some cell types, such as Hodgkin’s disease, the rate of positive cytology results may prove as low as 23%, while with others, such as breast or lung cancer, remain as high as 73% (3).

TABLE 30.1 Tumor causes of malignant pleural effusions from collected series | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 30.2 Available intrapleural sclerosing agents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

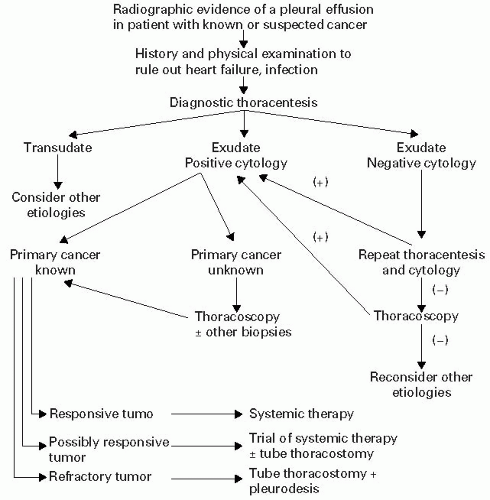

should reflect the clinician’s realistic understanding of the patient’s overall prognosis along with motivation to provide the maximum quality of life and function. A suggested treatment algorithm for malignant pleural effusions is shown in Figure 30.2.

chest x-ray should provoke consideration of a pericardial effusion. The cardiac silhouette might resemble the so-called water-bottle heart with bulging of the normal contours. However, a normal-size heart shadow does not exclude the presence of a pericardial effusion or even a life-threatening tamponade. A chest CT scan is more sensitive and may suggest a malignant pericardial process if the effusion has a high density, there is pericardial thickening, masses are contiguous with the pericardium, or there is an obliteration of the tissue planes between the mass and the heart (26).

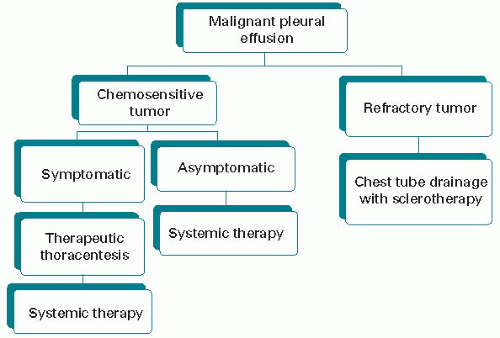

be individualized, taking into consideration tumor cell type and sensitivity to disease-modifying therapies, patient performance status and prognosis, and presence/absence of pericardial tamponade, leading to some meaningful period of palliation. A suggested treatment algorithm for patients with chemosensitive tumor is shown in Figure 30.3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree