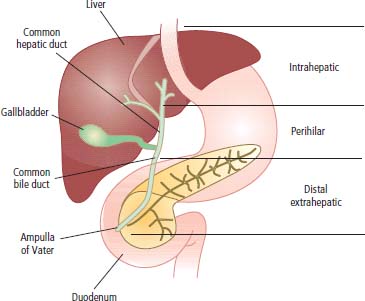

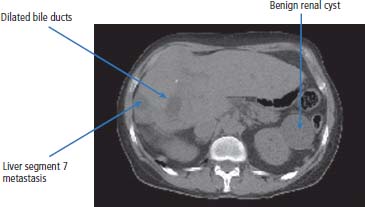

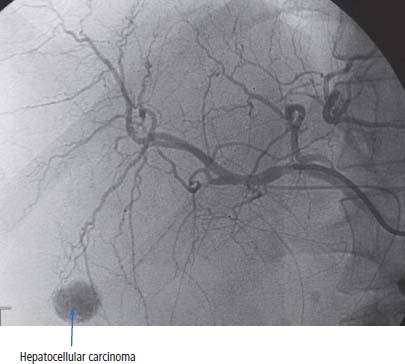

9 Hepatobiliary cancer is the sixth most common malignant tumour in the world. The highest incidences are seen in South East Asia. In the United Kingdom, hepatobiliary cancer is relatively uncommon. In 2011, 4348 men and women were registered with liver cancer and sadly 4106 died. The male to female ratio for liver cancers is 1.7:1 and the risk rises with increasing age with 90% diagnosed in people over 55 years of age. In the United Kingdom the 5-year survival for patients with this cancer is just 5% (see Table 9.1). Primary liver cancers are divided into four main groups of tumour: The aetiology and clinical management of these different tumours varies. HCC is associated with chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Around 2 billion people worldwide are infected with HBV and 10% of people infected with HBV develop chronic HBV, whilst 170 million people are infected with HCV and >80% develop chronic HCV infection if left untreated (see Table 2.10). Table 9.1 UK registrations for hepatobiliary cancer 2010 Chronic HBV infection is prevalent in up to 15% of males in certain populations and the lifetime risk of developing HCC is 40% in this group of men. An epidemiological study of 22,707 Taiwanese male government employees followed over 10 years found that the relative risk of liver cancer was 98 for men with HBV. To put this risk into context, the relative risk for lung cancer amongst smokers is around 17. In a study from the National Cancer Centre in Korea, 74.6% of the patients with HCC were HBV positive. The HBV genome encodes four proteins: C (core protein), P (a DNA polymerase), S (surface antigen) and X (whose function is not clear but acts as a weak oncogene) (see Chapter 2). How chronic HBV causes cancer is unclear, but it is thought that the constant proliferation of hepatocytes caused by the need to replace virus-damaged cells and the chronic inflammatory response in the liver are the main culprits. Support for this hypothesis comes from HCV-induced liver cancer. HBV and HCV are very different viruses genetically, but both cause similar chronic infection and inflammation of the liver and both are associated with a high risk of liver cancer. In terms of the model for chemical carcinogenesis, these viruses appear to act as tumour promoters rather than initiators. This is supported by synergism in risk between chronic HBV infection and mutagens such as aflatoxin B1. Aflatoxin B1 is derived from the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus which commonly infects foods such as peanuts that are stored in damp conditions and which causes mutation of p53. In one study from China, the relative risk of liver cancer in people with chronic HBV was 7, in those exposed to aflatoxin was 3, but in those exposed to both chronic HBV and aflatoxin was 60. HCC are associated with other causes of chronic liver damage including alcoholism and other hepatitides causing cirrhosis such as primary biliary cirrhosis, haemochromatosis and acute and chronic hepatic porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, porphyria cutanea tarda, hereditary coproporphyria and variegate porphyria). Tumours of the biliary tree are divided into (Figures 9.1 and 9.2): Biliary tree tumours occur at increased frequency in primary sclerosing cholangitis with a lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma of 10–20%. Congenital conditions that cause dilatation of the biliary tract such as choledochal cysts and Caroli’s disease also transform into cholangiocarcinoma in 25% of patients. Gallstones and cholecystectomy do not influence the risk of biliary tree cancer. In South East Asia, where these tumours are common, they are seen in association with biliary infestation with liver flukes (Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini) that affect 30 million people worldwide (see Table 2.12). Figure 9.1 Anatomy of biliary tract cancers. Figure 9.2 CT scan demonstrating intrahepatic dilated bile ducts that were due to cholangiocarcinoma. There is also a low attenuation metastasis in segment 7 of the liver and an incidental (benign) renal cyst. The aetiology of hepatoblastoma is not known. Hepatic angiosarcoma is associated with exposure to the vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), choloroethene (C2H3Cl) that is polymerized to the plastic polyvinyl chloride (PVC), that is used to make everything from vinyl records and PVC trousers to guttering and catheters. The mechanism for this is not clear, and the development of this tumour does not always occur in those men and women who have the heaviest exposure to VCM, as for example, in those workers involved in autoclave cleaning in chemical works. When workers exposed to VCM are examined for their lifetime risk of developing angiosarcoma this is overall clearly four times higher than in the general population. Where there is a coincident HBV infection, the risk increases 25-fold compared with the general population. The central role of hepatitis viruses in the aetiology of HCC offers opportunities for primary prevention, eradication and screening as strategies to prevent cancer. A vaccine based on the surface antigen envelope protein of HBV (HBVsAg) protects against the acquisition of HBV. The widespread introduction of this vaccine in Taiwan has been shown to reduce the risk of HCC in children and a similar protection in adults is likely. Second, antiviral therapy against hepatitis B that is effective at lowering HBV titres may reduce the risk of liver cancer amongst people with chronic HBV. Similarly, therapy for chronic HCV may also reduce the risk of HCC in chronically infected individuals and recent advances have led to combination treatments that have high rates of clearing HCV without the use of interferons. Finally, screening people with chronic HCV and HBV may reduce the mortality of liver cancer by diagnosing patients earlier with surgically resectable HCC. Liver ultrasound and serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) screening should be performed every 6 months in patients with chronic HBV or HCV. There are significant concerns with regard to the increasing infection rates with hepatitis C in Europe. It is thought that the risk of developing hepatobiliary cancer in the presence of chronic hepatitis C infection is even greater than that associated with hepatitis B infection. Patients with hepatobiliary cancer generally present with advanced disease. Typical presentations are with jaundice, liver pain and weight loss. A patient with a suspected diagnosis of hepatobiliary cancer should be referred to the appropriate surgical unit for investigation. The management of these conditions is very complex and should only be in centres of excellence with highly specialized surgical units, who achieve significantly better results. Standard investigations for patients with HCC should include blood counts, liver function tests, renal function tests, chest X-rays, ultrasound assessment and CT imaging. Ultrasonography has developed considerably over the last decade, and these technical improvements have been matched by improved standards in endoscopic assessment of the patient. Hepatobiliary cancers are associated with raised serum levels of AFP, which is characteristically raised to many thousands of ng/mL. In patients with cirrhosis, who may have AFP levels raised to a few hundreds of ng/mL, increasing levels point to the development of hepatobiliary cancer. Surprisingly, those patients whose tumours do not secrete AFP are more likely to have favourable outcomes. Hepatobiliary tumours produce other serum markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) which may also be useful in the monitoring progress. The diagnosis of HCC may often be established non-invasively using dynamic imaging modalities (CT, MRI or contrast-enhanced ultrasound) and this avoids the risk of tumour spread at biopsy. Figure 9.3 Selective angiography of the right hepatic artery showing a small area of hypervascularity due to hepatocellular carcinoma. As this was inoperable (there were four other lesions in different segments of the liver), it was treated by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE). Characteristically, patients with cholangiocarcinoma present with obstructive jaundice and usually require biliary drainage. This can be achieved either by a radiologist placing a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drain (PTBD) or by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP) and placement of a biliary stent. Histological confirmation of the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma is usually made at ERCP with needle aspiration or brush cytology or by radiological guided percutaneous biopsy. Hepatobiliary tumours are described as well, moderately or poorly differentiated. Staging for hepatic and biliary tract tumours is according to the TNM classification. Liver resection is the only treatment that offers a chance for cure for liver cancer. Surgery is limited by the degree of spread of the tumour and the presence or absence of background cirrhosis. The aim of surgery generally is to remove the lobe of the liver containing the tumour. Liver transplantation is potentially curative for patients with solitary HCC <5 cm or up to 3 nodules all <3 cm yielding 5-year survival rates above 70%; however, just 10% of patients with liver cancers have operable tumours. When curative surgery is not possible, hepatic transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), percutaneous tumour ablation including radiofrequency ablation sclerotherapy (see Figure 3.12) and systemic anticancer therapy may be appropriate (Figure 9.3). Sorafenib, an oral receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits angiogenesis, has emerged as a valuable palliative treatment for unresectable HCC that prolongs median overall survival from 5.5 to 9.2 months. Unfortunately, treatment with this agent is not allowed in England as a result of an inappropriate, in the view of most oncologists and their patients, decision by NICE. Table 9.2 Five-year survival rates of patients with hepatic and biliary tract cancers Cholangiocarcinomas are chemosensitive but rarely operable. A combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy is currently the gold standard treatment for inoperable cholangiocarcinoma. Five-year survival for patients with operable liver cancer is in the order of 33% when management involves partial liver resection. The 5-year survival of patients transplanted is 80%. The median survival of patients who are not treated with curative intent is 6–7 months (Table 9.2). The median survival of patients in the Far East is much poorer, and the vast majority die within 2–3 months of diagnosis. Case Study: The co-infected Côte d’Ivorian.

Hepatobiliary cancer

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Liver cancer

1

2

19th

14th

1 in 215

1 in 120

+31%

+44%

5.7%

5.1%

Prevention

Presentation

Staging and grading

Treatment

Tumour

5-year survival

Hepatocellular cancer

5%

Gallbladder cancer

5%

Cholangiocarcinoma

5%

Periampullary cholangiocarcinoma

50%

Prognosis

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree