Lesion

Relative risk

Usual ductal hyperplasia

2.0

Subareolar papilloma

2.0

Radial scar

1.8

Multiple papillomas

3.1

Papilloma with atypia

5.1

Radial scar with atypia

5.8

Papillomatosis with atypia

7.0

LCIS

8–10

Benign Proliferative Lesions (Relative Risk 1.5–3×)

Women who have a clinical symptom or imaging abnormality resulting in biopsy have an increased risk of developing breast cancer in the future about twice that of asymptomatic women with normal imaging and no risk factors [3]. In this chapter, we will discuss the benign proliferative lesions that increase a woman’s risk for developing breast cancer.

Usual Ductal Hyperplasia

Usual hyperplasia is often seen on pathology reports after biopsy for imaging abnormalities or after excisional biopsy of a mass or thickening. In of itself, there is no direct imaging corollary. It is often found in association with sclerosing adenosis, apocrine metaplasia, and psuedoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia [4].

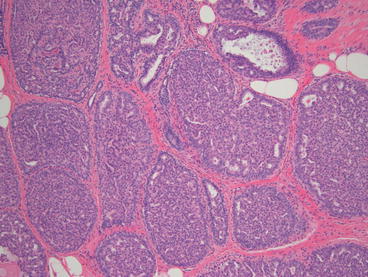

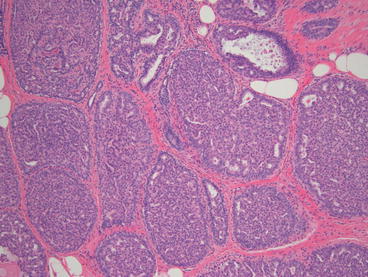

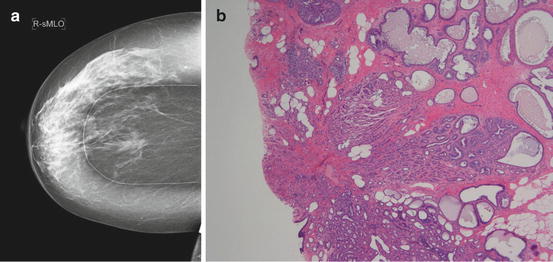

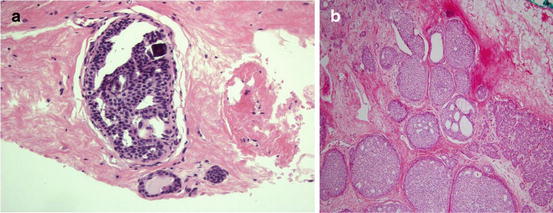

Ductal hyperplasia is defined as the ducts or lobular units having more than two cell layers of thickness above the basement membrane. Hyperplasia may be further subdivided by the number of cell layers present. Mild and moderate hyperplasia has a few identifiable cell layers. The transition to severe or florid hyperplasia is not well defined. As the level of hyperplasia increases, cellularity increases such that the entire lumen may be filled with cells. The cells have reduced cytoplasmic volume compared to normal ductal cells, although mitotic figure are rare [5] (see Fig. 14.1).

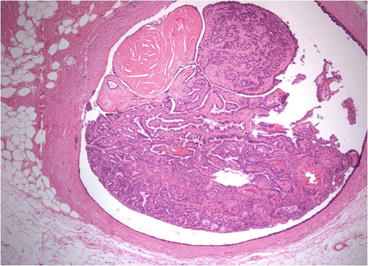

Fig. 14.1

Histologic appearance of usual ductal hyperplasia (10×)

While ductal hyperplasia is considered a proliferative lesion, the cells are not associated with atypia, and therefore, are not premalignant. The risk of subsequent cancer, for usual hyperplasia without atypia varies from 1 to 8.6 % in the literature. The lesion is generally considered to double a patient’s risk. The relative risk of this lesion is dependent on the degree of hyperplasia and other risk factors, such as family history [6].

Identification of this incidental finding on core needle biopsy or excision does not warrant further intervention. Patients found to have ductal hyperplasia are encouraged to continue annual screening mammography and are referred for high risk evaluation only if other patient risk factors are present.

Solitary Papilloma

Symptomatic papillomas are often identified on clinical examination of a patient presenting with nipple discharge. In fact, a papilloma is the most common cause of pathologic nipple discharge [7, 8]. Central papillomas more often present with discharge (86 %) compared to peripheral papillomas (29 %) [9].

Ultrasound imaging of central papillomas can identify a hypoechoic mass within a dilated duct. Peripheral papillomas, which are usually asymptomatic, are often larger and are found on screening imaging studies. They may manifest in imaging as calcifications, nodules, or masses. They may also be multiple and form a mass like effect on clinical examination [10].

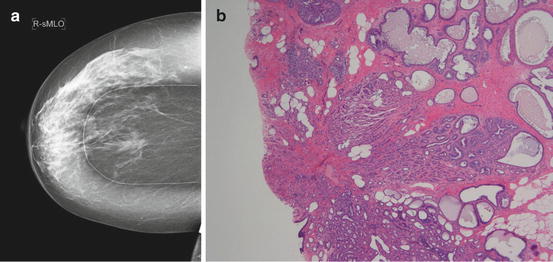

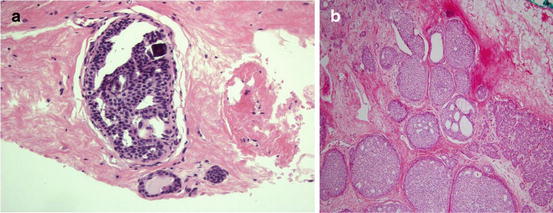

Papillary lesions are proliferative ductal lesions with a fibroepithelial core and are often described as “frond” like. They range in size from a few millimeters to a centimeter or more. Evidence of necrosis and or hemorrhage is common. Fragmented specimens obtained by core needles may be difficult for pathologists to interpret [11]. The concern with core needle biopsy for diagnosis of a papilloma is the potential of missing a well differentiated papillary carcinoma [12]. Excisional biopsy provides the pathologists with the entire lesion which is helpful in making the diagnosis (see Fig. 14.2).

Fig. 14.2

Histologic appearance of excised papilloma

The excisional upgrade rate of a core biopsy diagnosed benign papillary lesion to atypia or carcinoma is widely varied. Large vacuum assisted core biopsies that remove more of the visible lesion have lower upgrade rates. Without atypia in the core specimen, the upgrade rate to malignancy is reported to be from 5 to 25 %. Peripheral lesions are more often found to harbor malignancy (rates up to 30 %) than central lesions. Subareolar papillomas have less than a 10 % risk of associated malignancy on excision [13]. The risk of malignancy in patients with a papilloma, increases with patient age, palpability, abnormal imaging, and peripheral location [14].

The risk of in situ or invasive carcinoma upon excision with an atypical papillary lesion diagnosed by core biopsy is reported as high as 29 % [15]. Another study reviewed 345 patients with intraductal papilloma (IDP) on core biopsy. Among those patients with a benign IDP who subsequently underwent a surgical biopsy, 14 % upgraded to atypical ductal hyperplasia while 10.5 % upgraded to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). If the core biopsy also showed atypia, 22.2 % upgraded to DCIS [16].

There is literature to support imaging follow up for papillary lesions that are concordant when the entire imaging abnormality has been removed [12]. This should be institution dependent based on upgrade rates and size of needle used for biopsy. In general, symptomatic papillomas identified by clinical examination and peripheral papillomas identified by imaging studies, should be surgically removed to avoid the risk of pathologic upgrade to malignancy.

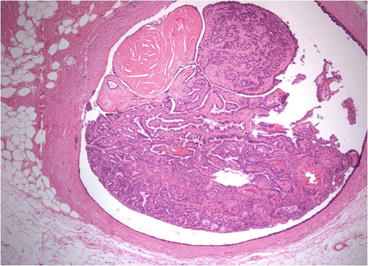

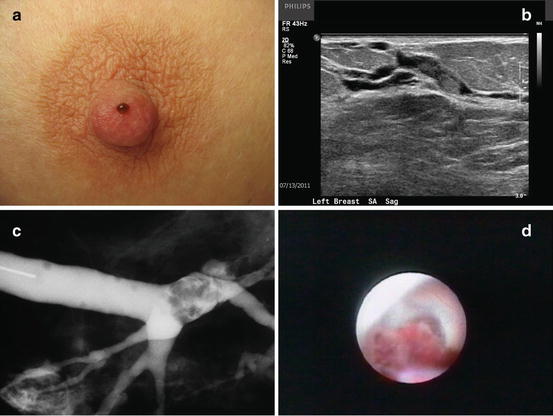

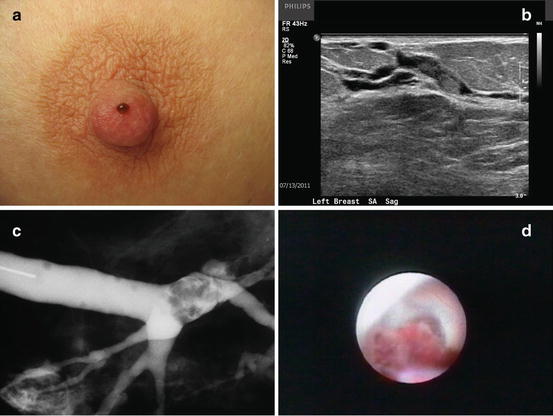

Symptomatic papillomas often present as pathologic nipple discharge (PND). These patients present with single duct, spontaneous, often bloody or serous discharge. If mammography shows no mass or calicfications, and the lesion is not palpable, the chance that this clinical presentation results in a diagnosis of malignancy is less than 10 %. Unfortunately, there is no test, including guaiac testing, smear cytology, ductography, or even ultrasound core biopsy, which can exclude malignancy. The combination of symptoms and risk of malignancy warrant excisional biopsy [17].

Directed-duct excision for patients with PND will yield a benign proliferative lesion up to 90 % of cases. The more directed the excision, the higher the yield. Ductogram with needle localization or ductoscopy-directed duct excision provide the highest proliferative lesion rates. Fibrocystic change and duct ectasia are not true causes of PND and a pathology report showing these non-proliferative findings likely mean that the lesion was not within the specimen or at least not identified by the pathologist. Proliferative lesion rates are much lower for nondirected central duct excisions. Recurrent discharge can be found in patients undergoing major duct excision without localization. Many of these lesions are within the nipple itself. Ductogram and ductoscopy can identify these lesions within the nipple. Second deeper lesions can be visualized and excised in 25 % of cases when using ductoscopy [8, 18].

An additional benefit of ductoscopy directed duct excision, besides direct visualization of the abnormality and detection of additional lesions, is removal of only the abnormal ductal system. This accomplishes lesion removal with lower volume of tissue resected.

It should be noted, if cannulation of the duct at the nipple is not possible, then major duct excision should be carried out because there is a higher chance of malignancy associated with duct obliteration [19] (see Fig. 14.3a–d).

Fig. 14.3

(a) Classic appearance of pathologic nipple discharge. (b) Ultrasound image of intraductal mass. (c) Ductogram showing an intraductal filling defect. (d) Mammary ductoscopy image of an intraductal papillary lesion

The risk of future development of malignancy is dependent on associated pathology, the number of papillomas, location of papilloma, and other risk factors. As evidenced by Lewis et al, the relative risk of breast cancer in a patient with a history of solitary papilloma without atypia is 2.04. In the same study, the relative risk increases to 5.11 if the patient had a solitary papilloma with associated atypia. However, the presence of a solitary papilloma with atypical hyperplasia does not significantly elevate the risk of future carcinoma above the level attributable to the atypical hyperplasia itself [14]. Like all breast lesions, the risk of malignancy is multifactorial and affected by other patient risk factors.

Radial Scar/Complex Sclerosing Lesions

Radial scars are most often identified incidentally upon biopsy for other abnormalities on physical examination or imaging studies. They may be found on imaging as a spiculated mass with or without microcalcifications. Radio graphically described as having the appearance of a “black star,” they may have linear radiating spicules with a radiolucent black center [20]. Incidence rates for radial scars are estimated to be from 0.6 to 0.9 per 1,000 women screened [21, 22]. A radial scar is considered a complex sclerosing lesion if the radial scar is greater than 1 cm in diameter [1] (see Fig. 14.4a).

Fig. 14.4

(a) Mammographic appearance of a radial scar with linear radiating spicules. (b) Histologic appearance of a radial scar

On gross pathology, a tumor with a retracted center may be seen, mimicking a carcinoma. These lesions, microscopically, have a central fibroelastic core containing entrapped glandular elements and ducts that radiate from the lesions center. The periphery of the lesion appears to be drawn inward toward the central core. Epithelial elements entrapped within the fibrous stroma may simulate an invasive carcinoma [23] (see Fig. 14.4b).

Despite their ominous appearance on imaging and pathology, these lesions are benign and no further treatment is needed for benign radial scars found on excisional biopsy. Radiologic–pathologic concordance is often difficult to establish when the biopsy is performed for a mammographically detected lesion. Due to the frequently discordant nature of the pathology, radial scars are often excised on that basis alone. Linda, et al. found that the mammographic and sonographic features of the radial scar were not helpful in determining which harbored malignancy [24]. Because of the significant risk of upgrading to a more advanced histology, excision is usually recommended when a core biopsy demonstrates a radial scar or complex sclerosing lesion.

Pathologic upgrade rates upon surgical excision to a high risk lesion or carcinoma for radial scars without atypia on core biopsy range from 0 to 28 %. If they are found to harbor atypia on core biopsy, the range increases dramatically, from 28 to 44 % [25]. In these and other reviews, increasing age, postmenopausal status and increasing lesion size are suggested as risk factors for higher upgrade rates [26].

The relative risk of cancer developing in women with a previous radial scar is 1.8 without associated atypia. In those women with atypia, the relative risk increases to 5.8 [27]. As is the case with women diagnosed with papillomas, the risk of cancer development in patients with radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions is dependent on the risk potential of the associated histology, not the lesion itself.

Mucocele-Like Lesions

Initially described by Rosen in 1986, these lesions appear as mucin containing ducts or cysts that may discharge the mucin into the surrounding stroma. There are varying degrees of epithelial cells within the stroma, some completely acellular. Inflammatory cells may also be found. Mucinous or colloid carcinoma is in the differential when evaluating mucocele-like lesions (MLL) [28].

Mucocele-like lesions typically present as indeterminate calcifications on mammography. In a study from 2011, 27 of 44(61 %) patients presented with calcifications alone while an additional seven (16 %) had microcalcifications associated with a mass [29]. Others may present as a mass lesion on sonography or exam or incidentally upon biopsy for other reasons. Imaging characteristics have been described to differentiate benign from malignant MLL. The malignant MLL or those with associated atypia are more likely to have concerning microcalcifications or complex cystic structures [30].

Recent review from Carkaci reports the conversion from a MLL with atypia on core biopsy to DCIS upon excision in 3 of their 16 patients (19 %). None of their patients without atypia had DCIS upon excision [29]. Conversely, Liebmanns study found patients with a benign mucocele-like lesion on core needle biopsy, 25 % upgraded to an indraductal carcinoma when excised. In addition, those with associated atypia were found to harbor it 75 % of the time [31]. Although some authors advocate observation in those patients with complete removal of the imaging abnormality with the core biopsy procedure, concern for potential upgrading of the pathology as well as the misdiagnosis of a mucinous carcinoma is significant enough to warrant excision of mucocele-like lesions found on core biopsy [32, 33].

Mild Risk Lesions (Relative Risk 2–3×)

Papillomatosis (Epitheliosis)

These lesions are found either as a mammographic density or calcifications, and may present as pathologic nipple discharge. If multiple or large, papillomatosis can present as a palpable abnormality on examination. The majority of cases of multiple papillomas are found in the peripheral terminal ductal lobular units [13]. Papillomatosis is most consistent with micropapillary ductal hyperplasia rather than “multiple papillomas.” Gendler defines papillomatosis as at least five papillomas in the same quadrant, or in at least two consecutive pathology tissue blocks [34].

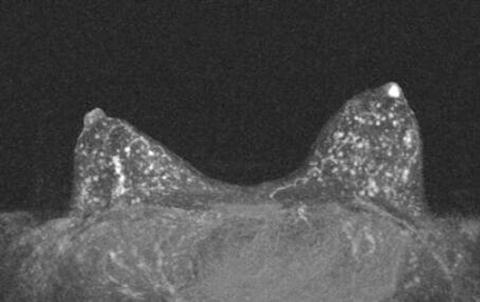

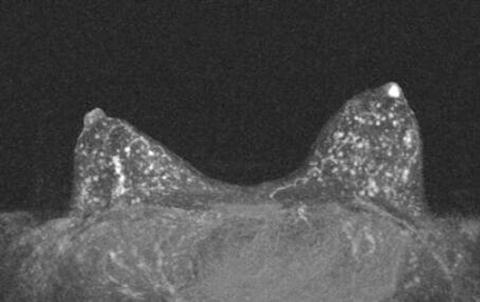

The use of MRI for preoperative planning for the extent of disease in papillomatosis is controversial because of the high sensitivity of MRI for papillary lesions. The problem is that it is difficult to distinguish papillomatosis from malignancy on MRI. A large portion of the breast may enhance which cannot be surgically removed without significant deformity. For this reason, many surgeons prefer to forgo MRI when the diagnosis is papillomatosis, concentrating on removing the portion of the lesion that is clinically symptomatic, or mammographically abnormal [35] (see Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

MRI findings of a patient with a negative mammogram and pathologic nipple discharge. She has diffuse papillomatosis which can be difficult to differentiate from malignancy on MRI

Papillomatosis is a mild to moderate risk lesion that differs both histologically and in its risk from solitary papilloma. It is at times not possible to completely excise, although the most mammographically evident or palpable portion should be removed to rule out associated malignancy. As with other proliferative lesions, the risk of subsequent malignancy is multifactorial and associated with other patient risk factors.

There is a higher risk of associated cancer (especially DCIS) with papillomatosis than with solitary papillomas. Ohuchi reported that 6/16 patients with peripheral papillomas originating in the terminal ductal lobular unit harbored carcinoma, whereas, none of the nine central papilloma patients had malignancy [13]. In the review of patients in the SEER database, it was demonstrated that the relative risk of cancer development in patients with multiple papillomas was 3.01 without atypia and 7.01 with atypia. This is in contrast to patients with solitary papillomas whose relative risk was 2.04 with and 5.11 without atypia [14].

Moderate Risk Lesions (Relative Risk 4–6×)

Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH)

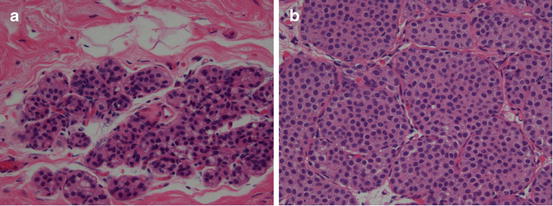

Like many of the other high risk lesions atypical ductal hyperplasia, ADH is found incidentally or upon biopsy of indeterminate or suspicious microcalcifications. One study found that 9 % rate of ADH for all of the stereotactic biopsies performed for BIRAD’s category 4 or higher mammographic abnormalities [36]. ADH is defined as an intraductal proliferation showing the features of low grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), but in less than two duct spaces or less than 2 mm in diameter [37]. The cells in ADH have distinct borders, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear enlargement, and irregular chromatin/nucleoli. The difference between ADH and DCIS is a measure of degrees, or magnitude of the cellular change. Therefore, there is significant intraobserver variability when making the diagnosis (see Fig. 14.6).

Fig. 14.6

ADH and DCIS are similar in characteristics but differ in the degree of abnormality present. (a) Histologic appearance of atypical ductal hyperplasia. (b) Histologic appearance of ductal carcinoma in situ

Because the diagnosis of ADH or DCIS is dependent on a multitude of factors, the upgrade rate to carcinoma upon excisional biopsy varies. As an example, when large bore vacuum assisted breast biopsy is used for diagnosis, upgrade rates can be as low as 10 % [38]. Not surprisingly, when using a 14 gauge needle, upgrade rates have been reported as high as 87 % [25]. The extent of ADH within the specimen, the type of microcalcifications biopsied, and the pattern of the ADH ,with micropapillary having a higher risk, have all been determined to play a role in increasing the upgrade rate [39].

Atypical ductal hyperplasia is associated with increased risk of developing future breast cancer with a relative risk (4.5–5×) or even higher if the patient is premenopausal or has a family history of breast cancer. The risk is for bilateral breast cancer which suggests that ADH may be a marker for breast cancer instead of a direct precursor [37].

Due to the risk of finding concomitant carcinoma in the specimens, and significant intraobserver variability of the diagnosis, excisional biopsy should be done for all patients with core biopsy diagnosed ADH. Upgrade rates vary in the literature and average around 25 %. They are never lower than 10 %, however, even when large bore vacuum-assisted biopsies are performed [40]. Once excision has been performed, patients diagnosed with ADH should be referred to a high risk screening program or assessed for other risk factors.

Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia

Much of the literature does not differentiate lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) from atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), but instead uses the term lobular neoplasia (LN) to encompass both entities. Although lobular neoplasia is often found incidentally with core needle biopsy or excisional biopsy of imaging abnormalities, it may be associated with microcalcifications or a mass on imaging [1]. More recently, two studies have found LN associated with microcalcifications in notable numbers of their reported core biopsies suggesting that it can be associated with imaging abnormalities [41, 42].

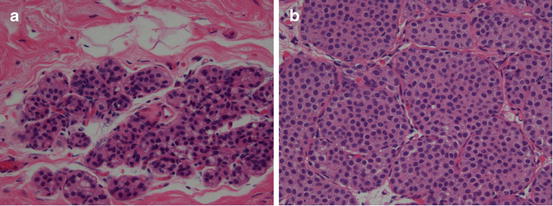

Both ALH and LCIS are a proliferative growth of a monotonous cell population. The difference lies in the percentage of the terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU) that is occupied by the cells. If the acini are greater than 50 % filled, it is considered LCIS. If less than 50 % filled, it is considered ALH [43]. Mitoses, calcifications and necrosis are rarely found in cases of ADH. As is the case with ADH and DCIS, there may be much observer variability in making the distinction (see Fig. 14.7).

Fig. 14.7

ALH and LCIS are similar in characteristics but differ in the degree of abnormality present. (a) Histologic appearance of atypical lobular hyperplasia. (b) Histologic appearance of lobular carcinoma in situ

Upgrade rates for ALH to cancer on core needle biopsy is generally lower than it is for ADH and LCIS. Many studies do not separate the lobular neoplasias. However, the upgrade rate for ALH is still substantial enough (over 10 % in most series) to warrant excisional biopsy for women with ALH found on core needle biopsy [39].

Multiple studies over the years have shown an increased risk of development of carcinoma (both ipsilateral and contralateral) in patients that have ALH. The subsequent ipsilateral cancer is most often at the site of the original lesion [44]. Relative risk for the development of carcinoma in a patient with the diagnosis of ALH is 4–5 times the general population. As with other high risk lesions, the patient’s individual risk factors influence their overall risk [43, 45].

High Risk Lesions (Relative Risk 8–10×)

Lobular Carcinoma In Situ

LCIS is found incidentally in benign breast biopsy specimens in .5–3.8 % of the cases reviewed [46]. In 2002, Li et al. reported the incidence of LCIS to be 3.19/100,000 person-years [47]. LCIS is often an incidental finding associated with histologic lesions identified in pathology reports for mammographic abnormalities or excisional breast biopsy for symptomatic breast disease.

If the acini of the TDLU are greater than 50 % filled, it is considered LCIS. As with the distinction between ADH and DCIS, there may be significant intraobserver variability in making the diagnosis. Histologically, LCIS often has neoplastic cells with scant cytoplasm and small, round, bland nuclei. The great majority of LCIS is lacking E-cadherin expression, although this is not universal [48]. Mitoses, calcifications and necrosis are rarely found. The basement membrane remains intact and there is no evidence of invasion [49]. Lobular carcinoma in situ is frequently multicentric and bilateral [50].

As with other high risk breast lesions, there is controversy and variation in the literature regarding the upgrade rates and subsequent need for excision. Most series suggest the chance of finding cancer on excision after CNB showing LCIS is around 13–20 %. Again, in most circumstances, excisional biopsy is recommended to rule out malignancy [39].

Women who are diagnosed with LCIS on CNB or excision have the highest relative risk of developing breast cancer in the future; 8–10 times that of the average woman.

In patients with biopsy proven LCIS, reports cite the risk of developing ipsilateral breast cancer varies between 7 and 17 % at 10 years [45, 51, 52]. Contra lateral risk is also significantly increased. Ten year estimate was found to be 13.9 % in this series [53]. Individual patient risk factors such as family history can be additive to this risk.

Pleomorphic LCIS

Pleomorphic LCIS is a variant of LCIS that has recently been recognized as distinct from LCIS. Studies show that in the past, this lesion was in many cases lumped in with the diagnosis of DCIS. Pleomorphic LCIS is more frequently associated necrosis and microcalcifications on pathology or mammography [54].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree