Health Services: Introduction

Geriatrics can be thought of as the intersection of chronic disease care and gerontology. The latter refers largely to the contents of this book: the syndromes associated with aging, the atypical presentations of disease, and the difficulties of managing multiple, simultaneous, interactive problems. Health care for older persons consists largely of addressing the problems associated with multiple chronic illnesses. However, medical care continues to be practiced as though it consisted of a series of discrete encounters. What is needed is a systematic approach to chronic care that encourages clinicians to recognize the overall course expected for each patient and to manage treatment within those parameters. Chapter 4 traces a number of strategies designed to improve the management of chronic disease.

Several initiatives are under way that may help to address this dilemma. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act specifically addresses attention to transitions for patients discharged from hospitals. Payments for rehospitalizations are denied, and penalties for excessive rates are levied. The accountable care organization concept calls for better integration of hospital care, primary care, postacute care (PAC), and nursing home care. It may extend to recognizing the need for better social integration as well. The health care home effort to incent practices for more comprehensive care represents a step in this direction.

Care for frail older persons has been impeded by an artificial dichotomy between medical and social interventions. This separation has been enhanced by the funding policies, such as the auspices of Medicare and Medicaid, but it also reflects the philosophies of the dominant professions. A prerequisite for effective coordination is shared goals. Until the differences in goals are reconciled, there is little hope for integrated care. Medical practice has been driven by what may be termed a therapeutic model. The basic expectation from medical care is that it will make a difference. The difference may not always be reflected in an improvement in the patient’s status. Indeed, for many chronically ill patients, decline is inevitable, but good care should at least delay the rate of that decline. Because many patients do get worse over time, it may be difficult for clinicians to see the effects of their care. The invisibility of this benefit makes it particularly hard to create a strong case for investing in such care.

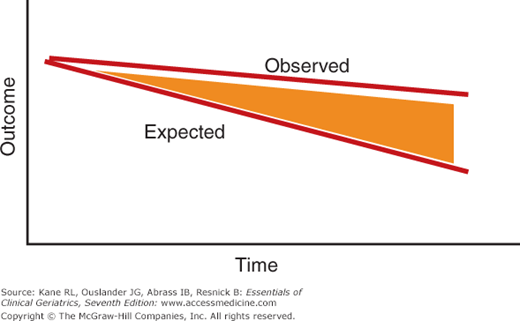

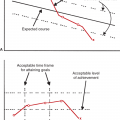

Appreciating the benefits of good care in the context of decline in function over time may require a comparison between what happens and what would have occurred in the absence of that care. In effect, the yield from good care is the difference between what is observed and what is reasonable to expect; but without the expected value, the benefit may be hard to appreciate. Figure 15-1 (which also appears in Chapter 4) provides a theoretical model of these two curves. Both trajectories show decline, but the slope associated with better care is less acute. The area between them represents the effects of good care. Unfortunately, that benefit is invisible unless specific steps are taken to demonstrate the difference between the observed and expected course. Appreciating the need to make this benefit visible is essential to make the political and social case for a greater investment in chronic disease and long-term care (LTC). Without such evidence, people simply see decline and view this area as not worth investing in.

Figure 15-1

Theoretical model of observed versus expected clinical course. The area between the observed and expected outcomes represents the benefits of good care. Thus, a patient’s condition may deteriorate and still be considered as an indication of good care if the rate of deterioration is less than expected.

The alternative model, usually associated with social services, is compensatory care. Under this concept, a person is assessed to determine deficits, and a plan of care is developed to address the identified deficits. Good care is defined as providing services that meet the profile of dependencies and thereby allow the client to enjoy as normal a lifestyle as possible without incurring any adverse consequences.

These two approaches seem at odds, but they could be compatible. Although there is some risk of encouraging dependency with excessive support, providing needed services should enhance functioning or at least slow its decline. Care for the frail older patient requires a synthesis of medical and social attention. One thing is certain. If the medical and social systems are to work together harmoniously, they must share a common set of goals. The first step in collaboration is to identify the common ground to assure both elements are working in the same direction.

The medical care system has not facilitated that interaction. Managed care could provide a framework for achieving this coordination, but the track record so far does not suggest that the incentives are yet in place to produce this effect. A few notable programs have been able to merge funding and services for this frail population. Probably the best example of creative integration is seen in the Program of All-Inclusive Care of the Elderly (PACE), which uses pooled capitated funding from Medicare and Medicaid to provide integrated health and social services to older persons who are deemed to be eligible for nursing home care but who are still living in the community (Kane et al., 2006; Wieland, 2006). The PACE programs have increased, but they are limited because they target a very specific group (persons receiving both Medicare and Medicaid who are eligible for nursing home care but live in the community) and they are expensive. Whether managed care will achieve its potential as a vehicle for improving coordination of care for older persons remains to be seen. In any event, care for older persons will require such integration, and eventually some reconciliation must be achieved about what constitutes the desired goals of such care.

Geriatric care thus implies team care. This concept implies trust in other disciplines with special skills and training to undertake the tasks for which they have the requisite skills. However, these colleagues must not be expected to operate alone. Good communication and coordination will avoid duplication of effort and lead to a better overall outcome. To play a useful role on the health-care team, physicians need to appreciate what other health professions can do and know how and when to call on their skills. Efficient team care does not involve extensive meetings. Rather, information can be communicated by various means. However, good team care will not arise spontaneously. Just as sports teams spend long hours practicing to work collectively, so too must health-care teams develop a knowledge and trust of each other’s inputs. They need a common language and common playbook. Effective teamwork thus requires an investment of effort. Thus, careful thought must be given to when such an investment is justified.

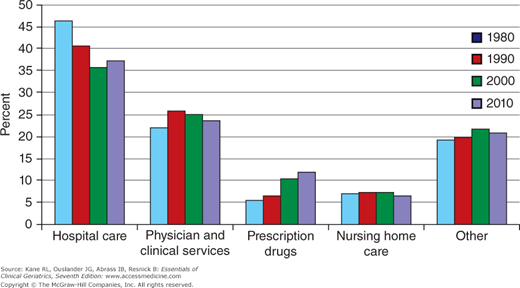

The nature of health care has changed over the past several decades. Figure 15-2 contrasts the patterns of health-care expenditures between 1980 and 2010. There has been a proportionately sharp decrease in the use of hospitals and a marked increase in expenditures on drugs. The costs of physician care (now expanded to include care from nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants) have risen slightly, and the use of nursing homes has declined a little. It is important to recall, however, that spending on health care has increased dramatically from only about $217.2 billion in 1980 to $2,186 trillion in 2010, an increase of about ninefold compared to an increase due to inflation of about 2.65.

Figure 15-2

Distribution of personal health-care expenditure, by type of service: selected calendar years 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010. Other includes other professional services; dental services; other health, residential, and personal care home health care; durable medical equipment; and other nondurable medical equipment. (Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/2011.html. Accessed April 2012.)

Public Programs

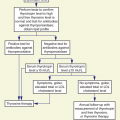

Clinicians caring for elderly patients must have at least a working acquaintance with the major programs that support older people. We are accustomed to thinking about care of older people in association with Medicare. In fact, at least three parts (called Titles) of the Social Security Act provide important benefits for the elderly: Title XVIII (Medicare), Title XIX (Medicaid), and Social Services Block Grants (formerly Title XX). Medicare was designed to address health care, particularly acute-care hospital services. The Medicare program is in flux. Changes in the payment system have been introduced to counter what some saw as abuses (certainly expansions) of the previous system. Medicare was intended to deal with LTC only to the extent that LTC can supplant more expensive hospital care, leaving the major funding for LTC to Medicaid. However, the funding demarcation between acute-care and LTC services became blurred. The imposition of a prospective payment for hospitals created a new market for what became PAC, care that was formerly provided in hospitals but could now be delivered and billed separately by nursing homes, rehabilitation units, or home health care. (The role of Medicare-covered home health care has been made vaguer by a recent court case that seems to broaden its coverage mandate to include at least some chronic care.) The prospective payment approach has been applied to PAC as well. Payment for each type of PAC is based on a separate calculation. Thus, three silos were created, with different approaches to providing similar services. New programs that bundle the payments for PAC and even combine hospital and PAC payments are being proposed and tested.

The distinction in programmatic responsibility between Medicare and Medicaid is a very important one. Whereas Medicare is an insurance-type program to which persons are entitled after contributing a certain amount, Medicaid is a welfare program, eligibility for which depends on a combination of need and poverty. Thus, to become eligible for Medicaid, a person must not only prove illness but also exhaust their personal resources—hardly a situation conducive to restoring autonomy.

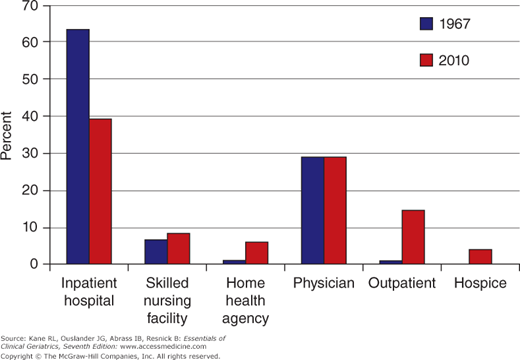

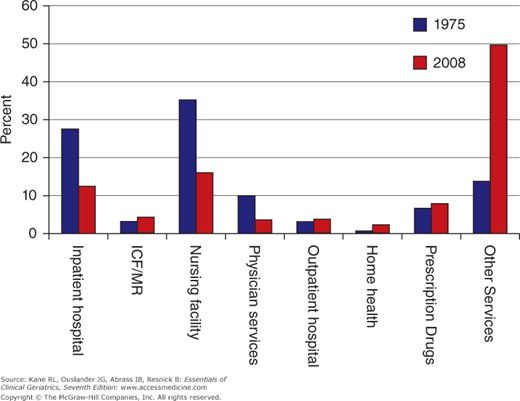

The pattern of coverage is quite different for the various services covered. Figures 15-3 and 15-4 trace spending on health care for elderly persons by Medicare and Medicaid, respectively. Medicare is a major payer of hospital and physician care but pays for only a small portion of nursing home care, whereas just the reverse applies to Medicaid. (Medicare has played a larger role in nursing home and home health care as the role of PAC grew, but new funding priorities have attempted to reduce that role.) Medicare also has a Part D that covers medications; all dually eligible (Medicare and Medicare) beneficiaries receive their mediations through Part D. For Medicare-only beneficiaries, Part D is elective.

Figure 15-3

Percent distribution of Medicare program payments, by type of service: calendar years 1967 and 2010. Note: The Medicare hospice benefit was authorized (effective November 1983) under the Tax Equity Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982. (Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of Information Services. Data from the Medicare Decision Support Access Facility. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/2011.html. Accessed April 2012.)

Figure 15-4

Distribution of Medicaid vendor payments, by type of service: fiscal years 1975 and 2008. Percentages may not add to 100 because of rounding. Other service in 2008 included 22.9% for prepaid health insurance premiums. ICF/MR, intermediate-care facility/mentally retarded. (Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid and State Operations. Statistical report on medical care: eligible, recipient, payments, and services (HCFA 2082) and the Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS). https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/2010.html. Accessed April 2012.)

Eligibility for Medicare differs for each of its two major parts. Part A (Hospital Services Insurance) is available to all who are eligible for Social Security, usually by virtue of paying the Social Security tax for a sufficient number of quarters. This program is supported by a special payroll tax, which goes into the Medicare Trust Fund. Part B (Medical Services Insurance) is offered for a monthly premium, paid by the individual but heavily subsidized by the government (which pays approximately 70% of the cost from general tax revenues). Almost everyone older than age 65 is automatically covered by Part A. One exception is older immigrants, who may not have worked long enough to generate Social Security coverage.

The introduction of prospective payment for hospitals under Medicare created a new set of complications. Hospitals are paid a fixed amount per admission according to the diagnosis-related group (DRG), to which the patient is assigned on the basis of the admitting diagnosis. The rates for DRGs are, in turn, based on expected lengths of stay and intensity of care for each condition. The incentives under such an approach run almost directly contrary to most of the goals of geriatrics. Whereas geriatrics addresses the functional result of multiple interacting problems, DRGs encourage concentration on a single problem. Extra time required to make an appropriate discharge plan is discouraged. Use of ancillary personnel, such as social workers, is similarly discouraged. As a result of DRGs, hospital lengths of stay have decreased, leading to the phenomenon of “quicker and sicker” discharges. Many of these former hospital patients are now cared for through home health and nursing homes. In effect, Medicare is paying for care twice: It pays for the hospital stay regardless of length and then pays for the posthospital care. The rapid rise in this latter sector has led Medicare to search for solutions. Different types of Medicare prospective payment for the different types of posthospital care have been established. Nursing homes are paid on a per-diem basis, whereas home health agencies and rehabilitation units are paid on a per-episode basis. A more effective solution would be to combine the payment for hospital and posthospital care into a single bundled payment, although some fear that such a step would place too much control in the hands of hospitals. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) included a small step in this direction. For selected DRGs, hospital discharges to PAC are treated as transfers. Hospitals receive a lower payment than the usual DRG payment if the length of stay is less than the median.

Up until recently, the payment system was even more paradoxical. The DRG payment was higher for patients with complications, even if those complications arose from treatment during the hospitalization. That approach has been modified to exclude iatrogenic complications, creating a better business case for involving geriatricians in the care of frail patients. Hospitals must now report complications present on admission to avoid having them declared unreimbursible because they arose as part of the hospital care. Likewise, Medicare will not pay for some readmissions within 30 days for the same DRG and imposes a penalty for excessive readmission rates.

The payment systems now in effect create much confusion for Medicare beneficiaries. Although hospitals are paid a fixed amount per case, the patients continue to pay under a system of deductibles and copayments. The majority of Medicare beneficiaries have purchased some form of Medigap insurance to cover these costs, but many variations exist. The picture is even more confused when the Medigap insurance also covers Part D deductibles and copays.

Managed care is aggressively being pursued as an option to traditional fee-for-service care. Under that arrangement, the managed care organizations receive a fixed monthly payment from Medicare in exchange for providing at least the range of services covered by Medicare. In some areas the managed care plans also charge recipients for an additional premium depending on the regional rates. Although many managed care companies were initially attracted to this business because of the generous rates offered, subsequent reductions have made the business less attractive, and many are exiting the program, leaving beneficiaries to scramble for alternative coverage, especially for Medigap policies.

The pricing system used by Medicare to calculate managed care rates basically reflects the prices paid for fee-for-service care in each county. Managed care organizations are paid a fixed amount calculated on the basis of the average amount Medicare paid for its beneficiaries in that county. This adjusted average per capita cost (AAPCC) varies widely from one location to another. Newer approaches to calculating Medicare-managed care premiums use prior utilization and other factors in what is called hierarchical clinical conditions (HCCs). The BBA called for a shift to national pricing. In an effort to attract more providers into managed care, the BBA broadened the definition of what kinds of organizations can provide managed care to Medicare beneficiaries, removing many of the restrictions (especially financial surety bonding) that left managed care largely in the hands of insurance companies. Unlike managed care enrollees in the rest of the population, who are locked into health plans for a year, Medicare beneficiaries have the right to disenroll at any time. Some evidence suggests that Medicare beneficiaries may move in and out of managed care as they use up available benefits. Managed care has become more popular among Medicare beneficiaries, partly fueled by the introduction of Part D. In 2011, Medicare Advantage (the name for managed care under Medicare, often termed Part C) covered 25% of Medicare beneficiaries.

The likelihood of managed care achieving its potential symbiosis with geriatrics appears dim. Ideally, managed care could provide an environment where many of the principles of geriatrics could be implemented to the benefit of all; on the other hand, the performance to date suggests that managed care for Medicare beneficiaries has so far responded more to the incentives from favorable selection (recruiting healthy patients and getting paid average rates), discounted purchasing of services, and barriers to access than to the potential benefits from increased efficiency derived from a geriatric philosophy (Kane, 1998).

The newer approaches use what might be thought of as point-of-service capitation, where payments for service packages are grouped rather than a single payment for all services. Such an approach may make the role of geriatric care more obvious, but this remains to be seen. More likely, investments will focus on using ancillary personnel to coordinate care. For example, medical (or health care) homes may use case coordinators.

Although Medicare does pay for authorized posthospital services in nursing homes and through home health care, the payment for physicians does not encourage their active participation. For example, while a physician would be paid a regular consultation visit fee for daily rounds on a Medicare patient in a hospital, if the patient is discharged to a nursing home the following day, both the rate of physician reimbursement for a visit and the number of visits per week considered customary decrease dramatically. Although physician home visits are still a rarity, payment for these services has increased substantially in recent years. There are now physician groups that have made a business out of nursing home care and home health care. Increasingly the care of nursing home residents falls to nurse practitioners working as part of geriatric care teams. These teams can play two roles in avoiding hospitalizations: (1) They can provide more effective primary care that prevents an episode that would require a hospital transfer. (2) They can manage events that do arise in the nursing home, thus alleviating the need for a transfer.

Medicare coverage is important but not sufficient for three basic reasons: (1) To control use, it mandates deductible and copayment charges for both Parts A and B. (2) It sets physicians’ fees using a complicated formula called the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS). The RBRVS is designed to pay physicians more closely according to the value of their services as determined both within a specialty and across specialties. Theoretically, both the value of the services provided and the investment in training are considered in setting the rates. This new payment approach was intended to increase the payment for primary care relative to surgical specialties, but early reports suggest that, ironically, many geriatric assessment services have been reimbursed at a level lower than before its introduction. Under Medicare Part B, physicians are generally paid less than they would usually bill for the service. (Some physicians opt to bill the patient directly for the difference, but a number of states have mandated that physicians accept “assignment” of Medicare fees, that is, they accept the fee [plus the 20% copayment] as payment in full.) (3) The program does not cover several services essential to patient functioning, such as eyeglasses, hearing aids, and many preventive services (although the benefits for the latter are expanding). Medicare specifically excludes services designed to provide “custodial care”—the very services often most critical to LTC. (However, as noted earlier, the boundary between acute-care and LTC exclusions seems to be eroding.) Work is currently under way to change the way physician fee increases are determined. Basically some combination of cost and quality will be used. In lieu of across the board increases, payments will be based on physician performance.

A major expansion of the Medicare program occurred in 2005 with the passage of the Medicare Modernization Act, which included Part D coverage of drugs. This legislation also provides substantial incentives to Medicare Advantage providers and creates a new class of managed care coverage, Special Needs Plans. These are groups of beneficiaries presumed to be at high risk and hence eligible for higher premiums.

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was primarily aimed at improving access to care for those currently uninsured. Its direct impact on Medicare is modest.

Under Part D, the coverage of prescription drugs involves a complicated formula, often referred to as the “doughnut hole,” because of the odd design of benefits. Basically, the patient pays a deductible ($320 in 2012, but the PPACA reduced the payment). Then the patient pays a copayment (usually around 25%) on yearly drug costs from $320 to $2,930, and the plan pays the majority of these costs. Then the patient pays 100% of the next $1,770 in drug costs (unless she has bought additional drug insurance), and after that, the patients pays a coinsurance amount (eg, 5% of the drug cost) or a copayment (eg, $2.25 or $5.60 for each prescription) for the rest of the calendar year after the patient has spent $4,700 out of pocket. The patient’s plan pays the rest. Part D is administered by a series of drug management firms that offer a confusing array of plans, from a basic plan that covers the Part D pattern to more inclusive coverage that eliminates the doughnut hole. Of course, the premium cost rises as the coverage expands. Plans are required to cover at least two drugs in each identified category, but the choice of drugs is left to them. Medicare beneficiaries must scramble to find the most affordable plan that covers the drugs they need, but even then there is no guarantee that those drugs will continue to be covered.

As a result of these three factors, a substantial amount of the medical bill is left to the individual. Today, elderly persons’ out-of-pocket costs for health care represent about 12.5% of their income. In general, out-of-pocket costs are less for those in managed care.

Medicaid, in contrast to Medicare, is a welfare program designed to serve the poor. It is a state-run program to which the federal government contributes (50%-78% of the costs, depending on the state’s capita income). In some states, persons can be covered as medically indigent even if their income is above the poverty level if their medical expenses would impoverish them. As a welfare program, Medicaid has no deductibles or coinsurance (although current proposals call for modest charges to discourage excess use). It is, however, a welfare program cast in the medical model.

Medicaid is essentially two separate programs, serving two distinct populations. Mothers and young children are covered under Aid to Families with Dependent Children, whereas elderly persons are eligible if they receive Old Age Assistance. The other major route to eligibility for older people is the medically needy program, whereby eligibility is conferred when medical costs—usually nursing homes—exceed a fixed fraction of a person’s income.

Mothers and children use less care per recipient. They use some hospital care around birth and for the small group of severely ill children. A large portion of the Medicaid dollar goes to the services needed by the elderly enrollees, most of whom are also eligible for Medicare, but the services needed are not covered by Medicare; namely, nursing home care and community-based LTC. (Most states automatically enroll eligible Medicaid recipients in Medicare Part B.)

It is important to appreciate that the shape of the Medicaid expenditures for older people is determined largely by the gaps in Medicare. Medicaid has been described as a universal health program that has a deductible of all of your assets and a copay of all of your income. Medicaid is the major source of nursing home payments. It requires physicians to certify a patient’s physical limitations in order to gain the patient admittance to a nursing home. In some cases, physicians are put in a position of inventing medical justifications for primarily social reasons (ie, lack of social supports necessary to remain in the community).

Because it pays about half of the nursing costs but covers almost 70% of the residents, Medicaid shapes nursing home policies. The payment discrepancy is explained by the policies that require residents to expend their own resources first. Thus, Social Security payments, private pensions, and the like are used as primary sources of payment, and Medicaid picks up the remainder. However, it does not directly pay for most physician care in the nursing home; that is covered by Medicare. Medicaid would pay the deductibles and copayments and those services not covered under Medicare. The separation in payment raises policy issues. More aggressive care in nursing homes (paid by Medicaid) can prevent emergency department visits and hospital admissions (paid by Medicare). The nursing homes (and Medicaid) thus underwrite (or cross-subsidize) Medicare savings.

Medicaid also supports home- and community-based LTC services (HCBS). In some states, personal care is included as mandatory Medicaid service under the state’s basic Medicaid coverage plan, but in many states, HCBS is offered as a waivered service. Under this arrangement, the federal government allows states to use money that would otherwise have gone to nursing homes to fund HCBS. The waiver allows states to offer the service in only specific areas and to limit the numbers of persons enrolled in the program. In theory, these funds are supposed to be offset by concomitant savings in nursing home care. The use of HCBS has greatly expanded over the last few decades. Once viewed as simply a cheaper alternative to nursing home care, HCBS is now viewed as the preferred LTC option in many situations (Kane and Kane, 2012).

Whereas going on Medicaid was once seen as a great social embarrassment, associated with accepting public charity, there appears to be a growing sense among many older persons that they are entitled to receive Medicaid help when their health-care expenses, especially their LTC costs, are high. The stigma appears to be displaced by the idea that they paid taxes for many years and are now entitled to reap the rewards. As a result of this shift in sentiment, at least in the states with generous levels of Medicaid eligibility, a burgeoning industry of financial advisers has arisen to assist older persons in preparing to become Medicaid eligible. Because eligibility is usually based on both income and assets, such a step necessitates advance planning. Usually state laws require that assets transferred within 2 or more years (the period varies by state) of applying for Medicaid funds are considered to still be owned. (The situation is more complicated in the case of a married couple, where provisions have been made to allow the spouse to retain part of the family’s assets.) This requirement means that older persons contemplating becoming eligible for Medicaid must be willing to divest themselves of their assets at least several years in advance of the time they expect to need such help. This step places them in a very dependent position, financially and psychologically. Much has been made of the “divestiture phenomenon” whereby older people scheme to divest themselves of their assets in order to qualify for Medicaid, but there is no good evidence about the scale of the phenomenon.

The anticipated LTC Medicaid payment crisis resulting from the demographic shifts has prompted enthusiasm for promoting various forms of private LTC insurance. This coverage, in effect, protects the assets of those who might otherwise be marginally eligible for Medicaid or who simply want to preserve an inheritance for their heirs. Like any insurance linked to age-related events but to a greater degree, LTC insurance is quite affordable when purchased at a young age (when the likelihood of needing it is very low) but becomes quite expensive as the buyer reaches age 75 or older. Thus, those most likely to consider buying it late in life would have to pay a premium close to the average cost of LTC itself and may have prior conditions that render them ineligible. Only a small number of young persons have shown any interest in purchasing such coverage, especially when companies are not anxious to add it to their employee benefit packages as a free benefit. Although economic projections suggest that private LTC insurance is not likely to save substantial money for the Medicaid program, several states have developed programs to encourage individuals to purchase the insurance by offering linked Medicaid benefits.

The decision to purchase LTC insurance needs to be made thoughtfully and carefully. People need to understand the actuarial risks and the financial implications. Purchasing this coverage early means investing money in something you will not likely use for some time with the understanding that this money is not recoverable (because it is term insurance). At the least, potential buyers should be encouraged to purchase plans with cash benefits that are not tied to specific services, because the nature of LTC is likely to change considerably.

A specific group of older people of great policy interest are the so-called “dual-eligibles” or “duals,” who are jointly covered by both Medicare and Medicaid. Not surprisingly, they use more care than those in one program alone. They tend to have more problems. They fall into subgroups. Those receiving LTC use more Medicaid funds, whereas those with multiple comorbidities use more Medicare resources. Given the need for better program coordination and concerns about cross-subsidization, states have shown growing interest in using managed care to take on the care of these groups. Federal programs have been initiated specifically to address care for the dual population. Many of these programs appear to involve active use of managed care.

The third part of the Social Security legislation pertinent to older persons is Title XX, now administered as Social Services Block Grants. This is also a welfare program targeted especially to those on categorical welfare programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children and, more germane, Supplemental Security Income. The latter is a federal program that, as the name implies, supplements Social Security benefits to provide a minimum income. Title XX funds are administered through state and local agencies, which have a substantial amount of flexibility in how they allocate the available money across a variety of stipulated services. The state also has the option of broadening the eligibility criteria to include those just above the poverty line.

Another relevant federal program is Title III of the Older Americans Act. This program is available to all persons over the age of 60 regardless of income. The single largest component goes to support nutrition through congregate meal programs where elderly persons can get a subsidized hot meal, but it also provides meals-on-wheels (home-delivered meals) and a wide variety of other services. Some services duplicate or supplement those covered under Social Security programs; others are unique. Recently, the former Administration on Aging (AoA) supported a number of preventive care initiatives and the Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRC), which provide a point of entry into LTC in most states. In 2012, the AoA was reorganized to merge responsibility for all persons with disability. The new organization, the Administration for Community Living, will bring together the AoA, the Office on Disability, and the Administration on Developmental Disabilities into a single agency that supports both cross-cutting initiatives and efforts focused on the unique needs of individual groups, such as children with developmental disabilities or seniors with dementia. This new agency will work on increasing access to community supports and achieving full community participation for people with disabilities and seniors.

Table 15–1 summarizes these four programs and their current scope. It is important to appreciate that this summary attempts to condense and simplify a complex and ever-changing set of rules and regulations. Physicians should be familiar with the broad scope and limitations of these programs but will have to rely on others, especially social workers, who are familiar with the operating details.

Program | Eligible population | Services covered | Deductibles and copayments |

|---|---|---|---|

Medicare (Title XVIII of the Social Security Act) Part A: Hospital Services Insurance | All persons eligible for social security and others with chronic disabilities, such as end-stage renal disease, plus voluntary enrollees age 65+ years | Per benefit period, “reasonable cost” (DRG-based) for 90 days of hospital care plus 60 lifetime reserve days; 100 days of skilled nursing facility (SNF); home health visits (see text); hospice care* | Full coverage for hospital care after a deductible of about 1 day for days 2-60; then copay for days 61-90. Can use 60 “lifetime reserve” days thereafter. 20 SNF days (after 3-day hospital stay) fully covered; copay for days 21-100; up to 100 days of home health care for homebound persons (after 3-day hospital stay) |

Part B: Supplemental Medical Insurance | All those covered under Part A who elect coverage; participants pay a monthly premium | 80% of “reasonable cost” for physicians’ services; supplies and services related to physician services; outpatient occupational, physical, and speech therapy; diagnostic tests and radiographs; mammograms; surgical dressings; prosthetics; ambulance; durable medical equipment; home health care not covered under Part A | Deductible and 20% copayment (no copay after a limit reached) |

Part C: Medicare Advantage (MA) | Beneficiaries can opt to enroll in a certified managed care program; enrollment is voluntary | MA plans must cover at least all Part A and Part B services. They can reduce copayments and may offer additional services. They also provide Part D coverage. | Plans can charge a monthly premium in addition to the Part B premium |

Part D | Beneficiaries can opt to participate in a standard prescription drug plan. A variety of plans are available through drug benefit companies. Medicaid beneficiaries must be enrolled. Monthly premium varies with coverage arrangement. | Drugs covered in each of a series of mandatory classes but specific drugs vary with each plan. | Annual deductible. Then cost-sharing until the “doughnut hole.” Then plan pays 95% of costs above that |

Medicaid (Title XIX of the Social Security Act) | Persons receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) (such as welfare) or receiving SSI and state supplement or meeting lower eligibility standards used for medical assistance criteria in 1972 or eligible for SSI or were in institutions and eligible for Medicaid in 1973; medically needy, who do not qualify for SSI but have high medical expenses are eligible for Medicaid in some states; eligibility criteria vary from state to state | Mandatory services for categorically needy: inpatient hospital services; outpatient services; SNF; limited home health care; laboratory tests and radiographs; family planning; early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment for children through age 20 Optional services vary from state to state Dental care; therapies; drugs; intermediate-care facilities; extended home health care; private duty nurse; eyeglasses; prostheses; personal-care services; medical transportation and home health-care services (states can limit the amount and duration of services) Some states use extended home care as part of their state plans. Many home- and community-based services are provided under special waivers that allow limited enrollment. | None, once patient spends down to eligibility level Spend-down based on income and assets |

Social Services Block Grant (Title XX of the Social Security Act) | All recipients of TANF and SSI; optionally, those earning up to 115% of state median income and residents of specific geographic areas | Day care; substitute care; protective services; counseling; home-based services; employment, education, and training; health-related services; information and referral; transportation; day services; family planning; legal services; home-delivered and congregate meals | Fees are charged to those with family incomes >80% of state’s median income |

Title III of the Older Americans Act | All persons age 60 and older; low-income, minority, and isolated older persons are special targets | Homemaker; home-delivered meals; home health aides; transportation; legal services; counseling; information and referral plus 19 others (50% of funds must go to those listed) | Some payment may be requested |

Long-Term Care

A proportion of older patients require substantial LTC. There is no uniform definition for LTC, but LTC can be thought of as range of services that addresses the health, personal care, and social needs of individuals who lack some capacity for self-care. Services may be continuous or intermittent but are delivered for sustained periods to individuals who have a demonstrated need, usually measured by some index of functional incapacity. This statement emphasizes the common thread of most discussions of LTC: the dependence of an individual on the services of another for a substantial period. The definition is carefully vague about who provides those services or what they are. Figure 15-5 illustrates the diverse sources of care for frail older people and traces changes between 1999 and 2004. Over two-thirds live in the community. Of these, the majority relies solely on unpaid care, and another large group uses a mixture of paid and unpaid care. A little more than 20% are in nursing homes, and another 8% are in some other form of residential care. As noted earlier, the pattern of LTC has changed substantially over the last decades. HCBS is now a major venue for older persons as well as younger persons with disabilities.