html xmlns=”http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml” xmlns:mml=”http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML” xmlns:epub=”http://www.idpf.org/2007/ops”>

Précis

Definition of terms

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL): for patients suffering from a chronic life condition such as a primary brain malignancy, quality of life (QoL) as defined by one’s health status or HRQoL. HRQoL represents a multidimensional entity that involves physical, emotional, functional, and social aspects of a patient’s life in reference to that patient’s health status and related therapies. In terms of clinical trials, HRQoL is now becoming a frequently used and required outcome and has gained importance in malignancies, such as glioma.

A commonly quoted explanation of general QoL comes from the University of Toronto Research Unit on QoL.1 They define QoL in terms of how the individual functions as himself or herself, within his or her environment, and for the future. The self domain is defined as the “being” and involves physical, psychological, and spiritual realms of self and its existence. The environmental domain is defined as “belonging,” and focuses on how the individual interacts with his or her environment and how these interactions modify and support the physical, psychological, and spiritual components. The “becoming” domain focuses on future goals and how the individual’s current physical, psychological, and spiritual state impacts on attainment of these future goals. HRQoL comes into focus when one looks at the general QoL but now with the subjective experiences and challenges that one experiences during illness, in particular chronic illnesses such as cancer.

Key points to be covered

HRQoL is often impaired during the disease course of glioma patients.

Common symptoms associated with HRQoL in gliomas include fatigue, impaired cognition, and other forms of neurological dysfunction.

Measurement of HRQoL is obtained using standardized validated questionnaires.

HRQoL is becoming a critical component of clinical trial outcomes from glioma and other forms of cancer.

Interventions, whether pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic, are being studied in the glioma population in order to improve HRQoL during the disease course.

Introduction

Historical context

The primary central nervous system tumors account for 1.0% of tumors in the general population and glial tumors, such as high-grade glioma, are the most common type encountered. Despite treatment advances, these tumors, in particular high-grade gliomas, recur within approximately the first 5 months during the initial course of treatment.2 With this commonly expected course, evaluation and maintenance of HRQoL during the disease trajectory have become increasingly important. Moreover, maintenance and improvement of HRQoL are now becoming essential outcome measures in clinical trials. Before and during treatment for high-grade gliomas, adult patients experience a decline in perceived health-related quality of life (HRQoL).3 Liu et al. define quality of life (QoL) as “a concept that encompasses the multidimensional well-being of a person and reflects an individual’s overall satisfaction with life.”3 For brain tumor patients, focal neurological dysfunction, whether cognitive or physical, fatigue associated with treatment, symptoms such as nausea and anorexia associated with treatment, and other common symptoms such as insomnia, seizures, and headaches all have negative impacts on QoL.

Consideration about HRQoL issues in not only the glioma population but also in the general cancer population started to gain recognition in the 1990s. With more clinical trials for cancer occurring and newer chemotherapy agents being utilized, there was a trend to consider not just the symptoms and adverse events that patients experienced but also the impact of HRQoL. Before the 1990s, tools to evaluate HRQoL varied from trial to trial and were not standardized. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) recognized this issue and led an incentive to standardize HRQoL assessments in the setting of clinical trials.4 Similarly, colleagues in the USA developed a standardized validated instrument known as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G).5 With improved ways of measuring HRQoL, advocacy groups such as American Cancer Society, Cancer Quality Alliance, and Susan G. Komen for the Cure have continued to promote HRQoL and survivorship issues. Specifically for primary brain tumors, American Brain Tumor Association and National Brain Tumor Society are two notable advocacy groups that promote HRQoL research for this population.

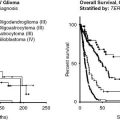

In comparison to age-matched controls, glioma patients experience impairment in HRQoL.6 This phenomenon is not unique to primary brain tumors and is frequently seen and examined in both patients with cancers and patients with other neurological illnesses such as multiple sclerosis. Factors associated with a reduction in HRQoL include size of tumor and grade, with low-grade glioma patients still experiencing deficits in HRQoL, but to a lesser degree than high-grade glioma patients.7 Glioma survivors continue to exhibit negative outcomes in HRQoL, but these are further challenged and impaired once patients experience disease progression and ultimately transition of end-of-life care and/or hospice.8 In summary, HRQoL is a vital component of the experience of glioma patients and is affected in all parts of the illness trajectory.

Summary

This chapter will discuss the definition of HRQoL and how it is measured using patient-reported outcome (PRO) tools. Additionally, specific areas of concern, including fatigue, neurocognition, and mood disturbance, will be presented and research on interventions will be evaluated.

Clinical practice

Approach to evaluate health-related quality of life in glioma patients

Patients with gliomas are subject to developing a unique set of symptoms and medical complications that require specialized evaluation and treatment. These symptoms and complications are managed usually by multidisciplinary providers in neuro-oncology, neurology, neurosurgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, and other medical specialities. Common symptoms that interfere with impairment of HRQoL include fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and mood disturbance. Fatigue is perhaps the most common and ubiquitous symptom, and a comprehensive approach to diagnose, evaluate, and treat potential causes is included in Table 9.1.

| Etiology | Evaluation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Medication: corticosteroid withdrawal | Full medication evaluation with history and physical examination | Modify corticosteroid taper |

| Medication: antiepileptic medication | Full medication evaluation with history and physical examination | Consider changing to less sedative antiepileptic medication or modifying the dose |

| Medication: chemotherapy | Full medication evaluation with history and physical examination | Consider modifying or reducing chemotherapy dose |

| Anemia | Complete blood count with differential | Transfusion |

| Hormonal changes: low testosterone | Free and total testosterone level | Testosterone replacement |

| Hormonal changes: hypothyroidism | Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroxine, triiodothyronine level | Thyroid hormone replacement |

| Hormonal changes: adrenal insufficiency | Cortisol level (a.m.) | Hydrocortisone |

| Depression | Psychiatric evaluation | Antidepressants and/or psychotherapy |

| Deconditioning | Physical therapy | Physical therapy and/or exercise therapy |

| Dyspnea on exertion | Computed tomography angiogram | If positive for pulmonary embolism, consider interventions such as anticoagulation |

Similarly to other impairments in HRQoL, fatigue also exemplifies the fact that the etiology can be multifactorial and these factors are often intertwined. This further supports the utilization of a multidisciplinary team to evaluate glioma patients with HRQoL impairments. Other services, such as social work, psychiatry, psychology, neuropsychology, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy, can provide invaluable resources for assisting patients and caregivers.

Measuring health-related quality of life in gliomas

HRQoL is a subjective patient-generated measure of the physical, functional, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects of patients’ experience as it pertains to their underlying illness and their treatment of that illness.9,10 In clinical trials, HRQoL can be quantified using PRO questionnaires. While these evaluations are subjective, they are standardized and validated self-assessment instruments. Table 9.2 lists commonly used PRO questionnaires in glioma clinical trials. These questionnaires include FACT-G,5 with its associated disease-specific measure of FACT-Br11 for brain tumors, EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30),12 with its associated disease-specific measure of EORTC QLQ-BN2013 for brain tumors, and MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI),14 with its associated disease-specific measure of MDASI-BT15 for brain tumors. FACT-G (version 4), along with the subscale FACT-Br, is commonly used in clinical trials for glioma. FACT-G has a total of 27 items and contains subscales for physical (seven items), functional (seven items), emotional (six items), and social/family (seven items) well-being. The FACT-Br subscale contains an additional 23 items that focus on brain tumor-specific issues and symptoms. Higher scores on the FACT-G and FACT-Br subscale are associated with a better HRQoL, with all items rated on a five-point scale and values summed for the total questionnaire and subscales. EORTC QLQ-30 contains 30 items within five functioning scales: physical functioning (five items), role functioning (two items), emotional functioning (four items), cognitive functioning (two items), and social functioning (two items); global health scale (two items); and three symptom scales: fatigue (three items), pain (two items), and nausea/vomiting (two items). EORTC QLQ-BN20 contains 20 items specific to brain tumor patient symptoms. Most items on the EORTC questionnaires are scored primarily on a four-point scale with a range from “not at all” to “very much,” but some are scored on a seven-point scale from “very poor” to “excellent.” For each item, separate scales, and total questionnaire, it is translated into a linear score of 0–100. MDASI questionnaire and the MDASI-BT contain 19 items and nine items, respectively, and both focus on severity of symptoms and how these symptoms interfere with daily activities of life. For the MDASI and MDASI-BT, the score is obtained by averaging the sum of the items in a subscale or the total questionnaire.

| Name of PRO questionnaire for health-related quality of life (HRQoL) | Components of PRO questionnaire | Brain tumor-specific component |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) | PRO consists of 27 items covering four domains: physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being | FACT-Br subscale: 23 items covering specific areas of concern for patients with brain tumors11 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)12 | PRO consists of 30 items that involve function, symptomatology, global health, and other specific HRQoL concerns | EORTC QLQ-BN20: PRO consists of 20 items that are specific areas of concern for patients with brain tumors13 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI)14 | PRO consists of 19 items on associated cancer-related symptomatology and how it impacts activities of daily living | MDASI-BT: consists of nine items that are specific areas of concern for patients with brain tumors15 |

When designing glioma clinical trials, it is important to consider the amount of HRQoL data that should be obtained and the environment/situation in which the data are obtained. Length of questionnaires and timing of the questionnaires relative to the clinical visit can impact patients’ ability and desire to complete the forms. Thus there are significant clinical trial design issues and biostatistical factors that must be addressed when there are situations such as incomplete or missing data and selection bias. Since patients with primary brain tumors exhibit neurological dysfunction, it can be difficult to obtain reliable data. Use of informant/proxy questionnaires from family and friends can be useful when HRQoL outcomes cannot be obtained directly from the patient.16 Regardless of the PRO questionnaire used in a specific clinical trial, measurement and evaluation of HRQoL in glioma clinical trials are becoming recommended and required outcomes. HRQoL measures are now also becoming useful in the day-to-day clinical practice of the neuro-oncologist, neurologist, medical oncologist, and radiation oncologist who see glioma patients. Whether responses on these questionnaires in day-to-day clinical practice change or modify future outcomes remains to be evaluated.

Health-related quality of life outcomes in newly diagnosed glioma

HRQoL impairment, defined dysfunction in the patient’s perception of his or her well-being in life and the community and its relation to the patient’s goals, expectations, and standards, is present in the glioma population.8,17,18 In a large prospective study of QoL in brain tumor patients, Budrukkar and colleagues found that QOL as rated by scores from questionnaires was low before any type of treatment was started and factors associated with poorer QoL included patients with poor performance status, illiteracy, and more aggressive nature of tumors.19 These impairments are multifactorial and can include neurological dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, fatigue, mood disturbances, physical limitations, and insomnia. Factors associated with HRQoL in the newly diagnosed glioma population include tumor-related factors such as grade, location, and size, along with specific symptoms such as seizures and cognitive dysfunction.20 In an evaluation of patients with newly diagnosed primary brain tumors, patients with high-grade glioma exhibited a greater degree of HRQoL impairment than patients with low-grade glioma and other types of primary brain tumor such as meningiomas and pituitary adenomas.20 Despite this association with grade, HRQoL is still compromised in low-grade glioma patients at time of diagnosis.21 Other factors associated with a poorer HRQoL in this study were also size of the tumor and location of the tumor (anterior vs. posterior), with patients with large tumors and more anterior tumors reporting a poorer HRQoL.20

Health-related quality of life outcomes in recurrent glioma

During the disease trajectory of both low-grade and high-grade glioma, tumor recurrence and/or progression (and, in the case of low-grade glioma, the possibility of tumor transformation) commonly occur. This is a critical point for glioma patients and it has been shown that, at the time of progression and recurrence, glioma patients develop more impairment of their HRQoL.22 Burden of recurrent disease and specific HRQoL of impairments were described by Osoba and colleagues.23 The most common complaints associated with a reduction in HRQoL in recurrent high-grade glioma included fatigue, uncertainty about the future, motor difficulties, drowsiness, communication difficulties, and headache.

Impact of treatment on health-related quality of life in gliomas

Treatment of both low-grade gliomas and high-grade gliomas involves a multidisciplinary approach including surgical resection, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. While these treatments are critical for diagnosis and care of the glioma patient, it is increasingly being recognized that HRQoL can be compromised by these therapies because patients with gliomas are living longer from improved therapies. Maximal safe surgical resection is generally the recommended first approach for gliomas. In the low-grade glioma population, there has been significant debate about whether biopsy/watchful waiting versus early resection improves survival outcomes, but recent work from Jakola and colleagues of 153 patients with low-grade glioma showed that early resection did not compromise HRQoL in comparison to biopsy with watchful waiting.24 Surgery, in particular gross total resection, in glioblastoma has been shown to improve HRQoL primarily because it can alleviate mass effect and increased intracranial pressure that can lead to neurological dysfunction, seizures, and pain.17,25 Logically, if neurologic deficits develop postoperatively in a glioma patient, HRQoL is compromised and Jakola and colleagues suggest that use of more modern surgical techniques could improve HRQoL outcomes.26

After initiation of therapy such as radiation therapy, patients with low-grade glioma develop more complaints of HRQoL impairment, with common aspects of dysfunction, including insomnia, fatigue, seizures, and cognitive decline7,27–32 From EORTC trial 22844 comparing high-dose (59.4 Gy) radiation with low-dose (45 Gy) radiation in low-grade gliomas, the higher doses of radiation were associated with a poorer HRQoL compared to lower doses of radiation.27 Common complaints after radiation therapy included fatigue, malaise, and insomnia. Radiation has similar effects on the high-grade glioma population. In a randomized study of newly diagnosed glioblastoma receiving conventional radiotherapy versus radiotherapy with postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group [RTOG] 93-05), HRQoL declined after radiotherapy in both groups and the extent of deterioration did not differ between the groups.33 Effects of radiation in the high-grade glioma population have been studied in the elderly. In a study by Keime-Guibert and colleagues, elderly (>70 years of age) glioblastoma patients were randomized to best supportive care versus best supportive care with radiotherapy.34 HRQoL was not shown to decline in the radiotherapy patients in comparison to supportive care alone. Limitations of this study were small patient numbers and restriction to a specific population (e.g., elderly).

Addition of temozolomide to radiation therapy in high-grade glioma is now the universal standard of treatment in this population. In a companion study comparing radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy with temozolomide (EORTC trial 26981-22981-National Cancer Institute of Canada [NCIC] CE3), Taphoorn and colleagues evaluated HRQoL in 573 glioblastoma patients. The primary finding relevant to HRQoL was that the addition of temozolomide to radiation therapy did not significantly change or limit the HRQoL in these patients.6 This was a pivotal observation in HRQoL in glioma patients as it not only showed that temozolomide did not negatively impact HRQoL, but also it represented the largest randomized clinical trial to collect HRQoL outcomes. Furthermore, it highlighted the challenges of HRQoL research in that collection of HRQoL can be cumbersome and may be a casualty to patient and provider non-compliance with PRO questionnaires.35

HRQoL has been measured in recurrent high-grade glioma studies involving other chemotherapeutic regimens, including temozolomide, procarbazine, and combination procarbazine, CCNU (lomustine), and vincristine (PCV) chemotherapy.36–39 Specifically for PCV in combination with radiation and in comparison to radiation, side effects such as fatigue, nausea, and vomiting were attributed to PCV chemotherapy and significantly impacted HRQoL near the time of treatment.38 When evaluated longitudinally and in comparison to radiation only, the addition of PCV did not impact the course of HRQoL in high-grade glioma.38,39

There is significant debate on the use of antiangiogenic agents, such as humanized vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, in high-grade glioma and whether there is an impact on HRQoL. In the Avastin in Glioblastoma (AVAglio) study, 458 patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma were randomized to receive either placebo with concurrent temozolomide and radiation followed by adjuvant temozolomide or bevacizumab with concurrent temozolomide and radiation followed by adjuvant temozolomide and bevacizumab.40 HRQoL was measured using EORTC QLQ-C30 and BN20 and results showed that the glioblastoma patients who received bevacizumab maintained a better HRQoL. One associated observation was also that patients in the bevacizumab arm required less corticosteroids and prolonged use of corticosteroids was associated with a reduction in HRQoL associated with steroid-induced weakness.41 RTOG 0825 also evaluated the use of bevacizumab in combination with chemoradiation and has the same randomization and HRQoL PRO questionnaires as AVAglio.42 Despite these similarities, RTOG 0825 demonstrated that glioblastoma patients who received bevacizumab experienced a greater decline in HRQoL over the disease course.

These conflicting results have questioned how bevacizumab impacts HRQoL in high-grade glioma and more research is needed to evaluate this important issue. Smaller studies in regard to the role of bevacizumab in HRQoL maintenance are adding to this important conversation. In the phase II BRAIN study evaluating recurrent glioblastoma treated with either bevacizumab or bevacizumab and irinotecan, bevacizumab was shown to lead to the reduction of corticosteroids and this was proposed to improve on HRQoL in this population.43 Unfortunately, HRQoL data were not evaluated in the form of PRO questionnaires in this study. Similar observations were made by Ngheimphu and colleagues that bevacizumab did lead to a reduction in corticosteroid use in recurrent glioblastoma patients, but it did not specifically use PROs to evaluate HRQoL.44 In a small retrospective analysis in recurrent glioblastoma, bevacizumab was shown to prolong a patient’s independent living status, but results should be interpreted with caution as this was a small sample of 40 patients and the study was retrospective in design.45 Continued research is needed to explore how targeted therapies such as bevacizumab impact HRQoL in high-grade glioma.

Symptomatology and supportive treatment effects on health-related quality of life in gliomas

During the disease course for patients with low-grade and high-grade glioma, symptoms such as fatigue, mood disturbance, seizures, and cognitive dysfunction can readily present.46–48 These symptoms and their treatment can contribute to a glioma patient’s HRQoL and its impairment. Deterioration of neurological function, as seen in neurological examination, is associated significantly with a reduction in HRQoL in high-grade glioma.49 Overall functionality and QoL are particularly important in brain tumor patients since these patients have more dysfunction in these areas than age-matched controls with non-small lung cancer patients.50 Moreover, QoL is dependent on physical function and neurocognition of the brain tumor patient such that patients with better physical function and better neurocognitive function reported having a higher level of QoL.49 Liu and colleagues discuss how these symptoms and signs are interrelated and should not be studied alone such that cognitive decline/dysfunction was associated with increased fatigue and poorer performance status.3,51

Fatigue experienced by glioma patients is likely multifactorial in origin with factors that are tumor-related and treatment-related.52 The relationship between fatigue and HRQoL has been examined in patients with glioblastoma. After radiation therapy, glioblastoma patients have increased fatigue and this increase in fatigue is associated with measurable deficits in HRQoL.53 Long-term survivors of low-grade glioma continue to have complaints of fatigue and it can continue to impact HRQoL.30 Preventing and/or treating fatigue is a potential avenue to explore in the improvement in HRQoL in glioma patients.

Mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety are common in patients with gliomas.54,55 The stress of a neurologic and oncologic diagnosis can be responsible for mood disturbance, but other factors, such as underlying cancer and concomitant medications such as corticosteroids and antiepileptic medications, can predispose to depression, anxiety, and even manic/psychotic episodes. Past psychiatric history should also be considered when evaluating a glioma patient for a mood disturbance. Both emotional stability and psychological distress were found to be important predictors of HRQoL in primary brain tumor patients, including glioma patients, at the time of surgery.56

Seizures are a common symptom in primary tumors, with 30% of patients having seizures at the time of presentation and 40–70% of patients experiencing a seizure during the disease trajectory.57 The effect of epilepsy and antiepileptics on HRQoL has been extensively explored. Studies have investigated HRQoL in patients with low-grade glioma and presence of epilepsy has been associated with significant impairment in HRQoL.32 Alone, epilepsy can be the culprit for the reduction in HRQoL, but Klein and colleagues also made observations that HRQoL and cognitive function can also be impaired by the treatment of seizures with antiepileptic drugs.32 In a retrospective analysis of primary brain tumor patients with epilepsy, polytherapy with antiepileptics was associated with a reduction in HRQoL.58 Interestingly, factors such as number of seizures and neurological performance were not related to HRQoL. Specific antiepileptics have been studied in the primary brain tumor population and HRQoL has been assessed in concert with seizure control. Both oxcarbazepine and levetiracetam have been studied as monotherapy in primary brain tumor patients and neither had significant deleterious effects on HRQoL.59,60 Pregabalin was studied as an adjunctive agent and HRQoL was found to be improved in specific subscales involving decrease in distress scores related to antiepileptics and social life.61 This suggests that, in the care of gliomas, providers need to monitor HRQoL and balance treatments for comorbid conditions such as epilepsy and cognitive dysfunction carefully.

Neurocognitive dysfunction, whether it develops due to the underlying tumor, treatment, or use of medications such as antiepileptics and corticosteroids, usually comes in concert with a reduction in HRQoL. In both newly diagnosed and recurrent high-grade gliomas, reduction in neurocognitive function was associated with a reduction in reported HRQoL.49,50,62 When compared to healthy controls or patients with other malignancies, high-grade glioma patients experience a great degree of neurocognitive impairment and related reduction in HRQoL.50 Similar observations have been made in the low-grade glioma population.7,21 In comparison to healthy controls and patients with other malignancy, low-grade glioma patients exhibit neurocognitive deficits and associated impairment in HRQoL.7 On the other hand, severe neurocognitive dysfunction can often limit the ability to collect reliable HRQoL measurements because the patient may not be able to report dysfunction. Informant questionnaires from family and friends have the potential to be useful in these scenarios. The means to improve cognition or to develop coping skills to deal with neurocognitive deficits are being explored to improve on cognition and in turn to improve HRQoL.

For practicing neuro-oncologists, medical oncologists, neurologists, radiation oncologists, and neurosurgeons who treat glioma patients, there is regular evaluation of these symptoms (fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and seizures) and their effects on HRQoL. Fatigue evaluation and management often include hormonal testing for adrenal insufficiency, testosterone insufficiency, and thyroid dysfunction and replacement of these hormones if warranted. Referral to physical therapy and occupational therapy can be helpful and is commonly utilized when patients exhibit fatigue and deconditioning that interfere with HRQoL.63 Rehabilitation and physical therapy can be used to improve fatigue symptoms and QoL in primary brain tumor patients.52 Recognition and treatment of comorbid mood disturbance are common and can be beneficial in patients with both low-grade and high-grade glioma. Antidepressants, in particular selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, can be used safely in glioma patients, but comorbid conditions such as testosterone insufficiency or thyroid dysfunction should also be considered in glioma patients with depression.64 Referral to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health care providers is often warranted in patients with gliomas and, in some academic centers, these professionals are integrated into the neuro-oncology practice. Support groups for patients and families can also be beneficial when dealing with mood disturbance and HRQoL.65 In the treatment of seizures and epilepsy in glioma patients, care should be taken to evaluate how the patient responds clinically to the antiepileptics and mitigates side effects, such as cognitive dysfunction and fatigue, that would impact negatively on HRQoL.57

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree