Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Supportive Care

Nina L. Bray

Ann M. Berger

INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a process that worldwide more than 50,000 patients undergo each year (1). HSCT refers to the administration of hematopoietic progenitor cells from any source (e.g., bone marrow, peripheral blood, and umbilical cord blood) or donor (e.g., allogeneic and autologous) to reconstitute the bone marrow in efforts to treat disorders such as malignancies, genetic disorders, and bone marrow failure due to other causes.

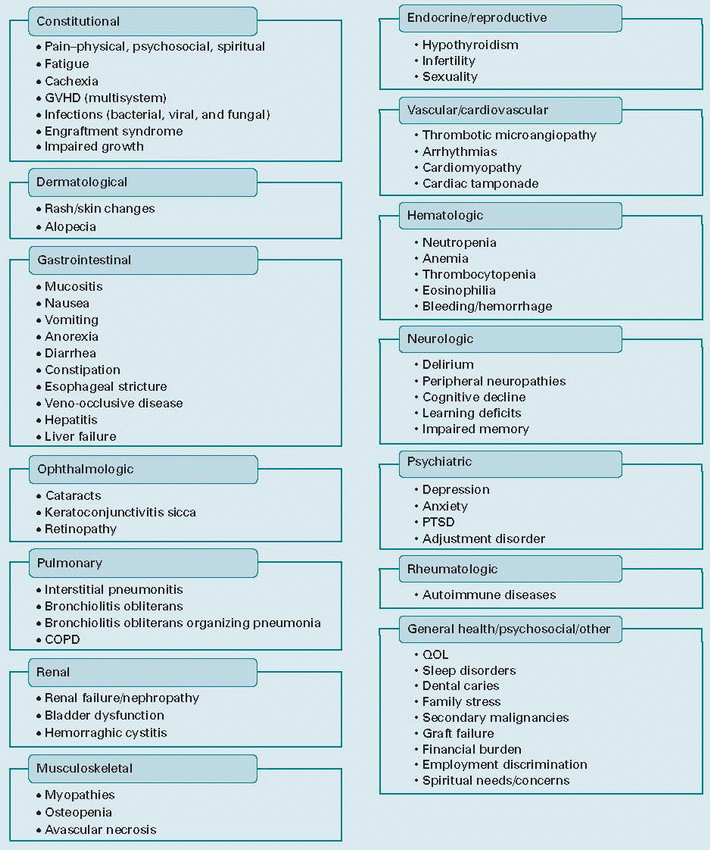

HSCT is a lengthy process endured by patients and their families with many substantial side effects and complications (Table 64.1). It dramatically changes the lives of these patients and families in many dimensions, and improved transplantation strategies have contributed to survival increments of 10% per decade (2). Patients who survive for 2 years after allogeneic HSCT now have survival rates that exceed 80% at 15 years (3,4), and survival rates approach 70% at 10 years following autologous HSCT (5). However, these patients still have to contend with numerous short- and long-term complications; thus, it is important to increase the emphasis of their care on additional supportive techniques that will bolster them through the process of survival. Our goal is to address the challenges of this process and how the medical community can tackle them. Some of the obstacles these patients face have been dealt with in the topics that are covered in other chapters in this book; thus, this chapter will focus on the specific concerns pertaining to overall quality of life (QOL) enhancement in the holistic supportive care of the HSCT patient.

QUALITY OF LIFE

As we discuss some of the complications and the proposed interventions, it is important to note that patients do not experience these complications in discrete units, but in symptom clusters of varying magnitude and scope (6,7). There are models of these symptom clusters; however, it is of critical importance to recognize these not just as symptoms or clusters of symptoms but to realize that these clusters occur in the wider context of their lives. This realization is critical because it helps the clinician recognize that while each symptom is of great concern at the time of presentation, these symptoms are just a portion of the overall effect on the patient. Specifically, as patients consider the process of HSCT, they question not only what these individual complications will be but also what their QOL will be following transplant. Generally, QOL is difficult to measure as inherently it is a multidimensional, dynamic, and subjective concept that encompasses every dimension of a person’s life including good health, adequate housing, employment, personal and family safety, good relationships, education, and enjoyment of leisurely pursuits. As the numbers of survivors increase, it is more and more important to further evaluate and improve QOL, especially as issues related to QOL are routinely cited by cancer survivors as among their greatest concerns (8). However, there is evidence that suggests that transplant physicians consider QOL as a secondary to the curative potential of HSCT, underestimate patient’s symptoms, and overestimate QOL (3,9). Patients often describe significantly more distress from their symptoms than are even recognized by their medical providers (10).

Bury (11) describes illness as a “biographical disruption” in which a person’s life story is disrupted in the light of their illness, the treatment demands, and the many changes that occur. In this chapter, we hope to emphasize that supportive care of the HSCT patient centers on the patient’s life story, relating both to their QOL and their need for holistic supportive care. In covering some of the complications of the process of HSCT, we hope to highlight some of the main factors that affect QOL and propose interventions that can help improve QOL in these patients. In addition, we also hope to help the clinician to better listen and more fully appreciate the stories of our patients so that we can truly help all.

HEALTHCARE TEAM/MULTIDIMENSIONAL MODEL OF CARE

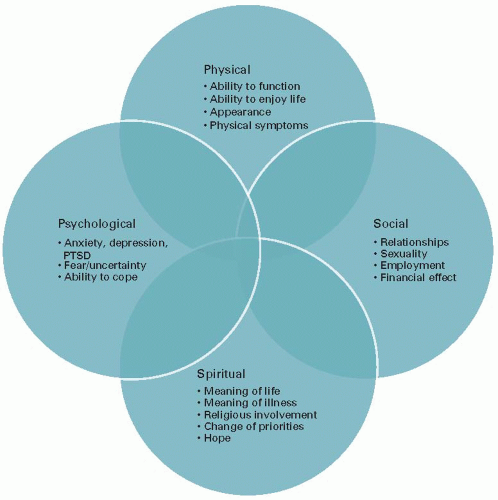

Evaluation of HSCT transplantation is a complex process, it has wide variability across transplant centers, and there are no formal guidelines to conduct pre-HSCT evaluation (12). There is also wide variation in supportive care practices in HSCT (13). From the time patients contemplate the process through the time years later when they are looking back on it, likely forever changed, they experience the effects in all dimensions of their lives—physical, psychological, social, and spiritual (Fig. 64.1). The effects extend beyond these groupings but the model is a useful starting place from which healthcare team can better address and support the patients through the many HSCT complications. This not only requires physicians from nearly every specialty but also nurses from a wide variety of backgrounds, social workers, mental health specialists, pastoral care, nutritionists, and many others. As a team, we can better encompass treatment aimed at helping patients in all aspects of their care.

TABLE 64.1 Complications of hematopoietic stem cell transplant | ||

|---|---|---|

|

PHYSICAL

Graft-versus-Host Disease

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is one of the most common complications after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Acute GVHD is typically defined as a disease that occurs in the first 100 days after transplant and chronic is defined as a disease that occurs after 100 days (14).

It is generally recognized that a temporal distinction is rather arbitrary and that disease manifestations would be a more appropriate means to make the distinction between

acute and chronic GVHD as they appear to involve different immune cell subsets, involve different cytokine profiles, involve somewhat different host targets, and respond differently to treatment. Accordingly, the NIH Consensus Conference has suggested a more complex categorization of acute and chronic GVHD (15,16). In either case, acute and chronic GVHD have a significant impact on short- and longterm morbidity as well as mortality in patients undergoing HSCT. As a result of the physical and emotional aspects of the transplant process and development of GVHD, QOL in transplant survivors can be adversely affected. The strongest association between reduced QOL and impaired functional status following HSCT is the presence of chronic GVHD (17). For patients with acute GVHD, they had measureable declines in their QOL over the first 6 months after HSCT compared with those with no acute GVHD; however, this effect did not persist at 12 months after HSCT unless the patient developed chronic GVHD (18).

acute and chronic GVHD as they appear to involve different immune cell subsets, involve different cytokine profiles, involve somewhat different host targets, and respond differently to treatment. Accordingly, the NIH Consensus Conference has suggested a more complex categorization of acute and chronic GVHD (15,16). In either case, acute and chronic GVHD have a significant impact on short- and longterm morbidity as well as mortality in patients undergoing HSCT. As a result of the physical and emotional aspects of the transplant process and development of GVHD, QOL in transplant survivors can be adversely affected. The strongest association between reduced QOL and impaired functional status following HSCT is the presence of chronic GVHD (17). For patients with acute GVHD, they had measureable declines in their QOL over the first 6 months after HSCT compared with those with no acute GVHD; however, this effect did not persist at 12 months after HSCT unless the patient developed chronic GVHD (18).

Acute GVHD

Occurring at rates 10% to 80% depending on the study, underlying disease, prophylaxis regimens, and other factors, acute GVHD is the most frequent cause of mortality following allogeneic HSCT due to its clinical toxicity, requirement for intensive immunosuppressive management and associated infections (19,20,21). It generally develops within 2 to 8 weeks after marrow transplantation. The most common manifestation of acute GVHD is dermatological (21,22) which in most cases accompanies other manifestations in the liver or gastrointestinal tract but each can occur independently.

The rash of acute GVHD is most commonly maculopapular, but can also be morbilliform, or sometimes a confluent erythematous exanthema. It may be pruritic or painful and it may often involve the palms and soles which can help distinguish it from drug eruptions that are usually not in this location (23,24). It can be mild and affect <25% of the body but also can be severe, leading to whole body erythema, desquamation, bullae formation, and sloughing of the skin (25). Patients with severe skin GVHD have similar features and the need for similar treatments as those of severely burned patients. Hepatic GVHD is difficult to diagnose due to a lack of definitive testing and these patients have many other reasons to present with hepatic dysfunction (drug toxicity, TPN, infection, cholelithiasis, veno-occlusive disease, etc.). Gastrointestinal involvement can lead to nausea, anorexia, pain, and watery secretory diarrhea. In more severe cases, it

may lead to mucosal denudation causing bloody diarrhea, hemorrhage, protein losing enteropathy, or ileus (26).

may lead to mucosal denudation causing bloody diarrhea, hemorrhage, protein losing enteropathy, or ileus (26).

There have been many advances in the prevention of acute GVHD but currently immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, and anti-lymphocyte antibodies are the mainstay in the prevention of GVHD and can be used in conjunction with engineered grafts to decrease the incidence of GVHD (27). Ursodeoxycholic acid can be used for hepatic prophylaxis (28). T-cell depletion of the marrow using anti-T-cell antibodies is an effective way to reduce acute and chronic GVHD but can lead to a higher rate of relapse (29).

Initial treatment is with corticosteroids, with about 40% to 50% of patients responding (30). Patients not responding to corticosteroids are treated with salvage therapies such as antithymocyte globulin, interleukin 2 receptor antibodies, anti-CD 147 monoclonal antibody, tumor necrosis factor antibodies, mycophenolate mofetil, and extracorporeal photopheresis; however, there are no specific guidelines that are the standard of care (21,31). Many of these agents produce a response to the acute GVHD; however, the risk of infectious mortality remains high as the treatment of acute GVHD leads to further immunosuppression and thus infectious susceptibility.

As these patients can quickly become critically ill, it is important to provide immediate disease-based treatment as outlined above. In addition, organ-specific supportive measures are critically important. Specific therapies for the skin include the use of topical emollient therapy and meticulous wound care, with considerations for care in a burn unit when appropriate and possible. For gastrointestinal tract complications, bowel rest, hyperalimentation, and antimotility agents may be required. In cases of bloody diarrhea, transfusion support may be necessary. Octreotide may help control the secretory component of gastrointestinal GVHD (32). As the majority of patients with steroid-refractory GVHD have a high mortality due to infection (33), systematic monitoring and judicious use of antibiotics for prophylaxis against infectious pathogens are essential.

Chronic GVHD

Chronic GVHD affects 27% to 60% of patients receiving allogeneic transplants from sibling donors and 42% to 72% from those receiving transplants from unrelated donors (34,35). The median onset of chronic GVHD is 4 to 6 months after HSCT (36). The major risk factors for chronic GVHD are human leukocyte antigen disparity, increasing age, and preceding acute GVHD (37,38). Treatment of chronic GVHD is usually less aggressive than that of acute GVHD; however, most of the chronic GVHD patients require prolonged treatment lasting many months to years (20). In addition, combined with the stress of the existing diagnosis, the added stressor of developing chronic GVHD represents the most important cause of non-relapse mortality beyond 2 to 3 months after transplantation. This is usually due to its significant immune dysfunction and the resultant increased infectious susceptibility (21). Detailed grading systems have been developed by the NIH Consensus Conference to classify the severity of chronic GVHD which help predict outcomes (15,39). Generally, risk factors for worse prognosis are extensive skin involvement, progressive onset of chronic GVHD following acute GVHD, thrombocytopenia at diagnosis, and direct progression from acute GVHD (40).

First-line treatment for chronic GVHD is steroids, and just as in acute GVHD, approximately 50% of patients are steroid-refractory patients which is associated with a worse prognosis. Second-line initial treatments are calcineurin inhibitors, extracorporeal photopheresis, mTOR inhibitors, and mycophenolate mofetil. The assessment of effectiveness of treatment is at 8 to 12 weeks (39).

With all these complications and the resultant prolongation of illness, it is not surprising that the strongest association between reduced QOL and impaired functional status following HSCT is the presence of chronic GVHD (17). These patients continue to battle with the process and effects of HSCT. The individual symptoms discussed below lead to numerous physical and emotional disturbances that effect QOL and thus it is critical to aggressively support each patient through each symptom using innovative and creative solutions. Supportive care should include education, prevention of flares, infectious disease prophylaxis, physical and occupational therapy, nutrition, alleviation of chronic manifestations and effects of treatments, and promotion of coping mechanisms or resources to help patients deal with the psychosocial, sexual, and financial consequences of the disease (41). Below, we will address the skin, oral, ocular, and gynecological manifestations as these are key places where supportive care can aid in the overall care for the chronic GVHD patient.

Skin. The cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD are broad, but can be classified into three groups: lichen planuslike lesions, sclerotic skin manifestations, and poikilodermatous changes. Lichenoid chronic GVHD presents as an erythematous papular rash that resembles lichen planus; sclerodermatous GVHD may involve the dermis or muscle fascia leading to dermal fibrosis and fasciitis, while poikilodermatous skin changes appear as patches of mottled pigmentation and telangiectasias (23,25,34). All of these changes can lead to fragile skin with increased risk of erosions and ulceration or the skin can become thickened and tight with resultant detriment to the range of motion and poor woundhealing capacity. Any of these changes can lead to intense pruritus or pain. Hair loss and destruction of sweat glands are common; blistering may occur in severe cases. These symptoms are compounded by the patient’s perception of their further worsening appearance, especially if widespread.

Oral and topical steroids serve as the primary treatment for cutaneous chronic GVHD (34,36,42). Petrolatum-based emollients are helpful for those patients with xerotic skin. In addition, topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus), phototherapy, and extracorporeal photopheresis can be helpful. Oral anti-pruritic agents such as antihistamines and tricyclic antidepressants such as doxepin should be used with caution as they can worsen oral and ocular sicca symptoms. Topical hydrocortisone, pramoxine, menthol-based creams/lotions, doxepin cream, or colloidal

oatmeal powder bathtub soaks can also be used for short-term relief of intractable pruritus. For patients with thickened/tight skin and decreased range of motion, deep muscle/fascial massage is recommended, as well as daily stretching and referral to physical and/or occupational therapy. Surgical release can be considered in extreme cases. For patients with erosions and ulcerations, topical or oral antimicrobials, wound dressings, and debridement should all be considered. It is also important to instruct patients to take preventive measures such as avoidance of sun exposure, use of sunscreens (SPF > 20 with broad-spectrum UVA and UVB protections), and the use of protective clothing as there is an increased risk of skin cancer in patients with chronic GVHD (2,42,43,44,45).

oatmeal powder bathtub soaks can also be used for short-term relief of intractable pruritus. For patients with thickened/tight skin and decreased range of motion, deep muscle/fascial massage is recommended, as well as daily stretching and referral to physical and/or occupational therapy. Surgical release can be considered in extreme cases. For patients with erosions and ulcerations, topical or oral antimicrobials, wound dressings, and debridement should all be considered. It is also important to instruct patients to take preventive measures such as avoidance of sun exposure, use of sunscreens (SPF > 20 with broad-spectrum UVA and UVB protections), and the use of protective clothing as there is an increased risk of skin cancer in patients with chronic GVHD (2,42,43,44,45).

Oral. Almost 80% of patients diagnosed with chronic GVHD demonstrate some degree of oral involvement, making this one of the most common clinical manifestations of chronic GVHD. The clinical findings can include erythema, leukoplakia, lichenoid lesions, ulcers, mucosal atrophy, cicatricial changes, and xerostomia (44,45). These can range from very mild changes to severe ones that can be functionally debilitating and lead to a decreased QOL due to significant pain, weight loss, malnutrition, and the loss of the ability to enjoy food and the process of eating.

Similar to the treatment of skin chronic GVHD, topical high potency corticosteroids are often used for the treatment of oral chronic GVHD (46). Additionally, supportive interventions for patients with oral chronic GVHD include encouraging good oral hygiene and utilizing of topical anesthetic agents, such as viscous lidocaine, to reduce pain and facilitate oral intake. Patients with xerostomia may benefit from salivary stimulants (sugarless gum or candy), oral lubricants or saliva substitutes, and frequent water sipping. Cholinergic agonists to stimulate saliva production (e.g., pilocarpine and cevimeline) may be useful in patients in whom the use of these agents is not contraindicated. Xerostomia can increase the risk of tooth decay, so it is also important to encourage the use of topical fluorides (47). Advise patients to avoid mint-flavored toothpastes and whitening products, as these can further aggravate the oral mucosa.

Ocular. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is the most frequent presentation of chronic GVHD of the eye (42,48). Other eye chronic GVHD consequences are acute conjunctival inflammation and pseudomembranous and cicatricial conjunctivitis. These can lead to ocular irritation, dry eye syndrome, pain, or visual changes. Topical treatments include artificial tear liquids, ointments, slow dissolving hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, cyclosporine eye drops, cyclosporine eye patches/contacts, serum eye drops, and judicious use of topical steroid drops. Oral medications include cevimeline, pilocarpine, flaxseed oil, and doxycycline. Occlusive eye wear, warm compresses, humidified environments, or specialized contact lenses can also be used. Surgical interventions can also be considered (42,48,49).

Vulvar/Vaginal. Gynecological presentations of chronic GVHD are not as frequently studied as the other complications of chronic GVHD (50). However, the effects of chronic GVHD on the female reproductive tract can be difficult for women and thus it is important to ask about these issues, assess them, and treat them aggressively or refer to a physician that can do so. Symptoms can include dysuria, dryness, tenderness to touch, and dyspareunia. On examination, there may be erosions and fissures, introital stenosis, resorption of the labia minora, vaginal synechiae, or vaginal narrowing. Treatment includes the avoidance of mechanical and chemical irritants, the use of emollients such as lanolin cream applied to external genitalia, and water-based lubricants internally for the vagina. Short-term use of ultrahigh potency corticosteroid or topical calcineurin ointments can also be tried. In addition, topical and systemic estrogen or hormone treatment can be tried for patients that do not have contraindications. Dilators can be helpful in vaginal GVHD that leads to fibrotic vaginal scarring, and only in extreme cases, surgical interventions should be performed (42,43,50,51,52). Though they are limited in number, gynecologists with familiarity of GVHD are the best physicians to treat these patients.

PSYCHOLOGICAL

Psychological Effects

An important survey of 600 HSCT survivors was conducted in 2006 by the Bone Marrow Transplant Information Network, which found that 73% of respondents endorsed emotional/psychological health as the most significant issue facing them following transplantation (53). Studies also have shown that biopsychosocial models will better predict cancer treatment-related pain and distress than a strictly biomedical model (54). The transplant process can be psychologically devastating which consequently can be destructive in a patient’s personal and family life. Patients that undergo this process have many sources of stress as they are faced with many questions about the process and how they will fare in comparison to the statistics they are given. There undoubtedly will be fear: fear that the transplant will not cure, fear that it might kill, fear of pain, fear of the complications, fear that they will never be the same, fear for their family, etc. Even if they are cured of the disease they had, studies show that HSCT patients have a sense of feeling different from “normal people” despite having physical recovery (55).

These patients have been forever changed by their experience of illness and all the psychosocial changes a prolonged illness can bring. Unfortunately, in 2008, The Institute of Medicine report identified that meeting psychosocial needs of patients and family is the exception rather than the common occurrence in the current healthcare climate (56). This is not an unsurprising finding as the psychological and social issues can be more challenging for the healthcare team than the medical issues (57). We hope that this improves in the future but this will require an increased awareness of these issues as well as a dedicated approach to identifying, recognizing, and treating the reality of the psychosocial distress that endangers these patients. Attention to psychosocial

factors in cancer patients before transplantation is important because social support, optimism, and self-efficacy measured prior to HSCT predicted health-related QOL 1 year posttransplantation (58). Not surprisingly, patients with previous psychiatric morbidity such as those patients with anxiety or depression are at risk for poorer health outcomes, longer length of hospital stay, and higher mortality (59,60,61,62,63).

factors in cancer patients before transplantation is important because social support, optimism, and self-efficacy measured prior to HSCT predicted health-related QOL 1 year posttransplantation (58). Not surprisingly, patients with previous psychiatric morbidity such as those patients with anxiety or depression are at risk for poorer health outcomes, longer length of hospital stay, and higher mortality (59,60,61,62,63).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree