14. HIV

Clare Stradling

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter the reader will be able to:

• Appreciate the context, global impact and nutritional consequences of HIV infection;

• Evaluate the aetiology of the clinical manifestations of HIV infection including lipodystophy and dyslipidaemia;

• Be aware of the side effects associated with the use of antiretroviral therapies, in particular increased cardiovascular risk;

• Critically discuss the evaluation of cardiovascular risk and nutritional status in HIV-infected patients;

• Critically discuss the dietary and nonpharmacological interventions used to manage consequences of HIV infection.

Introduction

This chapter will aim to give a general overview of most aspects of HIV disease, focusing in detail on the metabolic complications. The needs of specific groups such as intravenous drug users, children and the management of coinfections are beyond the scope of this chapter and will not be covered.

A glossary and list of abbreviations is included at the end of the chapter.

Historical context

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) was first recognised in 1981, as a strange new disease, where previously healthy homosexual men became ill with severe weight loss and developed unusual infections such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) (see Tom Hanks in the film Philadelphia). In 1983 the causative agent, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a novel retrovirus, was identified and is thought to have resulted from a ‘species jump’ of nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) passed from monkeys to humans during bush meat hunting expeditions.

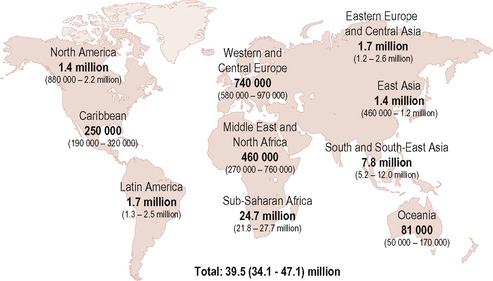

The early epidemic in North America and Western Europe may have been driven by sex between men, and individuals sharing drug-injecting equipment; but HIV continues its relentless global spread through heterosexual transmission. Twenty-five years on and with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), HIV infection has changed from a universally fatal condition to a manageable chronic illness. Yet unfortunately this is still not the reality for the majority of the 40 million people infected with HIV worldwide living in resource-poor countries where a diagnosis of HIV is seen as a death sentence.

In the UK, 78,938 individuals have been reported with HIV infection, of whom 47,517 accessed care in the UK during 2005. The estimated figures are much higher with one in every three UK HIV infections remaining undiagnosed (see Figure 14.1).

|

| Figure 14.1 • Reproduced with kind permission from UNAIDS (2006). |

HIV transmission

HIV is present in body fluids and is transmitted via contact with infected blood, semen or cervical secretions during unprotected sexual intercourse, sharing contaminated drug injecting equipment, transfusions of infected blood and mother to baby. Occupational infection from contaminated needles to healthcare workers remains exceptionally rare.

Pathogenesis of HIV infection

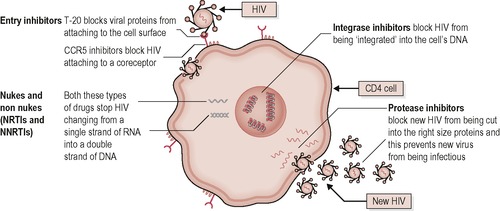

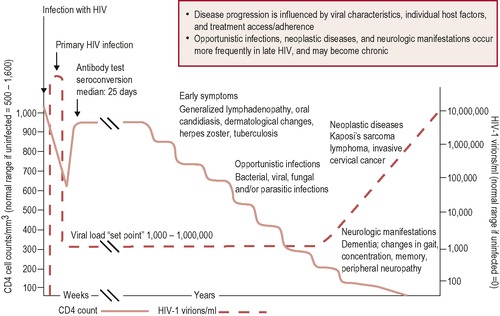

As a virus, HIV can only replicate by becoming part of the host cells. It does this by entering T lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages using a primary receptor (CD4 glycoprotein) on the surface of the cells (Figure 14.2). Once inside, the HIV viral core copies its RNA into DNA using reverse transcriptase and integrates with the DNA of the host cell, hijacking the cell processes to produce many more viruses. Viral replication with reverse transcriptase is error prone and characterised by a high spontaneous mutation rate. The initial phase of very rapid virus proliferation, with 10 9 new virus particles produced per day, activates the CD4 T lymphocytes to mount an immune response from B lymphocytes, producing antibodies, phagocytes and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, all with the aim of destroying the infected CD4 cells, which clears much of the virus in the acute phase (see Figure 14.3). After some time CD4 lymphocyte production fails to keep up with their relentless destruction which leads to reduced numbers and a dysregulation of the immune system, reducing the body’s ability to mount an effective immune response to the infection. Consequently the infected individual is vulnerable to a host of normally benign opportunistic infections.

|

| Figure 14.2 • Reproduced from Introduction to Combination Therapy, May 2009, with permission of i-Base, http://www.i-Base.info |

|

| Figure 14.3 • |

Natural history of HIV progression

Immediately after HIV infection the virus replicates rapidly, causing a high viraemia and marked decrease in CD4 count (acute phase—Figure 14.3). This may be accompanied by transient flu-like symptoms of fever, rash and lymphadenopathy.

Following the acute phase:

• The CD4 cells recover, but not to previous levels, and reach equilibrium between viral replication and the host immune response approximately a year after infection (clinical latency in Figure 14.3).

• Once equilibrium is achieved CD4 cell counts and plasma HIV RNA levels (viral load) are used to monitor the progression of HIV disease.

As key prognostic indicators among untreated individuals infected with HIV, they have been likened to a steam train careering towards a fallen bridge, with the viral load (quantity of virus present in blood) representing the speed of the train and the CD4 count (measure of immune function) representing the length of remaining track. Viral load (VL) often remains fairly constant during this period of clinical latency, which varies widely among individuals and is characterised by a gradual decline in CD4 cell numbers, at approximately 60–100 cells/mL blood per year.

As the CD4 count drops, the infected person becomes increasingly susceptible to infection, and in the absence of antiretroviral treatment (ARV), immune system degenerates to a point where it becomes unable to mount an effective immune response to opportunistic infections or AIDS defining illnesses present in the everyday environment (AIDS phase—Figure 14.3). Typically at this stage the CD4 count is < 200 cells/mL.

Immune function of the gut

Although this gives an overall picture of what happens to the infected person, it is important to acknowledge the key role that the gut plays in the course of HIV disease progression. During the first few weeks of infection, HIV predominantly infects and destroys CD4 memory cells, found mainly in the gut mucosal lymphoid tissue. 1 This viral replication causes inflammation with T cell and epithelial cell apoptosis in the gut mucosa, resulting in significant damage to the integrity of the mucosal barrier. Translocation of Gram-negative bacteria, as a result of this increased gut permeability, may induce the immune activation that is a hallmark of pathogenic immunodeficiency virus infection. This association has yet to be proven as cause–effect, but it is clear that events in the gut mucosa are central and pivotal to the pathogenesis of HIV.

Nutrition, HIV and the immune system

Early epidemiological studies, in developing countries, established the link between nutrition and immune function, where malnutrition was associated with increased incidence and severity of infections leading to higher mortality rates. Nonetheless, specific nutrient excess via megadosing is not the solution as this can also depress immunity and increase susceptibility to infectious disease. Both deficiency and excess of specific nutrients have been shown to have deleterious effects on the immune system in HIV disease. 2 Interactions between nutrition, infection and immunity are complex and multidirectional, illustrated by the impact of infections, such as tuberculosis, on nutritional status via the immune system. In summary, many cofactors including other viral infections, cytokines and nutrition are likely to play a role in the progression of HIV disease by altering its natural course.

Nutritional therapy in early HIV infection

Historically HIV was characterised by wasting, of both lean body mass and fat, which was associated with shortened survival and diminished quality of life. 3 HAART has now transformed HIV to a chronic condition with greatly improved survival, requiring a shift in emphasis from prevention of weight loss to consideration of conventional diseases such as diabetes and heart disease.

Nutritional therapy in early HIV infection involves nutritional assessment with monitoring of body composition and advice regarding primary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, micronutrient intake and food hygiene.

Nutritional assessment

The methods utilised to monitor body composition have changed over time with the evolution of HIV disease. Historically regular monitoring of body weight was the priority in HIV care, allowing identification of acute or chronic weight loss, shown to be early indicators of underlying systemic or gastrointestinal infection respectively. 4 In conjunction with weight, bioelectrical impedance analysis or more simply, mid-arm muscle circumference was used to monitor loss of lean body mass, seen in wasting associated with AIDS-related illnesses.

With AIDS-related wasting, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scanning (DEXA) was adequate to distinguish fat loss from muscle wasting. But now more sophisticated cross-sectional imaging methods, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans, are required to quantify changes in visceral fat (VAT) and subcutaneous fat (SAT) seen in lipodystrophy (LD) and the more subtle fatty infiltration of the liver, heart and muscle. These methods are too expensive for routine clinical use; therefore waist circumference (WC) is the surrogate marker of choice, being more closely associated with VAT and central adiposity than BMI (see Chapter 18 on obesity). Although little agreement has been found between four actual methods of measuring WC, the self-reported WC estimates correlate adequately for monitoring purposes5 and have been found to mirror MRI results for VAT changes. 6

Likewise anthropometric measurements of four site skinfold thicknesses (triceps, biceps, subscapular and suprailiac) with the Durnin-Womersley formula has been validated against the criterion method of whole body MRI scanning to monitor lipoatrophy (LA) in this population. 7 Alongside global subjective assessment and patient report, early signs of lipodystrophy can easily be spotted and action taken to prevent worsening.

Other assessments

Assessment of cardiovascular risk, with full lipid profile and calculation of 10-year risk, is required due to increased risk of cardiovascular disease observed in this population (see p. 183). Similarly, evaluation of insulin resistance and changes in body fat distribution are necessary, with fasting glucose levels and waist circumference, respectively, due to their likely occurrence (see p. 181). Screening of the above is recommended at baseline, before commencing ARVs, 3–6 months later, and annually thereafter. 8 Routine screening for bone and renal disease is not currently recommended, but is likely to become an integral part of metabolic management in the future.

Primary CVD prevention

HIV infection is now a recognised risk factor for CVD; therefore dietary advice for people with asymptomatic HIV infection essentially reflects current primary CVD prevention guidance (see Chapter 19):

• At least 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity daily:

• Smoking cessation;

• Alcohol consumption limited to 3 units per day;

• At least five portions of fruit and vegetables daily;

• Dietary fat to provide no more than 30% total energy intake, replacing saturated fats with monounsaturated; and

• Two servings of omega-3 fatty acid-containing fish per week.

Micronutrients

Pre-HAART, general descriptive studies associated low micronutrient serum levels (low vitamin E, B 12, Se, vitamin A) and variable intakes (low B, high zinc) with adverse clinical outcomes. 2 Conversely zinc and selenium levels have been associated with improved virologic control in patients taking HAART. 9

Supplementation trials in resource-poor settings have shown some benefit on HIV-related death rates and reduced disease progression in those taking micronutrient versus placebo. 10,11 Whilst these results are encouraging it is conceded that they cannot be generalised to other HIV populations because the subjects had no access to antiretroviral therapy, and were potentially nutritionally deficient prior to supplementation. Hence a systematic review of 15 randomised controlled trials found no conclusive evidence that micronutrient supplementation effectively reduced or increased morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected adults. 12 Larger trials with sufficient duration of follow-up are required to describe the clinical benefits and adverse effects of micronutrient supplements in the long term, especially in individuals who are not yet symptomatic before we see routine prescription of micronutrients as the standard of care. 2,12

Food and water hygiene

General guidance on food storage, preparation and cooking practices, promoted by the Food Standards Agency (http://www.food.gov.uk; http://www.eatwell.gov.uk), is recommended for all patients. As the risk of food borne infections varies according to the degree of immunosuppression, patients with CD4 < 200 need to avoid high-risk foods as recommended to all vulnerable groups. The most common causes of bacterial diarrhoea in patients with HIV infection are Clostridium difficile, Shigella and Campylobacter jejuni.

Common sources of infection are: 13

• Listeria—mould-ripened soft cheese, cook chill/ready-to-eat foods from delicatessen counters;

• Salmonella—raw eggs, contact with pet reptiles;

• Campylobacter jejuni—cross contamination between raw and cooked food;

• Escherichia coli—unpasteurised dairy products, undercooked meat;

• Clostridium perfringens—meat dishes not reheated thoroughly;

• Bacillus cereus—rice dishes cooled slowly or kept warm;

• Toxoplasmosis—cat litter, undercooked meat;

• Cryptosporidium, Giardia and Shigella—changing nappies, handling pets, gardening and sexual practices (faecal–oral route).

Cryptosporidium parvum is a protozoan parasite that infects the gastrointestinal tract, causing acute enteritis, which is self-limiting when the immune system clears the infection at the mucosal surface. The course of the disease is closely linked to immunocompetence; thus when CD4 < 50 it can be a persistent and life-threatening infection with no effective treatment, highlighting the need to ensure that infection is avoided. 14 For this reason patients with CD4 cell counts < 200 are advised to boil water, from whatever source, before drinking it, as a measure for preventing water-borne cryptosporidiosis. 15 As boiling dechlorinates water, it then requires refrigeration and use within 24 hours.

Whilst bottled water and water from jug filters are unlikely to contain parasites, the lack of enforceable standards means that they may carry an increased bacterial load and should be avoided. 16 High levels of bacterial contamination were found in 40% of the 68 samples of commercially bottled mineral water tested. 16 When neither boiling nor filtering is possible, carbonated water bottled from a deep mineral source will offer some protection via the acidity reducing bacterial load.

Use of submicron filters installed to the mains water supply is the preferred method for provision of safe drinking water in hospitals, whilst provision of cooled boiled water is an alternative for older wards.

Probiotics

Small studies have supported the safety of use of probiotics containing lactobacilli or bifidobacteria in people with HIV infection with no increase in risk of opportunistic infection. 17 However, extreme caution is required in those with advanced disease where the risk of bacterial translocation is greater, evidenced by cases of bacterial sepsis from Lactobacillus acidophilus and cases of fungal sepsis from Saccharomyces boulardii. 17

The rationale for using probiotics for infectious diarrhoea is that they act against enteric pathogens by competing for available nutrients and binding sites, and increasing specific and nonspecific immune responses. Similarly, there may be a role in ARV-related diarrhoea, which was reduced by probiotics in combination with soluble fibre in one small study. 18

Whilst Lactobacilli might appear safe, generalisation cannot be made to other probiotics, as the properties of different species are strain specific and infections have been reported from Streptococcus, Enterococcus and Saccharomyces yeasts.

Untreated HIV

In the absence of HAART, the CD4 declines, allowing infection from opportunistic agents. There is a multitude of AIDS-defining illnesses affecting every system in the body as seen in Table 14.1.

| Directly or indirectly, HIV can affect every organ or system in the body. AIDS-defining illnesses, as defined by Category C of the Center for Disease Control classification system, are in italics (CDC 1993). | ||

| System affected | Clinical manifestation of HIV disease | Issues related to nutrition |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | Coccidiodomycosis Kaposi’s sarcoma Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia Tuberculosis | Pyrexia Lethargy Anorexia Rapid weight loss |

| Reproductive | Cervical cancer | Anorexia |

| Neurological | Cerebral toxoplasmosis Cryptococcal meningitis Cytomegalovirus retinitis HIV encephalopathy Peripheral neuropathy Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | Nausea and vomiting Confusion Loss of vision Pyrexia Cognitive impairment Depression Feeding difficulty |

| Endocrine | Pancreatitis | Nausea |

| Gastrointestinal | Oral hairy leukoplakia Candidiasis Herpes oesphagitis Salmonellosis Listeriosis Mycobacterial disease Cryptosporidiosis Isosporiasis Wasting syndrome | Sore mouth Altered taste perception Dysphagia Abdominal pain Diarrhoea Malabsorption Weight loss |

| Bone | Lymphoma Osteoporosis | Weight loss Reduced mobility |

| Muscle | Myopathy | Muscle wasting |

| Renal | HIV associated nephropathy (HIVAN) | Diet restrictions |

| Circulatory | Anaemia | Fatigue |

| All of the above | Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) | All of the above |

Patients who are unaware of their HIV status still commonly present with these illnesses in which malnutrition is a major complication and a significant prognostic factor in advanced disease. 3 HIV-related wasting is associated with poor outcomes including decreased muscle mass, strength, ability to function in daily living; increased mortality, infections and disease progression. The incidence of wasting has declined significantly with access to HAART, but remains a relevant phenomenon, with 5% involuntary weight loss doubling mortality risk. 19

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to go into detail about opportunistic infections. Suffice to say that the priority is the diagnosis and treatment of the underlying infection, but nutritional support should be commenced whilst waiting for results of diagnostic tests. The multidisciplinary team will provide a supportive role offering symptomatic control, minimising drug side effects and improving functional impairment. The dietitian’s role is to optimise nutritional status by:

• Meeting increased nutritional requirements;

• Optimising nutritional intake; and

• Limiting malabsorption and alleviating gastrointestinal symptoms.

Nutritional therapy is indicated when the BMI is < 18.5 kg/m2 or when there is significant weight loss (> 5% in 3 months) or a significant loss of body cell mass (> 5% in 3 months) has occurred. 20 The application of nutritional support and utilization of skills from all other clinical areas is required in a progressive manner for the management of patients with opportunistic infections:

• Nutritional counselling;

• Oral nutritional supplements;

• Tube feeding including PEG; and

• Parenteral nutrition.

Standard formula should be used except in cases of diarrhoea, where medium chain triglyceride formulae improve stool frequency and consistency. 20 There are many anecdotal reports of improved tolerance with peptide-based formulae and those containing soluble fibre, but these are not supported by published evidence. 21

In the changing face of HIV disease, death from ‘classical AIDS’ occurs predominantly in those who are diagnosed late when already acutely ill. Conversely, those in the UK who know their status and access HIV care die from causes not directly related to HIV; most commonly cancer, liver disease due to hepatitis B or C coinfection and/or alcohol and CVD. Globally, other issues predominate such as the increasing incidence of tuberculosis in Africa due to high prevalence of HIV.

With increasing migration and the global spread of HIV infection, consideration of immigration status, financial security, housing and availability of traditional foods becomes vital in order to provide culturally relevant dietary advice. Engaging with the individual to achieve adherence to nutritional and ARV treatment requires acknowledgement of differences in health beliefs and cultural practices.

Local and regional names of African carbohydrate staples

• Yam or plantain

○ Fufu—West Africa

• Cassava

○ Banku or kenkey—West Africa

○ Gari—Nigeria

○ Manioc—Central Africa

• Green banana

○ Matoke—Uganda

• Flat bread

○ Kisera—Sudan

○ Chambo—Malawi

○ Injera—Ethiopia and Eritrea

• Maize meal

○ Asida—Sudan

○ Ugali—Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania

○ Uji—Kenya

○ Sadza—Zimbabwe

○ Nsima—Zambia, Botswana, Malawi

○ Mealie pap—South Africa

Treated HIV and ARVs

Although the first ARV (zidovudine) was used as a treatment in 1987, it was not until protease inhibitors (PIs) were developed in 1996 that adequate suppression of viral replication could be achieved using a combination of three different ARVs or highly active antiretroviral therapy. Despite dramatic reductions in morbidity and mortality it was not without its challenges, when long-term side effects emerged (see below) and evidence that near perfect adherence was required in order to maintain viral suppression. As HAART evolves over time the ideal time to start therapy is constantly re-evaluated incorporating outcomes other than survival, such as level of immune reconstitution, risk of cancers and heart disease.

Use of ARVs has implications for dietitians, all of these are crucial to assist in adherence to drug regimens and maintenance of viral suppression:

1. Timings of drugs need to be tailored to suit the patient’s daily routine and meal pattern.

Many ARVs have food restrictions to enhance their absorption and maintain adequate drug plasma levels; however, strict adherence to Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) dosing specifications may not always be clinically indicated (see Table 14.2). This is illustrated by contradictions in licensing by different countries (see tenofovir in Table 14.2). For further advice, assistance should be sought from a specialist pharmacist.

| Dosing specifications as per electronic Medicines Compendium; September 2007 (http://www.emc.medicines.org.uk) | |||||

| ARV | Effect of food | on C max | on AUC | Dosing specifications | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease inhibitors (PI) | |||||

| Tipranavir | Improves tolerability of RTV side effects | Unknown—awaiting testing | With food | Requires refrigeration | |

| Darunavir | Similar results with all meals tested* | Overall bioavailability ↑30% | With food | *High fat, standard, protein drink, or croissant and coffee | |

| Indinavir | Light snack comparable to fasting High fat | 86% ↓ | 80% ↓ | Without food but with water. 1 h before or 2 h after a meal, or with low fat, light meal | Drink at least 1.5 L/day |

| Lopinavir (film-coated tablets) | High fat meal (872 kcal, 56% from fat) comparable to fasting | No significant change | No significant change | With or without food | |

| Lopinavir (soft capsule) | Moderate fat meal (500–682 kcal, 25% fat) | 23% ↑ | 48% ↑ | With food to enhance bioavailability and minimise variability | |

| High fat meal (872 kcal, 55% fat) | 43% ↑ | 96% ↑ | |||

| Saquinavir | Increases absorption. Meal (1000 kcal, 46 g fat) | 70% ↑ | 70% ↑ | At the same time as ritonavir and with/after food | Absolute bioavailability is 4% due to poor absorption |

| Atazanavir | Minimizes variability | Reduces the coefficient of variation by approx 1/2 | With food | ||

| Fosamprenavir | No effect | With or without food | |||

| Ritonavir | Increases bioavailability | ‘Ingestion with food results in higher drug exposure than fasted’ | With food | Requires refrigeration. Used (at low dose) to boost drug levels of all PIs above | |

| Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors | |||||

| Tenofovir | Light meal—no effect. High fat meal (1000 kcal, 50% fat) | 14% ↑ | 40% ↑ | With food | Bioavailability is 25% when fasted. No recommendation for administration in USA. |

| Etravirine (TMC125) | High fat meal or snack, or standard meal | ↑ | ↑ 50%↓ fasting | With food | Low fat, high fibre meal comparable to fasting |

| Nevirapine | No effect | With or without food | |||

| Rilpivirine (TMC278) | Normal meal | 71% ↑ | 45%↑ | With food | |

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) | |||||

| Zidovudine | With or without food | With food to prevent nausea | |||

| Lamivudine | Delays time to C max | 47% ↓ | No effect | With or without food | |

| Emtricitabine | High fat meal | No effect | With or without food | ||

| Abacavir | Delays absorption | ↓ | No effect | With or without food | |

| Stavudine | Prolongs time at C max High fat meal | ↓ | No effect | On an empty stomach. At least 1 h before meals. | No clinical significance—can be taken with food |

| Didanosine enteric coated | Reduces drug absorption 1 h before food | 15% ↓ | 24% ↓ | On an empty stomach, at least 2 h before/after a meal, with at least 100 mL water | |

| Light meal (373 kcal) | 22% ↓ | 27% ↓ | |||

| High fat meal (757 kcal) | 46% ↓ | 19% ↓ | |||

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) | |||||

| Efavirenz | High fat meal | 79% ↑ | 28% ↑ | On an empty stomach preferably at bedtime—improve tolerability of nervous system effects | Only necessary to avoid fat if experience side effects |

| Normal meal | 17% ↑ | ||||

| Entry inhibitors | |||||

| Enfuvirtide | No effect | By subcutaneous injection | |||

| Maraviroc | High fat meal | ↓ 33% ↓ 33% Not tested in fasting state | With or without food | Efficacy and safety studies had no food restrictions | |

| Integrase inhibitor | |||||

| Raltegravir | Moderate fat meal | 5%↑ 13%↑ | With or without food | ||

2. Short-term side effects need managing.

General nonspecific side effects, such as nausea, fatigue and rash, are expected in the first 6–8 weeks of starting HAART so patients should be prepared for this and potential solutions that will enable them to persevere with the drugs until the side effects subside should be provided.

Other side effects tend to be drug-specific and require individual management. For example, most of the PIs list diarrhoea as a side effect that can usually be managed with loperamide before considering switching to another ARV. If drug options are limited, adverse effects may require managing using alternative methods such as supplementation with ispaghula fibre, calcium carbonate, 22 or l-glutamine. 18

3. Long-term side effects, such as metabolic complications, require preventing, monitoring and treating.

The story of lipodystrophy

Early days

Two studies published in 1998 defined a paradigm shift in HIV management. Firstly the success of HAART was reported with a dramatic decline in HIV-related mortality. Secondly, the long-term side effects of HAART began to emerge with case reports of ‘Crix belly’, ‘buffalo hump’ (Figure 14.4a) and ‘gynecomastia’, detailing accumulation of visceral fat in the abdomen, upper back and breast, respectively. 23 Concurrently patients complained of sunken cheeks, and ‘stick’ limbs with prominent veins due to loss of surrounding subcutaneous fat from face, buttocks and limbs (Figure 14.4). 23 This apparent fat redistribution coincided with metabolic changes and was termed lipodystrophy syndrome. Components included in this LD syndrome were the SAT loss of lipoatrophy (LA), the VAT gain of fat accumulation (FA), dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance (IR) and osteopenia. New manifestations continue to be reported such as fat accumulation in the axilla regions and pubic lipoma, resulting in a rather fluid characterisation of LD.

|

| Figure 14.4 • Reproduced from Dolin et al (eds), Aids Therapy, 3rd edn. Published by Elsevier Inc, 2008, with permission. |

Defining lipodystrophy

Investigating the aetiology of LD proved difficult, with lack of consensus and varying definitions, so a group of experts produced a clinical case definition to provide an objective method for reporting and comparing different studies. It was based on the underlying assumption that all the metabolic abnormalities were part of a single syndrome. 24 This assumption was based on early epidemiological studies suggesting that LA occurred in tandem with FA, due to methodological reliance on self-defined LD to assess predictive values.

Multivariate analysis of large epidemiological studies elucidated multiple risk factors, suggesting complex interactions between host, disease and drug factors:

• Host (age, sex, race, BMI, diet, exercise, hormonal, genetic disposition);

• Disease (duration of infection, severity of immune depletion, magnitude of immune reconstitution); and

• Therapy (specific drugs, duration of therapy, cytokine activation, mitochondrial dysfunction).

Subsequent epidemiological exploration began to suggest that the visceral and subcutaneous fat compartments were distinct, with different pathogenic pathways affected independently by the different factors. 25

LD as two separate issues—lipoatrophy and fat accumulation

Meanwhile, multicentre, cross-sectional trials set up to determine associations by statistical means examined all the factors of fat change separately and found that the accumulation of visceral fat and depletion of subcutaneous fat were separate entities. The Fat Redistribution and Metabolism (FRAM) study, with a cohort of 1183 HIV-infected subjects and 297 controls, demonstrated that lipoatrophy was associated with HIV infection in both men and women, but VAT was lower in HIV-infected men than in control men and higher in HIV-infected women than in control women. 6 Importantly, there was no statistical association between the amount of subcutaneous fat and visceral fat in either men or women. Similar results were obtained in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. 26 Thus LA is an HIV phenomenon, whereas FA is not. Another previously thought HIV-specific symptom, buffalo humps, were discovered at a higher incidence in uninfected controls (FRAM study) and strongly associated with insulin resistance (i.e. metabolic syndrome) rather than LA. 27

Is fat accumulation masquerading as metabolic syndrome?

Having ascertained two distinct entities of LD, the defining features of FA were examined and found to be similar to those of the metabolic syndrome (MS). When the earlier definition of LD was validated, 24 it was found to produce results similar to scoring for metabolic syndrome (as defined by the International Diabetes Foundation 2005—see Chapter 17), indicating that the metabolic abnormalities may have been falsely attributed to the development of LD rather than MS.

Is metabolic syndrome related to HIV?

Metabolic syndrome was assumed to be more common in people with HIV infection when increased rates of individual components of MS (diabetes, dyslipidaemia, central obesity, hypertension) began to be reported in the HAART era compared to the previous pre-HAART era. However, when prospective cohorts of infected and uninfected were compared and matched for age, sex, race and smoking status the prevalence rates of MS were found to be similar (around 25%), with no link between MS and either HIV infection or ARV use. 28,29 A possible explanation is that the persistent increases in trunk fat (leading to the associated issues of obesity and metabolic syndrome) represent a generalised ‘return-to-health’ phenomenon associated with viral suppression and immune reconstitution. Despite this apparent normal occurrence, the contributing factors of MS were found to be different; driven by low high density lipoprotein (HDL) and high triglycerides (TG) in those with HIV infection (synonymous with the effects of HIV infection and ARVs, respectively28,29) rather than increased weight and waist circumference in the general population. This incongruity highlights the potential importance of identifying and addressing MS risk factors, particularly as MS has been associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in HIV.

Causes of lipoatrophy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree