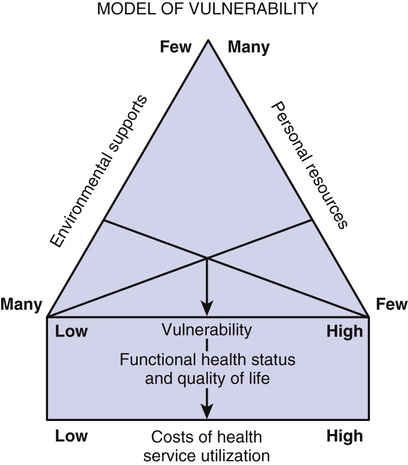

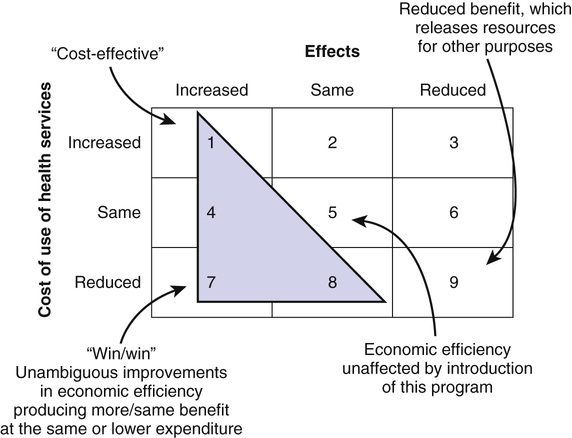

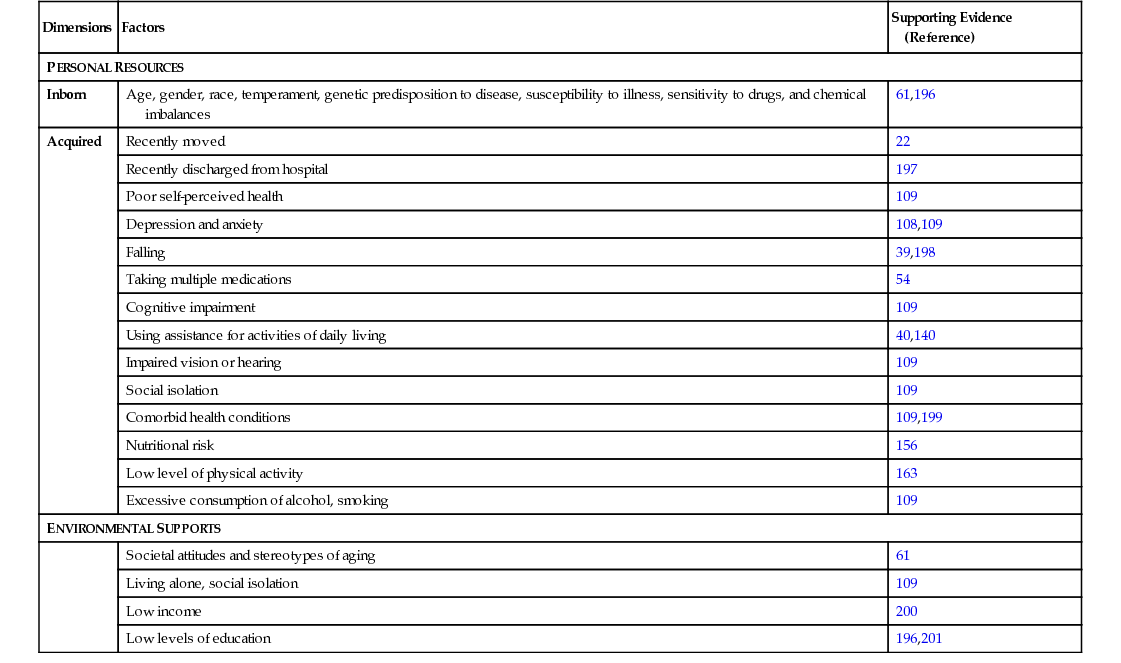

Maureen F. Markle-Reid, Heather H. Keller, Gina Browne The older adult population (older than 65 years) is growing worldwide1 as a result of economic prosperity and improved health care, sanitation, and education. In Canada, as the baby boom generation reaches the age of 65, seniors will make up a substantial part of the population: about 23% of Canadians by 2030 will be old by today’s standards. The fastest-growing segment is people 80 years and older; this reality has implications for how we provide health care.2 Increasingly, as in many countries, Canada’s older citizens are aging in place, a change attributable to technologic advances, investments in affordable and social housing, age-friendly communities, support for caregivers, programs to combat homelessness, and changes in options for care. In 2011 in Canada, 92% of seniors lived in a private home.2 Rates of institutionalization for older people have decreased and formal community-based care has expanded, such that the proportion of older people receiving community care now outweighs that receiving services through an institution.3 Over the past two decades, hospital beds have been reduced by 30%, nursing home beds by 11%, and ambulatory care has increased. The result is increasing pressure on community-based services to maintain accessible, high-quality, and comprehensive health care despite economic constraints.3–5 The benefits associated with aging in place are well documented. Residing at home optimizes older persons’ health,6,7 independence, control, sense of well-being,8 and social connectedness.7,9 Managers and policy makers face questions about the most efficient mix of service strategies for health promotion in this more community-based system. As the population of older adults increases and medical advances continue to convert previously acute life-threatening diseases into chronic illnesses, there is an associated increase in the prevalence of chronic conditions and frailty.10–12 More than 90% of older adults live with at least one chronic disease requiring daily self-care and management13 and 65% to 85% have two or more chronic diseases.14 Approximately 33% of community-living older adults have multiple chronic conditions (three or more).15 Seniors with three or more chronic conditions report poorer health status, take five or more medications, have higher rates of health care utilization, and are at high risk for adverse events (e.g., death, hospitalization, and falls).15,16 They account for 40% of health care use among seniors in Canada, with the intensity of use increasing as the number of chronic conditions increases.15 Left unchecked, these conditions may overwhelm the health care system and threaten its sustainability.17 The long-term solution must involve health promotion to prevent or better manage these conditions to improve quality of life and reduce demand for health care services.18 Approximately 15% of community-living seniors fall into the category of frail, defined as the accumulation of multiple interacting illnesses, impairments, and disabilities.12,19,20 Of those considered frail, 17% are at high risk of experiencing functional decline that will jeopardize their ability to live independently.21 These people are typically 75 years of age or older, living with multiple acute and chronic health conditions and functional disabilities.22 They may also have cognitive impairment or unstable social support networks.22,23 These characteristics put frail older adults at increased risk for morbidity, disability, health service use, and death.24 However, chronic disease and frailty should not be considered an inevitable or irreversible consequence of aging.25 As individuals age, they are at greater risk of developing chronic health problems, but these conditions are not inherent in the aging process.26 A majority of the most costly health conditions are preventable, treatable, or manageable.18 At least one third of the total economic and social burden of disease in developed countries is caused by a handful of largely avoidable risks: tobacco, alcohol, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity.27–29 Evidence suggests that chronic disease is preventable and can be better managed to reduce its health and economic effects on older adults. Many chronic disease risk factors, such as physical inactivity and poor nutrition, are modifiable. The negative effects of many risk factors can be reversed, with even modest reductions in risk factor levels producing large improvements in health.30 For example, with healthy eating, regular exercise, not smoking, and effective stress management, over 90% of cases of type 2 diabetes and 80% of cases of coronary heart disease could be avoided.27,28 Even a 5% reduction in preventable illnesses could lead to substantial savings in medical and other costs.18 Consequently, identifying modifiable factors that can reduce or delay health service use and increase quality of life in older adults is a priority. Family caregivers, particularly women, provide up to 80% of the care for community-living older adults with chronic conditions or disabilities. These caregivers provide vital help with activities of daily living, such as personal hygiene, toileting, eating, and moving about inside the home. Family caregivers also help with meal preparation, housework, medication management, shopping, and transportation and provide emotional support.31 In 2012, an estimated 8.1 million Canadians provided care to a family member or friend with a long-term health condition or aging-related needs.32 Although many caregivers find this to be a rewarding role, it is often carried out at the expense of their own health and well-being. The level of caregiver strain increases with the number of chronic conditions the older adult has, resulting in negative health outcomes and more health service use in caregivers.33 Despite this evidence, little is known about the best way to support family caregivers. A growing body of research suggests that older community-living adults can benefit considerably from proactive health promotion interventions.34–41 The ultimate goal of these programs is to proactively identify and address factors influencing health and to promote positive health behaviors and autonomy of older people living in the community to prevent or delay institutionalization, reduce health care costs, and improve health-related quality of life and function.42 The purpose of this chapter is to summarize this research and identify how health promotion and disease prevention for community-living older adults can be improved. The specific objectives of this chapter are (1) to describe three groups of older adults and their need for health promotion and disease prevention, (2) to describe a conceptual framework for health promotion and disease prevention for frail older adults, (3) to describe a framework for economic evaluation of health care programs, (4) to argue in favor of the importance of screening to identify older adults who could benefit from health promotion and disease prevention efforts, (5) to describe successful health promotion and prevention efforts among community-living older adults, (6) to discuss the barriers to implementing effective health promotion programs, and (7) to demonstrate the need for further policy and research on health promotion and disease prevention for community-living older adults. Older adults are a very heterogeneous group, with aging occurring at different rates in different people. Chronological age does not tell the full story of functional ability or quality of life, and most disabilities of old age are not inevitable.25 The trajectories of aging after age 65 have been described as “successful,” “usual,” and “accelerated.”43–45 Those who are successfully aging continue to experience good health for an extended period of time. “This is the 65-year old who plans to take a cycling tour of France, the 75-year old who plays tennis twice a week, or the 80-year old who walks two miles each day.”43 Successfully aging adults have minimal health problems; they may visit their primary health care provider for preventive checks, such as blood pressure, and may have a few risk factors (e.g., family history of heart disease), but they are quite healthy, with no modifiable risk factors. These older adults are likely to be on no medications. They watch what they eat and try to exercise. They develop signs of chronic disease only late in life, thus spending less time dealing with chronic disease.43 Usually aging older adults have some signs of chronic disease. They take a few medications to manage hypertension or cholesterol levels, may be bothered by the occasional bout of arthritis pain, and see their doctor routinely to monitor their conditions. These conditions do not drastically affect their quality of life, because they still travel and do most of their normal activities, such as driving, babysitting grandchildren, and taking cruises.43 Approximately 80% of seniors are experiencing successful or usual aging.46 Older adults experiencing accelerated aging appear frailer and more functionally dependent for their age. These people, who represent between 15% and 20% of seniors, are typically older than 75 years and have co-occurring physical health problems, both acute and chronic.20,47 They are highly vulnerable, living with supports that are prone to breakdown with any shift in their health and well-being.21–23 Many live in isolation and are cut off from community services because of a lack of information or transportation or the will to initiate action.48 Many single seniors live in poverty or near-poverty, without the benefit of the two pensions that married older adults get.49 The prevalence of depression among those with accelerated aging is between 26% and 44%, at least twice that among older people in general.50 These characteristics lead to a greater risk for loss of functional independence, institutionalization, and death.12 Long-term care facilities take care of approximately 25% of seniors with accelerated aging and the remainder reside at home.20 These frail older adults pose a challenge to health care systems, because they are frequent users of acute hospitalization and home care services.23,38 Frail seniors living at home are particularly difficult to reach and are at high risk for loss of functional independence and institutionalization.12 These facts underline the need for health promotion efforts in this group. Before discussing health promotion and disease prevention in relation to frail older adults, it is important to clarify what is meant by “frailty” (see also Chapter 14). Despite the recent increase in the use of this term, there is a lack of consensus about frailty and its meaning, beyond agreement that people who are frail are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes compared with others their own age.24 What does frailty look like? How is it defined, framed, and understood? Exactly how frail is frail?51,52 A first step in addressing the problem of frailty is to understand better how to identify those who are frail.53 However, the components of frailty have not been sufficiently defined to identify populations at risk or in need of proactive interventions.24 A literature review of definitions and conceptual models of frailty in relation to older adults suggests that frailty is a multiple-determined state of vulnerability in which an individual is at risk of becoming more or less frail over time.24 The implication of this definition is that the process of frailty can be modified or reversed,24 highlighting the need for rational, theoretically based interventions directed toward health promotion and disease prevention for this population. This chapter gives guidelines for a taking a new theoretical approach to the concept of frailty in older adults. This new approach to the concept of frailty (1) is multidimensional and considers the complex interplay among behavioral, biological, social, and environmental determinants of health rather than a single influence12,54,55; (2) is not age-related; (3) is subjectively defined; and (4) considers both individual and environmental factors that influence health (Table 97-1).24 TABLE 97-1 Dimensions of Frailty Despite the differences in the three types of aging groups, each could benefit from health promotion and disease prevention efforts targeted to its specific needs.28,38 Programs and services that promote the health of older adults, focused on keeping them healthy rather than solely being reactive to symptoms, are underdeveloped in North America.45,56 The lack of such programs may reflect the narrow viewpoint that older adults cannot change behaviors such as smoking, eating, and exercising.57 However, seniors are interested and can change behaviors when given the support to do so. Calls have been made for the development of more public health interventions for older adults58 that target motivation to acquire or maintain important health behaviors. The goal of any health promotion program should be to optimize the individual’s current health, even if minimal change in quality of life is achieved.1 Given the heterogeneity of older adults, it is essential to consider differences in health trajectories and quality of life when making decisions about the type and number of health promotion activities required. As the population ages and the number of people aging in place increases, there is an urgent need to identify effective and efficient ways of promoting the health of community-living older adults. Empirical evidence alone is insufficient to direct the design and evaluation of interventions. Theory is essential for program development, implementation, and evaluation, as it provides explanation and can predict outcomes. Theory enhances the generalizability of the results by providing the basis for the systematic development and implementation of intervention strategies, as well as evaluation indicators.59 Furthermore, there is evidence to support higher effectiveness of theory-based versus non–theory-informed interventions.60 An adapted version of the model of vulnerability61 incorporates the key concepts of frailty (discussed earlier) to guide the development, implementation, and evaluation of health promotion and disease prevention interventions. Vulnerability is a net result of the interaction between a person’s personal resources (cognitive, emotional, intellectual, and behavioral) and environmental supports (social, material, and cultural), both of which, along with biologic characteristics (age, gender, and genetic endowment), are determinants of health. Within an individual, personal resources and environmental supports intersect, as shown in Figure 97-1, and can be synergistic and cumulative.39 The base of the triangle represents the degree of vulnerability61 and thus also health status and quality of life. Use of health services increases with the level of vulnerability.34 Even if personal resources hold constant, changes in the individual’s environmental supports can alter his or her degree of vulnerability and thus his or her use of health and social services.39 What is needed is “a ‘fit’ between the needs and resources of the person and the demands and resources of the environment” (p. 68).61 This vulnerability model provides a schema of the basic components of a multidimensional health promotion and disease prevention intervention. Such interventions, targeted at either the individual or the environment, can identify and strengthen available resources, thereby reducing vulnerability and the on-demand use of expensive health services, while enhancing quality of life. Hence, strategies for optimizing health in the model of vulnerability are multilevel.61 Personal resources can be defined as either inborn or acquired characteristics, which interact with the environment to influence health.61 Inborn characteristics include nonmodifiable factors such as age, gender, race, temperament, genetic predisposition to disease, susceptibility to illness, sensitivity to drugs, and chemical imbalances. Acquired characteristics are modifiable factors known to increase risk for functional decline in older adults. Environmental supports are factors that interact with personal resources to influence health61 (Table 97-2). TABLE 97-2 Model of Vulnerability Although the literature contains many evaluations of programs seeking to achieve improved outcomes for vulnerable populations, such as frail older community-dwelling adults, few of them evaluated the efficiency of these programs. In economic terms, efficiency involves maximizing outcomes for a given cost or minimizing costs for a given level of outcome.62 As depicted in Figure 97-2, the economic evaluation of health care programs63 yields nine possible outcomes (the more favorable ones are within the triangle). In outcome 1, increased effects or health benefits are achieved with increased expenditure or additional resources consumed—this is called cost-effective. Outcome 4 is also favorable, because increased effects are achieved at equivalent costs. Outcome 7 represents the “win/win” situation, whereby more effect is produced at lower costs. Outcome 8 represents the situation where different health programs produce the same effect, but some approaches are associated with lower costs. Options 7 and 8 are superior to the often-implemented option 9, in which funding for a program is cut because of reduced effects, releasing resources for other purposes.63 This approach can be used to classify the main effects and expenses of comparative community health interventions. In addition, it can be used to determine who benefits most and at what expense when various interventions are available. This is of concern especially in systems of government health insurance, in which some people may use services inappropriately.64 A growing body of international evidence suggests that early detection of older people at risk for functional decline or loss of autonomy is beneficial. Several studies of screening and case finding have been conducted to proactively identify and address unmet needs of older adults, to reduce the on-demand use of costly resources. These will be reviewed here. Many older adults living the community have unrecognized risk factors. Health concerns or risk occur in almost all older adults, with up to 83% having at least one unreported or unrecognized risk.65–67 Many of these risk factors are social problems67 that can affect a senior’s support network and have the potential to increase health care expenditures if left undetected. Unsolicited home visits by a health visitor can be a means of recognizing these unmet needs. Using this service, Harrison and colleagues68 found that 35% of patients older than 70 years of age had unidentified risks and could benefit from preventive programs. Brown and coworkers,69 in an audit of 40 general practices in the United Kingdom, reported that 44% of patients older than 75 years had at least one health problem that was previously undetected. Ramsdell and associates70 found that compared with an office-based assessment, a home-based assessment of older adults resulted in the detection of up to four new problems. Stuck and colleagues71 identified several key advantages of in-home visits versus office-based visits. A home-based assessment allows for appraisal of the physical environment to identify risk factors and equipment needs, review of medications, contact with family members, and convenience for clients with mobility problems. Furthermore, an office-based visit often has a specific focus and limited time to solicit additional risks. Browne and coworkers,34 in a review of 12 randomized controlled trials evaluating a community-based approach to care in a Canadian setting, found that for clients with multiple problems (such as the frail older adult), it is more expensive to not provide proactive and comprehensive disease prevention and health promotion. Similarly, Caulfield and associates65 (p. 87), in a review of the literature on geriatric screening programs, concluded that “home based, comprehensive screening of the older adult for undetected physical, mental and socioeconomic problems by nursing or other trained personnel may be able to prolong survival, improve quality of life, and perhaps even postpone dependency or institutionalization.” Screening eliminates a barrier between the need for help and gaining access to that help. Screening and assessment in three areas—falls, nutrition, and depression—are advocated for community-dwelling older adults, because these conditions are readily preventable through health promotion efforts. The term screening refers to the process of detecting or identifying a health condition or risk factor among a specific population. The term assessment refers to the process that follows a positive screen and involves evaluating older adults in a more specific way to confirm the problem or establish the diagnosis and develop a treatment plan.72 As detailed in the chapter on mobility and its assessment (see Chapter 102), falls and fall-related injuries negatively affect older adults’ quality of life and health care resources. Thirty percent of community-living adults older than 65 years fall at least once a year, increasing to 50% for those older than 80 years.73 Fall-related injuries often trigger a downward spiral in health that is associated with activity restriction,74 high health care costs,75 long-term care admissions,76 and death.77 The costs of health care associated with fall-related injuries are staggering. The 2004 cost of fall injuries to seniors in Canada was $4.5 billion. With an aging population and an associated increase in fall-related injuries, these cost estimates are projected to rise as high as $240 billion by 2040.75 Aside from the cost, the negative effect of a fall on health and quality of life should not be underestimated. Fall injuries often result in fear of falling,78,79 leading to self-imposed restriction of activity and loss of confidence,80 low self-esteem, depression,79 chronic pain, and functional deterioration.81 Falls and fall-related injuries and complications are the leading cause of death among seniors.82 Frail seniors are at increased risk of falls,83 are more likely to sustain serious injury, and take longer to recover after falling.75 Falls are caused by multiple interacting factors, some of which are modifiable. Factors such as postural hypotension; the use of multiple medications; and impairments in cognition, vision, balance, gait, and strength increase the risk of falling.84 Although no single factor causes all falls, the risk of falling increases with the number of risk factors present.85 Evidence suggests that most falls are predictable and preventable. Intervention studies showed that 30% to 40% of falls can be avoided.86–88 A 10% reduction in the number of nonfatal falls would mean 7931 fewer falls and health care savings of $138.6 million.18 Categorizing individuals into different levels of risk through screening is important from both clinical and economic perspectives; it is the seniors with the highest risk of falling who will benefit most from preventive efforts.87 Preventing falls in any group of older persons requires knowledge of where that group sits on the risk spectrum, because this will determine the type and amount of services required, as well as the effectiveness of the program.81 Fall risk screening is a means of targeting limited home and community care resources. Home and community care providers are well positioned to play a major role in preventing falls in older people through screening and intervention. Because of the rising concern for fall-related injuries, several fall risk screening instruments for community-living older adults have been developed.89 The most effective fall reduction programs involve routine and systematic fall risk assessments, followed by targeting of interventions to an individual’s risk profile.83,90 This conclusion has been substantiated by meta-analyses of many randomized controlled trials90,91 and by consensus panels of experts who have developed evidence-based practice guidelines for the detection and management of fall risk.83,92,93,87 The importance of this direction cannot be overstated. Reducing just one fall risk factor can have a great effect on the frequency and morbidity of falls.88 Nutrition problems in older adults are common, because of the diverse determinants of food intake in this age group44 (see also Chapters 79 and 109). Low intakes of various food groups, energy, protein, and micronutrients in the older adult population have been reported.38,94 Poor-quality, energy-dense food, and lack of exercise lead to obesity.94 Obesity, coupled with poor function, results in a precarious state for older adults. Those who are frail, exhibiting accelerated aging, are also highly susceptible to malnutrition.38,94,95 Several nutrition screening indices have been developed96 in response to concerns for the nutritional health of older adults.38,57 Nutrition screening is a means of targeting limited nutrition resources, especially dietitian services.97 Unfortunately, most research to date has focused on describing “at-risk” populations or identifying linkages between nutrition risk and negative health outcomes, without demonstrating that nutrition screening can change practice and prevent these outcomes. Prevalence of risk varies, depending on the index used and the subgroup of older adults screened; estimates range from 34% in “usually aging” seniors to 69% in those who are frail.98–101 Risk factors associated with poor food intake or nutrition risk include poor self-rated health,100,102 functional limitations,44,102,103 education, income, social support, dentition, smoking, vision,98,102,103 stress,99 lack of transportation, poor social networks, and living alone.38,98 Food intake is very complex because of its multifactorial determinants. Interventions to promote food intake need to be comprehensive and multisectoral. In the United States, the Elderly Nutrition Program provides nutritious meals and other nutrition services to older adults who are especially vulnerable.94 Although not mandatory, screening, assessment, and interventions, such as counseling and basic nutrition education, can be provided within individual communities. Screening within the program is meant to target interventions,94 but no research on the effectiveness of the screening process has been documented. Only 20% of older adults who could benefit from this program are reached,104 and targeting of services to those most in need is required.105 A 2008 article described a nutrition screening program with the Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 in 26 European hospital departments in 12 countries.106 The average age of the 5051 patients screened was 60 years, and 33% were considered to be “at risk.” These patients were more likely to have complications, death, and a longer length of hospital stay than those without risk. Subsequent interventions, if any, were not described. Regardless of setting, screening needs to be followed with assessment and efficacious treatment. There is only one known evaluation of a nutrition screening program focused on older adults in the community, limited to describing and assessing the process of screening.43 The Bringing Nutrition Screening to Seniors in Canada project43 involved developing, implementing, and process evaluating screening programs in five diverse communities in Canada. Approximately 1200 seniors were screened. Those who were found to be at risk were provided with referrals to community services. An ethical screening process, which included follow-up, helped to identify the effect of the program. Seniors indicated that screening helped them recognize their problem areas and become aware of the programs and services available in their community. Some individuals reported improving their food intake as a result of the screening, although objective data were not collected.43 Now that nutrition screening tools are available, researchers need to focus on determining the effectiveness of screening and early nutrition interventions in this population. Depression is one of the most common treatable causes of mortality, morbidity, functional decline, and increased health care use among community-living older adults.107–109 Despite the high prevalence of depression in this population, its incidence is often missed or suboptimally managed.110 Depression affects 5% to 10% of individuals in primary care but is recognized in only about 50% of cases.111 In a recent study of older adults receiving home care services, only 12% of those with depression received adequate treatment.110 Many challenges to the diagnosis and management of depression in older adults have been identified, including difficulties disentangling coexisting medical, psychiatric, and social morbidity112; transportation and access difficulties; social isolation113; health care provider attitudes toward mental health disorders and treatment; and reluctance of older adults to accept the diagnosis of depression.114,115 Thus, seniors may be particularly vulnerable to suboptimal depression care. The magnitude of the problem has potential to increase as a result of the rising number of seniors46 and the associated increase in the prevalence of depressive symptoms.72 Clinician and health care system factors also impede the recognition and treatment of depression. Older people at risk of, suffering from, or recovering from depression have limited access to professional services promoting mental health, especially nursing.116 Other barriers to optimal depression care include inadequate collaboration among home and community care providers, primary health care providers, and specialized mental health care providers; no continuity among providers; difficulties accessing specialized mental health care services; lack of knowledge among home care providers in recognizing and managing depression113,116–118; and underuse of depression screening tools. A final barrier is the lack of evidence-based practice standards specific to the assessment and management of depression in home care for older adults.116 Unrecognized, untreated, and undertreated mood disorders generate enormous personal, economic, and societal costs.110,119 Depression in older people often coexists with other chronic illnesses, and untreated depression is a significant risk factor for functional decline, diminished quality of life, mortality from comorbid medical conditions or suicide, dementia, social isolation, poor adherence to treatment, increased demands on family caregivers, and increased use of expensive health services.120,121 In 1998, depression cost Canadians approximately $14.4 billion dollars.122,123 These costs are compounded by indirect costs, such as those to family caregivers, who are more prone that non-caregivers to experience symptoms of depression.124 Depression is also associated with unhealthy lifestyles and noncompliance with medical treatment.125,126 Frail seniors are at increased risk of depression.19,127 The prevalence of depression among frail older persons receiving home care services is 26% to 44%, at least twice that among older persons in general.110,128,129 They also suffer from a fourfold increase in more severe forms of depression than the general population.130 Clearly, recognition is key to referral and subsequent treatment for depression in this population.115 Multiple interacting physical, psychological, and social factors increase the risk of depression in old age. These include comorbid health condition(s); functional limitations; taking medications such as centrally acting antihypertensive drugs, analgesics, steroids, and antiparkinsonian agents; social factors; and history of depression.131 Routine depression screening and assessment have been shown to improve the recognition and management of depression in community-living older adults.115,117,132–137 Several instruments have been developed to reflect the differences in presentation of depression in older adults and to address such issues as the presence of concurrent medical disorders (e.g., dementia).138 Community providers can play a pivotal role in screening for depression in older adults. An understanding of the risk factors for depression will increase clinicians’ ability to effectively target the use of screening, because screening is most effective when targeted to higher risk groups.72 Current Canadian recommendations suggest that screening for depression in primary care settings should only be carried out if effective follow-up and treatment can be provided.139 Although access to specialized geriatric mental health services remains limited in some settings, primary health care practitioners are able to provide appropriate follow-up and treatment.72

Health Promotion for Community-Living Older Adults

Introduction

The Heterogeneity of Older Adults and the Need for Health Promotion

Dimensions

Supporting Evidence

The concept must be multidimensional and consider the complex interplay among behavioral, biologic, social, and environmental determinants on health rather than a single influence.

This view is consistent with the observation that many social, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors are associated with health and that determinants of health are often highly inter-related.12,54,55 Theoretical models need to address the complexity of problems rather than focusing on a single problem, since older people typically have co-existing physical, emotional, and social problems interrelated with one another and with external factors.24,192

The concept must not suggest a negative and stereotypical view of aging.

Theoretical models should reflect a positive view of aging that emphasizes the capacity for autonomy and independence and maximizes a person’s strengths193 as well as deficits.24

The concept must take into account an individual’s context and incorporate subjective perceptions.

The trajectory of frailty is unique for each individual.194 The emphasis is on the individual’s perception of health rather than the person’s objective circumstances. Research supports the hypothesis that an individual’s poor adjustment to chronic illness or affective state is not related to the specific physical disease or level of disability but rather to the negative meaning the individual attributes to it.195 Theoretical models need to incorporate subjective measures and allow for individual variability.24

The concept must take into account the contribution of both individual and environmental factors that influence health.

Frailty can originate from within an individual or from conditions in the environment. Theoretical models need to address the constellation of individual and environmental factors that influence health.24

Conceptual Framework for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention for Frail Older Adults

Dimensions

Factors

Supporting Evidence (Reference)

PERSONAL RESOURCES

Inborn

Age, gender, race, temperament, genetic predisposition to disease, susceptibility to illness, sensitivity to drugs, and chemical imbalances

61,196

Acquired

Recently moved

22

Recently discharged from hospital

197

Poor self-perceived health

109

Depression and anxiety

108,109

Falling

39,198

Taking multiple medications

54

Cognitive impairment

109

Using assistance for activities of daily living

40,140

Impaired vision or hearing

109

Social isolation

109

Comorbid health conditions

109,199

Nutritional risk

156

Low level of physical activity

163

Excessive consumption of alcohol, smoking

109

ENVIRONMENTAL SUPPORTS

Societal attitudes and stereotypes of aging

61

Living alone, social isolation

109

Low income

200

Low levels of education

196,201

Framework for Economic Evaluation

Screening and Assessment: Identifying Older Adults Who Could Benefit From Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Efforts

Risk of Falls

Risk of Nutritional Problems

Risk of Depression

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health Promotion for Community-Living Older Adults

97