Hip Disarticulation and Creating an Above-Knee Amputation Stump after Hip Disarticulation

Daria Brooks Terrell

Amir Sternheim

BACKGROUND

Hip disarticulation is an amputation of the lower extremity through the hip joint capsule. Although most tumors of the lower extremities are amenable to limb-sparing techniques, some tumors of the femur and thigh are so extensive that hip disarticulation is needed for adequate tumor resection.5,6,12

Disarticulation of the hip for malignant tumors is a rare operation, but it is still needed instead of an above-knee amputation if the tumor cannot be resected using a limbsalvage procedure due to proximal transosseous skip metastases, pathologic fractures, extensive diaphyseal extension, and large adjacent soft tissue masses combined with a poor response to chemotherapy.1,11,14

With advances in prosthetic design, patients can ambulate with a prosthesis despite the larger energy expenditure needed to ambulate after a hip disarticulation compared to more distal amputations. Even without prosthetic use, most patients are very successful in ambulating and carrying out daily activities.

Performing a hip disarticulation may be more preferable in some cases instead of leaving a patient with a very short above-knee amputation stump site, which can make prosthesis fitting difficult.

Because functional outcome after hip disarticulation is problematic, Jain et al4 published their results of 80 hip disarticulations. Function on the whole was poor, with only one surviving patient regularly using an artificial limb. Patients after hip disarticulation are left without a leg and without a fulcrum to move an artificial limb. They are likely to suffer loss of self-esteem as well as loss of function and mobility, and they may well suffer from phantom pains.

The energy expenditure during mobility after an amputation is much greater than that without an amputation and increases as the amputation level becomes more proximal.13 The energy expenditure after a hip disarticulation is reported to be 82% greater than that required by a nonamputee.2,3,10 In comparison, the energy expenditure after a long below-knee amputation is only about 10% more than that required by a nonamputee. When a patient with a hip disarticulation attempts to use a prosthesis, the energy requirements can then be as much as twice that of a normal ambulator. Those who cannot overcome these significant energy requirements must adapt to the use of crutches, canes, or a wheelchair. Given these factors, any intervention that can reduce the energy expenditures required of amputees might increase their likelihood of mobility and improve their overall quality of life.2,3,5,10

By preserving the soft tissues of the proximal thigh when amputating the leg at the level of the hip joint, it is possible to reconstruct a functional proximal thigh stump with a proximal femur prosthesis. This requires that the proximal soft tissues of the thigh are without tumor invasion, which is an uncommon situation. This is a rare procedure with only few indications, but it remains an important option due to its benefits over a standard hip disarticulation.

Preserving hip function is the main advantage of stump prosthesis over hip disarticulation. The main disadvantages of a hip disarticulation are its unappealing appearance; the discomfort of the basket-shaped prosthetic socket, which incorporates nearly half of the pelvis; and the 82% increase in energy consumption required for walking compared with that in a normal person.10

The stump prosthesis provides a lever arm for hip joint motion. This dramatically lowers the energy consumption of ambulating with a prosthetic limb and thus increases the likelihood of prosthetic use.9

The first attempt to improve the functional status of patients requiring hip disarticulation for malignant bone tumors was published in 1979.8

ANATOMY

The hip joint region is supplied by several major arteries. Familiarity with these structures can minimize intraoperative bleeding if they can be identified and ligated as needed. These arteries include the profunda artery, the medial and lateral circumflex arteries, and the obturator and superior and inferior gluteal arteries.

The tensor fascia lata, gluteus maximus, and iliotibial band form an outer muscular envelope around the hip, and at least one of these structures usually needs to be split to gain access to the hip.

The femoral triangle must be identified to access the main neurovascular structures encountered in this procedure. The femoral triangle is bordered superiorly by the inguinal ligament, laterally by the sartorius muscle, and medially by the adductor longus muscle.

Hip disarticulation involves amputation through the hip joint capsule. This strong fibrous layer covers the anterior hip to the intertrochanteric line but leaves most of the femoral neck exposed posteriorly.

Tumors can often extend to the ischiorectal fossa; this should be determined preoperatively by examining computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The ischiorectal fossa is an area bounded medially by the sphincter ani externus and anal fascia, laterally by the tuberosity of the ischium and obturator fascia, anteriorly by the fascia covering the transversus perinei

superficialis, and posteriorly by the gluteus maximus and sacrotuberous ligament. Assessment for tumor extension to this area is particularly important in planning the flaps that will be used.

INDICATIONS

Proximal tumors not extending above the midthigh

Femoral diaphyseal tumors with proximal intramedullary extension

Soft tissue sarcomas of the thigh with extension to the femur or neurovascular structures

Unresectable local recurrences, particularly after radiation therapy has been used

Pathologic fractures that are not responsive to induction chemotherapy and immobilization

Palliation of extensive tumors

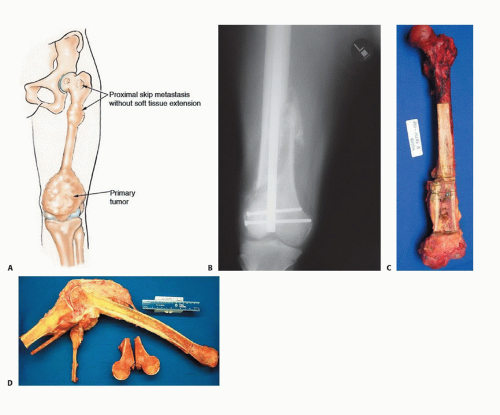

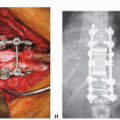

Indications for stump prosthesis reconstructive surgery after hip disarticulation are as follows (FIG 1):

Skip metastasis to proximal femur from a primary distal femur osteosarcoma

Inability to achieve safe osseous margins with a typical wide resection or above-knee amputation due to tumor extension (the most common indication)

Tumor contamination of the proximal medullary canal after pathologic fracture due to tumor in the distal femur and retrograde intramedullary fixation.

A prerequisite for the operation is uncontaminated soft tissues around the hip, retrogluteal region, and proximal thigh.

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

Plain Radiography

Hip and pelvic imaging to rule out pelvic involvement

Radiographic analysis of the entire femur

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

CT is useful in showing the effect of the tumor on the structural integrity of the bone. It may also show extension into the soft tissues, especially in the ischiorectal fossa, hip joint, and groin.

MRI shows the intraosseous spread of the tumor within the marrow and therefore is helpful in determining the level of amputation and the appropriateness of the hip disarticulation.

Bone Scanning

A bone scan is helpful in evaluating the bony involvement of the femur, pelvis, and acetabulum. It will also show any incidence of skip metastases.

Acetabular involvement is a contraindication to doing a hip disarticulation.

Angiography and Other Studies

Angiography can help identify the external iliac, common femoral, and profundus arteries when preparing for surgery.

Biopsy

A biopsy is warranted before most amputations. Given the potential functional limitations and prosthetic needs of a hip disarticulation, a biopsy is definitely recommended before performing a hip disarticulation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Lymph node involvement should be assessed before proceeding with a hip disarticulation. Lymph node involvement is a relative contraindication to performing a hip disarticulation unless the procedure is done for palliation.

Hip disarticulations are often required after poor chemotherapy response or tumor aggressiveness. These situations increase the likelihood for close surgical margins, which can lead to local recurrences.

All radiographic studies must be reviewed to ensure that there is no suggestion of tumor proximal to the lesser tuberosity. This would increase the risk of having positive or close margins.

The development of the flaps is critical for optimal wound closure and healing. It is not uncommon to make flaps of unusual shape in performing a hip disarticulation for tumor of the middle or distal femur or thigh. Previous scars, radiated fields, and the presence of a tumor mass all determine the best skin to be used. If possible, fasciocutaneous flaps should be constructed to promote would healing.

Optimizing the patient’s overall health and nutritional status preoperatively is essential in promoting wound healing and decreasing perioperative complications. When planning for an amputation stump after disarticulation:

Arterial blood supply to the soft tissues must be preserved. The superficial femoral artery should be ligated within the sartorial canal as distally as oncologically possible.

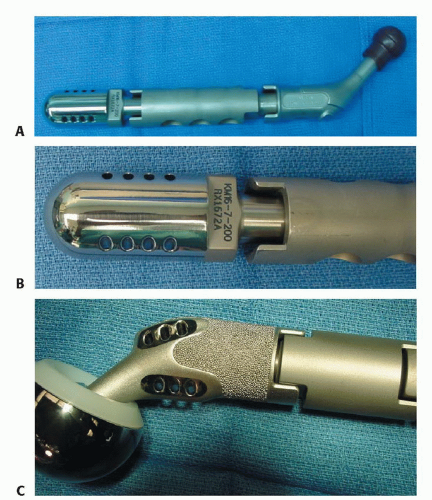

The prosthesis must be secured to the hip capsule to avoid dislocation aggravated by gravity pulling on the prosthesis. This requires capsular reconstruction and reinforcement.

Modular prosthetic design allows use of a large bipolar cup, modular body length with porous coating to aid in soft tissue ingrowth, and a distal rounded tip designed to avoid tissue penetration with distal muscle fixation holes (FIG 2).

Muscle groups of the thigh must be connected distally to the prosthesis with tension balanced properly to avoid the excessively strong pull of the hip flexors and abductors.

Sufficient soft tissue coverage of all the prosthesis, and specifically its distal part, is critical.

Phantom pain and stump pain should be addressed initially by placing an epineural catheter in the transected sciatic nerve and using multimodal analgesia.

Preoperative Planning

MRI and CT are done to determine the extent of the tumor in the proximal femur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree