CLINICAL PEARLS

“Loud talkers” typically suffer from sensorineural hearing loss, whereas “soft talkers” have conductive hearing loss.

Functional hearing deficits can be identified in the examination room by creating background noise while looking away from the patient and asking a few simple questions.

Patients complaining that people always yell may have a narrow range between audible and uncomfortably loud sound.

Consider magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast when a patient presents with rapidly progressing unilateral sensorineural hearing loss or hearing loss associated with vertigo because these symptoms may be due to a vestibular schwannoma.

High-resolution computed tomography scan effectively visualizes some conditions of the middle ear causing conductive hearing loss such as cholesteatoma or otosclerosis.

Hearing aids make speech louder but not clearer.

Aural/hearing rehabilitation programs minimize the effects of hearing impairment for patients using or refusing hearing aids.

Ninety percent of patients older than 80 years cope with difficulty in hearing conversations, instructions, or sounds that enrich, orient, or protect them. Hearing loss is in fact the third most common chronic condition of aging, following arthritis and hypertension.

1 The condition is more than a minor inconvenience. It contributes to impaired cognitive function, significant social and emotional handicap, and loss of independence.

This chapter reviews the etiology of hearing loss resulting from environmental insults and physiologic changes in the ear in response to aging (i.e., presbycusis or impaired audition in aging). Practical techniques for detecting hearing loss in the clinician’s office and interpreting common diagnostic tests typically performed by audiologists are presented in conjunction with strategies for treatment, rehabilitation, and selection of assistive devices from the array of options on the market. Also included is a discussion of tinnitus, a frustrating hearing condition for both patients and their clinicians and its companion, vertigo.

HEARING AND AGING

A common prop in caricatures of frail, feisty, wrinkled, stooped old folks is a ram’s horn strategically held next to the ear to capture sound. The image reflects behaviors that are symptomatic of impaired audition: Turning up the volume on the television or radio, speaking loudly, misinterpreting words, or disengaging from group discussions. However, hearing decline begins in the fourth decade. The extent and causes of hearing loss vary considerably across individuals; however, large cohort studies in Framingham, Wisconsin, Baltimore, Venice, Gothenburg (Germany), Denmark, and the United Kingdom consistently document the prevalence of the problem. Overall prevalence of hearing loss in a cohort of 3,753 persons aged between 48 and 92 years in the Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, study was estimated to be 45.9%.

2 Hearing declines at the rate of 0.5 to 0.7 dB per year for highpitched sounds (i.e., frequencies of 2 to 4 kHz). This rate of decline quadruples in the seventh decade, particularly among men. Although this may vindicate those accused of “wife deafness,” the gender gap virtually disappears by the ninth decade. According to Schuknecht,

3 there are multiple patterns, and therefore multiple underlying structural patterns, of age-related hearing loss, including sensory, neural, strial, and cochlear-conductive forms of presbycusis.

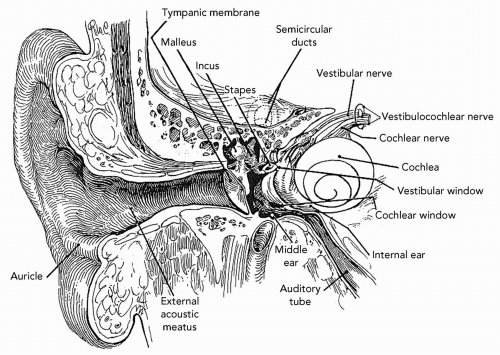

Human hearing translates vibrations into identifiable sounds ranging from the subtle drip of a leaky faucet to the startling clap of nearby thunder. The brain uses the difference in timing and level of signals arriving from a pair of ears to reliably locate the source of sound. Mechanical sound waves are captured by the saucer-shaped outer ear and travel through the auditory canal to the flexible eardrum (tympanic membrane [TM]) (see

Fig. 12.1). The resulting vibration is transmitted to the first of three linked bones or ossicles in the middle ear: The malleus, incus, and stapes. The stapes, resembling a saddle, inserts into the oval window of the inner ear’s cochlea. Because this membrane is much smaller than the eardrum and because the ossicles multiply incoming forces by their combined mechanical advantage, the pressure exerted on the cochlea is approximately 20 times stronger than that on the TM.

4 The cochlea, bearing a striking resemblance to the shell of the chambered nautilus, is filled with fluid. Specialized hair cells in the inner ear (cochlea), organ of Corti, pick up the transmitted cadence, opening up ion channels when the hairs (stereocilia) bend and leading to an intracellular depolarization. This completes the conversion of mechanical energy to electrical energy and leads to the release of neurotransmitters. The auditory branch of the eighth cranial nerve projects onto the cochlear nuclei, through the auditory brainstem to the medial geniculate body of the metathalamus, and, finally, to the primary auditory cortex of the temporal lobe. The cochlea also intercepts vibrations directly from surrounding bone, which serves as the basis for bone-conduction thresholds used audiometrically.

With age, alterations in the peripheral receptive organ contribute to presbycusis. Elasticity diminishes in the cartilage of the outer ear. Reduced numbers of active sebaceous glands produce drier and less viscous cerumen that is prone to obstruct the external auditory canal. Mechanical transmission of sound is affected by decreased elasticity, thinning of the TM, and calcification of the

joints between the middle ear ossicles. The inner ear’s organ of Corti, however, is most susceptible to age-related changes. The stria vascularis may atrophy. This network of endolymph-secreting capillaries generates a resting potential (called the

endolymphatic potential) that sensitizes the hair cells in the cochlea.

5 Hair cell loss, most severe in the basal or high-frequency region of the cochlea, is responsible for the decline in pure-tone hearing in conjunction with loss of ganglion cells and reduction in fibers in the cochlear nerve. Hearing is also contingent on timely and accurate interpretation of information from the environment. Processing information in the temporal lobe may be affected by reduction in neuron number, size, or dendritic arborization.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hearing deficits are categorized as conductive, sensorineural, or retrocochlear. A conductive hearing loss locates the problem to the middle or external ear. A sensorineural loss stems from inner ear structures (primarily the stria vascularis and cochlear hair cells). A retrocochlear loss involves portions of the auditory system that involve the eighth cranial nerve or central auditory nervous system. Once localized, the differential diagnosis includes age-related structural changes (i.e., impacted cerumen, tympanosclerosis, cochlear hair cell loss), infections, tumors, trauma, noise or other toxic exposures, genetic traits and congenital malformations. Tinnitus, often associated with hearing loss, is a troubling condition caused by the perception of sounds without an external source.

Table 12.1 lists some conditions that are associated with hearing difficulty.

PRESBYCUSIS

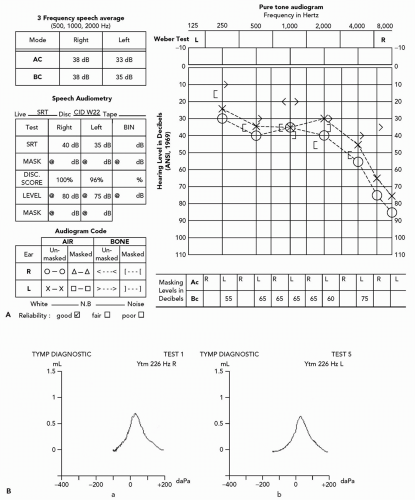

This woman would be a good candidate for a hearing aid because her hearing loss in the lower frequencies is sufficient to make it difficult to hear speech at conversational levels and her speech discrimination in quiet is excellent.

Screening

It has been reported that approximately 20% of physicians routinely screen their older patients for hearing loss.

6 Do not assume that the patient who easily converses face-to-face in a quiet examination room is free of significant hearing impairment. A more accurate picture is obtained by asking about hearing in the context of common situations. “Do you have difficulty hearing phone conversations?” “Is it difficult to hear when you are in a restaurant?” “Do you need to turn up the volume on the radio and television or does your family comment on your preferred listening volume?” Although patients are frequently accompanied by a spouse or child, resist the temptation to direct questions to them in lieu of the patient with an obvious hearing loss. Speaking directly to the patient promotes self-esteem, conveys respect, and demonstrates effective techniques for communicating with hearing-impaired listeners (e.g., maintain good eye contact, speak slowly without exaggerated lip movements or facial expressions, and rephrase rather than repeat misunderstood statements).

7The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE), developed by Ventry and Weinstein (1982), identifies individuals with sufficient handicap to warrant professional follow-up. Research demonstrated adequate sensitivity and specificity for a self-administered ten-question version that can be completed in the office waiting room.

8,

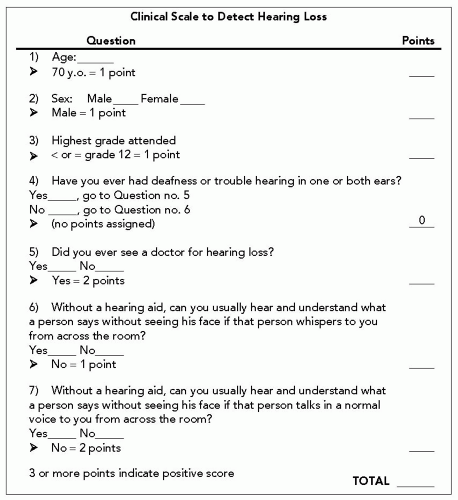

9 More recently, data from the 1971 to 1975 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and two established criteria for defining hearing loss (Ventry and Weinstein Scale and the High-Frequency Pure-Tone Average [PTA] Scale) were the basis for a seven-item questionnaire incorporating sociodemographic characteristics, as well as specific hearing loss questions (see

Fig. 12.3). Scoring 3 of a possible 8 points is considered positive (sensitivity 80.1%; specificity 80.1%; odds ratio of 16.2 with 95% confidence interval).

10The medical, family, and social history are aimed at identifying causes of hearing difficulty. Past or present use of aminoglycoside antibiotics, quinine derivatives, loop diuretics such as furosemide or ethacrynic acid, and salicylates may suggest otoxicity contributing to hearing loss. A past history of chronic otitis media or mastoiditis may be accompanied by hearing loss. Although a commonly held belief is that hypothyroidism, diabetes, or multiple sclerosis is linked as well, the incidence among patients with these conditions does not appear different than that of the general population. Vocational, recreational, or situational sound exposure should be ascertained. The loud explosions of war, for example,

subjected many World War II veterans, now elderly, to noise and sound pressures capable of inducing acoustic trauma. Family history of hearing loss is commonly associated with age-related hearing loss.

Physical Examination

The clinical examination begins with listening to the patient’s speaking voice. A monotonous tone or inappropriate volume may suggest hearing loss.

5 Loud talkers may have a sensorineural problem, whereas soft talkers more often have a conductive problem. Create background noise and negate lipreading by turning on a radio and turning away from the patient while asking a few questions. These maneuvers are effective in demonstrating hearing deficits that may not be reflected in an audiogram obtained under soundproofed laboratory conditions.

Inspection of the auditory canal for obstructing cerumen is essential. Removal of the material is a prerequisite for completing the examination and is often therapeutic. Lowpressure irrigation with warm water is the preferred technique. Application of hydrogen peroxide or products such as trolamine polypeptide oleate (Cerumenex) or carbamide peroxide (Debrox) for 3 days facilitates the procedure.

Middle ear landmarks may appear more pronounced when viewed through the more translucent TM of an elderly patient. White patches indicative of healed perforations, dullness from fibrosis, or redness visible behind the TM, with or without perforation (i.e., cholesteatoma), are among chronic findings that often herald hearing difficulty (see

Table 12.2). These findings may interfere with the transmission of sound waves, causing a conductive hearing loss (see in the subsequent text).

Simple tests and maneuvers aid diagnosis in the examination room. Although individually subjective, collectively they accurately localize hearing loss and distinguish between conductive and sensorineural causes:

Whispered Voice:

The examiner places a finger in one ear canal and gently moves it to mask hearing, simultaneously testing hearing in the other ear by whispering one- and two-syllable words while standing 30 to 60 cm away. The patients should correctly repeat at least 50% of the softly whispered words.

Ticking Watch:

Mask hearing in one ear while moving a nonelectric watch toward the test ear and record the distance where the tick becomes audible. Compare results to those in normal patients.

Tuning Fork Tests:

Weber:

Place a vibrating tuning fork (usually a 128 or 256 Hz frequency) on the midline of the patient’s head and ask where sound is best heard. Midline is the normal response. Sound lateralizes to the ear with poorer hearing in a conductive hearing loss or to the better ear if the etiology is sensorineural.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access