Up-front rituximab-based chemotherapy has improved outcomes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL); refractory or relapsed NHL still accounts for approximately 18,000 deaths in the United States. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) can improve survival in primary refractory or relapsed aggressive NHL and mantle cell lymphoma and in relapsed follicular or peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Autologous SCT as a consolidation therapy after first complete or partial remission in high-risk aggressive NHL, mantle cell lymphoma, and peripheral T-cell lymphoma may improve progression-free survival. Allogeneic SCT offers a lower relapse rate but a higher nonrelapse mortality resulting in overall survival similar to autologous SCT.

Key points

- •

Autologous stem cell transplantation can improve survival in primary refractory or relapsed aggressive B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma as well as in relapsed follicular or peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

- •

Autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission in selected patients with high-risk aggressive B-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and peripheral T-cell lymphoma is associated with improved progression-free survival.

- •

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation offers a lower relapse rate but a higher nonrelapse mortality resulting in overall survival similar to autologous stem cell transplantation.

- •

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation can be considered in select patients who fail induction therapy, autologous stem cell transplantation, or are ineligible for autologous transplant.

Introduction

With the lifetime probability of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) of approximately 2%, NHL is a leading cause of cancer with an estimated 70,800 new diagnoses in the United States in 2014. Although the 5-year survival of NHL has improved from 47% (1975–1977) to 71% (2003–2009) in the last 3 decades, NHL is estimated to account for 18,990 deaths in the United States in 2014. This finding highlights a need for an improvement in up-front and salvage therapy for NHL. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) is a therapeutic option, which may offer a survival benefit to select patients, as described later.

Introduction

With the lifetime probability of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) of approximately 2%, NHL is a leading cause of cancer with an estimated 70,800 new diagnoses in the United States in 2014. Although the 5-year survival of NHL has improved from 47% (1975–1977) to 71% (2003–2009) in the last 3 decades, NHL is estimated to account for 18,990 deaths in the United States in 2014. This finding highlights a need for an improvement in up-front and salvage therapy for NHL. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) is a therapeutic option, which may offer a survival benefit to select patients, as described later.

Patient evaluation overview

A multidisciplinary approach to patient selection may reduce transplant-related mortality (TRM) and morbidity ( Table 1 ). Hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT CI) predicts nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and survival in allogeneic SCT (alloSCT) for hematologic malignancy as well as autologous SCT (autoSCT) for lymphoma. HCT CI is more sensitive and has a better survival prediction than the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Additionally, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and the absence of chemosensitivity also predict higher NRM. Patients who are older than 60 years are frequently not considered good candidates for myeloablative alloSCT but may be eligible for nonmyeloablative alloSCT. The presence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B or C does not preclude autoSCT but may require further evaluation and close monitoring. The role of alloSCT in patients with HIV is currently not established.

| Rational | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Restaging of NHL | CT or PET scan, bone marrow and lymph node biopsies |

| Risk assessment for TRM | Performance status, nutritional and psychosocial status, viral serologies (particularly for alloSCT), cardiopulmonary, renal and liver function tests |

| Key eligibility criteria | Karnofsky performance score ≥70%, ejection fraction ≥40%, DLCO ≥50%, and serum creatinine clearance of ≥50 mL/min for autoSCT; also serum total bilirubin <2 times the upper limit of normal for alloSCT |

Indications of transplantation

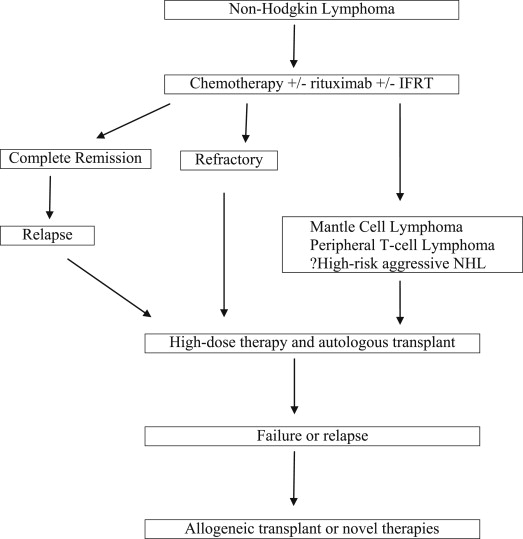

High-risk aggressive B-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphoma, and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (TCL) have poor overall survival (OS) with conventional chemotherapy and are candidates for high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) followed by autoSCT or alloSCT ( Fig. 1 , Table 2 ).

| Lymphoma Type | Indication for AutoSCT | Indication for AlloSCT |

|---|---|---|

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

|

|

| Follicular/indolent lymphoma |

|

|

| MCL |

|

|

| Peripheral TCL |

|

|

| Burkitt |

|

|

Transplantation in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) consisting of approximately one-third of all NHL is the most common aggressive NHL. It can arise de novo or as a transformation of indolent lymphoma, such as follicular lymphoma (FL). Although rituximab-based immunochemotherapy has improved OS in DLBCL, high-intermediate–risk or high-risk disease is associated with a 4-year OS of 49% to 59%. SCT has been extensively investigated in both up-front and salvage settings.

Up-front Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Aggressive Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Several trials have failed to show an OS benefit with up-front HDT/autoSCT in DLBCL or other aggressive NHL. A meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials (n = 3079) highlighted a similar TRM ( P = .14) and higher complete remission rate ( P = .004) but no improvement in event-free survival (EFS) ( P = .31) or OS ( P = .58) with HDT/autoSCT, compared with conventional chemotherapy, in aggressive NHL. Therefore, up-front autoSCT is not indicated in an unselected population of aggressive NHL. High-intermediate–risk or high-risk DLBCL is associated with an EFS of approximately 50% at 3 to 4 years. Hence, several studies have explored the possibility of a survival increment with up-front HDT/autoSCT in this subgroup of patients. In one of the first trials, LNH-87, up-front autoSCT in aggressive lymphomas offered no OS benefit; however, a retrospective subgroup analysis showed improved progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in high-intermediate–risk and high-risk patients. A recently reported multicenter Southwest Oncology Group trial 9704 randomized high-intermediate–risk or high-risk aggressive NHL to one additional cycle of chemotherapy, followed by autoSCT (n = 125) or 3 additional cycles of chemotherapy (n = 128). Eligible patients had received and responded to 5 cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) or CHOP-rituximab (CHOP-R). Grade 3 to 4 toxicities were significantly higher with autoSCT. At 2 years, there was an improvement in PFS (69% vs 55%, P = .005) but no difference in OS (74% vs 71%, P = .30) with autoSCT compared with chemotherapy. A higher success rate of salvage therapy in patients, who relapsed after initial chemotherapy, explains the lack of OS advantage. A subset analysis showed improved OS with autoSCT for the high-international prognostic index (IPI) group (82% vs 64%, P = .01). Several prior trials, with important differences in their designs, have not shown an OS advantage with HDT/autoSCT in high-risk disease. Improved risk stratification based on the cell of origin, the presence of double-hit rearrangement or gray-zone lymphomas, and interim positron emission tomography (PET) positivity may enhance patient selection in addition to IPI for future trials. Conversely, improvement in up-front therapy may reduce the benefit of consolidation HDT/autoSCT.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Refractory or Relapsed Aggressive Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Approximately 10% to 15% of patients are refractory to primary rituximab-based therapy or progress soon afterward. An additional one-third of patients relapse within 2 to 3 years after the initial therapy. Outcomes are generally poor in these patients with chemotherapy alone. Patients who respond to salvage therapy have chemosensitive disease and are taken to HDT/autoSCT if they are transplant candidates ( Table 3 ).

| Author, Ref. Year | N | Characteristics | Salvage Therapy | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philip et al, 1995 | 215 | Relapsed | Chemotherapy vs HDT/autoSCT | 53% vs 32% at 5 y |

| Vose et al, 2001 | 184 | Induction failure | Various before HDT/autoSCT | 37% at 5 y |

| Kewalramani et al, 2000 | 85 | Induction failure | ICE before HDT/autoSCT | 52% at 3 y among patients who underwent transplant |

| Kewalramani et al, 2004 | 36 | Refractory or relapsed | RICE before HDT/autoSCT | 67% at 2 y among patients who underwent transplant |

| Khouri et al, 2005 | 67 | Relapsed | High-dose R plus chemotherapy before HDT/autoSCT | 80% at 2 y |

| Vose et al, 2004 | 429 | First relapse vs second complete remission | Various or none before HDT/autoSCT | 38% vs 55% at 3 y |

| Gisselbrecht et al, 2010 | 396 | Refractory or relapsed | RICE vs RDHAP before HDT/autoSCT | 47% vs 51% ( P = .4) at 3 y |

AutoSCT in patients with primary refractory NHL have worse outcomes than relapsed patients who had previously achieved complete remission. However, select patients with primary refractory disease still benefit from autoSCT. An Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry study among primary refractory diffuse aggressive NHL (n = 184) treated with HDT/autoSCT demonstrated a complete remission rate of 44% as well as 5-year PFS and OS of 31% and 37%, respectively. Adverse prognostic factors included chemotherapy resistance, a Karnofsky performance status score less than 80 at autoSCT, 55 years of age or older at autoSCT, history of 3 or more prior chemotherapy regimens, and no delivery of involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT) before or after autoSCT. In another study among primary refractory aggressive NHL (n = 85), autoSCT resulted in 3-year EFS and OS of 44% and 52%, respectively. An extranodal site of disease greater than 1 and a second-line age-adjusted IPI of 3 to 4 predicted poor outcomes. Thus, autoSCT should be considered in select transplant-eligible primary refractory patients who have chemosensitive disease to salvage therapy.

Several studies have established the benefit of autoSCT in relapsed aggressive NHL, which is the current standard in transplant-eligible patients. The PARMA trial of relapsed NHL (n = 215) randomized chemosensitive patients treated with 2 cycles of conventional chemotherapy to radiation and HDT/autoSCT (n = 55) versus 4 cycles of chemotherapy and radiation (n = 54). The response rates (84% vs 44%), 5-year EFS (46% vs 12%), and 5-year OS (53% vs 32%) were significantly higher in the autoSCT group. The Collaborative Trial in Relapsed Aggressive Lymphoma (CORAL) trial compared 2 salvage regimens before autoSCT for CD20+ DLBCL in first relapse or primary refractory disease (n = 396). There was no significant difference in response rates after 3 cycles of chemotherapy (63% vs 62%), 3-year PFS (31% vs 42%, P = .4), and OS (47% vs 51%, P = .4) for the rituximab, ifosfamide, etoposide, and carboplatin (RICE) and the rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (RDHAP) arms, respectively. Prognostic factors included refractory disease or early relapse within 12 months after diagnosis, high IPI, and prior rituximab use. Patients with an early relapse after rituximab-based therapy had a poor prognosis, whereas prior rituximab use did not affect EFS in patients who relapsed greater than 12 months after the diagnosis. A subsequent analysis of the CORAL trial assessed the impact of the cell of origin (by Hans algorithm) on the outcomes of salvage therapy and autoSCT. Among the patients treated with RDHAP, the 3-year PFS (52% vs 32%, P = .01) and OS (61% vs 45%) were higher for the germinal center B-cell (GCB) type compared with non-GCB DLBCL. However, the 3-year PFS (31% vs 27%, P = .81) and OS (50% vs 49%) did not differ for GCB and non-GCB DLBCL treated with RICE therapy. The prognostic relevance of the cell of origin was maintained in a multivariate analysis. This study suggests that RDHAP may be a better salvage regimen for patients with relapsed/refractory GCB DLBCL who are fit to tolerate this therapy. In 2 studies using salvage chemotherapy followed by HDT/ASCT, the cell of origin of relapsed or refractory DLBCL, as determined by immunohistochemistry, did not predict outcomes. The prognostic role of the cell of origin is debated in the setting of HDT/autoSCT; however, the authors’ current approach is to offer RDHAP as a preferred salvage therapy to young and fit patients with GCB DLBCL.

Improving the Outcomes of Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

Several strategies including radioimmunotherapy, radiotherapy, and rituximab have been investigated to improve the outcomes of autoSCT. Multiple phase I and II trials have evaluated the role of radioimmunotherapy ( 131 I-tositumomab or 90 Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan) with HDT before autoSCT and shown promising results. A subsequent phase III Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) 0401 trial compared rituximab–carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) and 131 I-tositumomab–BEAM in chemosensitive persistent or relapsed DLBCL (n = 224). The results showed no difference in the 2-year PFS (48% vs 47%, P = .94) and OS (65% vs 61%, P = .38) between the two groups. The use of radioimmunotherapy, therefore, cannot be recommended outside of a clinical trial.

The role of IFRT before autoSCT was addressed by a retrospective study among 164 patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL. IFRT (30 Gy as 1.5-Gy fractions twice daily) was delivered to involved sites greater than 5 cm or areas with residual disease greater than 2 cm. The addition of IFRT was associated with low local relapse and minimal TRM and morbidity. The delivery of IFRT before or after autoSCT has been shown to be prognostic among primary refractory patients treated with autoSCT. IFRT should be used before or after autoSCT in patients with bulky or residual disease.

Among patients without prior rituximab exposure, rituximab use during salvage therapy before HDT/autoSCT may improve PFS and OS. Additionally, rituximab use with HDT before autoSCT has been demonstrated to improve outcomes in high-risk treatment-naïve aggressive NHL as well as in relapsed/refractory settings; however, in these studies, first-line chemotherapy did not include rituximab, thus, limiting the applicability of these studies in the rituximab era. Rituximab maintenance after autoSCT has shown conflicting results and remains investigational.

Predicting the Outcomes of Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

Various clinical factors, such as age-adjusted IPI, an extranodal site of disease greater than 1, increased LDH at diagnosis, older age, and poor performance status predict poor outcomes. Primary refractory disease, refractory relapse, and disease relapse within 12 months of the diagnosis are important predictors of poor outcomes. A history of 3 or more prior chemotherapy regimens has also been shown to correlate with poor outcomes. Hence, transplant-eligible patients should undergo HDT/autoSCT in the first relapse. In addition to the clinical factors, retrospective studies have shown better outcomes in patients with a negative PET scan before autoSCT. In one study, however, there was no difference in EFS among patients with a negative pre-autoSCT and post-autoSCT PET scan compared with patients with a positive pre-autoSCT but negative post-autoSCT PET scan. The author concluded that HDT/autoSCT can improve the poor prognosis conferred by positive pre-autoSCT PET in select patients who attain a negative PET status after autoSCT. Although a positive pre-autoSCT PET scan may be prognostic, whether a positive PET should change the management remains unanswered.

Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation for Diffuse Large B-Cell lymphoma

Patients with DLBCL who fail multiple chemotherapies or autoSCT have poor outcomes, with a median OS of approximately 10 months in the rituximab era. These patients may be candidates for alloSCT. A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) study compared the outcomes of first autoSCT (n = 837) or matched sibling myeloablative alloSCT (n = 79) performed between 1995 and 2003 in patients with DLBCL who were older than 18 years. AlloSCT recipients, compared with autoSCT recipients, were more likely to have a higher stage (stage III/IV disease 80% vs 66%), marrow involvement at diagnosis (42% vs 17%), more prior chemotherapy regimens (≥3 prior regimens 51% vs 41%), and resistant disease (42% vs 15%). The risk of grades 2 to 4 acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) at 100 days of alloSCT was 42%, whereas the risk of chronic GVHD at 5 years was 26%. At 5 years, the risk of TRM (45% vs 18%) was higher and progression or relapse (33% vs 40%) was lower with alloSCT compared with autoSCT. The 5-year PFS and OS with alloSCT, compared with autoSCT, were 22% versus 43% and 22% versus 49%, respectively. In this retrospective analysis, the high TRM offset the lower disease progression or relapse with alloSCT. Nonetheless, alloSCT can result in meaningful 5-year OS in high-risk patients, including heavily pretreated and chemoresistant patients.

A European Bone Marrow Transplantation Registry (EBMTR) study assessed the outcomes of matched-related donor or matched-unrelated donor (MUD) alloSCT with a myeloablative conditioning regimen (n = 37) or reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) (n = 64) for DLBCL relapsed after autoSCT. The 3-year NRM, relapse rate, PFS, and OS were 28%, 30%, 41%, and 53%, respectively. NRM was significantly higher for patients older than 45 years and for those with an early relapse (<12 months) after autoSCT. The relapse rate was higher in refractory patients; PFS was lower among early relapsers (<12 months) after autoSCT. Thus, alloSCT is a therapeutic option after failure of autoSCT particularly among younger patients with a long remission after autoSCT.

Another CIBMTR study among refractory or relapsed DLBCL treated with myeloablative (n = 165), RIC (n = 143) and nonmyeloablative (n = 88) conditioning before alloSCT demonstrated a higher 5-year NRM (56% vs 47% vs 36%, P = .007), lower 5-year relapse/progression (26% vs 38% vs 40%, P = .031), and similar 5-year PFS (15%–25%) and OS (18%–26%) with myeloablative compared with RIC and nonmyeloablative conditioning. NRM was lower with nonmyeloablative conditioning and more recent transplant year and higher with lower Karnofsky performance status (<90), prior relapse-resistant disease, and use of MUD. Nonmyeloablative conditioning, no prior use of rituximab, and prior relapse-resistant disease were associated with a higher rate of relapse/progression. Taken together, these studies indicate that alloSCT is associated with higher TRM but lower relapse rates than autoSCT. AlloSCT is a viable option in young patients with relapsed DLBCL, including those who have failed autoSCT. The outcomes are better among patients with good performance status, young age, chemosensitive disease, and who relapse greater than 12 months after autoSCT. RIC or nonmyeloablative conditioning may reduce NRM, possibly expanding its utilization to older patients.

Transplantation in indolent and follicular lymphomas

FL, composing approximately 22% of all NHL, is the most frequent indolent lymphoma. Despite achieving complete remission with initial therapy, patients with FL have frequent relapses and are frequently incurable with conventional therapy. In one study, approximately 10% of the patients with FL were primary refractory to first-line rituximab-based therapy and an additional one-third relapsed within 3 years. SCT has been attempted in both up-front and relapse settings to improve survival.

Up-front Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Follicular Lymphomas

Several studies have shown an improved PFS with consolidating autoSCT in first remission. In the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) trial, patients with advanced FL (n = 240) received CHOP-like induction therapy and then were randomized to autoSCT or interferon-α maintenance until disease progression. The 5-year PFS was significantly higher (64% vs 33%, P <.0001) in the autoSCT group; the relatively short follow-up precluded the determination of OS. In the French Groupe Ouest-Est d’Etude des Leucémies et Autres Maladies du Sang (GOELAMS) study, patients with advanced FL (n = 172) were randomized to immunochemotherapy or HDT/autoSCT with an ex vivo purged graft. AutoSCT resulted in a higher response rate (81% vs 69%, P = .045) and 5-year EFS (60% vs 48%, P = .05) but similar 5-year OS (84% vs 78%, P = .49). The lack of OS advantage was related to an 18% risk of secondary malignancies within 5 years after autoSCT. A longer follow-up of the study showed a plateau in PFS 7 years after HDT/autoSCT, suggesting the possibility of cure in a subgroup of patients; however, the 9-year OS remained similar in the two groups. In the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) trial, patients with advanced FL (n = 401) were randomized to CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without autoSCT. AutoSCT, compared with chemotherapy alone, did not improve 7-year EFS (38% vs 28%, P = .11) or OS (76% vs 71%, P = .53). These studies from the prerituximab era indicate a possible improvement in PFS with autoSCT; however, the results are less relevant in the rituximab era.

In the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) trial, high-risk patients with FL (n = 134) were randomized to R-CHOP versus rituximab-supplemented HDT/autoSCT. AutoSCT, compared with chemotherapy, resulted in a higher complete remission rate (85% vs 62%, P <.001) and 4-year EFS (61% vs 28%, P <.001) but similar OS (81% vs 80%, P = .96). Molecular remission, more commonly seen with autoSCT, was the strongest predictor of outcomes. Seventy-one percent of patients who relapsed after R-CHOP received HDT/ASCT, which resulted in a complete remission rate of 85% and a 3-year EFS of 68%. Given these results and the possibility of secondary malignancies, in the rituximab era, HDT/autoSCT may be best used in the relapsed setting in FL.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Refractory or Relapsed Follicular Lymphomas

AutoSCT has been associated with excellent OS in patients with relapsed FL ( Table 4 ). In the randomized European CUP trial among patients with relapsed FL (n = 140), the 2-year PFS and 4-year OS were significantly higher with unpurged (58% and 71%) or purged (55% and 77%) autoSCT compared with CHOP chemotherapy alone (26% and 46%); however, there was no benefit with purging. In another study, the survival advantage with autoSCT was observed regardless of the frontline rituximab exposure. In a study done at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, a histologic grade of FL 3, a high-risk FLIPI score at the time of autoSCT, and prior exposure to 3 or more chemotherapy regimens predicted worse OS and PFS. The use of a conditioning regimen incorporating monoclonal antibody decreased the risk of progressive FL. Thus, SCT earlier in the disease course and the use of a monoclonal antibody-based conditioning regimen may improve outcomes. An EBMTR study demonstrated that an age of 45 years and older, chemoresistant disease, and total body irradiation (TBI)-containing regimens are predictive of shorter OS. The 5-year NRM was 9%, which was higher among patients aged 45 years and older, refractory disease, and TBI-containing regimens. At a median of 7 years, 9% developed a second malignancy, including secondary myeloid neoplasms (5.7%), mainly in patients who had received TBI. A plateau in the PFS curve was seen with a long follow-up, suggesting a possibility of cure in a subset of patients. Thus, HDT/autoSCT improves outcomes in patients with relapsed FL; young patients with chemosensitive disease should undergo HDT/autoSCT in second remission following the use of a non-TBI monoclonal antibody-based conditioning regimen.

| Author, Ref. Year | N | Characteristics | Salvage Therapy | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schouten et al, 2003 | 140 | Relapsed | Conventional chemotherapy vs HDT/autoSCT | 46% vs 70 + % a at 4 y |

| Le Gouill et al, 2011 | 175 | Relapsed or refractory after rituximab-based induction | Conventional chemotherapy vs HDT/autoSCT | 92% vs 63% at 3 y |

| Vose et al, 2008 | 248 | Relapsed or refractory | HDT/autoSCT | 63% at 5 y |

| Montoto et al, 2007 | 693 | First remission, relapsed or refractory | HDT/autoSCT | 52% at 10 y |

| Evens et al, 2013 | 135 | Relapsed or refractory after rituximab-based induction | HDT/autoSCT | 87% at 3 y |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree