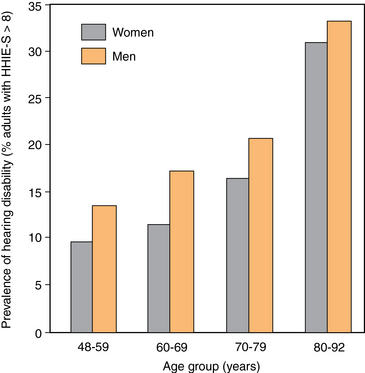

25 Barriers to the Evaluation and Treatment of Hearing Loss Risk Factors and Pathophysiology Differential Diagnosis and Assessment Detection and Evaluation of Hearing Loss Management of Hearing Impairment Counseling Older Adults about Hearing Health Services Enhancing Communication with the Hearing Impaired Hearing Aid Use and Effectiveness Insurance Coverage for Hearing Aids Managing Feedback in Hearing Aids Audiologic Rehabilitation Courses Indications for Otolaryngology Referral Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify effects of aging on the auditory system. • Describe the psychosocial and functional consequences of hearing loss. • Interpret common tests used to evaluate hearing impairment and disability. • Distinguish presbycusis from other forms of hearing loss. • Discuss the differential diagnosis for adult hearing impairment. • List appropriate indications for audiology and otolaryngology referrals. Hearing loss is common in older adults and has serious psychosocial and functional consequences. It affects one third of individuals 65 years or older and ranks as the third most common chronic disease in that age category. Hearing impairment rises geometrically with age from 16% at age 60, 32% at age 70, and 64% at age 80. The prevalence of hearing disability also rises with age (Figure 25-1). Functional deficits associated with hearing loss include diminished ability to recognize speech amid background noise and to locate and identify sounds that may have an important warning or alarm significance. The communication difficulties experienced by the hearing impaired also affect other people in their environment such as family members and coworkers. Hearing loss is associated with depression, social isolation, and poor self-esteem, as well as cognitive decline. Figure 25-1 Prevalence of hearing disability (Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly–Screening Version [HHIE-S] score >8) by age and gender. (Modified from Wiley T, et al. Self-reported hearing handicap and audiometric measures in older adults. J Am Acad Audiol 2000;11:67-75.) Despite the importance of hearing function in everyday life, hearing loss is often a poorly recognized and undertreated problem. The insidious onset and progression of age-related hearing loss (ARHL) likely contributes to its under-recognition. Although 26.7 million U.S. adults aged 50 years or older have clinically significant hearing loss, fewer than 15% use hearing aids.1 In the United States, only about 40% of people with moderate to severe ARHL own hearing aids; that percentage drops to 10% among persons with mild ARHL.2 The subtle presentation of ARHL is rarely a call to action for either the afflicted person or his or her doctor. In the mild to moderate stages, ARHL is often characterized by the inability to understand words rather than the inability to hear, and the common refrain of “My hearing is fine. You’re just mumbling.” The functional consequences of hearing disability, however, should not be underestimated. When affected individuals do become aware of their hearing loss, initially they may try to compensate and conceal it, but symptoms eventually give their secret away. Persons wait on average 7 to 10 years between signs of hearing loss and audiologic consultation.3 Affected persons may not be aware of the functional deficits or know what they are missing. Older persons who have ARHL but do not pursue hearing aids demonstrate less problem awareness on questionnaires of self-perceived hearing disability and have a greater tendency to deny communication problems. The high cost of hearing aids is an additional barrier to treatment for many older Americans. Usual aging changes in the auditory system contribute to diminished hearing performance among older adults (Box 25-1). Prior noise exposure, middle ear disease, and vascular disease affect the progression of ARHL. Longitudinal studies demonstrate that hearing declines gradually in 97% of the population as evidenced by diminished pure-tone threshold sensitivities with age. Individuals under 55 years of age typically lose hearing at a rate of 3 dB per decade, and those over 55 years at a rate of 9 dB per decade.4 The ability to understand speech in a backdrop of competing conversations begins to deteriorate slowly in the fourth decade of life, and accelerates after the seventh decade. As adults age, it also becomes increasingly difficult for them to understand speech that is rapid, poorly transmitted, or mispronounced. Hearing loss can result from diseases of the auricle, external auditory canal, middle ear, inner ear, or central auditory pathways. Diseases of the inner ear or eighth nerve cause sensorineural hearing loss, whereas diseases of the auricle, external auditory canal, or middle ear generally cause conductive hearing loss. Mixed loss refers to a combination of conductive and sensorineural loss. Central auditory processing dysfunction is a major factor affecting speech perception in the seventh decade and beyond. Attention should be paid to memory function also because memory impairment affects central auditory ability.5 Box 25-2 lists the differential diagnosis.

Hearing impairment

Prevalence and impact

Barriers to the evaluation and treatment of hearing loss

Aging changes

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine