increased in people with HIV due to frequent coinfection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use. Many of these tumors have established viral associations. While certain common cancers such as breast or colon cancer are not more common in HIV-infected individuals, the burden of these NADM is also increasing as the population infected with HIV ages. Information on optimal treatment approaches to these cancers in the setting of HIV infection is needed.

I. KAPOSI SARCOMA (KS)-ASSOCIATED HERPESVIRUS AND ASSOCIATED TUMORS

A. KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also called human herpesvirus-8, is a gammaherpesvirus related to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). KSHV is the causal agent of three tumors: KS, multicentric Castleman disease (MCD), and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL). KS derives from endothelial cells, and MCD and PEL from B-lymphocytes. KSHV infection occurs endemically in certain regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa and parts of the Mediterranean basin, and at lower levels worldwide. In the United States, KSHV seroprevalence is generally low, but the rate is more than 15% in men who have sex with men (MSM). In the immunocompetent host, clinical manifestations of KSHV infection are uncommon. However, HIV infection and other forms of immunodeficiency substantially increase the risk of KSHV-associated malignancies.

B. KS

1. Epidemiology. KS is a multifocal angioproliferative tumor. The tumor is comprised of spindle cells and infiltrating mononuclear cells around leaky vascular slits; blood in these slits gives KS its characteristic coloration. Clonality studies in KS are conflicting. Generally, it is thought to be oligoclonal or polyclonal, but it may have a monoclonal component, especially in advanced disease. Four epidemiologic categories of KS are described, each caused by KSHV. Classical KS is an uncommon, generally indolent tumor predominantly seen in older men in the Mediterranean basin. Endemic KS occurs in Africa and more often develops in women and younger patients. Iatrogenic KS occurs in solid organ transplant patients and other patients on chronic

immunosuppressive agents. AIDS-associated KS is also called epidemic KS. After peaking in the early-1990s, epidemic KS incidence declined rapidly in developed countries, likely due to the use of nucleoside anti-HIV therapy and then cART. It is the second most common tumor in people with HIV/AIDS in the United States. In sub-Saharan Africa, where prevalence of both HIV and KSHV is high and access to cART remains limited, KS remains one of the most common tumors.

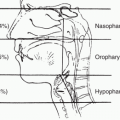

2. Presentation and patient evaluation. Early KS usually manifests as red, purple, or brown papules or plaques on the skin or mucous membranes. Lesions may occur at any site but there is a predilection for the extremities, ears, nose, and palate. Advanced lesions are often nodular and may become confluent or ulcerate. Involvement of lymph nodes and dermal lymphatics leading to edema is seen in advanced cases and may result in permanent impairment. KS involvement of visceral organs such as the lungs or gastrointestinal tract and effusions in serous body cavities are other manifestations of advanced disease. Gastrointestinal KS may present as occult blood loss or with other gastrointestinal symptoms. Pulmonary disease may manifest with cough, dyspnea, or hemoptysis, and may be life threatening. Radiographic findings in the chest include reticulonodular or nodular infiltrates, with or without effusions, and may be difficult to differentiate from infection. Endoscopy and bronchoscopy are useful in visually demonstrating luminal lesions. Given the risk of bleeding, endobronchial biopsy is rarely performed. The natural history of KS is variable, and even in the absence of treatment, KS commonly waxes and wanes.

Evaluation of a patient with KS should focus on the extent of disease, KS-associated symptoms (pain, edema, disfigurement, secondary infections), rate of progression, association with cART, and the use of immunosuppressive agents including glucocorticoids. Other important factors include the history of HIV treatment, opportunistic infections, nadir and current cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) lymphocyte counts, and HIV viral load. Physical exam should include documentation of the extent of cutaneous and mucosal involvement, evaluation of lymph nodes and spleen, fecal occult blood test for occult gastrointestinal blood loss, and baseline chest radiography for asymptomatic pulmonary involvement. A biopsy should be performed when possible to exclude other cutaneous processes. Computed tomography (CT) scans and endoscopy are not indicated unless the initial evaluation suggests visceral disease. Pathologic evaluation of pleural effusions or lymphadenopathy should be performed when feasible, if present. Patients with KS are at elevated risk of PEL and MCD, and physicians should be alert for these tumors (see subsequent discussion).

TABLE 25.1 AIDS Clinical Trials Group Staging for Epidemic KS*

Relative Risk

Good Risk (0)†

Poor Risk (1)‡

Disease status

Tumor (T)

Confined to skin, minimal oral disease, or both

Edema; extensive oral ulcers; visceral and gastrointestinal disease

Immune status (I)a

CD4 count ≥150/μL

CD4 count <150/μL

Systemic illness (S)

No prior opportunistic infection or thrush; no B symptoms

Prior opportunistic infection or thrush; B symptoms; performance status <70%; other HIV-related illness

KS, Kaposi sarcoma.

*Modified by validation study.

† Requires all in this column.

‡ If any in this column.

3. Staging. KS is a multicentric tumor that does not fit TNM categorization. Prior to the availability of cART, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group developed and validated a staging system that reflects various prognostic factors (Table 25.1). Patients are defined as good (designated with subscript 0) or poor (designated with subscript 1) risk on the basis of tumor burden (T), immune function assessed by CD4 count (I), and systemic illness (S) assessed by history of opportunistic infections, systemic symptoms, and performance status. Before the availability of cART, patients who were poor risk in any category were considered as being at poor risk overall. In the post-cART era, CD4 count is a less important prognosticator, and two overall risk categories are utilized: patients with a heavy burden of disease and systemic illness (T1S1) are poor risk compared to all other patients (T1S0, T0S1, or T0S0). Patients with pulmonary involvement have the highest risk of death and may require urgent evaluation and therapy.

4. Treatment. All patients with HIV-associated KS should receive cART. The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines for treatment of HIV provide current information on topics including optimal drug therapy and interactions at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/. Effective HIV suppression and immune reconstitution can lead to sufficient tumor regression, especially in patients with limited (T0) disease, and it can improve response durability and overall survival in patients with any stage disease. However, some patients have initial worsening of KS on starting cART, believed to be due to immune reactivation syndrome.

A number of other therapies are effective in KS and should be considered in light of the risks, potential benefits, and needs

of each individual patient. KS is not curable, and the goal of therapy is to induce durable responses or minimize the extent of disease while minimizing toxicity. Some patients, especially those with severe KS and low CD4 counts, may require intermittent therapy for years. Most patients with HIV-associated KS will either respond to cART or require systemic therapy, and local therapy is now rarely used. Systemic therapy is generally indicated for bulky, rapidly progressing, symptomatic, or life-threatening disease. In addition, it is worth considering for patients with disfiguring or other psychological distressing disease manifestations. Except for diagnostic biopsy, surgery is rarely indicated in settings where cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs are available.

a. Local therapy. Radiotherapy including electron beam therapy, topical therapy, cryotherapy, or intralesional injection of vinblastine or other cytotoxics can be used for localized KS. Topical alitretinoin 0.1% gel is specifically approved for this indication. The overall response rate with 12 weeks of therapy is 35% to 37%. Radiation therapy is also highly effective for local control; it is generally reserved for disease that is limited but causing severe pain or distress. Short-term local toxicities are usually manageable, but radiation can lead to “woody” skin and other long-term ill effects. Doses range from an 8 Gy single dose to fractionated therapy to a total of 16 to 30 Gy and are individualized for a given patient.

b. Systemic therapy

(1) Chemotherapy. Several cytotoxic chemotherapy agents are effective, providing rapid improvement in KS-related symptoms in the majority of patients (Table 25.2). Liposomal doxorubicin (20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) is generally the agent of choice. It is equivalent or superior in activity to older regimens containing bleomycin and vincristine, with or without doxorubicin, and less toxic. An absolute neutrophil count of 750 cells/μL is adequate to deliver therapy, although granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) support between cycles may be necessary. Treatment should generally be continued until maximal response is obtained. Treatment duration is variable. If possible, patients should not receive a cumulative lifetime anthracycline dose of over 550 mg/m2 because of the risk of severe, irreversible cardiotoxicity. The sense of some practitioners is that the risk is less with a liposomal formulation; however, this dose should not be exceeded without careful cardiac monitoring and an awareness of the risks involved.

TABLE 25.2 Selected Systemic Treatment Regimens for KS

Regimens

Chemotherapy

Commonly used dosing regimen

Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil)

20 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks

Paclitaxel

100 mg/m2 IV every 2 weeks, or135 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks

Biologic response modifier

Interferon-α2b

1-10 x 106 IU/d SC

IV, intravenously; KS, Kaposi sarcoma; SC, subcutaneously.

For second-line therapy, paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 every 2 weeks or 135 mg/m2 every 3 weeks has produced response rates of 50% to 70% when used without cART. Paclitaxel is substantially more toxic than liposomal doxorubicin, especially in patients with HIV-associated immunosuppression, and careful monitoring of blood counts is required. Caution should be used with medications that inhibit CYP3A4, such as protease inhibitors, or CYP2C8 (including trimethoprim), as these may increase the toxicity, and paclitaxel dose reduction may be necessary.

Lastly, oral etoposide 50 mg/day for days 1 to 7 of a 14-day cycle is active, with an overall response rate of 36% in previously treated patients, the majority of whom were not receiving cART. This may be particularly useful in resource-limited settings. Monitoring of complete blood counts is required.

(2) Immune modulators. Interferon-α (IFN-α) is the best-studied immunotherapy in KS. Responses have been reported with doses ranging from 1 × 106 IU/day to 36 × 106 IU three times per week (see Table 25.2). Common side effects include cytopenias and elevated transaminases. Fatigue, fevers, and flulike symptoms are common but decline with continued therapy and can be managed with acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients should be monitored for depression and hypothyroidism. Most practitioners begin with low-dose IFN-α, 1 to 5 × 106 IU subcutaneous injection daily, and gradually increase the dose as tolerated.

C. KSHV-associated MCD (KSHV-MCD)

1. Epidemiology. There are several forms of Castleman disease, including a unicentric hyaline-vascular form, a multicentric plasma cell form, and a multicentric form associated with KSHV. Nearly all Castleman disease arising in the setting of HIV infection is KSHV-MCD. This polyclonal hyperproliferative B-cell disorder is considered to be rare, although its incidence is not well defined. In contrast with KS, there is evidence that MCD has become more common since the advent of cART. While most commonly seen in the setting of HIV, KSHV-MCD may occur in elderly or immunocompromised patients.

2. Presentation. KSHV-MCD is characterized by intermittent flares of inflammatory symptoms, including fevers, fatigue, cachexia, and edema, together with lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly. Gastrointestinal symptoms and cough are also common. Flares are often severe and can be fatal. Many symptoms are attributable to a KSHV-encoded viral interleukin-6. There is no validated staging or prognostic system. KSHV-MCD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with HIV and unexplained inflammatory symptoms or autoimmune phenomena, particularly anemia or thrombocytopenia. The clinical course waxes and wanes, but untreated, it is frequently fatal within 2 years of diagnosis, with patients succumbing to the severe inflammatory syndrome or progressing to lymphoma.

3. Evaluation. Diagnosis of KSHV-MCD generally involves an excisional lymph node biopsy, including demonstration of characteristic pathologic changes and KSHV-infected cells by immunohistochemistry. Physical exam should focus on adenopathy, splenomegaly, edema, and evaluation for concurrent KS. Common laboratory abnormalities include anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, hyponatremia, and elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is generally not elevated. Patients with MCD should undergo CT of neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis.

4. Treatment. There is no standard therapy for KSHV-MCD. HIV-infected patients should receive cART. Several agents have reported activity in case series or small studies. Perhaps best studied is the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab. Most patients respond initially to rituximab-containing regimens, although relapses are common. Rituximab monotherapy may be insufficient in advanced disease, and it has been associated with exacerbation of intercurrent KS. Other potentially active agents include ganciclovir, IFN-α, and NHL chemotherapy regimens. Survival of over 2 years is now relatively common. However, given the many uncertainties in managing patients with KSHV-MCD, consideration should be given to referral to a clinical trial.

D. Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL)

1. Epidemiology. PEL is a rare variant of B-cell NHL notable for its unusual presentation and aggressive clinical course. The great majority of reported cases occur in people with HIV, where it represents less than 4% of all lymphomas.

2. Presentation. PEL usually presents as a lymphomatous effusions in serous body cavities, frequently in patients with other KSHV-associated malignancies. Many cases are pleural, but peritoneal, pericardial, and leptomeningeal presentations are seen. Extracavitary PEL may rarely present in other locations, including lymph nodes and the gastrointestinal tract.

3. Evaluation. Diagnosis of PEL depends on the demonstration of KSHV infection of tumor cells. In more than 70% of cases, tumor cells are coinfected with EBV. Common B-cell surface markers (CD19, CD20, CD79a) are absent, while activation markers (CD30, CD38, CD71, CD138) are often present; presence of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements confirms B-cell monoclonality. Evaluation of disease extent should be performed as for NHL (see Section II).