Head and Neck Cancer in Developing Countries

Johan Fagan

Clare Stannard

INTRODUCTION

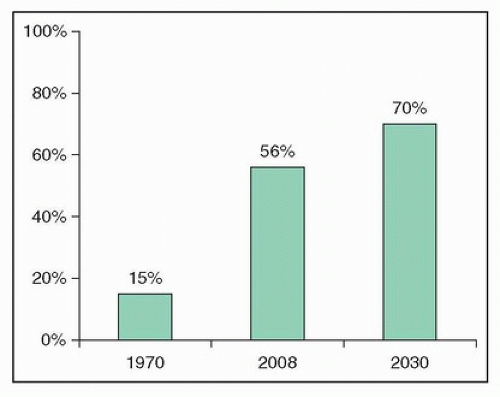

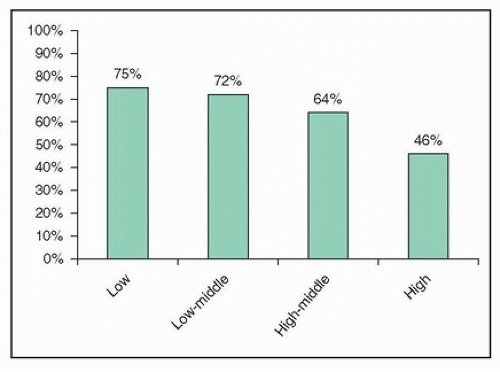

Cancer in developing countries is a public health crisis. Developing countries constitute the majority of the world’s landmass (Fig. 25.1) and are home to more than 50% of its people. Farmer et al.1 reported in 2010 that developing countries accounted for more than 50% of newly diagnosed cancers and projected that this would increase to 70% by 2030 (Fig. 25.2); this increase can be attributed to population growth, reduced mortality from infectious diseases, and an aging society. The same authors report a wide disparity in cancer-related case mortality, which is aligned with income levels of countries, ranging from 75% in low-income countries to 46% in high-income countries (Fig. 25.3).1 Even though developing countries account for 67% of cancer-related deaths, they account for only 5% of cancer-related spending.1 For all the aforesaid reasons, a discussion about head and neck cancer would be incomplete were it not to include a developing world perspective. It is also apparent that, in order to improve head and neck cancer outcomes globally, it is essential that innovation, expertise, resources, teaching, and research also be directed at addressing cancer in the developing world.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

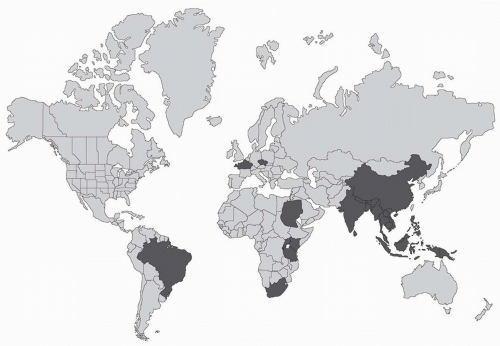

The developing world is undergoing rapid economic growth; this is accompanied by lifestyle changes such as increased rates of smoking and alcohol consumption. These changes coupled with increased longevity are associated with global changes in the epidemiology of squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Two-thirds of oral and pharyngeal cancers (excluding nasopharynx) occur in developing countries.2 Figure 25.4 illustrates the significant geographical variation that exists for the incidence of oral cancer; it is the most common cancer in males in high-risk areas such as Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh and accounts for up to 25% of all new cancers.2 The principal causes of oral cancer are tobacco (smoked or chewed) and betel quid.2 Buccal cancer is common in Asia due to its association with betel quid and tobacco chewing; 40% of oral cancers in Sri Lanka are buccal carcinomas.2

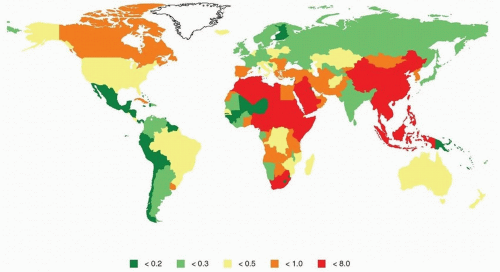

Cancer of the nasopharynx is also principally a developing world problem (Fig. 25.5).3 It is associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in China, Southeast Asia, northern Africa, and the Inuits of Alaska4 where nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma are more common. Human papillomavirus (HPV) may be an etiologic factor in the EBV-negative Caucasian population.5

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is associated with malignancies of the head and neck. The prevalence of HIV is highest in developing countries; two-thirds of HIV-positive people live in sub-Saharan Africa and the prevalence of HIV in South Africa is 18%.6 Engsing et al.7 reported in a Danish study that even though HIV status was associated with a higher risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, it appeared to be a marker of family-related risk factors associated with head and neck carcinoma rather than immunosuppression or HIV infection causing carcinoma per se. HIV is associated with Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin (and Hodgkin) lymphoma. In a study of a cancer population, those with squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva were 10 times more likely to be HIV positive than those with other cancers.8

Although the association of HPV infection with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx is now well established, few studies exist of HPV and cancer of the oropharynx in developing countries.

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS WHEN TREATING HEAD AND NECK CANCER IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

It is generally not possible to simply apply treatment protocols suited to developed world centers of excellence to head and neck patients in a developing world setting. Important considerations when making treatment decisions are next discussed.

Advanced Cancer

Patients in developing countries are more likely to present with advanced cancer9,10; consequently, treatment is primarily palliative.11 Onyango9 reported that 58% of laryngeal cancer patients required emergency tracheostomy in Kenya. Even South Africa, a middle-income country, 52% of patients undergoing total laryngectomy in Cape Town required emergency tracheostomy.12 Late presentation may be attributed to ignorance, poverty, poor access to specialized health services, and patients turning initially to traditional healers and traditional remedies.

The adverse consequences of delayed presentation are compounded by long waiting lists for surgery and irradiation. Frequently, patients become inoperable while awaiting surgery or radiation therapy; this complicates initial patient selection and treatment planning. In a study of patients awaiting treatment for head and neck cancer, Jensen et al.13 reported that 1 month’s delay was associated with 62% increase in tumor size and 20% in new nodal metastases and that cancers were upstaged (TNM) in 16% of patients studied; mean tumor volume doubling time was 3 months. Some institutions administer “holding chemotherapy” (methotrexate or platinum-based drugs) to slow tumor progression while patients await

definitive treatment, even though there is no published evidence that this practice improves the outcome.

definitive treatment, even though there is no published evidence that this practice improves the outcome.

HIV Status

When managing HIV-positive patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, especially when resources are limited, an oncology team may need to consider the following:

Is radiotherapy in HIV-positive patients accompanied by the potential for increased mucosal and cutaneous toxicity? Although many reports exist of radiotherapy-induced skin and mucosal toxicity with Kaposi sarcoma, the few reports of toxicity with other head and neck malignancies indicate good tolerance to radiation ± chemotherapy.14,15,16

Should antiretroviral therapy be initiated in immunocompromised patients to boost CD4 counts prior to initiating (chemo)radiation therapy? Radiation therapy can suppress CD4 counts; therefore, even though it may seem reasonable to commence antiretroviral therapy to boost depressed CD4 counts prior to initiating radiation, there are no controlled studies to address this. Although interactions between antiretroviral therapy and radiation have not been well documented in the literature, there is a theoretical concern about the additive myelosuppressive effects of certain antiretroviral agents and myelosuppressive chemotherapeutic agents used with head and neck cancers, for example, platinum alkylators such as cisplatin and carboplatin.16

What is the anticipated life expectancy of an HIV-positive patient? Adults that commence antiretroviral therapy before CD4 counts drop to <200 cells/mm3 have about 80% of normal life expectancy; even the most severely ill

HIV patients treated with antiretroviral therapy have at least an 80% chance of surviving 2 years.17

Figure 25.4. Countries with high incidence and mortality from oral cancer. (From Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309-316.)

Figure 25.5. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Estimated age-standardized incidence rate/100,000; GLOBOCAN 2008 (IARC). (From GLOBOCAN 2008: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2013.)

How do CD4 count and HIV status affect surgery? Even major surgery does not depress CD4 counts,18 and HIV status per se does not affect the incidence of early surgical complications.19 A low CD4 count (<100 cells/mm3) has however been reported to be a predictor of postoperative sepsis.20,21 Instituting antiretroviral therapy prior to surgery has the benefits of reducing viral load (viral exposure to the surgical team) and increases patients’ CD4 counts.

In view of the above, there is inadequate evidence to modify treatment in generally healthy HIV-positive patients (CD4 count >350 cells/mm3) with head and neck cancer.16 There is also little reason to routinely determine the HIV status of an otherwise healthy-looking head and neck cancer patient from an oncologic perspective alone; only when HIV infection causes general ill health and immunosuppression may HIV status preclude patients from undergoing major surgery or chemoradiation.

Patient Prioritization

Deciding who or who not to treat when the burden of head and neck cancer exceeds available treatment resources is perhaps the most difficult task oncologists and surgeons in developing countries have to face. It involves ethical and practical considerations such as tumor stage, prognosis, palliation versus cure, comorbidities, nutritional status, age, socioeconomic status, social support structure, distance from the closest treatment center, likelihood of regular follow-up, parental status, employment, and the ethical dilemma of whether to deny publicly funded treatment to patients originating from a foreign country without adequate treatment facilities. As access to surgery and radiotherapy are the principal bottlenecks in many developing countries, it is reasonable to prioritize patients with the most curable (early-stage) malignancies, especially when adjuvant radiation is not available or will be significantly delayed following resection of advanced malignancies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree