Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations of the Head and Neck

James Y. Suen

Gresham T. Richter

INTRODUCTION

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations (VMs) are not cancers, but they occur frequently in the head and neck region and commonly present to the head and neck surgeon. These can be very destructive and even life threatening. The head and neck surgeon needs to know how to identify and manage these uncommon but complex benign vascular lesions. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that many vascular malformations exhibit behavior similar to low-grade malignancies.

The treatment of vascular anomalies should be performed by an experienced team of specialists, consisting of surgeons, diagnostic radiologists, interventional radiologists, dermatologists, pediatricians, medical oncologists, and other specialties. Because of the psychological impact on these patients, it is important to understand and address this issue as well. Vascular anomalies may cause aesthetic complications, functional disorders, physical disabilities, and pain. These patients can become quite withdrawn and depressed, and these aspects should be similarly addressed by the multidisciplinary team, including psychologists, to improve quality of life and patient satisfaction.

Many of the VMs cannot be cured but can only be controlled. It is important to convey full understanding of this concept, when counseling patients and their families at the onset of diagnosis in order to set appropriate levels of expectation from treatment. Frequently multiple treatments are required to control vascular anomalies, which may require lifelong medical and psychological care.

Classification

Vascular anomalies are divided into vascular tumors, of which infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are by far the most common type, and VMs. The natural history of these two groups is quite different. These lesions are also fundamentally distinct in their radiographic and histologic appearances as well as their biologic behavior and prognosis. All vascular anomalies are best classified using the scheme introduced by Muliken and Glowaki and recently codified by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. In the past, VMs were erroneously called hemangiomas, which led to fundamental errors in management and patient outcomes.

IHs are vascular tumors composed of rapidly dividing hematogenous endothelial cells. These lesions will be noticed during the first few months of life and can grow rapidly until about 1 year of age. At this age, IHs begin to regress or involute. Over several years, many IHs will eventually disappear but may leave evidence, or sequelae, of their early presence. True IHs are histologically similar to placenta and may be the result of early stem cell progenitors from this tissue. The clinical similarities between IHs and placenta in their growth patterns are convincing. Placenta will grow for 9 months and involute when a baby is born—IHs grow for about 1 year and then begin to involute and eventually disappear.

VMs are anomalous vascular channels lined by a single endothelium that are usually present at birth. VMs are classified based upon their blood vessel type and can be seen early in life. Depending on the depth of the VMs, they may not appear obvious until later in life. They do not involute and will continue to slowly grow with ultimately destructive and life-threatening consequences. This distinction between IH and VM is extremely important to understand. Later in this chapter, the criteria for diagnosis of each type of vascular malformation will be addressed. Table 37.1 lists the classification of vascular anomalies.

HEMANGIOMAS

IHs are composed of proliferating immature endothelial cells that express histologic markers found on placental blood vessels as reported by North et al.1 These are the most common tumor of infancy and are present in ˜5% of the population. They occur more frequently in infants from mothers with early trimester bleeding, preeclampsia, and placental anomalies.2 IHs are rarely noted at birth, but commonly a macular erythema area of the skin is noted in the first 6 weeks of life and then a rapid growth is usually noted. These lesions present in the head and neck region in over 60% of cases. Most IHs grow within the first 3 months of life and continue to grow up to 1 year of age and may be very extensive. After 1 year of age, IHs will go into a quiescent phase and began to involute and eventually resolve. Most will involute completely by 7 years of age. This natural history is important to differentiate IHs from other congenital vascular lesions and will help to guide management decisions.

IHs can present as focal or segmental lesions involving multiple areas. They are also characterized as superficial, deep, or compound. It is rare for a focal IH to involve muscle or penetrate beyond subcutaneous fat. However, an IH involving the parotid gland can involve the gland itself.

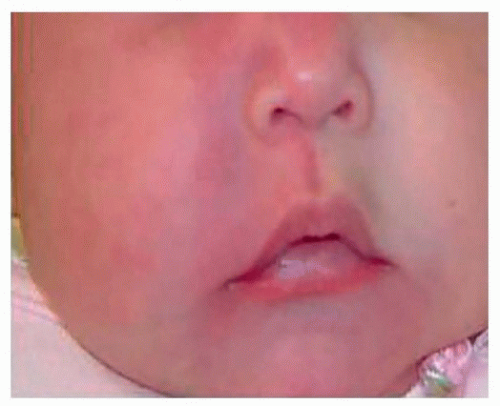

When IHs involve the lip, eyelids, orbit, and nose, or subglottic region, they may lead to significant functional and/or aesthetic problems during the rapid proliferation phase (Fig. 37.1A-C).

Infants with five or more focal IHs may also have hepatic involvement and should undergo abdominal ultrasound. Segmental IHs are usually more complex and in the head and neck will follow a trigeminal nerve distribution. They are diffuse and compound and maintain irregular borders. It is common to see more than one facial subunit involved (Fig. 37.2).

They commonly penetrate into deep fascial planes of the head and neck. IHs involving the beard distribution are those most commonly described. These usually involve the lower lip, chin, neck, and preauricular areas, and ulcerations are frequently present. As many as 60% of IHs with a segmental beard distribution will involve the subglottis and require airway endoscopy.3 Patients with segmentally distributed IHs should be evaluated for PHACES syndrome (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial lesions, cardiac abnormalities, eye abnormalities, and sternal clefts).

They commonly penetrate into deep fascial planes of the head and neck. IHs involving the beard distribution are those most commonly described. These usually involve the lower lip, chin, neck, and preauricular areas, and ulcerations are frequently present. As many as 60% of IHs with a segmental beard distribution will involve the subglottis and require airway endoscopy.3 Patients with segmentally distributed IHs should be evaluated for PHACES syndrome (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial lesions, cardiac abnormalities, eye abnormalities, and sternal clefts).

Table 37.1 ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 37.1. A: Ulcerative hemangioma of the lower lip. B: Paranasal hemangioma. C: Segmental hemangioma involving the temple area and the orbit causing visual obstruction. |

The diagnosis of IHs is primarily clinical. They are not usually noticed at birth, and when the child is between 1 and 3 months old, these lesions will begin growing and after 1 year, they will begin to involute. Biopsies are not usually necessary and scans are not usually indicated unless there is a concern for the PHACES syndrome.

The management of IHs has improved significantly in recent years. Because of their natural involution, IHs were historically managed with observation only. Even though they resolve spontaneously, they can cause significant functional and disfiguring sequelae. Most problematic events from IHs will occur during the proliferative phase and may include ulceration, bleeding, pain, disturbance of vision, airway compromise, and feeding difficulties. The late sequelae will include scarring, telangiectasias, and fibrofatty residuum.

The treatment of IHs may involve surgical excision, laser therapy, topical therapy, intralesional corticosteroids, systemic corticosteroids, systemic β-blockers, and vincristine chemotherapy. If an infant has a focal hemangioma, which is primarily deep, the lesion can typically be observed unless ulceration or bleeding occurs. For the superficial focal lesions, laser therapy or surgery can be used to control the IH. For the problematic hemangiomas, β-blockers have been found to be effective in over 95% of the cases with rapid involution. The most common dose of β-blockers has been 2 mg/kg/day in divided doses two to three times daily.4 During the involution phase, surgical excision can give excellent results and prevent late sequelae.

VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

As mentioned previously, VMs are very different from IHs. They do not involute and will continue to progress throughout life. They may have rapid growth spurts at different times of life. Our research has shown that many VMs have progesterone receptors5 and this is associated with growth spurts during puberty, use of oral contraceptives, and pregnancy. We commonly see patients

who did not notice their malformation until these events occurred. There are also unknown causes for growth spurts, which have not been identified yet. The destructive and life-threatening events that occur from many VMs will be illustrated.

who did not notice their malformation until these events occurred. There are also unknown causes for growth spurts, which have not been identified yet. The destructive and life-threatening events that occur from many VMs will be illustrated.

Capillary/Venular Malformations

Capillary/venular malformations (CM) are histologically composed of congenital ectasia of thin-walled, small-caliber capillaries and veins of the skin. The simplest presentation of a capillary malformation is known as a nevus flammeus or “port-wine stain” (PWS). They occur in 0.3% of newborns and are visible at birth. They commonly appear as sharply demarcated, homogeneous, erythematous macules, typically located on the face or neck. They can also involve the mucosa of the upper aerodigestive track when the overlying skin is involved, such as the lip and cheek areas. If left untreated, CMs will darken in color and develop nodular changes. Hyperplasia of the underlying soft tissues commonly occurs (Fig. 37.3).

Capillary malformations usually occur spontaneously within a population and are the most common cutaneous vascular malformation seen. There is not an identifiable genetic component, although a subclass of CMs associated with arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) has been identified as having autosomal dominant transmission and associated mutations in the RASA1 gene.6

Approximately 75% of capillary malformations are located in the head and neck. Extracutaneous involvement can also occur and affect the central nervous system, eyes, or other organs.

Capillary malformations may be an isolated cutaneous lesion or a syndrome-related lesion. Parkes-Weber syndrome presents as a cutaneous capillary malformation with hypertrophy of limbs and can have arteriovenous fistulas and congenital varicose veins.7 Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is associated with three distinct features: the presence of a PWS, soft tissue or bony hypertrophy (or both) of the extremities, and varicose veins or venous malformations. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of any two of the three features.8

The treatment for capillary malformations is primarily performed using lasers. If left untreated, the affected area of skin darkens and hypertrophies to cause thick and nodular lesions that lead to disfigurement and often subsequent psychological disturbance. The pulsed-dye laser (PDL) has been the most commonly used laser for cutaneous involvement of PWSs. It commonly requires multiple, frequent treatments and may lighten and maintain a sustained response for several years after PDL therapy. The intense pulsed light (IPL) laser is also shown to be effective for PWSs.

Only about 10% of patients with PWS can be cured with laser therapy, and these are usually those individuals with small superficial lesions. Treatment during infancy can lighten the PWS after an average of three or four sessions.9 It is rare to see skin complications from these two lasers.

Older patients with very thick and nodular PWSs may require surgery to remove the most disfiguring and symptomatic lesions (Fig. 37.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree