Fig. 9.1

Ultrasound, right transverse

Fig. 9.2

Ultrasound, lymph node

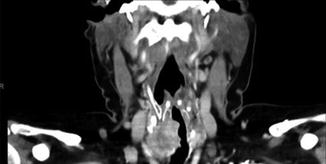

Fig. 9.3

CT showing right thyroid mass

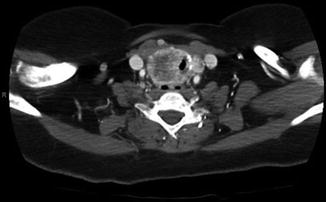

Fig. 9.4

CT

He underwent a total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection, and right modified radical neck dissection. Histopathology showed a 4.3 cm classical papillary thyroid cancer with minimal extrathyroidal extension, 23/50 positive lymph nodes with extranodal extension, and no vascular invasion. Lab data 2 weeks after surgery included TSH 72.33 mcIU/mL, thyroglobulin 9.6 ng/mL, and thyroglobulin antibody <1.8 IU/mL. He underwent radioactive iodine ablation with 100 mCi. Post-iodine treatment scan showed neck uptake only. This patient is considered high risk due to male gender, tumor size >4 cm, and extensive bulky adenopathy with extranodal extension.

Case #3: 56-year-old female presents with a large compressive goiter. Past medical history is notable for radioactive iodine treatment for Graves’ disease 10 years ago. Physical examination revealed stridor and an extensive firm immobile right neck mass. Flexible laryngoscopy confirmed right true vocal cord paralysis. Fine needle aspiration cytology showed papillary thyroid cancer. Computed tomography showed a locally invasive mass with erosion of the cricoid cartilage, tracheal invasion with intraluminal extension, and suspected esophageal invasion (Figs. 9.5 and 9.6). Due to extent of local invasion, the patient was started on systemic therapy with Lenvatinib. This patient is clearly high risk due to extensive local invasion.

Fig. 9.5

CT showing intraluminal invasion, coronal

Fig. 9.6

CT showing intraluminal invasion

Systemic Therapy for High-Risk Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid cancer is almost always treated successfully with a combination of surgery and radioactive iodine ablation. Poorly differentiated thyroid cancer has a high risk for recurrence despite of these treatments. For these patients, there is a definite role of systemic therapies in delaying progression. These drugs are associated with serious, potentially life-threatening toxicity and must be administered correctly to provide benefit to patients.

Overview of Agents, Specifically in Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

Recently approved systemic therapy options for poorly differentiated thyroid cancer include Sorafenib and Lenvatinib, both multikinase inhibitors. The phase 3 DECISION trial compared Sorafenib to placebo in RAI-refractory thyroid cancer [37]. It enrolled 38 patients with poorly differentiated thyroid cancer, and overall there was a benefit toward treatment with Sorafenib [37]. The phase 3 SELECT trial compared Lenvatinib to placebo in RAI-refractory thyroid cancer. It enrolled 47 patients with poorly differentiated thyroid cancer and found an improvement in progression-free survival for patients with poorly differentiated thyroid cancer compared to placebo (HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.08–0.56). Median PFS was 14.8 months compared to 18.3 months for the overall population. Though not directly comparable, lenvatinib was associated with greater response rates in the SELECT trial of approximately 50% compared to Sorafenib which had a response rate of 12% [38].

Timing of Initiation of Therapy

As with treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer, clear goals of therapy are necessary and should be discussed with the patient. With either of the approved drugs, there is no overall survival benefit seen to treatment compared to observation, possibly due to the crossover design of these trials [39–42]. The clinical trials also set stringent criteria for patient entry, and the patient groups were not identical. Patients should be considered for systemic therapy upon development of serious symptoms related to tumor growth, either due to anatomic growth or organ damage. Rapidity of tumor growth is also justification for the initiation of therapy, though that is often subjective and affected by many external factors. Asymptomatic progression often can be observed in differentiated thyroid cancer. In poorly differentiated thyroid cancer, tumors tend to grow more rapidly, and generally there is a lower threshold for starting systemic therapy. Most important is to tailor therapy not to histology but to actual malignant behavior in the patient.

Suitability of Patients

Multikinase inhibitors carry serious, sometimes fatal toxicities. Even with the close monitoring inherent to a clinical trial, there were six deaths in the SELECT trial that were attributable to Lenvatinib [38]. This class of drugs is associated with stroke, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism. Drugs should not be administered to patients with unstable coronary artery disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or cardiovascular event within the last 6 months. However, both agents carry a similar toxicity profile.

Monitoring During Therapy

Two different approaches are often used with systemic therapy; patients may be started at the dose as indicated in the clinical trials and then reduced for toxicity, or they may start at a slightly lower dose and then escalate up to what is tolerated. This decision usually is personalized between the treating clinician and patient based on prior experience and tolerance for toxicity.

Toxicities of these drugs require close monitoring, as indicated in the package insert. Special attention is paid to blood pressure immediately after starting therapy, as well as changes in liver function tests. Though orally administered, patients should regularly be evaluated while on systemic therapy. Initially, this may be as frequent as weekly. Development of toxicity requires adjustment of medication dosage, since toxicity is generally dose-related. Though there are some similarities, there are subtle differences between the toxicity profile of both drugs that should be taken into account.

Assessment of Response

Poorly differentiated thyroid cancer often shows a rapid rate of tumor growth and dissemination. Upon initiation of systemic therapy, visible tumor growths such as those in the neck or skin may respond within weeks to Lenvatinib. Cutaneous or palpable tumors are often used to assess response to therapy, but clinical evaluation does not replace anatomic imaging. This is routinely done with CT scans every 2–3 months while on therapy. While noticeable tumor shrinkage is the desired outcome, it is not uncommon to see variations in tumor size between scans that do not represent true progression. With limited treatment options available, generally maintaining therapy until true progression is preferred. At the time of progression, another multikinase inhibitor may be administered.

Targeted Therapy and Investigational Approaches

Poorly differentiated thyroid cancer does not have the same durability of response as more differentiated thyroid cancer. Therefore, it is likely that patients may experience disease progression while on both multikinase therapies [43–48]. At that point agents not approved for use in poorly differentiated thyroid cancer such as Vandetanib and Cabozantinib may be attempted, though their utility is often limited [49–51]. Genomic analysis may sometimes demonstrate mutations with targeted therapy significance such as a BRAF V600E mutation. In that case BRAF inhibitors such a Vemurafenib may be attempted [52–54]. Other drugs that are in trials and have limited evidence of activity include MEK inhibitors and PI3 kinase inhibitors. In all cases of poorly differentiated thyroid cancers that are refractory to approved therapies, enrolment of the patient in a clinical trial should be the primary consideration.

References

1.

DeLellis RA. Pathology and genetics of tumours of endocrine organs, vol. 1. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. p. 320.

2.

American Thyroid Association Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules, Differentiated Thyroid Cancer, Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167–214.CrossRef

3.

4.

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

5.

6.

7.

8.

Baloch Z, LiVolsi VA, Tondon R. Aggressive variants of follicular cell derived thyroid carcinoma; the so called ‘real thyroid carcinomas’. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:733–43.CrossRefPubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree