Fig. 5.1

A large HCC in a 75-year-old HCV-positive patient treated by selective internal radiation treatment (SIRT). (a) Angiographic image during SIRT. (b) CT after SIRT. (c) The specimen after a right trisectionectomy. (d) At final pathology, 90% necrosis was evident; resin microspheres were visible in the vessels

Colorectal Liver Metastases (CRLMs)

CRLMs are the most common indication for liver surgery. Since the 1980s, the beneficial impact of resection on prognosis has been clearly demonstrated. Surgery is the established „gold standard” treatment with excellent short- and long-term results (mortality lower than 2%, survival up to 50–60% at 5 years in selected cases) [10, 11], mainly in high-volume centers [12]. Even a curative role of surgery has been recently demonstrated by reports of 10-year actual survivors in 15–20% of cases.

Staging

Together with computed tomography (CT), a significant contribution to staging has been offered by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver. It has achieved extremely high sensitivity and specificity for the detection and characterization of hepatic lesions, especially thanks to contrast agents and diffusion- weighted images [13].

The role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PETCT) is controversial. Even if it offers additional data, the high rate of falsepositive (inflammation) and false-negative (especially after chemotherapy) images limit its impact [13]. It has a role in doubtful cases or in patients with advanced disease to disclose extrahepatic deposits.

Indications

The surgical indications for CRLM have been expanded considerably. The number and diameter of lesions, extra-hepatic disease, and synchronicity of metastases are no longer a contraindication [10]. Patients with lymph-node metastases beyond the hepatic pedicle do not show a clear benefit from surgery and should be cautiously scheduled for resection. The only absolute contraindication is the impossibility of achieving complete surgery. A debate about the adequate width of the surgical margin is ongoing. Evidence suggests that a negative margin is probably sufficient, but de Haas et al. recently reported even a non-negative impact of a 0-mm margin (R1 surgery) [14]. It probably reflects the extension of indications to more complex cases in which large margins cannot be achieved. In these patients, the impossibility to avoid a 0- mm margin does not contraindicate surgery. Nevertheless, it should not be considered a pathway toward palliative surgery.

Recurrences after liver resection often occur (≤60% of cases). Re-resection has the same indications as the first liver resection (surgery whenever technically feasible) with similar survival outcome.

Chemotherapy

In the last 15 years, effective chemotherapy drugs have been introduced, such as oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Median survival in unresectable patients (80–90% of cases) passed the threshold of 20 months. In some cases (≈10–15%), chemotherapy obtains a significant tumor shrinkage that even enables the patient to undergo resection. In 1996, Bismuth et al. were the first to report resection after “conversion chemottherapy”. Several series have reported encouraging long-term results (5-year survival, ≈30%), even if high recurrence rates have been observed [15]. The effectiveness of chemotherapy in unresectable patients let some authors consider its application in “borderline-resectable” cases. The aim was to obtain tumor shrinkage, to enable easier and more conservative resections, and to select good candidates for surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is now commonly adopted even if supported by little evidence. The next step has been the proposal of systematic chemotherapy in all resectable patients. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized trial 40983 published in 2008 (surgery alone vs surgery + perioperative oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy) tried to validate this policy. Even though the primary endpoint (higher diseasefree survival at 3 years in the chemotherapy group) was achieved, the difference was limited (+8%) and no differences in overall survival were observed [16]. Further trials are ongoing to clarify this issue.

Response to Chemotherapy

The response to chemotherapy has been demonstrated to have a prognostic impact. Radiological disease progression at restaging has even been considered to be a contraindication to surgery because of extremely poor outcome (8% at 5 years). More recent studies better reclassified it as a relative contraindication to surgery: in selected patients (up to 3 metastases, <50 mm, CEA <200 ng/mL), resection can be undertaken with good outcome despite disease progression [17]. On the basis of pathological examination, Rubbia- Brandt et al. proposed a tumor regression grade to assess metastatic responses to chemotherapy [18]. It has a strong prognostic impact, clearly more precise than that seen for radiological data.

Disadvantages of Chemotherapy

Firstly, chemotherapy-related liver injuries have been depicted, for example, sinusoidal injuries and nodular regenerative hyperplasia after oxaliplatinbased treatments and steatohepatitis after irinotecan-based therapies. These lesions increase postoperative morbidity and, in case of steatohepatitis, even surgical mortality due to liver failure [19]. Chemotherapy-related liver injuries increase together with the number of chemotherapy cycles, whereas their clinical impact decreases upon prolonging the interval between chemotherapy and surgery. A short duration of chemotherapy and an adequate interval between chemotherapy and surgery are the rules to respect to limit these problems.

A further disadvantage of chemotherapy is the disappearance of metastases, especially small ones. Unfortunately, this finding does not correspond to the true sterilization of neoplastic foci. In 2006, Benoist et al. showed that 80% of disappeared lesions either was still present at surgery or recurred at follow-up [20]. More favorable data have been reported by recent studies (residual disease in only 30%), especially if intra-arterial chemotherapy was administered. In any case, surgeons should look at the radiological disappearance of CRLMs with suspicion.

Targeted Therapies

In association with chemotherapy, targeted therapies show a significant contribution to disease control and tumor shrinkage. The most common targeted therapies are bevacizumab (anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody) and cetuximab (anti-VEGF-A antibody). Their association with chemotherapy increases the response rate by up to 78%. Even a benefit in terms of overall and progression-free survival has been reported [21, 22]. With regard to cetuximab, a molecular predictor of effectiveness has been identified: the k- Ras gene. Only patients with a wild-type k-Ras gene may benefit from this treatment. A prognostic impact of k-Ras mutations has been also suggested.

Surgical Strategies

Due to the excellent outcome of surgery, surgeons have implemented strategies to increase resectability to offer a chance of cure to as many patients as possible. In those with multiple bilobar lesions, the need for complete surgery has to be integrated with the need for an adequate future liver remnant (FLR). In 2000, Adam et al. proposed a two-stage hepatectomy to solve this problem. They scheduled two subsequent liver resections to achieve R0 surgery to allow liver hypertrophy between the two procedures. This procedure was better codified by Jaeck et al. in 2004: (i) extirpation of lesions in the planned FLR, usually the left lobe, during the first operation; (ii) portalve in occlusion, usually the right one (intraoperative ligation or postoperative embolization); (iii) major hepatectomy (usually a right hepatectomy or right trisectionectomy) 4 weeks later provided adequate FLR hypertrophy [23]. About 75–80% of patients will complete the treatment and achieve excellent long-term results (5-year survival of 30–50%), similar to those observed after one-stage resections. Recently, a new proposal has been advanced: the association of liver partition to portalvein ligation at the time of the first resection to achieve an extremely rapid volume increase (within 1 week). This strategy, called „associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy” (ALPPS), allows completion of the second procedure within the same hospitalization (7–10 days after the first procedure) and avoids the drop-out risk between the first and second stage [24]. Only few preliminary reports are available on ALPPS.

Another important issue is the management of patients with synchronous metastases. The debate between simultaneous and delayed resection is ongoing, but an interesting new proposal has been advanced: the „reverse strategy”. Mentha et al. reported it first in 2006. The authors proposed to treat first the liver metastases and then the primary tumor in two separate procedures. This strategy allows prioritizing hepatic deposits, which are the true determinants of the prognosis. In 2012, the Mentha research team compared this strategy with the classic approach (colorectal resection followed by liver surgery): the reverse approach guaranteed the same outcome as the standard one [25]. In the authors’ opinion, the reverse strategy is of interest, especially for patients with locally advanced rectal tumors in whom chemoradiotherapy before rectal surgery should be scheduled. Theoretically, reverse strategy allows carrying out chemoradiotherapy after having completed liver surgery before rectal resection. Ad hoc trials are needed to clarify this issue.

Finally, it is important to underline the evolution of surgery in CRLM treatment towards a parenchymal-sparing policy. Major liver resections are carried out less often to reduce the risk of liver dysfunction and to increase the opportunities of re-resection. Wedge resections and segmentectomies guarantee adequate ongological treatment if planned appropriately. Intraoperative ultrasonography is an essential tool to safely undertake these resections (Fig. 5.2).

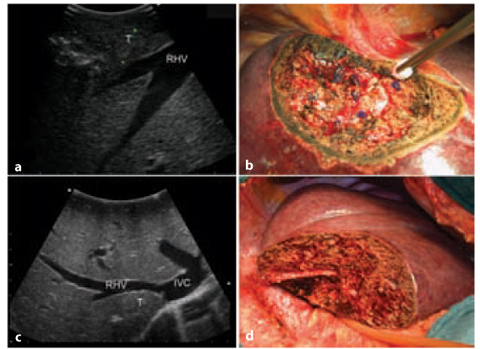

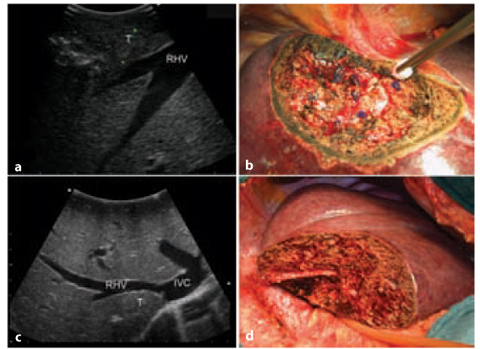

Fig. 5.2

Parenchymal-sparing strategy in resection of colorectal liver metastases. (a) Intraoperative ultrasonography shows a metastasis in contact with the right hepatic vein without infiltration. (b) Wedge resection of segments 7 and 8 sparing the right hepatic vein that has been exposed on the raw cut surface. (c) Intraoperative ultrasonography shows a metastasis compressing (but not infiltrating) the right hepatic vein. (d) Resection of Sg7 with exposure of the right hepatic vein on the raw cut surface

Interstitial Treatments

After their successful application in HCC, interstitial treatments have been proposed for CRLMs. Their appeal relies on easy application, brief hospitalization, and excellent short-term outcome. Anyway, strong evidence is against their application to resectable CRLMs [26]. In comparison with surgery, RFA is associated with higher local recurrence rates and lower overall and diseasefree survival. The same poor results have been observed even for small lesions (<3 cm). RFA is not an alternative to surgery. It can be combined with surgery to achieve complete treatment by ablating deeply located lesions that were otherwise unresectable. Even for these patients, outcome is lower in comparison with those receiving surgery alone.

Biliary Tumors

In comparison with CRLMs, biliary tumors have had a more limited evolution in recent years. This is due to their rarity, the need for large and high-risk surgical procedures (mortality rates, 5–10%) and the lack of effective medical treatments.

It is possible to distinguish intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor), distal bile duct cancer, and gallbladder cancer. Tumors of the middle bile duct are no longer considered because, according to the level of tumor, hepatic or pancreatic surgery is needed.

Peripheral Cholangiocarcinomas (CCCs)

CCCs have had a marked increase of incidence in recent years. This finding could be partly related to their improved diagnosis: hepatic lesions previously classified as „liver metastases of unknown origin” are now correctly identified as CCC.

With respect to surgical treatment, few series are available. Some recent multicenter studies tried to codify indications and outcome [27, 28]. Surgical mortality was ≈5%, but excellent survival results have been reported (≈40% at 5 years). Resection is indicated if complete surgery can be done, but radical resection is finally achieved in only 75–85% of patients. Lymph-node dissection is essential in all patients because of the high percentage of N+ patients (more than one-third of cases). Metastatic lymph nodes are not an absolute contraindication to surgery but are associated with poor outcome. Together with R1 resection, N status is the strongest prognostic determinant.

Hilar Cholangiocarcinomas

The treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinomas has had several modifications in recent years [29]. Preoperative staging can be complete without invasive examination: CT and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) clearly show the biliary and radial extension of the tumor. The surgical procedure is now standardized. Isolated bile duct resection has been abandoned in almost all patients. The mucosal and submucosal spread of cancer requires wide margins. The combination of biliary and liver surgery increases the completeness of resection and prolongs survival. Similarly, segment 1 must be removed systematically because it can be a site of direct infiltration by the tumor or perineural/biliary neoplastic diffusion. Lymph-node dissection should be systematic because of the high risk of metastatic deposits (30% to 60%), but positive lymph nodes at the hepatic pedicle do not contraindicate resection.

Liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinomas has been traditionally associated with high mortality rates (up to 10–15%). A combination of biliary drainage and portal-vein embolization in patients with inadequate FLR has improved the safety of these procedures, even reaching 0% mortality in some series. Nevertheless, the indications for preoperative biliary drainage are controversial because not all patients need it (low bilirubin values, left-sided resections) and because severe sepsis due to bile-duct contamination may occur. Biliary drainage is essential whenever portal-vein embolization is required, and should drain only the FLR.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree