-being [ ]. Research suggests that NPs can manage 80%–90% of care provided by primary care physicians [ ] and that they are more likely than physicians to practice with vulnerable populations, including in rural areas where the opioid epidemic is currently focused [ ]. Importantly, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated that NPs tend to provide more information to patients and that NPs are equivalent to physicians in terms of patient satisfaction, safety, and health outcomes [ ]. Given this evidence, leveraging NP assets in the delivery of PrEP care is a step toward closing the gap in the adoption of PrEP as a prevention practice among key populations, including PWID [ ].

Integrating preexposure prophylaxis with other treatment services

Clinics and programs that only or mainly offer PrEP and fail to provide other services to make long-term engagement desirable are more likely to experience high drop-off. Prior research suggests that providing PrEP in the context of a wide range of programs and clinical services is crucial to adherence and retention [ ]. For example, substance abuse treatment settings (e.g., methadone clinic) are fundamental to the adoption and delivery of PrEP and the implementation of PrEP research, through their roles in counseling and coordination of care with clients’ primary care providers [ , , ]. Likewise, SSPs have great potential to engage their at-risk clients in PrEP through counseling and referrals and may also effectively promote adherence to PrEP through counseling and monitoring.

Patient education and empowerment

As noted earlier, lack of awareness of PrEP can be a critical barrier to PrEP uptake. Limited PrEP knowledge among PWID may reflect that PrEP marketing and, to a lesser extent, public health information campaigns have intensively targeted other populations, especially MSM, leading to misperceptions about the appropriateness of PrEP for PWID [ ]. Information that is accessible and acceptable to this population is needed to increase the knowledge of PrEP availability and specific aspects of daily adherence, side effects, and the protections that are and are not provided. This information should be available in key areas that high-risk PWID frequent (e.g., SSPs and other community-based organizations, homeless shelters, and public transportation). In particular, SSPs and community-based organizations that work with this population and employ trusted staff and mobile outreach teams could help with the diffusion of PrEP information into PWID networks [ ]. Furthermore, strategies that align HIV risk perceptions and actual behaviors may also be needed to increase PrEP interest in some high-risk individuals [ , ]. For example, counseling involving motivational interviewing could help individuals recognize and discuss their HIV risks, increase their motivation for HIV risk reduction, and improve their knowledge of PrEP. Interventions involving motivational interviewing could also help develop self-efficacy for PrEP use and other behavioral skills [ , ].

Advances in preexposure prophylaxis modalities and the future of preexposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs

Although a daily oral TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC pill are the only approved and recommended forms of PrEP, there is growing interest in developing new methods for administering antiretroviral drugs as prevention. The past several years have witnessed a surge of research in the development of additional modalities of PrEP [ ], which could be important to fill the HIV prevention gap in PWID. In order to minimize potential adherence barriers associated with taking daily oral PrEP, particularly forgetting due to competing priorities, cognitive impairment (associated with chronic substance use), and anticipated stigma related to inadvertent disclosure, new PrEP modalities are being developed and tested. Specifically, with the safety and acceptability of cabotegravir for long-acting injectable PrEP now established [ ], large-scale clinical trials are underway to test its efficacy when given once every 2 months. Additional advances, such as parenteral formulations of injectable antiretrovirals and infusible antibodies, may increase the simplicity of PrEP delivery, potentially requiring injections or infusions every few months [ ]. These approaches, as well as the advent of generic TDF/FTC, could decrease some of the costs associated with PrEP compared with daily regimens and make it more scalable for PWID.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree