Health of the World’s Adolescents and Young Adults

Dougal S. Hargreaves

Kristin Wunder

Russell M. Viner

John Santelli

KEY WORDS

Demography

Global health

Health disparities

Health status

Morbidity and mortality

Social determinants of health

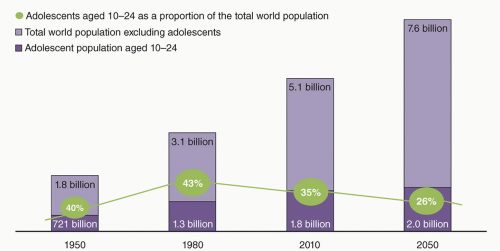

The world now has the largest generation of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) in history: 1.2 billion aged 10 to 19 years (17.3% of the world population) and 1.8 billion aged 10 to 24 years (26.3% of the world population).1 This “youth bulge,” seen particularly in rapidly developing low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), has the potential to deliver a substantial economic and productivity dividend for countries as this better educated generation of youth enter the workforce.2

Adolescence and young adulthood have been considered the healthiest times of life, and therefore have received little attention in terms of global health policy and perspectives. However, recently there has been greater focus on AYA health, highlighting emerging patterns of global mortality, high rates of health-risk behaviors, and morbidity, and recognizing that health patterns among AYAs have lifelong consequences. Recent decades have seen rapid reductions in global mortality among young children, but much smaller reductions in mortality among AYAs. Indeed, AYA mortality from motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) and other transport injuries, suicide, and homicide is rising in many countries.3 As a result, AYAs now have higher mortality rates than children 1 to 4 years old in high-, middle-, and some low-income countries.3 Economic development and the conquering of infectious diseases have resulted in improved child survival and created the “youth bulge” seen globally and in many LMIC. Yet, the same rapid social and economic change appears to be inimical to the health of AYAs.3

Globally, there are large numbers of avoidable deaths among AYAs from a range of causes, including intentional and unintentional injuries, maternal mortality, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Behaviors and attitudes acquired during adolescence and young adulthood are also critical determinants of future health. Five of the ten major risk factors for poor lifelong health identified in the Global Burden of Disease study largely originate during adolescence and young adulthood4: smoking, excess alcohol intake, obesity/overweight, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

Within the US, AYA health trends are similarly concerning. From 2000 to 2012, little progress has been made in improving most AYA outcomes, including those related to overall health (violence, mental health, health care access, substance use, obesity). Some indicators were significantly improved during this period, including unintentional injuries, assaults, cigarette smoking, and condom use. However, significant increases were reported in chlamydia/HIV infections, hearing loss, and ‘screen time’ for AYAs and for obesity rates among young adults.

Health concerns of young adults increasingly resemble those of adolescents (aged 10 to 19 years), given intersecting social trends toward longer engagement in formal education and delays in marriage and childbearing, leading to extended social transitions from adolescence into the adult years. As a result, the time span from puberty to adult social and financial independence in developed countries has increased from 6 years in the 1950s to over 15 years today. This is a global phenomenon, with similar trends in high-income countries and LMICs. Young adults have a spectrum of health behaviors that are similar to adolescents, and frequently higher prevalence of risky behaviors and worse outcomes.

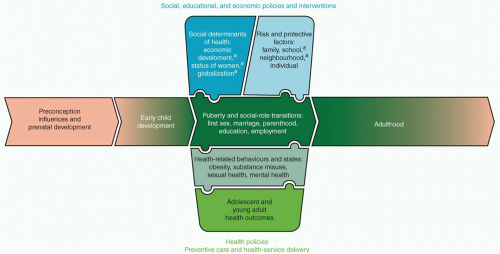

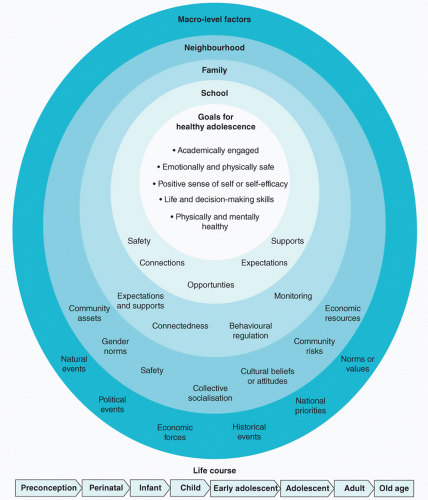

The first part of this chapter provides an integrated conceptual framework or perspective on social determinants, developmental influences, and life-course perspectives on the health of AYAs (Fig. 1.1).6 The second part of the chapter includes the US and global data to characterize variations in AYA health and health determinants. The third part of the chapter highlights a series of recommendations for health care providers and policy makers responsible for AYA health. Finally, the last part of this chapter includes supplementary information devoted to the morbidity and mortality of AYAs in the US.

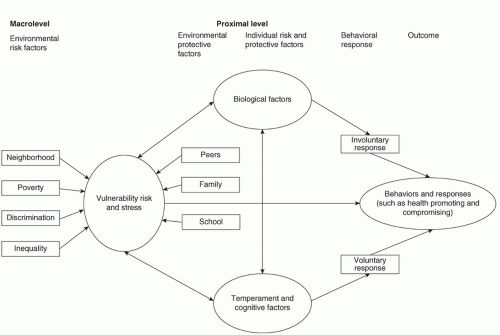

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health as ‘the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age’.7 Health services often focus on individual-level risks and behaviors (see Chapters 4 and 5), while the social determinants approach recognizes the health impact of social factors at family, peer group, school, community, national, and even global levels. As illustrated in the model shown in Figure 1.2, social determinants may have positive effects on resilience and health-enhancing behaviors as well as on the development or exposure to risky or harmful behaviors and situations.

The WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health7 differentiates fundamental structural factors (e.g., political, economic, education, and welfare systems) and more proximal factors that influence the “circumstances of daily life.” Proximal factors include social institutions (e.g., families, peers, and schools), food, housing, recreation, access to education and employment, and social and financial independence. The importance of various structural and proximal influences on AYA health is discussed below.

Structural Determinants of Health

Structural determinants of health include social policies and programs, economic policies, and politics that may create poor and

unequal living conditions, which affect the health of populations. These structural determinants operate within countries, but increasingly operate between countries as the effects of globalization. Structural determinants are significantly responsible for the poor health experienced by populations.

unequal living conditions, which affect the health of populations. These structural determinants operate within countries, but increasingly operate between countries as the effects of globalization. Structural determinants are significantly responsible for the poor health experienced by populations.

Income

National wealth and disparities in household income within countries are important determinants of many AYA health outcomes. With regard to national wealth, WHO data from 2011 show that:

Mortality rates for 15- to 19-year-olds varied from over 200/100,000 in some middle-income countries to under 50/100,000 in Japan, Singapore, and some European countries.8

Pregnancy rates for 15- to 19-year-old females are as high as 200/1,000 in the poorest nations, compared to less than 10/1,000 in developed nations such as Japan, Norway, Italy, and the Netherlands.

In contrast, injury and violence rates were unrelated to national income in the countries studied, and smoking rates among AYAs were higher in wealthier countries.8

In addition to the overall wealth of a country, inequality in per capita income within that country is also an important determinant of health outcome. Large differences in health outcomes are seen among countries that have similar per capita gross domestic product—both among low- and high-income countries (e-Fig. 1.1). Income inequality within a country appears to be of approximately equal importance to per capita national income with regards to rates of bullying, pregnancy, and mortality.8 In contrast, rates of smoking, violence, and injuries do not seem to be significantly related to country-level income inequality. High youth unemployment and rapid urbanization have been clearly linked to poor AYA health in some developing countries. Globally, rising national income is associated with improvements in health status, although rates of economic development vary considerably. Importantly, rising national wealth may have little effect on country-level income inequality.

Income inequality is substantially higher in the US compared to peer nations like those in Western Europe. In the US, around 40% of adolescents are categorized as living in or near poverty, with higher rates among Black and Hispanic populations.6 This inequality is reflected in greater disparities in AYA health such as rates of teen pregnancy.9

Education

Education has a powerful influence on health across the lifespan. Education is a marker of health literacy and practices. The wealth of nations and of individual families influences access to education; therefore, education is also an indicator of social and economic empowerment.

In 2008, the US life expectancy was 67.5 years for non-Hispanic White men who did not complete high school, compared to 80.4 years for those with a college degree. For women, the equivalent figures were 73.5 versus 83.9 years, respectively.10

Higher parental educational attainment is associated with improved child and adolescent health.

Among youth, connectedness to school, higher academic achievement, and school attendance are associated with lower rates of health-risk behaviors.

Globally, rising educational attainment is associated with improved health status, among nations and among families within nations. Education is commonly perceived as a gateway to social advancement by families and political leaders. Financial insecurity and family instability may reduce the ability of youth to continue education.

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of children attending elementary or primary school increased by 50 million worldwide. However, there were smaller increases in enrollment in secondary schools. Globally, there are still an estimated 71 million children of lower secondary age (11 to 14 years) who are out of school.11

In the least developed countries, one-quarter of AYA males (15- to 24-year-olds) and one-third of females are illiterate.11

Higher rates of attendance in secondary education are associated with lower rates of injuries, teen births, HIV prevalence, and overall mortality. The health effects are particularly marked among females, who are less likely to attend secondary school in some countries.

Migration

Another structural determinant of health is migration. Internal migration is found in movement from rural to urban areas, particularly in developing nations, which have sizeable rural populations. Many of these internal migrants are AYAs seeking employment. International AYAs is relatively uncommon before age 18, but then increases rapidly and peaks among young adults (e-Fig. 1.3).

Globally, around 175 million people (2.9% of the world’s population) live outside their country of origin. While immigrants are healthier on average than the general population in high-income countries (sometimes referred to as the “healthy immigrant effect”), migration may have adverse health consequences, particularly in regards to mental health.

War and Conflict

Conflict may influence health outcomes in many ways, from direct injuries to mental health sequelae and effects on food supply, housing, education, and employment opportunities. AYAs may be disproportionately affected by conflict—through direct involvement and by disruption of a formative period in the life course. Child soldiers are at particular risk. They are more likely to experience poor health outcomes than their peers, although education and family appear to confer a degree of protection.

Sex Inequality

Starting at puberty, sex is an increasingly important determinant of social roles, strongly influenced by cultural and religious factors. Health outcomes diverge throughout adolescence. Globally, females have a greater prevalence of poor self-reported health and psychosomatic complaints, while males have higher rates of injury and overweight/obesity. At the country level, sex inequality (as measured by the United Nations Sex Inequality Index) is an independent predictor of poor health outcomes for both sexes,8 suggesting that sex inequality may be harmful for young males as well as young females.

Employment

Globally, unemployment is more common among young adults. In the US, unemployment rates among young adults are consistently around twice as high as the overall adult rate. In 2013, the unemployment rate for Black young adults (aged 19 to 24 years) without a high school diploma was more than 50%, nearly twice that of the rate for White young adults.6

Proximal Social Factors

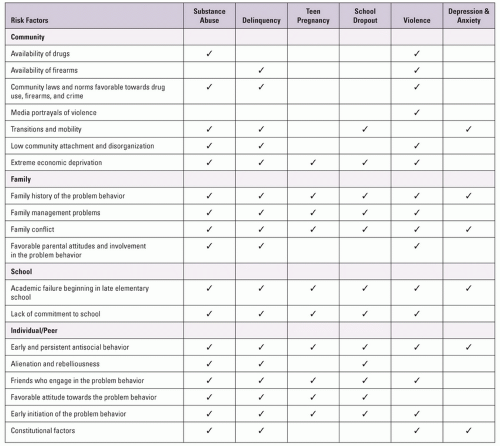

Other key determinants of health include social institutions (e.g., families, peers, and schools), food, housing, recreation, access to education and employment, and health behaviors that directly influence AYAs. These social factors have been shown to influence a wide variety of AYA health outcomes (Fig. 1.3).

Neighborhood

Living in a poor area is associated with a range of adverse adolescent outcomes, including lower educational attainment, poorer mental health, and higher rates of teenage pregnancy and youth violence. In addition to the structural effects of poverty described above, area-level deprivation is partly mediated through reduced social capital, which reduces resilience and opportunities available to AYAs.

School

Enjoyment and engagement with school (often described as school-connectedness) is associated with reduced substance use, better mental health, and a range of other health outcomes.12 Schools can also play an important role in improving health, both through public health interventions (e.g., alcohol programs) or through on-site health services, which have been shown to improve the quality of services young people receive and increase use of appropriate contraception.13

Families

While family influences are less dominant in adolescence and young adulthood than in early childhood, family connectedness and parental involvement remain important protective factors. Conversely, parental behaviors such as smoking, alcohol, and violence are all associated with higher rates of these behaviors among their children.

Peers

Peer approval is an increasingly important priority for most adolescents.12 Supportive peer relationships are associated with improved mental health outcomes. In addition, peer-led health interventions may offer an effective way to improve health behaviors. Peers can negatively impact health as well. Unhealthy behaviors by peers increase the risk of many adverse outcomes, including substance misuse, teenage pregnancy, and violent behavior. Peer interactions and popularity may contribute to high self-esteem.12 The health effects of high self-esteem are mixed. Individuals with high self-esteem may feel less pressure to emulate negative health behaviors of peers, or they may have increased exposure to negative health behaviors brought about by more frequent socializing with peers.

A life-course perspective is derived from an increasing body of evidence that health is influenced not only by current risk factors and social determinants, but also by factors from earlier in an individual’s life. Adolescence is a key period in lifelong health trajectories, with links both to prenatal and early childhood determinants and lifelong outcomes. For example:

Micronutrient deficiencies in utero are associated with schizophrenia in adolescence, and exposure to diethylstilbestrol in utero can cause vaginal cancer among AYA females.9

Interventions in early childhood have been shown to reduce teenage pregnancy and criminal activity among adolescents.

Teen smoking and sexual behaviors are associated with lung and genitourinary cancers in later life.9

Adolescence is a sensitive period for determining lifelong trajectories in health and well-being.8 While exploratory behavior is normal during adolescence and young adulthood, attitudes and habits acquired at this age can determine lifelong health risks. Patterns of behavior are not yet firmly established, leading to greater clustering of behaviors among AYAs relative to older adults. Holistic interventions during this time may improve a wide range of health and other outcomes.12 Determinants of behaviors are often complex, with interacting effects of community, family, school, area, and peers, in addition to individual factors8 (Fig. 1.4). As noted earlier, 5 of the top 10 risk factors for total burden of disease in adults are initiated or shaped in adolescence.12

Transitions in Adolescence and Young Adulthood

Both social determinants and life-course factors interact with the intrinsic biologic, psychological, and social transitions that take place during adolescence. Biologic transitions are influenced by nutritional and environmental factors, with the age of puberty falling in rich countries during the 19th and early 20th century. Subsequently, the timing has been fairly stable in rich countries since the 1960s.

The World Bank describes several key aspects of the social transition from childhood to adulthood.2

Dependent child to autonomous adult

Primary (elementary) to secondary/later education into the workforce

Transition into responsible and productive citizenship (growing up global)

Developmental markers such as age at first sex, marriage, and childbearing

Age at leaving education and entering workforce

Recipient of health care to responsibility for own health care

In the US during the 1960s, 77% of women and 67% of men completed their education, left home, achieved financial independence, married, and had children by the age of 30. By 2000, these five milestones had been reached by fewer than half of young women and only one in three young men.14 Young adults’ experience of this process varies widely between different countries and cultures. Within the US and globally, there have also been rapid changes in recent decades, influenced by diverse factors, including urbanization, mechanization, migration, industrialization, and the rise of new media. As a result of these changes, the gap between puberty and adult social and financial independence in developed countries has widened from 6 years in the 1950s to 15+ today.

Health Correlates of Transitions to Adulthood

Early parenthood is associated with health risks, due to lack of maturity, resources, and social support. Where early pregnancy violates community norms, these effects may be compounded by stigma and social isolation.

The US data suggest that delaying parenthood until age 34 is associated with improved future health of the mother, across a range of measures including self-reported health, prevalence of long-term conditions, and functional status.15

Earlier transitions to financial autonomy, living independently, or intimate relationships are associated with poorer adult outcomes. In addition to higher rates of anxiety and poor health, the likelihood of other adverse outcomes increase with earlier transitions, including substance misuse, criminal behavior, unemployment, divorce, and lower socioeconomic status (SES).

Slow transition (defined as little or no transition to adult roles by age 24) is also associated poor health outcomes, including increased criminal behavior and poor mental health.

Similarly, very early adolescent transition to independent self-management of chronic conditions such as diabetes has been linked to poorer disease control outcomes; however, very late transition to self-management is also associated with poor outcomes.

Global Overview

The world now has the largest generation of AYAs in history—1.2 billion aged 10 to 19, 1.8 billion aged 10 to 24, and approximately 2.0 billion AYAs aged 10 to 26 (17.3%, 26.3%, and 29.5% of the world population, respectively)1 (Fig. 1.5).

The countries with the largest adolescent populations are India (243 million), China (207 million), the US (44 million), and Indonesia and Pakistan (both with 41 million each).

Globally, 88% of adolescents live in LMICs. The proportion of the world’s adolescents living in urban areas was estimated at 50% in 2009, and is projected to increase to 70% by 2050, due to the increasing urbanization of developing nations.

In the last two decades, rapid improvements in childhood survival have produced so-called “youth bulges” (i.e., increases in youth as a percentage of the total population) in many countries, particularly rapidly developing countries. This can exacerbate youth unemployment, with too many workers for too few jobs.

The region with highest growth in its AYA population is sub-Saharan Africa, where numbers of adolescents are projected to overtake South Asia and East Asia and Pacific Regions by 2050 (e-Figs. 1.4 to 1.7).

Population Structure and Composition

Low replacement fertility and low rates of childhood mortality have produced a situation where some world regions currently have a greater number of AYAs than younger children. For every 10 children in the first decade of life in Europe,

there are 10.6 young people in the second decade of life and 13.6 in the third decade. This imbalance is even greater in some countries, such as Russia (16.4 in third decade for every 10 in first decade) and Japan (29.4 in third decade for every 10 in first decade).

Conversely, data from sub-Saharan Africa show continued high fertility and child mortality. For every 10 children in the first decade of life, there are 7.6 young people in the second decade and 6.0 in the third decade.

2012 US Census data show that there were 42.0 million adolescents aged 10 to 19 (13.4% of population) and 73.2 million AYAs aged 10 to 26 (23.3%).6,16 Compared to many other countries, the US has a more equal balance between first, second, and third decades. For every 10 children aged 0 to 9 years, there are 10.5 young people in the second decade and 10.6 in the third decade of life.1

The racial and ethnic composition of the AYA population in the US is changing rapidly. In 1980, 80% of AYAs aged 15 to 24 were White. In 2010, that figure was closer to 60%, and by 2040 it is projected to be under 50%.12 Non-White populations are now spread much more widely throughout the US rather than living in concentrated areas, which was common in the past.6

Global Mortality

Globally, an estimated 2.1 million deaths occurred among AYAs (10 to 24 years) in 2010.17

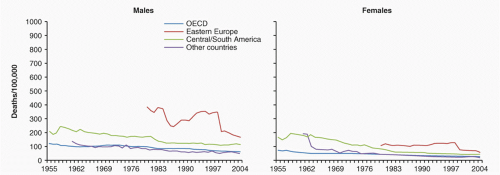

In a study of 50 low-, middle-, and high-income countries, the mortality rate decreased more rapidly among young children than AYAs from 1955 to 2004. Compared to a decrease

in mortality of 1.6% to 2.0% per year among children aged 1 to 9 years,17 mortality decreased by 1.4% to 2.0% per year among early adolescents (10 to 14 years), 1.2% to 1.7% per year in AYA females (15 to 24 years), and by 0.8% to 0.9% per year among AYA males (15 to 24 years) (Fig. 1.6). This is likely due to the health transition from infections to injuries and non-communicable diseases, which acts to shift disease burden from childhood to adolescence (e-Fig. 1.7).

Mortality from communicable diseases among AYAs decreased by 20 to 50 times over the last 50 years (i.e., to 2% to 5% of the baseline level). Communicable diseases are now relatively uncommon causes of death, even in low-income countries. Similarly, there are low overall rates of mortality from nutritional disorders in this age-group, although nutrition is still a significant concern in certain populations and in some countries.

Over the last 50 years, rates of maternal mortality (mortality related to pregnancies ending in birth, miscarriage, and abortion) decreased 12-fold in 21 high-income countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)*. Mortality decreased seven-fold in Central and South American countries and 40-fold in other countries. From 2000 to 2004, maternal mortality accounted for 6% of mortality among young women in Central and South American countries, but only 1% of deaths in other regions.

Despite declines in maternal mortality, adolescents are at higher risk of maternal death than older women; Latin American data show that death rates are 3 to 4 times higher among girls under 16 years old than women in their 20s.18

In addition, an estimated 1 to 4 million unsafe abortions are performed on adolescent girls in developing world.19 Unsafe abortion is estimated to be responsible for 13% of maternal deaths.

Mortality due to AYA injuries (10 to 24 years old) increased between the 1950s and the late 1970s for both sexes in OECD, Central and South American countries. Since 1978 to 1982, injuries have been the leading cause of death in AYA males in all regions, causing 70% to 75% of overall mortality. Injuries have been the leading cause of mortality for AYA females in OECD and eastern European countries (53% to 55%). Relative to other causes, injuries are an important but less common cause of mortality among women in Central and South America (35%).

MVCs and other transport injuries caused the greatest proportion of injury-related deaths in AYAs (10 to 24 years old) across most of the study period in all regions, with the exception of young men in Central and South American countries, where more injuries were due to violence.

Violence-related mortality increased in males and females aged 10 to 24 years across all regions during the study period, both in absolute rate and as a proportion of overall mortality. By 2000 to 2004, violence accounted for one-third of deaths in males within this age-group in Central and South American countries and two-fifths of deaths in eastern European countries. For females, and for males in other regions, violence accounted for 8% to 15% of mortality (e-Figs. 1.8 to 1.10ab).

There are an estimated 71,000 adolescent suicides every year, and the number who attempt suicide may be 40 times greater—almost 3 million. By 2000 to 2004, suicide accounted for 14% to 16% of deaths in young men in all regions except Central and South American countries (7%). Suicide was responsible for 11% of deaths in young women in OECD countries, 6% in Central and South American countries, 8% in eastern European countries, and 13% in other countries.

It is unknown how many injury deaths are due to domestic or sexual violence. However, these deaths are prevalent to varying degrees in all countries. Accurate figures are difficult to obtain, but domestic or sexual violence was reported by 65% of adolescent females aged 15 to 19 in Uganda.

The US data show that 4% of adolescent males and 11% of females reported that they had been forced to have sex20 (e-Fig. 1.11).

The US Mortality

The US data mirror global data in showing much smaller declines in age-specific mortality among AYAs than younger children. Between 1970 and 2010, young adult males have had the smallest declines of any age-group except for the very elderly21 (e-Fig. 1.12).

The US AYAs also have high rates of mortality compared to AYAs in comparable countries. In early adolescence (10 to 14 years), there is no difference in all-cause mortality between the US and comparable OECD countries. However, the US mortality among older AYAs (15 to 24 years) is significantly greater than peer countries, a finding that has been observed for many decades.9

The causes of high AYA mortality in the US compared to other rich countries are not well understood. However, high levels of mortality are associated with poor ranking across a wide range of health outcomes and risk factors.9

Cancer is the fourth highest cause of death among AYAs in the US, with the most common forms being lymphoma, leukemia, malignant melanoma, and central nervous system (CNS) cancers6 (e-Fig. 1.13).

The US Mortality Related to Injuries

Deaths in AYAs are dominated by unintentional injuries (particularly MVCs), homicide, and suicide. Together, these causes make up 47% of deaths among 10-year-olds, 81% among 18-year-olds, and equally high rates among young adults.

Although high-quality health care services can save the lives of individuals suffering injuries, effective strategies to reduce injury-related deaths require public health interventions. For example, death rates from MVCs fell by 38% between 1988 and 1992. The decline in MVCs has been attributed to implementation of the 1984 Uniform Drinking Age Act, which required states to raise the legal age for drinking alcohol to 21.12

The US is an outlier among developed countries on youth violence, with 3.4 million adolescents becoming victims of youth violence every year. The difference is particularly striking for firearms injuries. Among 26 high-income countries with populations exceeding 1 million, the US has more deaths among children and young people than the other 25 countries combined; rates of firearm-related death were nearly 12 times higher in the US than the other 25 countries.22

Suicide is the third most common cause of death among AYAs in the US, and 17% of young people report having considered suicide. There is evidence that suicide is influenced by different factors among AYAs than older groups. Relative to older groups, suicide among young veterans was more likely to be associated with relationship problems or misuse of alcohol and other substances. In contrast, suicide among older veterans was more strongly related to financial and medical concerns.

Similarly, suicide in younger groups is more commonly associated with impulsive and aggressive behaviors. The important role of impulsive behavior in AYA suicide reinforces the potential benefit of limiting access to firearms—around one in three firearms deaths among young people are self-inflicted.6

Disparities in the US Mortality

The US mortality among all races increases throughout adolescence and young adulthood, and large racial disparities persist in all age-groups. Black AYAs have the highest mortality rates (122.4 deaths/100,000 20 to 24 year olds; 19.1/100,000 10 to 14 year olds). AYAs of Asian/Pacific Islander descent have the lowest rates (36.9 and 7.8 deaths/100 000, respectively).6

Causes of mortality differ by racial groups and by sex in the US.

Among Black young adult males (aged 20 to 24 years), homicide is by far the most common cause of death (93.0/100,000/year—more than twice the rate of accidental deaths (37.8) and 6 times the rates of suicide (15.9)).

In contrast, among White young adult females (age 20 to 24 years), accidents are the dominant cause of death (20.0/100,000), followed by suicide (5.0) and malignant neoplasms (3.4). Homicides are the 4th leading cause (2.6/100,000).

There were 2.7 homicides and 1.3 suicides/100,000 among Black males aged 10 to 14 years in the US. For White males in this age-group, the figures were 0.7 and 1.8/100,000, respectively.

See e-Table 1.1.

Overview of Global and the US Morbidity

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) and Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) are measures of disease burden due to nonfatal health outcomes, or morbidity, and allow comparison of the relative disease burden associated with different risk factors and disease categories. As with mortality, adolescence and young adulthood is a time of transition from childhood patterns of morbidity—dominated at a global level by nutritional deficiencies and infections (diarrhea, pneumonia)—to adult patterns with high levels of mental health and musculoskeletal disorders4,23 (e-Fig. 1.14).

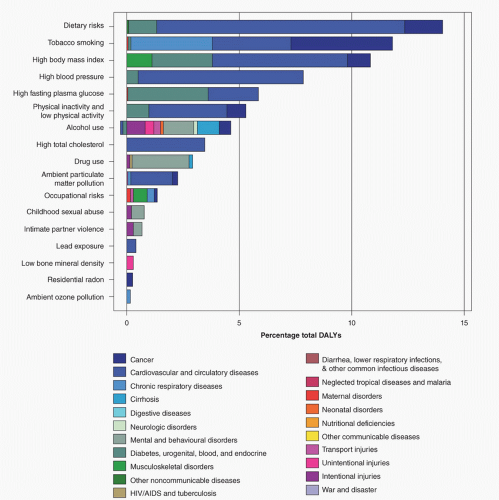

More than 10% of American young adults (aged 18 to 24 years) report disability due to a physical, mental, or emotional condition.6 Prevalence of many chronic conditions increases throughout adolescence and young adulthood. Some cause symptoms and influence quality of life in both the short and long term. For example, diabetes is diagnosed in about 1% of 18- to 25-year-olds and 2% of 26- to 34-year-olds (although others have diabetes which is undiagnosed). In contrast, rates of other conditions, such as hypertension, increase during adolescence and young adulthood; however, the effects may not be noticed until later in life.6 Figure 1.7 illustrates the relative contribution of leading risk factors to overall morbidity (expressed as DALYs) in the US population, broken down by the causes of increased morbidity in each case.

Mental Health

Approximately 20% of the world’s adolescents are affected by mental health or behavioral problems.

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders increases through adolescence in both males and females, peaking in late adolescence for males and the late 20s for females.

Seventy-five percent of lifetime cases of mental health disorders (excluding dementia) present by 24 years.

Among AYAs, mental and behavioral disorders account for an estimated 184 million DALYs lost worldwide.24 This measure combines years of life lost (YLLs) due to premature mortality and YLDs.

A nationally representative longitudinal survey tracked youth in the US from early adolescence until their 30s. Overall, they found that around 20% met criteria for a psychiatric disorder within any 3-month period. Over half of these (11% of the total) met the criteria for two or more disorders.25 By age 25, more than 60% had experienced a defined psychiatric disorder and an additional 20% reported psychiatric symptoms or impairment but did not meet formal diagnostic criteria25 (e-Fig. 1.15).

Sexual and Reproductive Health

AYAs are an important age-group for prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Globally, 41% of behaviorally acquired HIV infections occurred in 15- to 24-year-olds.26

The proportion of young women reporting that they had sex before the age of 15 is highest in Latin America and Caribbean (22% of women) and lowest in Asia.

In the US, around half of all STI diagnoses each year occur in 15- to 24-year-olds.

The US is an outlier among developed countries in teenage pregnancy, with rates 4 to 10 times higher than most Western European countries. Among 15- to 19-year-old girls, 8.4% become pregnant each year and 4% give birth (over 2,000 pregnancies and 1,100 deliveries/day).6

Forty-seven percent of high school students report having had sexual intercourse, increasing from 12% of 7th graders to more than 60% of 12th graders. Fifteen percent of high school students reported having more than 3 partners. Teen birth rates in the US have fallen by approximately 50% between 1991 and 2012. Much of the decline in the US teen pregnancy since 1991 is the result of improved contraceptive use—with some contribution from youth who choose to remain abstinent.27

Contraceptive methods are less likely to be effective among adolescents: 62% reported using a condom at last intercourse, of whom only two-thirds reported successful use.6

Unmarried women in their 20s account for more than 2,700 unplanned pregnancies/day. About 1,600 abortions/day are performed on women in their 20s (around half of all abortions).

About 20 million new STIs occur in the US/year, with about half among AYAs. Incidence of STIs is approximately equal in males and females.6

Each year, young adults account for 4.6 million cases of human papillomavirus, 1.9 million cases of trichomoniasis, and 1.5 million cases of chlamydia.

One in ten young adults in their 20s has genital herpes infection. The prevalence is estimated to be about one in three among Black, non-Hispanic young adults.

Around 50,000 people in the US are diagnosed with HIV every year. The highest incidence is among young adults aged 20 to 29 years.6

Health Behaviors

The 2010 Global Burden of Disease study identified the 10 risk factors which were responsible for the highest burden of disability and premature death. Of these, two (smoking and drinking alcohol) are largely initiated during adolescence, while others such as diet, overweight/obesity, and physical inactivity are strongly determined by behaviors and attitudes acquired during this period.28

Morbidity in the US is broadly similar, although smoking and alcohol are responsible for less death and disability than in many other high-income countries, while obesity and dietary factors are more important.

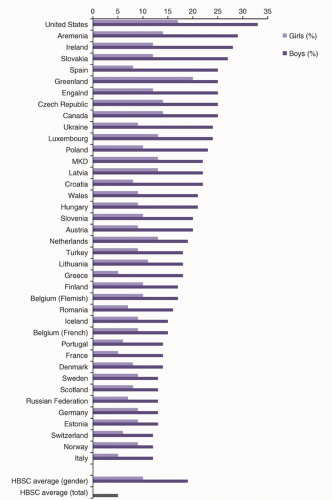

Prevalence of recommended physical activity for 15-year-olds is presented in Figure 1.8 for 43 high-income countries. e-Figures 1.16 to 1.18 present weekly smoking, weekly alcohol intake, and overweight/obesity among the same group.

The US has the highest overall rates of physical activity, with 33% of males and 17% of females reporting at least one hour of moderate/vigorous physical activity daily (see Fig. 1.8).

The US also has lower levels of smoking and alcohol use than many comparable countries (ranked fourth and fifth, respectively).

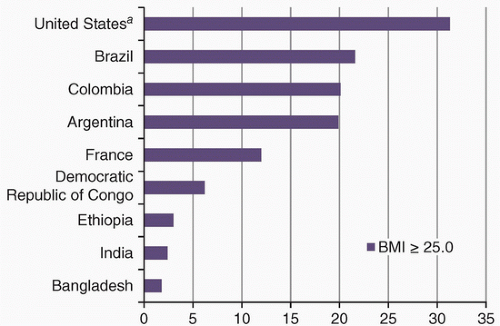

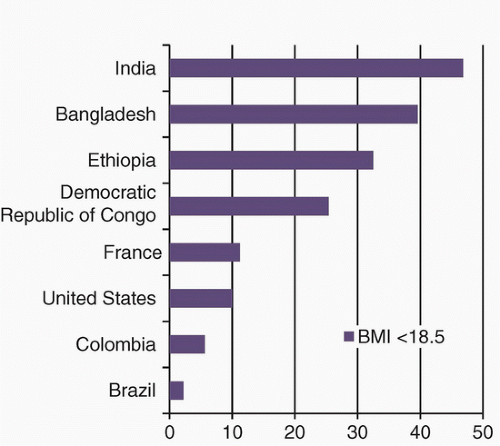

However, the US has the highest rates of overweight/obesity (34% of males, 27% of females). Cross-country comparisons of the proportion of 15- to 19-year-old girls who are overweight and underweight are presented in Figures 1.9 and 1.10.

Smoking

Approximately 80% of lifetime smokers initiate the habit as adolescents. Earlier age of initiation is linked to higher consumption in adulthood and greater mortality from smoking-related conditions.

The US data show that 22% of 8th graders report smoking, increasing to 46.2% of 12th graders.

Cigarette smoking in the US adolescents had declined steadily since the late 1990s, while the proportion using marijuana has plateaued during this time (e-Fig. 1.19).

Alcohol

AYAs drink on fewer occasions per month, but are more likely to binge drink than older adults (e-Fig. 1.20).

Obesity/Overweight

AYA obesity rates across OECD countries are high and have increased in recent decades.

Among young people in the US, obesity rates tripled between 1991 and 1999. Subsequently, the trajectory has slowed; currently, 31.9% of children and youth are ≥85th percentile for body mass index.6

80% of the US adolescents who are obese at the age of 18 will remain obese throughout their lives.6

In developed countries, dietary campaigns have focused on increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables. On average, young adults aged 18 to 25 years in the US eat about two portions of fruit or vegetables per day, compared with the recommended five.6

Compared to other high-income countries, AYAs in the US have relatively high levels of physical activity.29 Around 60% meet the recommended national guidelines.6

Some developing countries are now seeing a “double nutrition” burden, where obesity is increasing alongside undernutrition. More than 20% of females aged 15 to 19 years are overweight in several developing countries.19

In nine countries, more than half of all females aged 15 to 19 are anemic (India and eight countries in West/Central Africa). Underweight, anemia, and other nutritional deficiencies increase the risk of pregnancy and childbirth for both mother and baby19 (e-Fig. 1.21).

The US Trends in Risk Factors among AYAs

Worsening trends30:

Binge drinking

Marijuana use among 12- to 17-year-olds

Obesity rates

Higher rates of chlamydia, attendance at family planning clinics and STI clinics.

Improving trends:

Adolescents pregnancy (15- to 17-year-olds)

More adolescents have never had sex

Higher condom use among sexually active adolescents

Smoking

No change in rates:

Physical activity

Global Overview

There is a lack of reliable data regarding health care utilization among AYAs—either at a regional or country level. Many countries report health care statistics in very broad age ranges (e.g., 15- to 44-year-olds or 15- to 64-year-olds). In a recent overview of adolescent health indicators, health service use

was the only indicator for which no comparable country-level data were available.

The WHO has advocated for universal access to health care among all age-groups and in all countries. In addition to financial barriers, many of the world’s AYAs do not receive adequate health care for a variety of reasons, including lack of awareness/engagement with their health, concerns about the confidentiality or quality of the service offered, and practical and transport problems.

Unmet health care needs in adolescence is associated with a range of poor health outcomes, including higher prevalence of physical and mental health symptoms, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

In rich countries with universal access to health care, adolescence is a time of increasing health care utilization. This is especially true for females whose health service use is greater among adolescents than children aged 1 to 9 years.31

The US Overview

In the US, average health care expenditures for both adolescents (12 to 17 years) and young adults (18- to 25-year-olds) are around $2,000/year. Among young adults, 17% of health care expenditure was out of pocket; a similar proportion of expenditure was out of pocket among adolescents (12 to 17 years) and older adults (≥26 years).6

In 2010, AYAs (15- to 24-year-olds) accounted for 8.1% of all office visits, an average of 1.9 visits/person.

In 2007, AYAs (15- to 24-year-olds) accounted for 16.3% of all emergency department (ED) visits, an average of 0.46 visits/person.

Among the US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years, the most common reasons for attending an ED were superficial injuries, sprains/strains, upper respiratory infections, asthma, and abdominal pain. Among those who were admitted from the ED, the most common categories were asthma, appendicitis, mood disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and behavioral disorders, and fluid/electrolyte disorders.

For those aged 15 to 17 years, the reasons were similar, although there were fewer visits/admissions for asthma, and higher rates of mood disorders and injuries.

See e-Figs. 1.22 and 1.23.

Insurance Coverage and Access to Health Care

The US is unique among developed countries in having significant numbers of AYAs with no or inadequate health care insurance.16

AYA health care usage is influenced by insurance coverage. For example, young adults (18 to 24 years) are less likely to have health insurance and are more likely to access care at an ED, compared to adolescents (12 to 17 years).32

The US survey data show a gradual reduction in the number of youth under 18 years old with no usual source of health care, from 7.7% in 1993 to 1994 to 4.7% in 2010 to 2011. However, the proportion is much higher among some subgroups (e.g., 7.9% of Hispanics, 12.8% who have been uninsured for up to 12 months, and 36.2% of those who have been uninsured for over 12 months).33

The number of uninsured young adults decreased following passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), 2010. Under these reforms, young adults are entitled to be covered by their parents’ insurance until age 26 years. Young adults are an important target group for the health insurance exchanges. Despite the ACA, young adults remain the most likely population to be uninsured in the US with over 20% of 19- to 26-year-olds lacking coverage. Among insured young adults, many have catastrophic health insurance coverage, which may not provide adequate access to care (e-Fig. 1.24).

Prior to these health care reforms, young adults reported the lowest rates of insurance coverage of any age-group. This was due in part to the trend away from employer-provided insurance, which covered 31% of college graduates aged 21 to 24 in 2011, compared to 60% in 1989. Similar trends are seen among high school graduates aged 17 to 20, whose coverage dropped from 24% to 7% during this period.6

Disparities in health care utilization reflect both differential access and health care need. Consistent with the high mortality rates from violence among young Black males, 2011 hospital data recorded 150,000 violent injuries among Black AYA males (aged 15 to 34), representing about 1 of every 41 males in this demographic.6

Mental Health Services Utilization by AYAs in the US

Only 1 in 4 young adults with a psychiatric disorder are receiving mental health services.6

Poor communication and coordination between pediatric and adult mental health systems hinder continuity and care quality.6

When attending mental health services, AYAs (aged 16 to 30 years) are more likely to drop out of treatment than older adults.6

Defining and Improving the Quality of AYA Health and Health Promotion Services.

Health Services

Adolescence and young adulthood are often perceived as healthy times of life. Services for AYAs are often a low priority and do not meet the specific needs of this population.

Most countries have few dedicated AYA services, although such services have been shown to improve quality of care.

There is an increasing recognition and evidence base regarding the distinct health care needs and priorities of AYAs.16 In many cases, these needs are similar for AYAs across the world.34 For example, confidentiality and communications skills of health care providers are important in both the US and low-income countries, although distinct cultural factors are present for each country.

Targeted age-appropriate health services can improve health outcomes in chronic conditions.35

For many conditions, outcomes worsen in early adulthood as independent management coincides with transition to adult services and geographic movement for study/work.36 Self-efficacy intervention improves quality of life among adolescents with chronic conditions.

Since the publication of the 2002 WHO Agenda for Change, there have been policy efforts toward age-appropriate, adolescent friendly health care in every WHO region.19

Several quality frameworks and tools have been published to support professionals in improving the quality of service for AYAs. They include an Australian framework for AYA inpatient care,37 European primary care and inpatient tools, which have been endorsed by the WHO, and the US models like those for AYA mental health services and cancer care and follow-up.6

Health Promotion

The US data show that provision of school-based health centers is associated with better experience of adolescent care and more healthy behaviors (e.g., use of appropriate contraception).

Integrating the literature on social determinants of health, life-course perspectives, and evolving transition processes may inform more effective, evidence-based public health interventions in the future. For example, peer-led smoking interventions may be more likely to engage young people than awareness campaigns or interventions delivered purely by professionals.

Similarly, programs that foster a positive and healthy self-identity may be more effective at reducing risk behaviors among AYAs than traditional interventions. Evaluation of programs that use fear to reduce risk behaviors (e.g., the anticrime Scared Straight program) or intensive professional/group support (Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study) has shown that outcomes among participants were sometimes worse than among controls.38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree