In order to monitor and report on the incidence of HAIs, the U.S. NHSN collects data reported from various healthcare institutions. The monitoring of nosocomial infections initially started in 1970 with the establishment of the National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance system, which took routinely reported data from a select group of hospitals.

27 With the publication of the seminal “To Err is Human” from the Institute of Medicine in 1999, which brought attention to the issue of patient safety, changes have been made to prevent errors that lead to patient harm. In 2014, the CMS developed a method to decrease reimbursements for adverse events the hospital can prevent by following evidence-based guidelines. With various stakeholder interest in decreasing CLABSIs, there has been a significant decrease in infection rates from 2001 to 2011.

2 In the last several years, the NHSN has changed how CLABSIs are reported nationally, from rates per 1000 central line days to standardized infection ratios (SIRs, See also

Chapter 2 on Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections).

28 This change was made as comparing rates did not necessarily reflect the differences between hospitals or hospital locations as they may serve a different patient population and made it more difficult to calculate the overall performance of a facility. Additionally, by converting to SIRs, adjustments can be made to account to some degree for those populations at increased risk of infections. According to the NHSN, the SIRs for CLABSI in acute care hospitals are adjusted based on the location where the infection is acquired, the number of beds in the hospital, and whether or not the hospital is affiliated with a medical school.

28 According to the most recent NHSN data from 2017, the baseline national U.S. SIR is 0.81, with a 19% decrease in CLABSIs from 2016 to 2019, but 9% of the hospitals had CLABSI burdens that were significantly worse than the national SIR.

29

Catheter-Related Risk Factors

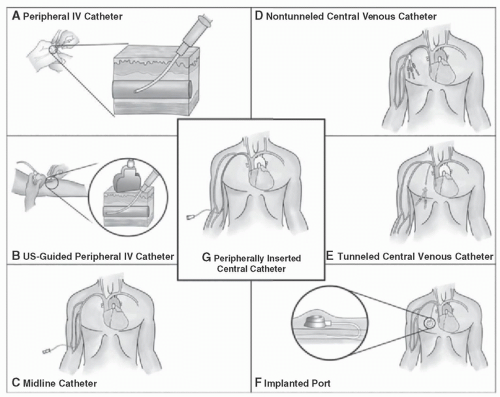

As opposed to patient-related risk factors, catheter-related risk factors are in general modifiable but vary in the level of risk involved. Peripheral IVs (PIVs) are the most common

intravascular device but have a relatively lower risk of bloodstream infections compared to other intravascular devices.

26 However, given that PIV devices are used in such far greater numbers compared to other vascular access devices, like CVCs, the rate of bloodstream infections likely approaches that of CVCs.

26,35 The risk of infection from peripheral venous catheters largely stems from catheter dwell time.

36 Additionally, thrombophlebitis, a known noninfectious complication of PIV insertion, may increase risk for bloodstream infections.

36,37 Recent work has shown that PIVs can serve as a source for

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and are likely largely unrecognized, and the use of PIV bundles may reduce the incidence of bloodstream infections.

37,38Midlines catheters and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are utilized for continual venous access in patients who extend beyond the hospitalized setting. These forms of vascular access are not without risk. Retrospective comparison between these two catheter types noted that midline catheters were more likely to have complications compared to PICCs, but these complications were often non-life threatening. Overall, data are unclear if the overall safety profile of midlines compared to PICC is better. PICC complications are often thought to be more serious, including bacteremia.

39 The risk of developing a CLABSI in patients with PICCs has been associated with the number of catheter lumens, length of hospital stay, and use of the catheter for chemotherapy.

13,40 Within specific patient populations (eg, the acute surgical patient population), PICCs and CVCs have not been shown to have an appreciable difference in infectious complications.

41,42Short-term Central Venous Catheters CVCs account for the majority of CLABSIs.

43 The following factors have been associated with an increased risk for CLABSI: prolonged hospitalization, prolonged duration of catheterization, heavy microbial colonization at the insertion site or catheter hub, neutropenia, the use of total parental nutrition, excessive manipulation of the catheter and the number of catheters inserted.

44,45 Data regarding the number of lumens and an increased risk of infection are mixed, with a meta-analysis showing a slight increased risk with multilumen central lines that diminishes when higher-quality studies that control for patient risk factors are examined; however, a more recent prospective study noted that increasing catheter lumens were an independent risk factor for CLABSI.

46,47 In a multicenter randomized controlled trial of CVC insertion sites, subclavian catheterization was associated with the lowest risk of bloodstream infections and symptomatic thrombosis but higher rates of pneumothorax.

48 Femoral catheters have been found to have higher rates of infection and thrombosis compared to subclavian and internal jugular catheters, though this may be mitigated if the catheter indwelling time is 4 days or less.

49,50,51 Though data can be mixed, avoidance of femoral site catheter placement and removal of emergently placed lines are frequently part of CLABSI bundles with the goal of reducing CLABSI risk.

52 Routine replacement of central lines is not recommended and likely only increases the risk of mechanical complication with no reduction in CLABSI risk.

53

Long-term Central Venous Catheters There are fundamental differences between infection rates and risk between short- and long-term catheters. The average infection rate for long-term CVCs ranges from 0.1 to 1.2 to 1.5 episodes per 1000 catheter-days, much less than that noted in short-term CVCs, which ranges from 1.2 to 2.9 per 1000 catheter days.

26 The data comparing CLABSI rates between long-term catheters and ports in a prospective randomized study of 100 cancer patients found no difference in infection rates between the two catheter types.

54 However, an observational study compared tunneled cuffed silicone catheters, PICCs, and ports, and identified an increased rate of catheter infections in tunneled cuffed silicone catheters compared to PICCs and ports. Patients with ports had almost no catheter infections in this study.

55 Additional comparison studies have noted that there is an overall decreased likelihood of infectious complications with ports versus other long-term catheter types.

56,57 Studies comparing the infection risk of other types of long-term catheters are mixed. In a prospective randomized study of 212 patients, no difference in infections rates was noted between patients with tunneled and nontunneled subclavian CVCs.

58 Additionally, another study of 84 patients found no difference in infection rates when comparing cuffed and noncuffed CVCs.

59

In looking at factors that increase bloodstream infections in long-term CVCs: age >65, cancer type, previous bloodstream infection, increased number of catheter lumens, multiple catheter manipulations, neutropenia, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and receipt of total parental nutrition have all been noted in clinical studies to be associated with increased risk.

60,61,62,63,64

Institution-Related Risk Factors

As mentioned previously, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses risk adjustment though the SIR to compare CLABSI rates across hospitals. Initially, only adjustment by type of intensive care unit (ICU) was included in the risk model, but in 2017, hospital size by beds and medical school affiliation were added.

65 Notably, there has been some controversy in the decision to include these criteria in the SIR calculation. A study found no association of medical school affiliation or hospital size with risk adjustment, but rather the use of patient comorbidities showed better discrimination between facilities.

34 The effect of staffing on CLABSI risk has shown mixed results with no significance noted between nursing and physician staffing and HAIs, but did find an increase in HAI rates with increased use of nonpermanent staff and mixed results with increased infection control personnel staffing.

66 The geographic location (ie, hospital unit) where the central line is placed has been associated with an increased risk of CLABSI. Placing a central line in an emergency room or an ICU has been associated with increased CLABSIs, but this likely reflects the patient who is in urgent need of vascular access, as well as more comorbidities with these patients.

67 While central lines placed in the ICU are associated with an increased risk for CLABSI, CLABSI rates outside ICUs have been assumed to be similar to those within ICU.

3 This is controversial as there have been data to show the rates have been higher, and there has been less research on the rates and prevention of CLABSIs in non-ICU settings.

2,68