It is impossible to say how many of the women really had true diabetes mellitus in a severe form, as the data are lacking, but it is fairly certain that the outlook of the diabetic patient who becomes pregnant is a bad one. The introduction of insulin in the treatment of diabetes has altered the prospects of the diabetic patient, and it is important to consider how much the outlook of the pregnant woman has been altered. I have had the opportunity of watching one woman who had been treated with insulin before conception and has given birth to a healthy child.

The patient, aged 34, had already had one child. She was quite well until she had a sudden onset of thirst, and became very irritable, in October 1922. The sugar was discovered by Dr Philps about fourteen days after the onset of the symptoms. She was dieted by removal of the carbohydrates of the diet, but not very drastically, and she also did not adhere closely to the prescribed diet. I first saw her with Dr Philps in June 1923, as she had become very thin and weak. She then looked ill, and had obviously lost a great deal of weight. She was very constipated, and the abdomen was moving rather deeply with respiration, as though she was approaching coma. The knee-jerks were active, and there was no other sign of disease. The urine contained a great deal of sugar,and gave a brisk reaction for aceto-acetic acid. The blood sugar was not estimated then, as the diagnosis was not in doubt.”

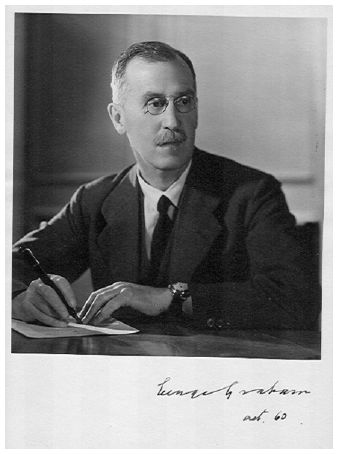

Fig. 4.2 Dr George Graham: 1882–1971. Consulting Physician, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. He was one of the early physician biochemists, and the first to describe renal glycosuria. He was the last important UK link with the preinsulin era, remembered for his “ladder diet” of gradually increasing carbohydrate intake. (Reproduced with permission of St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives.)

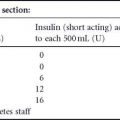

This patient must have been one of the very first to have been treated with insulin in London, in June 1923. Although aged 34, the presence of aceto-acetic acid in the urine (identified by the old ferric perchloride test, which was less sensitive but easier than the nitroprusside test for acetone), and extreme weight loss in spite of poor dietary adherence indicate what we now term Type 1 diabetes. Dr Graham continued to use the severe dietary restriction which was all that was possible before insulin – his 1350 calorie diet, giving 5% energy as carbohydrate and 78% as fat, would not please present day dietitians, but it certainly worked in the short term. After 2 months he allowed a very cautious increase to 1500 calories. The small dose of insulin by present day standards (10 U short-acting insulin once a day) clearly improved her general health and strength, but the energy restriction may have been of more benefit in achieving his aim of “resting” the islets of Langerhans – there has been some renewal of interest in this concept recently.

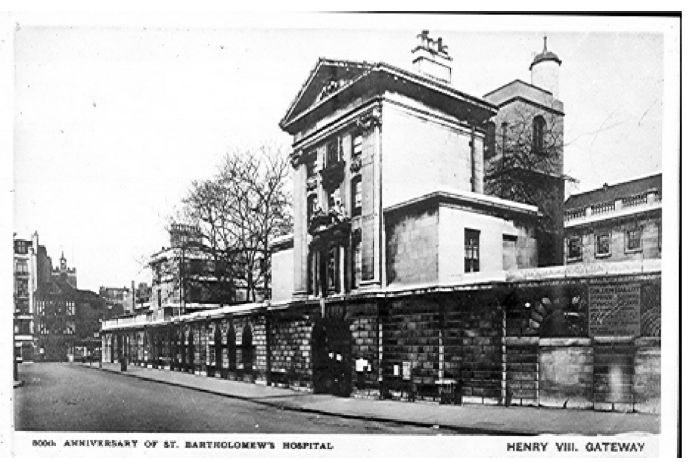

Fig. 4.3 St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. The King Henry VIII gateway. (Reproduced with permission of St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives.)

“She was treated drastically with two starvation days, and five units of insulin on the first day. The urine was sugar-free after the second day, and the diet was gradually increased up to: protein 57 grm, fat 118 grm, sugar 16 grm, caloric value 1,360; calories per kilo 30. The blood sugar one week later was 0.11 per cent [6.1mmol/L; 110 mg/dL], and insulin administration, 10 units, was begun on the tenth day in order to give the islets of Langerhans as little work to do as possible. She improved greatly in health and strength during the next eight weeks while she was in bed, and gained 1 lb in weight in spite of the low caloric value of the diet. The blood sugar remained between 0.1 per cent [5.5mmol/l; 100mg/dL] and 0.12 per cent [6.6mmol/L, 120mg/dL], and the diet was increased to protein 70grm, fat 126grm, sugar 21grm, calories 1500 on August 29.”

Although she was “in bed” for the first 8 weeks of insulin treatment – probably at home rather than in hospital – this did not interfere with conception, which must have occurred very soon after starting the new drug. There would not have been any package insert or National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline regarding the unknown effects of this new therapy on pregnancy, but doctor, patient, and husband must all have been pleased with the outcome.

“Sometime about the third week after the insulin treatment was begun the patient became pregnant in spite of precautions. On August 29, 1923, she had missed two menstrual periods, but she seemed very well, and the blood sugar was normal. I regret now that I did not test out her sugar tolerance with a dose of 50grm of dextrose for the sake of comparison with her present condition and with that of other patients. Until December 10, 1923, she kept very well, and was then six months pregnant, and was 9lb heavier than in August. There did not seem any indication to interfere, especially as the parents wished for another child. Unfortunately she was developing a severe coryza that afternoon, and the blood sugar was 0.19 per cent [10.6 mmol/L; 190mg/dL]. She was told to stay in bed, and to increase the dose of insulin so long as she was ill, but for various domestic reasons she did not do so. The illness, which was perhaps influenza, made her quite ill, and by January 4, 1924, she had lost a good deal of weight and felt very weak. The blood sugar was 0.24 per cent [13.3mmol/L; 240mg/dL] although she had had 15 units of insulin six hours before the blood was collected.”

As so often happens, the pregnancy may have been unplanned from Dr Graham’ s point of view, but the patient and her husband were clearly happy in spite of the medical opinion. When he saw her at 6 months of gestation she was developing some form of infection – this was not long after the severe pandemic of influenza throughout Europe, and he advised bed rest. But it was Christmas time, and she kept going somehow, but lost weight and became “quite ill”. Infection was the main cause of uncontrolled ketoacidosis in those early days of insulin therapy – we would increase the insulin dose more today, even if we still do not have effective antiviral chemotherapy.

“The question of terminating the pregnancy was considered in consultation with Dr. P. R. Bolus and Dr F. G. K. Philps, but it was decided not to do anything at that time as it was thought too dangerous while the diabetes was so severe. She was therefore kept in bed on a much reduced diet, and the insulin was increased to 15 units in the morning and 5 at night. On this regime she ceased to pass sugar in the urine, but the fasting blood sugar was 0.2 per cent [11.1mmol/L; 200mg/dL] on January 12. On January 26 the blood sugar had fallen to 0.14 per cent [7.7mmol/L; 140mg/dL], and the dose of insulin was reduced to 10 units in the morning and 5 at night. The diet was kept constant at protein 57grm, fat 117grm, sugar 16grm, caloric value 1,360. This is the same diet she was having in July 1923, and at that time she was only having 10 units of insulin in the day and the blood sugar was normal. The insulin requirements of the patient had therefore increased by 5 units, but whether this was the result of the pregnancy or only of the influenza from which she was suffering cannot be stated with any certainty. As she was feeling better but still weak the diet was increased to protein 74grm, fat 138grm, sugar 23 grm, caloric value 1,600.”

Termination of the pregnancy at 7 months was a drastic option, and his two colleagues must have been as optimistic about the pregnancy as they were afraid of the diabetes and the dreaded ketoacidosis. Cesarean section, or even premature delivery, was not possible, especially in an uncontrolled diabetic patient. Most of the maternal deaths in diabetes in pregnancy were due to the diabetes rather than obstetric problems. The small increase in the insulin dose was probably sufficient in view of the severely restricted food intake. Perhaps the nutritional deficiency helped to prevent fetal macrosomia in the last weeks of pregnancy.

“Labour began on March 3, 1924, and was conducted by Dr Bolus. Scopolamine and morphia were given, and the labour terminated very easily. The child was quite healthy, and the patient was not unduly disturbed. During the first 10 days of the puerperium the diet was increased by 40oz of milk, and 15 extra units of insulin were given to look after the extra sugar – protein 114 grm, fat 174grm, sugar 65 grm, caloric value 2,250. The extra sugar was given with the object of having more sugar in the body in a form in which it could be used, so that the patient might be able to deal with any minor septic complications which might arise. Fortunately there were no complications at all.”

Fortune favours the brave, and all went well. He made no further comment on the baby, who was presumably of normal size and appearance. With the small doses of insulin there was little risk of hypoglycemia, which does not seem to have become a problem in diabetes in pregnancy for many years, until the desire for totally normal blood glucose as well as normal food intake necessitated more insulin. Various forms of long-acting insulins have probably exacerbated the tendency to hypoglycemia, both in early gestation and postpartum.

“The increase in the sugar caused her to excrete sugar again, as the insulin was not quite sufficient, but it was thought better to allow her to excrete sugar for a few days than to run any risk of overdosage, as the insulin requirements might have been much less as the result of the termination of the pregnancy. On the tenth day the milk was reduced to 4oz and the insulin to 18 units in the morning and 8 units at night. She made a good recovery and has felt very well and much stronger. On March 26, 1924, the blood sugar was 0.2 per cent [11.1mmol/L; 200mg/dL], although she was not passing any sugar, and as it was still at this figure on April 5, the milk was stopped altogether and the insulin increased by another 2 units to 28 units.”

The concept of allowing rather higher blood glucose immediately post delivery would still find favor today. It is not clear if the baby was breastfed, but this was probable in those days, at least initially. We would all like to know what happened in the future – this baby could now be 94 years old.

“On reviewing the case it is clear that the sugar tolerance has diminished considerably during the past ten months, but whether this is due to the pregnancy or to the influenza it is impossible to say. The prognosis in any case of true diabetes mellitus is affected in various ways, and one of the most serious is the incidence of infections of any kind. If, therefore, a diabetic woman becomes pregnant, it seems probable that she will be liable to many more dangers than before, even if the strain of the pregnancy does not cause any ill effects. The special danger is that of sepsis during parturition, as the patient’ s resistance to this will probably be very small. Although the present case shows that a pregnancy can be carried through successfully on a diet of low caloric value with the help of insulin, it seems to me that the patient runs a grave risk of the diabetes being made considerably worse.”

Doctors are always inclined to dwell on the risks – his fear of long-term exacerbation of diabetes by pregnancy has not been confirmed. The reduction of the risk of infection may have been just as important as the use of insulin.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF DIABETES IN PREGNANCY

The most comprehensive assessment of the historical publications on diabetes and pregnancy is by Mestman, an endocrinologist and obstetric physician who has worked in Southern California since 1960.11 Following the paper by Matthews Duncan in 1882,2 Mestman indicates the major change which followed was the introduction of insulin, allowing a woman with diabetes to carry a full-term pregnancy and deliver a healthy infant. He documents the dramatic reduction in maternal mortality, and the more modest improvement in perinatal mortality and morbidity. It was not until the recognition of the need for a team approach, from obstetrician, diabetologist, and pediatrician, that the fetal outcome improved.12 The gradual introduction of obstetric (or maternal/fetal medicine) tests to assess placental function,13 fetal well-being,14 and fetal lung maturity15 resulted in the reduction of three of the causes of fetal loss – sudden intrauterine death, neonatal death, and birth trauma due to macrosomia. Not all of these tests have stood the test of time, but the academic interest which they generated was largely responsible for the recognition of diabetes in pregnancy as a high-risk process, requiring special supervision not available except in centers of excellence. This left congenital fetal abnormalities as the residual problem, even in these centers. Basic animal and human research then showed that poor glycemic control at the time of conception and soon after was a major cause of both congenital abnormalities and spontaneous abortion.16 However, the provision of this degree of detailed care for all diabetic mothers at a community level has been more difficult to achieve, and a number of national surveys have shown deficiencies in many aspects of this healthcare provision.17

Definition of gestational diabetes

Another reason for differing results has been the actual definition of “gestational diabetes mellitus” that has been adopted. The early reports concentrated on a specific pregnancy-induced problem, which was assumed not to have been present before, and shown not to be present after the pregnancy. The most controversial topic in the early days was the significance of the finding of sugars of various types in the urine, and the role of this finding in the diagnosis of asymptomatic diabetes. J. W. Williams in Baltimore, USA came to a number of conclusions in a review of the literature up to 1909.3 His own studies showed that between 1 and 3 g/L of sugar in the urine was most likely physiologic, but more than this suggested diabetes, particularly early in pregnancy or if symptoms were present. In 1926 Lambie in Edinburgh reviewed the problems associated with glycosuria and acetonuria in pregnancy, and discussed the details of a 50-g oral glucose tolerance test with calculations of what he termed the ketogenic–antiketogenic balance.18 Perhaps the earliest report of glucose “intolerance” in pregnancy, quoted by Lambie, was in the thesis in Paris by Brocard in 1898, who found glycosuria 2 hours after ingesting 50 g of glucose in 50% of pregnant compared to 11% of non-pregnant women. Ten years after the discovery of insulin, a complete literature review was published by Eric Skipper of 136 pregnancies in 118 diabetic women, and of a further 37 under his own care at the London Hospital.19 Among other important observations, he drew attention to the high fetal mortality (39%) in women where the apparent onset of the diabetes was during the pregnancy, almost as high as that with onset before pregnancy (46%). Priscilla White in 1949 (Fig. 4.4) summarized her long experience at the Joslin Clinic in Boston in a classic paper which established what became known as the “White Classification”.20 White class A indicated women with “a glucose tolerance test which deviates but slightly from the normal” either before or during the pregnancy, who were treated with diet alone, and was never synonymous with gestational diabetes, which was uncommon in the established diabetic population of the Joslin Clinic. Subsequently, J. W. Hare revised the classification to separate gestational diabetes from the alphabetic list,5 but the overall classification has now outlived its usefulness.

Screening for hyperglycemia in pregnancy

Gradually antenatal screening for unrecognized hyperglycemia in pregnancy became established, although without an unequivocal evidence base, and the screening processes used were different in different countries.21,22 In historical terms, different screening and diagnostic procedures, even within the same country, as well as the increasing incidence of diabetes in the background populations and the rapidly altering demographic trends in human reproduction, have resulted in considerable variation in the reported prevalence. In Scandinavia the outcome of pregnancy in indigenous women has for many years been better than in other parts of Europe, and these differences are also seen in the diabetic populations. The increasing prevalence of obesity and the immigration of women from ethnically different populations have altered these findings, and recent studies are more similar to the North American experience.

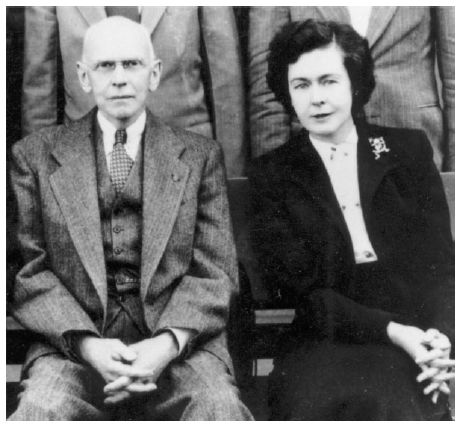

Fig. 4.4 Dr Priscilla White, with Dr Eliot Joslin, at the Joslin Clinic, Boston. (Reproduced with permission from the Joslin Archives, Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, USA.)